Haydn's Three-Part Expositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 in D Minor, Op. 70

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Antonín Dvořák Born September 8, 1841, Mü hlhausen, Bohemia (now Nelahozeves, Czech Republic). Died May 1, 1904, Prague, Czechoslovakia. Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 Dvořák began sketching this symphony in 1884; finished the score on March 17, 1885; and conducted the first performance on Ap ril 22 of that year in London. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty -five minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Dvořák’s Seventh Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 9 and 10, 1894, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on February 21, 22, and 23, 2002, with Franz Welser -Möst conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 9, 1968, with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski conducting, and most recently on July 19, 2003, with James Conlon conduct ing. To the late nineteenth century, Dvořák was the composer of five symphonies. His first four symphonies, never published during his lifetime, were unknown. This powerful D minor work was published in 1885 as Symphony no. 2, simply because it w as the second symphony by Dvořák to come off the printer’s press, even though it was the seventh to come from the composer’s pen. Dvořák , who was perhaps the only one capable of setting the record straight, didn’t, when, at the top of this manuscript , wrot e Symphony no. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Annual Journals

Annual Journals Volume 37, 2015 Priced £5 John McCabe – A mosaic of memories, by Martin Cotton; Jacob’s Ladder (part 2) – How Gordon Jacob became a composer, by Tully Potter; Arthur Butterworth – A life in music, by Paul Conway; The reception of Humphrey Searle, by John France; Algernon Ashton – another forgotten English composer, by Patrick Webb; Obituaries of John McCabe, Peter Sculthorpe, Patrick Gowers and Ian Kellam Volume 36, 2014 Priced £5 Jacob’s Ladder (part 1) – How Gordon Jacob became a composer, by Tully Potter; Music of the Cactus Land – a consideration of musical style and text setting in The Hollow Men of Denis ApIvor, by Mark Marrington; The Life and Music of William Lloyd Webber, by John France; “On making operas from novels, and Britten’s legacy” – an interview with John Joubert, by David Chandler; Obituaries of Antony Hopkins, Patric Standford, Malcolm Macdonald and Myer Fredman Volume 35, 2013 Priced £5 “Imogen Holst, Benjamin Britten, and related activity”, by Dr Christopher Tinker; “One foot in Eden” – Ronald Center’s centenary, by Dr James Reid Baxter; Frances Joan Singleton, pianist and accompanist: A perfect wonder, by Michael Slaytor; Richard Henry Walthew – composer, conductor, pianist and teacher, by Peter Atkinson Volume 34, 2012 Priced £5 The Orchestral Music of Sir Edward German, by Ray Siese; Edward Cympson and the Victorian Drawing Room Operetta,by David Chandler; Dramatic structures with an emotive intention: The Symphonies of Daniel Jones (1912-1993), by Paul Conway; British Piano Music of the 20th Century, by Richard Deering; John Foulds’ A World Requiem: an unjustified obscurity, by Laura Rakotonirina; ‘From Disaster to Triumph’ – a selection of British operas composed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II up to the time of her Diamond Jubilee, by Stan Meares. -

PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ludwig van Beethoven Born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany. Died March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria. Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68 (Pastoral) Beethoven composed this symphony in the fall of 1807 and the early part of 1808, and conducted the first performance on December 22, 1808, in Vienna. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, two trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 2 and 3, 1894, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on September 21, 22, 23, and 26, 2006, with Myung-Whun Chung conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 16, 1938, with Willem van Hoogstraten conducting, and most recently on July 25, 1998, with Edo de Waart conducting. Even by nineteenth-century standards, the historic concert on December 22, 1808, was something of an endurance test. That night, Beethoven conducted the premieres of both his Fifth and Pastoral symphonies, played his Fourth Piano Concerto (conducting from the keyboard); and rounded out the program with the Gloria and the Sanctus from the Mass in C; the concert aria Ah! perfido; improvisations at the keyboard, and the Choral Fantasy, written in great haste at the last moment as a grand finale. If concertgoers that evening read their printed program—the luxury of program notes still many decades in the future—they would have found the following brief guide to the Sixth Symphony, in Beethoven’s own words: Pastoral Symphony, more an expression of feeling than painting. -

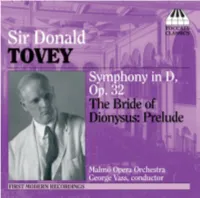

Toccata Classics TOCC 0033 Notes

DONALD FRANCIS TOVEY (1875–1940) SYMPHONY IN D – THE BRIDE OF DIONYSUS Prelude by Peter R. Shore Donald Francis Tovey: An Introduction Sir Donald Tovey, the Reid Professor of Music at Edinburgh University from 1914 until his death in 1940, is best remembered as the author of a series of Essays in Musical Analysis.1 But Tovey regarded himself first and foremost as a musician: making music was the real business of his life; everything else was secondary. Born on 17 July 1875 at Eton, Tovey was the younger son of the Reverend Duncan Crookes Tovey and his wife, Mary. At the time of Donald’s birth his father was assistant master of classics at Eton College but he eventually became rector of the parish of Worplesdon in Surrey, just north of Guildford. Neither of his parents was musical, but their elder as well as their younger son had, to different degrees, a gift for music. The extent of Tovey’s musicality was recognised not by his family but by a Miss Sophie Weiss, a piano-teacher and general musical educator who ran ‘Northlands’, a fashionable school at Englefield Green, near Windsor, and who took him as a pupil when he was five. She became his ‘musical mother’, and their association was to last for the rest of his life, with Miss Weisse acting first as tutor and then mentor. This relationship was to prove both a P blessing and a curse. Although the Reverend Tovey was a master at Eton College, Miss Weisse succeeded in preventing the young Donald from going to public school at all. -

BOULOGNE: Violin Concerto in a Minor, Op. 5, No. 2 Notes on the Program by Dr

BOULOGNE: Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 5, No. 2 Notes on the Program By Dr. Richard E. Rodda oseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint- (one of whose mulatto officers was the father of Georges, one of music history’s most the novelist Alexandre Dumas père), but he was fascinating figures, was born on Christmas accused of misappropriation of regimental funds and JDay 1745 on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, imprisoned at Houdainville for more than a year. He where his father, a French civil servant, was stationed was eventually cleared of the charge and released, as comptroller-general; his mother was a Black and made his way back to Paris, where he lived in islander. The family moved to Paris when the boy considerable poverty. He briefly became director of was ten. Joseph was enrolled in the academy of a new musical organization, Le Cercle de l’Harmonie, Nicolas Texier de La Boëssière, one of France’s most but died of a stomach ulcer in 1799. renowned fencing masters, and there received a good general education as well as rigorous training Boulogne’s music, agreeable and polished without in swimming, boxing, horse riding and other physical being profound, is in an early Classical idiom that and social skills; he became one of the finest fencers shows the influence of the Mannheim composers in Europe. Boulogne’s musical education was less and his French contemporaries. His seven operas well documented, though he apparently had shown met with little success, so his fame as a composer talent as a violinist even before leaving Guadeloupe rested primarily on his instrumental works: two and seems to have been a student of the celebrated symphonies, more than a dozen solo violin concertos composer François Gossec for several years. -

Phd for Hardbound July 16

‘THE PRACTICALITY OF THE IMPOSSIBLE’: STUDIES IN 20th- and 21st- CENTURY PIANO ÉTUDES Naomi Meghan Jia-Ling Woo Faculty of Music University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clare College July 2019 soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. It does not exceed 80,000 words. Naomi Woo 2019 ABSTRACT ‘THE PRACTICALITY OF THE IMPOSSIBLE’: STUDIES IN 20th- and 21st-CENTURY PIANO ÉTUDES NAOMI MEGHAN JIA-LING WOO This thesis examines piano études by John Cage, György Ligeti, Conlon Nancarrow, and Nicole Lizée that push the limits of the human body in performance. The thesis opens with an account of the origins of the piano étude in the works of Chopin and Liszt, situating it within the political, economic, and aesthetic conditions of the 19th century. Subsequently, sets of études by Cage, Ligeti, Nancarrow, and Lizée are studied, each using a different body of theoretical literature—including utopian thought, queer theory, and posthumanism—to understand how this limit manifests in musical works.