ESIA Appendix 2 Oyu Tolgoi Project Critical Habitat Assessment: IFC Performance Standard 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houbara Bustard and Saker Falcon Surveys In

WILDLIFE SCIENCE AND CONSERVATION CENTER OF MONGOLIA Public Disclosure Authorized Houbara Bustard and Saker Falcon surveys in Galba Gobi IBA, southern Mongolia Preliminary technical report to the World Bank and BirdLife International Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Nyambayar Batbayar, Bayarjargal Batsukh Wildlife Science and Conservation Center of Mongolia Jonathan Stacey Birdlife International and Axel Bräunlich consultant Public Disclosure Authorized 11/09/2009 Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Biodiversity issues in Mongolia’s South Gobi region .................................................................................. 3 Two globally threatened species under focus ............................................................................................... 4 Project aim .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Outputs .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Schedule of activities .................................................................................................................................... 6 Basic outline of Methods ............................................................................................................................. -

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia Th Th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 Days)

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia th th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 days) Caspian Snowcock by Alihan Vergiliel Turkey, a country the size of Texas, is a spectacular avian and cultural crossroads. This fascinating nation boasts an ancient history, from even before centuries of Greek Roman and Byzantine domination, through the 500-year Ottoman Empire and into the modern era. Needless to say, with such a pedigree the country holds some very impressive archaeological and cultural sites. Our tour of Eastern Turkey starts in the eastern city of Van, formerly known as Tuspa and 3,000 years ago the capital city of the Urartians. Today there are historical structures from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, and Urartian artifacts can be seen at its archaeological museum. RBL Turkey Itinerary 2 However, it is the birds that are of primary interest to us as here, at the eastern limits of the Western Palearctic, we expect to find some very special and seldom-seen species, including Mountain ‘Caucasian’ Chiffchaff, Green Warbler, Mongolian Finch and Grey-headed Bunting. Around the shores of Lake Van we will seek out Moustached and Paddyfield Warblers in the dense reed beds, while on the lake itself, our targets include Marbled Teal, the threatened White-headed Duck, Dalmatian Pelican, Pygmy Cormorant and Armenian Gull, plus a selection of waders that may include Terek and Broad-billed Sandpiper. As we move further north-east into the steppe and semi desert areas, we will attempt to find Great Bustards and Demoiselle Cranes, with a potential supporting cast of Montagu’s Harrier, Steppe Eagle, the exquisite Citrine Wagtail and Twite, to name but a few. -

The Phylogenetic Relationships and Generic Limits of Finches

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62 (2012) 581–596 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev The phylogenetic relationships and generic limits of finches (Fringillidae) ⇑ Dario Zuccon a, , Robert Pryˆs-Jones b, Pamela C. Rasmussen c, Per G.P. Ericson d a Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Bird Group, Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, Akeman St., Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK c Department of Zoology and MSU Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA d Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships among the true finches (Fringillidae) have been confounded by the recurrence Received 30 June 2011 of similar plumage patterns and use of similar feeding niches. Using a dense taxon sampling and a com- Revised 27 September 2011 bination of nuclear and mitochondrial sequences we reconstructed a well resolved and strongly sup- Accepted 3 October 2011 ported phylogenetic hypothesis for this family. We identified three well supported, subfamily level Available online 17 October 2011 clades: the Holoarctic genus Fringilla (subfamly Fringillinae), the Neotropical Euphonia and Chlorophonia (subfamily Euphoniinae), and the more widespread subfamily Carduelinae for the remaining taxa. Keywords: Although usually separated in a different -

Ararat Marz Guidebook

ARARAT MARZ GUIDEBOOK 2014 ARARAT FACTS ARARAT Ararat is one of Armenia’s 10 provinces, whose capital is Artashat. Named after Mount Ararat, the province borders Turkey to the west and Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic to the south. Two former Armenian capitals are located in this region, Artashat and Dvin, as well as the Khor Virap monastery, significant as the place of Gregory the Illuminator’s 13-year imprisonment and for being the closest point to Mount Ararat within Armenian borders. The province consists of 97 com- munities, known as hamaynkner, of which four are considered urban and 93 rural. Spanning an area of 1995 km2 and home to a population of 311,400 people, its administrative Center is Artashat which is 29km from Yerevan. Ararat borders the following provinces: Armavir to the northwest, Kotayk to the north, Gegharkunik 1. It is rumoured that Sir Winston’s favourite tipple came out of the Ararat valley in the east and Vayots Dzor to the southeast. Ararat also has a border with the city of Yerevan in the north, between its borders with Armavir and Kotayk. Ararat’s moun- tains include the Yeranos range, Vishapasar 3157m, Geghasar 3443m, and Kotuts 2061m, Urts 2445m. The province also has a number of lakes including: Sev, Azat, Armush, and Karalich as well as the Arax, Azat, Hrazdan, Yotnakunk, Vedi, and Artashat Rivers. During the period from 331 BC to 428 AD, the Armenian Kingdom was also known as Greater Armenia (Mets Hayk) and consisted of 15 states. One of those original states was Ayrarat. -

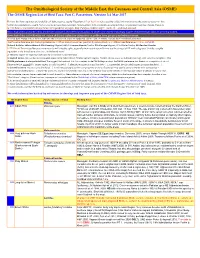

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

India's National Action Plan for Conservation of Migratory Birds and Their Habitats Along Central Asian Flyway

India’s National Action Plan for Conservation of Migratory Birds and their Habitats along Central Asian Flyway (2018-2023) CAF National Action Plan 2018 -India Drafting Committee: The Draft India National Action Plan for Conservation of Migratory Birds in Central Asian Flyway was prepared by the following committee constituted by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change: Dr. Soumitra Dasgupta, IG F (WL), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (Chairman) Dr. Nita Shah, Bombay Natural History Society (Member) Dr. Ritesh Kumar, Wetlands International South Asia (Member) Dr. Suresh Kumar, Wildlife Institute of India (Member) Mr. C. Sasikumar, Wildlife Division, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change The Committee met at Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur on December 12-13, 2017 and at the office of IG F (WL) on March 15, 2018 and April 12, 2018 to review drafts. The final draft National Action Plan was submitted by the Committee on April 14, 2018. Final review of the draft was done in the office of IG (WL) on May 8, 2018. [1] CAF National Action Plan 2018 -India Contents Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... 3 Preamble ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Goal and Objectives ......................................................................................................................... -

Birds of Ikh Nart Nature Reserve

24 Тоодог 2, 2016 BIRDS OF IKH NART NATURE RESERVE 1, 2, 3, 1 Mammallian Ecology laboratory, Institute of General and Experimental Biology, MAS, Peace Avenue, 54B, Ulaanbaatar 10351 2 Mongolian Bird Watching Club, Union Building, B-802, UNESCO Str., Ulaanbaatar 14210 3Department of Biology, National University of Mongolia, Ikh Surguuliin Str., Ulaanbaatar 14201 4 Theodor-Storm-Str. 11, 25813 Husum, Germany 5 Department of Conservation Biology, Denver Zoological Foundation, 2300 Steele Street, Denver, CO 80205, USA Corresponding author: [email protected] хураангуй. д оого г г г гдд оо дооод дд, гг г дг д гг гд гг оод оо г г д 20 д ггд г о г, д д ооо гддг гоо г д д одог г оо д оог дг оо Falco cherrug, гд Aquila nipalensis оо оодо оог г Aegypius monachus г д г г д дг д түлхүүр үг. д, г, оого abstract. , , 20 , Falco cherrug, Aquila nipalensis Aegypius monachus Key words: species composition, checklist, Dornogobi Тоодог 222, 2016 Introduction , et al 2006 16 , 1, 200, , et al 200, 2010 et al 200, 201 et al 200 et al, 2006 , , , , , , Baatargal et al. 25 Study area bird taxonomy and nomenclature, we generally followed the Oriental Bird Club’s species list. We Ikh Nart Nature Reserve (Ikh Nart) was established followed IUCN’s Red List (Birdlife International in 1996 to protect 66,600 ha of rocky outcrops 2015) data base for globally threatened status of in northwestern Dornogobi Province, Mongolia the species and used the Mongolian Bird Red List (Myagmarsuren 2000; Reading et al 2011) (Gombobaatar and Monks, 2009) for regional (Figure 1). -

Shirak Region Which Was Also After the Great Flood

NOTES: ARAGATSOTN a traveler’s reference guide ® Aragatsotn Marz : 3 of 94 - TourArmenia © 2008 Rick Ney ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - www.TACentral.com a traveler’s reference guide ® Aragatsotn Marz : 4 of 94 - TourArmenia © 2008 Rick Ney ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - www.TACentral.com a traveler’s reference guide ® soil surprisingly rich when irrigated. Unlike Talin INTRODUCTIONB Highlights the Southeast has deeper soils and is more heavily ARAGATSOTN marz Area: 2753 sq. km farmed. The mountain slopes receive more rainfall Population: 88600 ²ð²¶²ÌàîÜ Ù³ñ½ then on the plateau and has thick stands of Marz Capital: Ashtarak • Visit Ashtarak Gorge and the three mountain grass and wildflowers throughout the sister churches of Karmravor, B H Distance from Yerevan: 22 km By Rick Ney summer season. Tsiranavor and Spitakavor (p. 10)H MapsB by RafaelH Torossian Marzpetaran: Tel: (232) 32 368, 32 251 EditedB by BellaH Karapetian Largest City: Ashtarak • Follow the mountain monastery trail to Aragatsotn (also spelled “Aragadzotn”) is named Tegher (pp. 18),H Mughni (p 20),H TABLEB OF CONTENTS Hovhanavank (pp. 21)H and after the massive mountain (4095m / 13,435 ft.) that hovers over the northern reaches of Armenia. Saghmosavank (pp. 23)H INTRODUCTIONH (p. 5) The name itself means ‘at the foot of’ or ‘the legs NATUREH (p. 6) • See Amberd Castle, summer home for of’ Aragats, a fitting title if ever there was one for DOH (p. 7) Armenia’s rulers (p 25)H this rugged land that wraps around the collapsed WHEN?H (p. 8) volcano. A district carved for convenience, the • Hike up the south peak of Mt. -

ARMENIA (Via Georgia) in 2016

BIRD TOURISM REPORTS 4/2016 Petri Hottola ARMENIA (via Georgia) in 2016 Fig. 1. Late spring is the time of flowers in the Caucasus region. From 25th April to 6th May, 2016, I finally was able to travel to Armenia for birding, and also to realize my third visit in Georgia, after a long break since the nation became free of Russian rule. The journey was quite an enjoyable one and inspired me to write this report to help others to get there, too. I myself was particularly encouraged and helped by a 2014 report by two Swedes, Thomas Pettersson and Krister Mild. Vasil Ananian was also contacted in regard to Caspian Snowcock and he let me know the current situation, helping to avoid sites which have become empty or required a local guide. I have nothing against somebody employing a guide to guarantee a better success rate in this case, but being guided is not my personal preference. The main target species of the trip were as follows: For Georgia – Caucasian Grouse, Caucasian Snowcock, Güldenstädt’s Redstart and Great Rosefinch. For Armenia – Dalmatian Pelican, Caspian Snowcock, See-see Partridge, Radde’s Accentor, Eurasian Crimson-winged Finch, Mongolian Finch and Black-headed Bunting. Even though my life list already was around 7.300 in April 2016, I still missed some relatively common species such as the pelican and the bunting. The secondary target list, the Western Palaearctic region lifers, included: Red-tailed Wheatear, Upcher’s Warbler, Menetries’s Warbler, Eastern Rock Nuthatch, Wallcreeper, White-throated Robin, Red-fronted Serin, Grey-necked Bunting and Pale Rock Sparrow. -

Birds of Nepal an Official Checklist 2018

Birds of Nepal An Official Checklist Department of National Parks Bird Conservation Nepal and Wildlife Conservation 2018 Species Research and Contribution Anish Timsina, Badri Chaudhary, Barry McCarthy, Benzamin Smelt, Cagan Sakercioglu, Carol Inskipp, Deborah Allen, Dhan Bahadur Chaudhary, Dheeraj Chaudhary, Geraldine Werhahn, Hathan Chaudhary, Hem Sagar Baral, Hem Subedi, Jack H. Cox, Karan Bahadur Shah, Mich Coker, Naresh Kusi, Phil Round, Ram Shahi, Robert DeCandido, Sanjiv Acharya, Som GC, Suchit Basnet, Tika Giri, Tim Inskipp, Tulsi Ram Subedi and Yub Raj Basnet. Review Committee Laxman Prasad Poudyal, Dr. Hem Sagar Baral, Carol Inskipp, Tim Inskipp, Ishana Thapa and Jyotendra Jyu Thakuri Cover page drawing: Spiny Babbler by Craig Robson Citation: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Bird Conservation Nepal (2018). Birds of Nepal: An Official Checklist, Kathmandu, Nepal. Great Thick-knee by Jan Wilczur 1 Update and taxonomy note This official checklist is based on “Birds of Nepal: An official checklist” updated and published by Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Bird Conservation Nepal in year 2016. New additions in this checklist are as below, New recorded species Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus Rufous-tailed Rock- thrush Monticola saxatilis Himalayan Grasshopper-warbler Locustella kashmirensis New species after split (HBW and BirdLife International 2017) Indian Scops-owl Otus bakkamoena, split from Collared Scops-owl Otus lettia Eastern Marsh-harrier Circus spilonotus, split from western Marsh-harrier Circus aeruginosu Indochinese Roller Coracias affinis, split from Indian Roller Coracias benghalensis Indian Nuthatch Sitta castanea, split from Chestnut-bellied Nuthatch Sitta cinnamoventris Chinese Rubythroat Calliope tschebaiewi, split from Himalayan Rubythroat Calliope pectoralis This checklist follows the BirdLife International’s taxonomy; HBW and BirdLife International (2017) Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. -

![Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf R/Fx?](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9632/birds-of-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-r-fx-4259632.webp)

Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf R/Fx?

Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf r/fx? National Trust for Annapurna Conservation Nature Conservation Birds of AnnapurnaArea Conservation Project Area 80 2018 Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf r/fx? National Trust for Annapurna Conservation Nature Conservation Area Project 2018 Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf r/fx? Published by: National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC), Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) Review Committee Carol Inskipp, Dr. Hem Sagar Baral and Dr. Naresh Subedi Compilation Rishi Baral (Conservation Officer – NTNC-ACAP) Suggested Citation: Baral R., (2018). Birds of Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal pp. 74 All rights reserved © National Trust for Nature Conservation First Edition 700 Copies ISBN: 978-9937-8522-5-8 Front Cover Art: Cheer Pheasant (Catreus wallichii) by Roshan Bhandari Title Page Photo: Nest with Eggs by Rishi Baral Back Cover Photo: Spiny Babbler (Turdoides nipalensis) by Manshanta Ghimire Design and Layout by: Sigma General Offset Press, Kathmandu National Trust for Annapurna Conservation Printed : Sigma General Offset Press, Sanepa, Lalitpur, 5554029 Nature Conservation Area Project 2018 Table of Contents Forewords Acknowledgements Abbreviations Nepal’s Birds Status Birds of Annapurna National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC) 1-2 Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) 3-5 Hotspot of Birds in Annapurna Conservation