INVISIBLE WOMEN: a CALL to ACTION a Report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Part I, Vol. 145, Extra No. 6

EXTRA Vol. 145, No. 6 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 145, no 6 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, FRIDAY, MAY 20, 2011 OTTAWA, LE VENDREDI 20 MAI 2011 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 41st general election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 41e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Saskatoon—Humboldt Brad Trost Saskatoon—Humboldt Brad Trost Tobique—Mactaquac Mike Allen Tobique—Mactaquac Mike Allen Pickering—Scarborough East Corneliu Chisu Pickering—Scarborough-Est Corneliu Chisu Don Valley East Joe Daniel Don Valley-Est Joe Daniel Brampton West Kyle Seeback Brampton-Ouest Kyle Seeback Eglinton—Lawrence Joe Oliver Eglinton—Lawrence Joe Oliver Fundy Royal Rob Moore Fundy Royal Rob Moore New Brunswick Southwest John Williamson Nouveau-Brunswick-Sud-Ouest John Williamson Québec Annick Papillon Québec Annick Papillon Cypress Hills—Grasslands David Anderson Cypress Hills—Grasslands David Anderson West Vancouver—Sunshine West Vancouver—Sunshine Coast—Sea to Sky Country John Dunbar Weston Coast—Sea to Sky Country John Dunbar Weston Regina—Qu’Appelle Andrew Scheer Regina—Qu’Appelle Andrew Scheer Prince Albert Randy Hoback Prince Albert Randy Hoback Algoma—Manitoulin— Algoma—Manitoulin— Kapuskasing Carol Hughes Kapuskasing Carol Hughes West Nova Greg Kerr Nova-Ouest Greg Kerr Dauphin—Swan River—Marquette Robert Sopuck Dauphin—Swan River—Marquette Robert Sopuck Crowfoot Kevin A. -

Download Download

November 27, 2008 Vol. 44 No. 33 The University of Western Ontario’s newspaper of record www.westernnews.ca PM 41195534 MARATHON MAN CANADIAN LANDSCAPE VANIER CUP Brian Groot ran five marathons in six Explore a landmark ‘word- The football Mustangs have weeks this fall in part to see if he could painting’ that captures the feel a lot to look forward to after surprise himself. That, and raise money of November in Canada. coming within one game of the for diabetes research. national title. Page 8 Page 6 Page 9 ‘Why isn’t Photoshopping for change recycling working?’ Trash audits are uncovering large volumes of recyclables B Y HEAT H ER TRAVIS he lifecycle of a plastic bottle or fine paper should Tcarry it to a blue recycling bin, however at the University of Western Ontario many of these items are getting tossed in the trash. To keep up with the problem, the Physical Plant department is playing the role of recycling watchdog. A challenge has been issued for students, faculty and staff to think twice before discarding waste – especially if it can be reused or recycled. Since Septem- ber, Physical Plant has conducted two waste audits of non-residence buildings on campus. In October, about 21 per cent of the sampled garbage was recy- clable and about 19 per cent in September. In these surveys of 10 Submitted photo buildings, Middlesex College and What would it take to get young people to vote? On the heels of a poor youth turnout for last month’s federal election, computer science students the Medical Science building had were asked to combine technology and creativity to create a marketing campaign to promote voting. -

Myth Making, Juridification, and Parasitical Discourse: a Barthesian Semiotic Demystification of Canadian Political Discourse on Marijuana

MYTH MAKING, JURIDIFICATION, AND PARASITICAL DISCOURSE: A BARTHESIAN SEMIOTIC DEMYSTIFICATION OF CANADIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE ON MARIJUANA DANIEL PIERRE-CHARLES CRÉPAULT Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Daniel Pierre-Charles Crépault, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 ABSTRACT The legalization of marijuana in Canada represents a significant change in the course of Canadian drug policy. Using a semiotic approach based on the work of Roland Barthes, this dissertation explores marijuana’s signification within the House of Commons and Senate debates between 1891 and 2018. When examined through this conceptual lens, the ongoing parliamentary debates about marijuana over the last 127 years are revealed to be rife with what Barthes referred to as myths, ideas that have become so familiar that they cease to be recognized as constructions and appear innocent and natural. Exploring one such myth—the necessity of asserting “paternal power” over individuals deemed incapable of rational calculation—this dissertation demonstrates that the processes of political debate and law-making are also a complex “politics of signification” in which myths are continually being invoked, (re)produced, and (re)transmitted. The evolution of this myth is traced to the contemporary era and it is shown that recent attempts to criminalize, decriminalize, and legalize marijuana are indices of a process of juridification that is entrenching legal regulation into increasingly new areas of Canadian life in order to assert greater control over the consumption of marijuana and, importantly, over the risks that this activity has been semiologically associated with. -

COUNCIL Agenda

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of January 24, 2018 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the November 22, 2017 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Set the budget parameters for the upcoming fiscal year b) Bequest from the estate of Dorothy May Hayward c) Appointment of Architectural firm to design the new residence d) Approval of the Sketch Design Offer of Services for the new residence e) Development Committee f) Call for Honorary Degree Nominations 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Reports from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Spiritual Advisor vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL MINUTES For the Meeting of November 22, 2017 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College Present: D. Watt, G. Bak, P. Cloutier (Chair), J. McConnell, H. Richardson, J. Ripley, J. Markstrom, I. Froese, P. Brass, C. Trott, C. Loewen, J. James, S. Peters (Secretary) Regrets: D. Phillips, B. Pope, A. Braid, E. Jones, E. Alexandrin 1. Opening Prayer C. Trott opened the meeting with prayer. 2. Approval of the Agenda MOTION: That the agenda be approved as distributed. D. Watt / J. McConnell CARRIED 3. Approval of the September 27, 2017 Minutes MOTION: That the minutes of the meeting of September 27, 2017 be approved as distributed. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

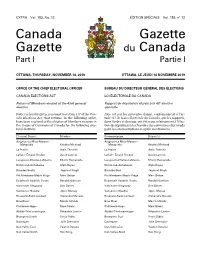

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Debates of the House of Commons

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION House of Commons Debates Official Report (Hansard) Volume 150 No. 089 Tuesday, April 27, 2021 Speaker: The Honourable Anthony Rota CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 6213 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, April 27, 2021 The House met at 10 a.m. Pursuant to Standing Order 109, the committee requests that the government table a comprehensive response to this report. Prayer ● (1005) INDUSTRY, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS ● (1000) Hon. Pierre Poilievre (Carleton, CPC) moved that the fifth re‐ port of the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technolo‐ [English] gy, presented to the House on Friday, March 26, 2021, be concurred PORT OF MONTREAL OPERATIONS ACT, 2021 in. Hon. Filomena Tassi (Minister of Labour, Lib.) moved for leave to introduce Bill C-29, An Act to provide for the resumption He said: Mr. Speaker, today I will be sharing my time with the and continuation of operations at the Port of Montreal. member for Red Deer—Mountain View, or, as I like to call him, the (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) “Earl of Red Deer”. He deserves all of the credit for his work on this particular bill. He is the longest-serving Conservative member * * * on the industry committee. I would like to thank him for his incred‐ [Translation] ible and tireless work at that committee and for his contributions to COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE this important study and the report that we are debating on that study today. JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS Ms. Iqra Khalid (Mississauga—Erin Mills, Lib.): Mr. -

Outspoken Liberal MP Wayne Long Could Face Contested Nomination

THIRTIETH YEAR, NO. 1617 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER WEDNESDAY, MARCH 27, 2019 $5.00 Senate to ditch Phoenix in January p. 5 The Kenney campaign con and the new meaning of narrative: PCO clerk Budget puts off transition: what pharmacare reform, but Lisa Van Dusen feds say it takes the fi rst p. 9 to expect p. 6 ‘concrete steps’ p. 7 News Politics News Parliamentary travel Tories block some House Outspoken Liberal MP committee travel, want to stay in Ottawa as election looms Wayne Long could face Half of all committee trips BY NEIL MOSS that have had their travel he Conservatives are blocking budgets approved by THouse committee travel, say contested nomination some Liberal committee chairs, the Liaison Committee’s but Tory whip Mark Strahl sug- gested it’s only some trips. Budgets Subcommittee A number of committees have Liberal MP had travel budgets approved by Wayne Long since November have the Liaison Committee’s Subcom- has earned a not been granted travel mittee on Committee Budgets, reputation as an but have not made it to the next outspoken MP, authority by the House of step to get travel authority from something two New Brunswick Commons. Continued on page 4 political scientists say should help News him on the Politics campaign trail in a traditionally Conservative Ethics Committee defeats riding. The Hill Times photograph by opposition parties’ motion to Andrew Meade probe SNC-Lavalin aff air Liberal MP Nathaniel BY ABBAS RANA Erskine-Smith described week after the House Justice the opposition parties’ ACommittee shut down its He missed a BY SAMANTHA WRIGHT ALLEN The MP for Saint John- probe of the SNC-Lavalin affair, Rothesay, N.B., is one of about 20 motion as ‘premature,’ the House Ethics Committee also deadline to meet utspoken Liberal MP Wayne Liberal MPs who have yet to be as the Justice Committee defeated an opposition motion Long could face a fi ght for nominated. -

We Put This Together for You and We're Sending It to You Early

Exclusively for subscribers of The Hill Times We put this together for you and we’re sending it to you early. 1. Certified election 2019 results in all 338 ridings, top four candidates 2. The 147 safest seats in the country 3. The 47 most vulnerable seats in the country 4. The 60 seats that flipped in 2019 Source: Elections Canada and complied by The Hill Times’ Samantha Wright Allen THE HILL TIMES | MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2019 13 Election 2019 List Certified 2019 federal election results 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 Votes Votes% Votes Votes% Votes Votes% ALBERTA Edmonton Riverbend, CPC held BRITISH COLUMBIA Banff-Airdrie, CPC held Matt Jeneroux, CPC 35,126 57.4% Tariq Chaudary, LPC 14,038 23% Abbotsford, CPC held Blake Richards, CPC 55,504 71.1% Ed Fast, CPC 25,162 51.40% Audrey Redman, NDP 9,332 15.3% Gwyneth Midgley, LPC 8,425 10.8% Seamus Heffernan, LPC 10,560 21.60% Valerie Kennedy, GRN 1,797 2.9% Anne Wilson, NDP 8,185 10.5% Madeleine Sauvé, NDP 8,257 16.90% Austin Mullins, GRN 3,315 4.2% Stephen Fowler, GRN 3,702 7.60% Edmonton Strathcona, NDP held Battle River-Crowfoot, CPC held Heather McPherson, NDP 26,823 47.3% Burnaby North-Seymour, LPC held Sam Lilly, CPC 21,035 37.1% Damien Kurek, CPC 53,309 85.5% Terry Beech, LPC 17,770 35.50% Eleanor Olszewski, LPC 6,592 11.6% Natasha Fryzuk, NDP 3,185 5.1% Svend Robinson, NDP 16,185 32.30% Michael Kalmanovitch, GRN 1,152 2% Dianne Clarke, LPC 2,557 4.1% Heather Leung, CPC 9,734 19.40% Geordie Nelson, GRN 1,689 2.7% Amita Kuttner, GRN 4,801 9.60% Edmonton West, CPC held Bow River, CPC held -

Rcmp-Rrcmp-1942-Eng.Pdf

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1942 TO BE PURCHASED DIRECTLY FROM THE KING'S PRINTER DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC PRINTING AND STATIONERY, OTTAWA, ONTARIO, CANADA OTTAWA EDMOND CLOliTIER PR INTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1942 Price, 50 cents DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF' THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1942 - Copyright of this document does not belong to the Crown. -

Rcmp-Rrcmp-1965-Eng.Pdf

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. CANADA Report of the ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 1965 CANADA Report of the ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 1965 99876-1 , ROGER DUHAMEL, F.Ft.S.C. Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa, 1967 Cat. -

Core 1..40 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

Standing Committee on the Status of Women FEWO Ï NUMBER 133 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Thursday, February 28, 2019 Chair Mrs. Karen Vecchio 1 Standing Committee on the Status of Women Thursday, February 28, 2019 probably already familiar with. According to Quebec's statistics agency, the Institut de la statistique du Québec, the province is home Ï (0850) to just over 1.5 million seniors, 54% being women and 46% being [English] men. National statistics confirm that more women than men make up The Vice-Chair (Ms. Irene Mathyssen (London—Fanshawe, the over 65 population as well as the over 85 population. NDP)): Good morning and welcome to the 133rd meeting of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women. This is a televised This demographic shift has long been known. In Quebec, 30 out meeting. of 100 people are under the age of 25 and 34 out of 100 are over 65. Today we will continue our study of the challenges faced by Despite some initial efforts, governments and agencies need to move senior women with a focus on the factors contributing to their quickly to implement comprehensive measures to support seniors as poverty and vulnerability. agents of change in society. After all, seniors have a long list of accomplishments. They still have much to say and contribute to For this meeting, we are very pleased to welcome, from society and can indeed be agents of change. l'Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraitées, Luce Bernier, president, and Geneviève I will say that, in Canada and Quebec, the concept of gender Tremblay-Racette, director.