Oculogyric Crises: Etiology, Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

Eye Movement Disorders and Neurological Symptoms in Late-Onset Inborn Errors of Metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A

University of Groningen Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A. J.; Lange, Fiete; Wolffenbuttel, Bruce H. R.; Rufa, Alessandra; Zee, David S.; de Koning, Tom J. Published in: Movement Disorders DOI: 10.1002/mds.27484 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Koens, L. H., Tijssen, M. A. J., Lange, F., Wolffenbuttel, B. H. R., Rufa, A., Zee, D. S., & de Koning, T. J. (2018). Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism. Movement Disorders, 33(12), 1844-1856. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.27484 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

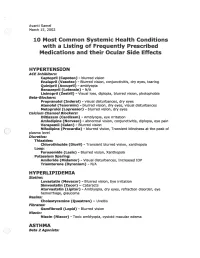

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes

STATE OF THE ART Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes Melissa W. Ko, MD, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, and Steven L. Galetta, MD Abstract: Paraneoplastic syndromes with neuro- PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR ophthalmologic manifestations may involve the cen DEGENERATION tral nervous system, cranial nerves, neuromuscular Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is junction, optic nerve, uvea, or retina. Most of these a syndrome of subacute severe pancerebellar dysfunction disorders are related to immunologic mechanisms (Table 1). Initially, patients present with gait instability. presumably triggered by the neoplastic expression of Over several days to weeks, they develop truncal and limb neuronal proteins. Accurate recognition is essential to ataxia, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The cerebellar disease appropriate management. eventually stabilizes but leaves patients incapacitated. PCD is most commonly associated with cancers of (/Neuro-Ophthalmol 2008;28:58-68) the lung, ovary, and breast and with Hodgkin disease (7). Ocular motor manifestations include nystagmus, ocular dysmetria, saccadic pursuit, saccadic intrusions and he term "paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome" (PNS) oscillations, and skew deviation (8). Over the last 30 refers to dysfunction of the nervous system caused by T years, at least nine anti-neuronal antibodies have been a benign or malignant tumor via mechanisms other than associated with PCD. However, only about 50% of patients metastasis, coagulopathy, infection, or treatment side with suspected PCD test positive for anti-neuronal anti effects (1). Whereas reports of possible paraneoplastic bodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (9). Anti-Yo neuropathies extend back to the 19th century, cerebellar syndromes associated with cancer were first described by and anti-Tr are the autoantibodies most commonly Brouwerin 1919 (2). -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Psychotropic Drugs and Ocular Side Effects Psikotropik İlaçlar Ve Oküler Yan Etkileri

DOI: 10.4274/tjo.43.67944 Review / Derleme Psychotropic Drugs and Ocular Side Effects Psikotropik İlaçlar ve Oküler Yan Etkileri İpek Sönmez, Ümit Aykan* Near East University, Department of Psychiatry, Nicosia, TRNC, MD *Near East University, Department of Ophthalmology, Nicosia, TRNC Sum mary Nowadays the number of patients using the types of drugs in question here has significantly increased. A study carried out in relation with the long term use of psychotropic drugs shows that the consumption of this group of drugs has substantially increased in terms of variety and quantity. This compilation is arranged in accordance with the ocular complications of psychotropic drugs in long term treatment profile of numerous patients to the results of related literature review. If the doctor and the patients are informed about the eye problems related to the use of psychotropic drugs, potential ocular complications can be easily prevented, supervised and controlled and can even be reversed. (Turk J Ophthalmol 2013; 43: 270-7) Key Words: Psychotropic drugs, ocular, side effects, adverse effects Özet Günümüzde kronik ilaç kullanan hasta sayısı önemli derecede artmıştır. Uzun süreli psikotrop ilaç kullanımı açısından yapılan bir çalışma, hem çeşitlilik hem de miktar açısından bu grup ilaç tüketiminin önemli derecede arttığını göstermektedir. Bu derleme günümüzde çok sayıda hastanın uzun süreli tedavi profilinde yer alan psikotrop ilaçların oküler komplikasyonlarına ilişkin literatür taraması sonucu hazırlanmıştır. Hekim ve hastalar psikotrop ilaç kullanımına bağlı göz problemleri açısından bilgili oldukları takdirde potansiyel oküler komplikasyonlar kolayca önlenebilir, gözlem ve kontrol altına alınabilir ve hatta geriye döndürülebilirler. (Turk J Ophthalmol 2013; 43: 270-7) Anah tar Ke li me ler: Psikotropik ilaç, oküler, yan etki, ters etki Introduction human eye becoming sensitive to psychotropic treatments. -

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)? Thioridazine (Mellaril) Tamoxifen

1 Q Systemic drugs and ocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)? Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at Thioridazine (Mellaril) doses <800 mg/d Tamoxifen Blair Witch cataract Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) develop Cidofovir Causes a crystalline retinopathy Isotretinoin (Accutane) Causes nyctalopia Rifabutin Yellow tinting of vision Digitalis Causes uveitis with hypopyon (Start with chlorpromazine and work down the list) 2 A Systemic drugs and retinalocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at Thioridazine (Mellaril) doses <800 mg/d Tamoxifen Blair Witch cataract Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) develop Cidofovir Causes a crystalline retinopathy Isotretinoin (Accutane) Causes nyctalopia Rifabutin Yellow tinting of vision Digitalis Causes uveitis with hypopyon 3 Systemic drugs and ocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine: Blair Witch cataract 4 Q Systemic drugs and retinalocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at ThioridazineWhat class of medicine (isMellaril chlorpromazine?) It is a phenothiazine doses <800 mg/d TamoxifenWhat sort of med are phenothiazines? Blair Witch cataract They are neuroleptics (but have other uses as well) Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) In addition to cataracts, what ophthalmic effects does develop high-dose chlorpromazine therapy have? CidofovirIt causes pigmentation of the lids and conj Causes a crystalline retinopathy IsotretinoinWhat -

Successful Treatment of Tardive Oculogyric Crisis with Bornaprine

Isr J Psychiatry - Vol. 56 - No 3 (2019) Şengül KOCamer ŞAHIN ET AL. Successful Treatment of Tardive Oculogyric Crisis with Bornaprine Şengül Kocamer Şahin, MD,1 Ayşegül Şahin Ekici, MD,1 Gulcin Elboga, MD,1 Abdurrahman Altindag, MD,1 and Atil Bisgin, MD2 1 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Turkey 2 Adana Genetics Diseases Diagnosis and Treatment Center and Medical Genetics Department of the Medical Faculty, Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey The presentation is a specific dystonic reaction. Recurrent ABSTRACT oculogyric crisis is different from the acute adverse drug event (4). It has been variously considered to be a form Tardive oculogyric crisis is one of the tardive syndromes of tardive dyskinesia (4). characterized by a spasmodic deviation of eyes typically Antipsychotic discontinuation is still the primary turning upwards after long-term use of high-potency suggestion regarding the management of tardive syn- typical or rarely atypical antipsychotics. Antipsychotic dromes, although no definitive evidence is supported. discontinuation is suggested as a treatment option with If this is not possible, changing to an antipsychotic with changing to an antipsychotic with a lower tardive dystonia a lower tardive dystonia (TDt) risk is the next option risk. Anticholinergic drugs such as trihexyphenidyl may (5). Antidyskinetic agents may be added to treatment also improve the symptoms of tardive dystonia, but these in patients whose symptoms persist despite drug regula- drugs may trigger or aggravate tardive dyskinesia. We tion. Antioxidants that reduce free oxygen radicals such report on a case with tardive syndromes and treatment as Ginkgo biloba, vitamin E, vitamin B6, clonazepam, challenge. -

Scientific Programme

Scientific programme The times mentioned below are Paris time FRIDAY 23rd APRIL 10.00 - 12.00 Orthoptic Education Forum 14.00 - 16.00 Interactive Strabismus Workshop SATURDAY 24th APRIL 08.30 - 09.00 Opening Ceremony 09.00 - 10.30 Free papers - Strabismus Surgery and Botulinum Toxin o Periosteal fixation of medial and lateral recti for large angle incomitant exotropia Gill Adams o Overcorrection after vertical muscle transposition with augmentation sutures in sixth nerve palsy Dina Hassanein o Strabismus surgery in patients with prior vitreoretinal surgery - strategies and results Jon Peiter Saunte o Double Y-splitting for Duane Syndrome with severe elevation on adduction Alain Spielmann o Robot-assisted simulated strabismus surgery Claude Speeg-Schatz o Axial length in strabismus surgery Hector Jimenez-Ortiz o Strabismus outcomes after surgery in France Quentin Colas o Treatment of strabismus using Bupivacaine & Botulinum Type A Toxin in patients who had prior unsuccessful surgical attempts Talita Cunha Namgalies o Bupivicaine Injection versus mini-Tenotomy for small angle horizontal strabismus in children Hala El Hilali 10.30 - 10.35 Introduction of Bielschovsky Lecturer Stephen Kraft - Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada 10.35 - 11.05 Bielschovsky Lecture - Nexus of Strabismus, Myopia and Glaucoma Joseph L. Demer - Stein Eye Institute, UCLA, Los Angeles, USA 11.35 - 12.35 Symposium Strabismus in High Myopia Update on Strabismus Surgery in High Myopia Tsuranu Yokoyama - Osaka City General Hospital Children's Medical Center, -

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo David Solomon, MD, Phd

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo David Solomon, MD, PhD Address Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania, 3 W. Gates Building, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-4283, USA. Email: [email protected] Current Treatment Options in Neurology 2000, 2:417–427 Current Science Inc. ISSN 1092-8480 Copyright © 2000 by Current Science Inc. Opinion statement Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can be diagnosed with great certainty, and treated effectively at the bedside using one of the canalith repositioning procedures described in this paper. This treatment has been shown effective in properly controlled trials, has a rational basis, and has minimal risk [1]. Introduction Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most rior SCC [7]. Convincing evidence [8, Class I] in support common diagnosis made in many specialty clinics serv- of canalithiasis as a pathophysiologic explanation for ing patients with dizziness. This diagnosis is suggested by BPPV validates treatment with any procedure that can a history of brief (less than one minute) episodes of ver- effectively clear these dense particles from the posterior tigo that are provoked by rolling over in bed, lying down, semicircular canal. Canalithiasis can occur in any canal. sitting up from a supine position, bending over, or look- The posterior semicircular canal (PSC) was affected in the ing up. BPPV commonly is worse in the early morning majority of cases of BPPV (93% of cases) [9], with 85% (matutinal vertigo), and may be absent for weeks or being unilateral, and 8% affecting the PSC on both sides. months at a time before returning. Diagnosis rests on the The horizontal semicircular canal (HSC) was affected in observation of characteristic eye movements accompany- 5% of cases. -

Ophthalmic Manifestations of Acute Leukaemias T Sharma Et Al 664

Eye (2004) 18, 663–672 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/04 $30.00 www.nature.com/eye 1 1 2 1 Ophthalmic T Sharma , J Grewal , S Gupta and PI Murray REVIEW manifestations of acute leukaemias: the ophthalmologist’s role Abstract neoplastic cells. Ophthalmic involvement can be classified into two major categories: (1) primary With evolving diagnostic and therapeutic or direct leukaemic infiltration, (2) secondary or advances, the survival of patients with acute indirect involvement. The direct leukaemic leukaemia has considerably improved. This infiltration can show three patterns: anterior has led to an increase in the variability of segment uveal infiltration, orbital infiltration, ocular presentations in the form of side effects and neuro-ophthalmic signs of central nervous of the treatment and the ways leukaemic system leukaemia that include optic nerve relapses are being first identified as an ocular infiltration, cranial nerve palsies, and presentation. Leukaemia may involve many papilloedema. The secondary changes are the ocular tissues either by direct infiltration, result of haematological abnormalities of haemorrhage, ischaemia, or toxicity due to leukaemia such as anaemia, thrombocytopenia, various chemotherapeutic agents. Ocular hyperviscosity, and immunosuppression. These involvement may also be seen in graft-versus- can manifest as retinal or vitreous haemorrhage, host reaction in patients undergoing infections, and as vascular occlusions. In some allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, or cases the ocular involvement may be simply as increased susceptibility to infections asymptomatic. In one prospective study, there as a result of immunosuppression that these was a high prevalence of asymptomatic ocular 1 patients undergo. This can range from simple Birmingham and Midland lesions in childhood acute leukaemia.1 In the era bacterial conjunctivitis to an endophthalmitis. -

Evidence Tables

6/9/2020 Evidence Tables Core A and Core B Lauren Koen, BSN, RN, MPA KATHY AUBERRY, DNP, RN, CDDN TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL CORE TRAINING EVIDENCE TABLES _____________________________________________________________________ 2 Evidence Table A: Scope and Significance of Health Issue/ Priority Group ______________________________________________________ 2 Evidence Table B: Training Methods/ Current Material _____________________________________________________________________ 3 CORE A EVIDENCE TABLES ____________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Evidence Table C: Universal Precautions, Inflammation, and Infection ________________________________________________________ 6 Evidence Table D: Vital Signs and Emergencies ___________________________________________________________________________ 9 Evidence Table E: Fatal Four and Sepsis ________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Evidence Table F: Developmental Disabilities and Dementia _______________________________________________________________ 15 Evidence Table G: Direct Support Professional Roles and Responsibilities _____________________________________________________ 19 Core B Evidence Tables ______________________________________________________________________________________ 22 Evidence Table H: Fundamentals for Pharmacology ______________________________________________________________________ 22 Evidence Table I: Rights and Documentation ____________________________________________________________________________