BOULOGNE: Violin Concerto in a Minor, Op. 5, No. 2 Notes on the Program by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

Allentown Symhpony Orchestra Audition

ALLENTOWN SYMHPONY ORCHESTRA AUDITION REQUIREMENTS VIOLIN SECTION ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER & ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL SECTION: Orchestral Excerpts: Brahms Symphony No. 4, Movement I 1. m. 392 to the downbeat of m. 426 Mozart Symphony no. 39, Movement II 2. m. 1 to the end of m. 56 Mozart Symphony no. 39, Movement IV 3. m. 1 to m. 53 Mendelssohn Midsummer’s Night Dream - Scherzo 4. m. 17 to the downbeat of 7 ms. after reh. D Schumann Symphony no. 2 – Movement II - Scherzo 5. Coda (pick-ups to m. 362 to end of m. 397) Prokofiev Symphony no. 1 “Classical” – Movement I 6. beginning to 4 ms. after reh. E R. Strauss Don Juan 7. beginning to the downbeat of 13 ms. after reh. C Beethoven Symphony no. 9 – Movement III 8. Lo’stesso tempo (m. 99 to the end of m. 114) Brahms Symphony no. 1 – Movement IV 9. Reh. A to 2 ms. before reh. B (m. 22 to the end of m. 28) 10. Pick-up to 1 m. before reh. D to the downbeat of 5ms. after reh. F Smetana Bartered Bride Overture (violin 2 part) 11. beginning to the end of m. 33. CONCERTMASTER ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL (In addition to Section Repertoire) Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade, op. 35 (solos) Movement I 12. m. 14 to the downbeat of m. 18 13. Reh. C to the downbeat of reh. D 14. Reh G to the downbeat of reh. H Movement II 15. m. 1 to the downbeat of m. 5 Movement III 16. 8 ms. after reh. K to the end of b. -

The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting

Theory of Conducting – Chapter 1 The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting In a changing culture and a society that adopts and discards values (or anti-values) with a speed similar to that of fashion as related to dressing or speech, each profession must find out the roots and principles that provide an unchanging point of reference, those principles to which we are obliged to go back again and again in order to maintain an adequate direction and, by carrying them out, allow oneself to be fulfilled. Orchestral Conducting is not an exception. For that reason, some ideas arise once and again all along this work. Since their immutability guarantees their continuance. It is known that Music, as an art of performance, causally interlinks three persons: first and closely interlocked: the composer and the performer; then, eventually, the listener. The composer and his piece of work require the performer and make him come into existence. When the performer plays the piece, that is to say when he makes it real, perceptive existence is granted and offers it to the comprehension and even gives the listener the possibility of enjoying it. The composer needs the performer so that, by executing the piece, his work means something for the listener. Therefore, the performer has no self-existence but he is performer due to the previous existence of the piece and the composer, to whom he owes to be a performer. There exist a communication process between the composer and the performer that, as all those processes involves a sender, a message and a receiver. -

Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

CONDUCTING FROM THE PIANO: A TRADITION WORTH REVIVING? A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: MOZART’S PIANO CONCERTO IN C MINOR, K. 491 Eldred Colonel Marshall IV, B.A., M.M., M.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor David Itkin, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Marshall IV, Eldred Colonel. Conducting from the Piano: A Tradition Worth Reviving? A Study in Performance Practice: Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 74 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. Is conducting from the piano "real conducting?" Does one need formal orchestral conducting training in order to conduct classical-era piano concertos from the piano? Do Mozart piano concertos need a conductor? These are all questions this paper attempts to answer. Copyright 2018 by Eldred Colonel Marshall IV ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONDUCTING FROM THE KEYBOARD ............ 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT IS “REAL CONDUCTING?” ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 3. ARE CONDUCTORS NECESSARY IN MOZART PIANO CONCERTOS? ........................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 “Jeunehomme” (1777) ............................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major, K. 415 (1782) ............................................................. 23 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785) ............................................................. 25 Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

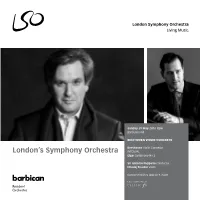

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers -

Music Director Riccardo Muti Returns to Cso for Two Weeks of Concerts in February

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: January 14, 2016 Eileen Chambers, 312.294.3092 Photos Available By Request: [email protected] MUSIC DIRECTOR RICCARDO MUTI RETURNS TO CSO FOR TWO WEEKS OF CONCERTS IN FEBRUARY February 11–20, 2016 CSO Principal Clarinet Stephen Williamson and CSO Concertmaster Robert Chen Make Solo Appearances with Muti and CSO Muti and Members of CSO Offer Lenten Performance of Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Our Savior on the Cross with Archbishop Blase J. Cupich at Holy Name Cathedral on February 19 CHICAGO—Music Director Riccardo Muti returns to Chicago in February for two weeks of concerts and activities February 11-20 during the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 125th anniversary season. Programs include subscription concerts featuring CSO Principal Clarinet Stephen Williamson (February 11-14) and CSO Concertmaster Robert Chen (February 18-20), a Lenten performance at Holy Name Cathedral with members of the CSO and Archbishop Blase J. Cupich on February 19 and an Open Rehearsal with the Festival Orchestra of the 2016 Chicago Youth in Music Festival on February 15. On February 11-14, Muti leads a program that highlights the CSO strings in a diverse array of works including György Ligeti’s haunting work for string orchestra, Ramifications, and Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for String Orchestra. The previously-announced premiere of CSO Mead Composer-in-Residence Elizabeth Ogonek’s new work for strings and percussion commissioned for the CSO has been postponed until a future date to be announced. Replacing the Ogonek work on the program is Arvo Pärt’s Orient and Occident, an intense and evocative work for strings in a first-ever performance by the CSO. -

An Investigation of Dalcroze-Inspired Embodied Movement

AN INVESTIGATION OF DALCROZE-INSPIRED EMBODIED MOVEMENT WITHIN UNDERGRADUATE CONDUCTING COURSEWORK by NICHOLAS J. MARZUOLA Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Nathan B. Kruse Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2019 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Nicholas J. Marzuola, candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. (signed) Dr. Nathan B. Kruse (chair of the committee) Dr. Lisa Huisman Koops Dr. Matthew L. Garrett Dr. Anthony Jack (date) March 25, 2019 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 2 Copyright © 2019 by Nicholas J. Marzuola All rights reserved 3 DEDICATION To Allison, my loving wife and best friend. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 11 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER ONE, INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 15 History of Conducting .................................................................................................. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 in D Minor, Op. 70

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Antonín Dvořák Born September 8, 1841, Mü hlhausen, Bohemia (now Nelahozeves, Czech Republic). Died May 1, 1904, Prague, Czechoslovakia. Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 Dvořák began sketching this symphony in 1884; finished the score on March 17, 1885; and conducted the first performance on Ap ril 22 of that year in London. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty -five minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Dvořák’s Seventh Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 9 and 10, 1894, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on February 21, 22, and 23, 2002, with Franz Welser -Möst conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 9, 1968, with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski conducting, and most recently on July 19, 2003, with James Conlon conduct ing. To the late nineteenth century, Dvořák was the composer of five symphonies. His first four symphonies, never published during his lifetime, were unknown. This powerful D minor work was published in 1885 as Symphony no. 2, simply because it w as the second symphony by Dvořák to come off the printer’s press, even though it was the seventh to come from the composer’s pen. Dvořák , who was perhaps the only one capable of setting the record straight, didn’t, when, at the top of this manuscript , wrot e Symphony no. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father.