Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beethoven 32 Plus

FREIES MUSIKZENTRUM STUTTGART FMZ Freies Musikzentrum Am Roserplatz Stuttgarter Str. 15 B e e t h o v e n 3 2 p l u s 0711 / 135 30 10 Die Konzertreihe im FMZ Saison 2008/2009 Die 32 Sonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven sind fester Bestandteil der Konzertliteratur. Immer wieder haben große Pianisten diesen Zyklus aufgeführt und auf unzähligen Schallplatten und CDs eingespielt. Bücher und Publikationen beschäftigen sich mit den Werken und den Interpreta- tionen. Und immer wieder hat es den Reiz, des Besonderen, wenn diese Werke wieder neu er- klingen. Als bekannt wurde, dass der österreichische Pianist Till Fellner sich für die nächsten beiden Kon- zertjahre diesen Zyklus als Projekt vorgenommen hatte, begann Andreas G. Winter, Leiter des FMZ und verantwortlich für die Programmgestaltung, als er Till Fellner dafür gewinnen konnte, diesen Zyklus, den Fellner auch in Wien, London, Paris, Tokio und New York spielt, auch im FMZ üeine Konzeption zu der Reihe „32 “zu entwickeln. Um die 32 Klavier- sonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven, deren erste 3 Abende Fellner in dieser Saison (weitere 4 A- bende in der nächsten) spielen wird, konnte Winter weitere namhafte Interpreten gewinnen, die Werke des großen Komponisten der Aufklärung in Zusammenhang mit Kompositionen von Schubert, Schumann und Brahms stellen werden. Paul Lewis wird die Diabelli-Variationen und Schuberts Impromptus D 935, der Geiger Erik Schu- mann mit Olga Scheps Violinsonaten von Beethoven und Brahms, das Trio Wanderer Klaviertrios von Beethoven und Schubert, der Tenor Marcus Ullmann in einem Liederabend neben „die ferne “Lieder von Schumann und Brahms und in einem Recital mit Mikael Samsonov, der frisch üSolocellist des SWR Radiosinfoieorchesters Stuttgart Sonaten von Beethoven und Schubert und Ben Kim, der dem Publikum bereits aus der letzten Saison in bester Erinnerung ist, mit einem Klavierabend Beethoven und Liszt interpretieren. -

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

[email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH to CO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 7, 2018 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5700; [email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH TO CONDUCT THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC MOZART’s Piano Concerto No. 22 with TILL FELLNER in His Philharmonic Debut BRUCKNER’s Symphony No. 9 April 19, 21, and 24, 2018 Christoph Eschenbach will conduct the New York Philharmonic in a program of works by Austrian composers: Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22, with Austrian pianist Till Fellner as soloist in his Philharmonic debut, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 (Ed. Nowak), Thursday, April 19, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Saturday, April 21 at 8:00 p.m.; and Tuesday, April 24 at 7:30 p.m. German conductor Christoph Eschenbach began his career as a pianist, making his New York Philharmonic debut as piano soloist in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in 1974. Both Christoph Eschenbach and Till Fellner won the Clara Haskil International Piano Competition, in 1965 and 1993, respectively. Mr. Fellner subsequently recorded Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22 on the Claves label in collaboration with the Clara Haskil Competition. The New York Times wrote of Mr. Eschenbach’s conducting Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 with the New York Philharmonic in 2008: “Mr. Eschenbach, a compelling Bruckner interpreter, brought a sense of structure and proportion to the music without diminishing the qualities of humility and awe that make it so gripping. … the orchestra responded with playing of striking power and commitment.” Artists Christoph Eschenbach is in demand as a distinguished guest conductor with the finest orchestras and opera houses throughout the world, including those in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Milan, Rome, Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Madrid, Tokyo, and Shanghai. -

October 8, 2011 Program

Susquehanna Symphony Orchestra Sheldon Bair, Founder & Music Director October 8, 2011 • professional instruction for infants, toddlers, youth and adults • guest artist series • private lessons in all instruments and voice . .where.w music is magic • group performance Onn thet Campus of John Carroll School class 701701 Churchville Road | Bel Air, MD 21014 410.399.9900410. • ensembles OnOn thet Corner of Union Ave. & Warren St. • recitals and community 500A500A Warren St. | Havre de Grace, MD 21078 performance 410.939.80804100. musicismagic.commus We’reWe’re more than justju2ust privatep lessons. Our 35th Season The Susquehanna Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1978 by Sheldon Bair and is a community orchestra of professional and amateur volunteer musicians. The Susquehanna Symphony’s home is in Harford County, Maryland, near the mouth of the Susquehanna River. The Orchestra performs a subscription series of concerts every year in addition to outdoor and chamber music concerts. The Orchestra has performed opera and ballet, as well as standard orchestral repertoire, and is known for its premieres of new works and performances of unusual repertoire. The Orchestra performed in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York City for over 3,000 people in November 2007, and at Carnegie Hall for 2,500 people in October 2009. This year marks the 35th Season of the Susquehanna Symphony Orchestra. Such longevity would not be possible without your support. We thank you for attending this evening’s concert, and look forward to many more years of making music! Mission Statement The Susquehanna Symphony Orchestra (SSO) strives to stimulate creativity and intellectual growth in the local community and volunteer musicians through the performance of diverse orchestral works. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

Music Appreciation April 23, 2020

Music Virtual Learning Music Appreciation April 23, 2020 Music Appreciation Lesson: April 23, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: Students will learn about the romantic era composers and their contributions to classical music. Bell Work Painting by Casper David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Take a look at this painting & think about what you have learned about the romantic era: Write about two emotions you see expressed in this famous painting? In what ways has the artist expressed those emotions? ● Romanticism encouraged artists to seek individual paths of expressing emotions. ● Romantics valued nature, the supernatural, myths, realm beyond the everyday, and national pride. ● Political and economic events impacted the way composers wrote music and artists expressed their emotions. Lesson Franz Lizst Franz Liszt ● Born: 1811 ● Hungarian composer ● Virtuoso at playing and composing ● Credited with the creation of the symphonic poem- an extended single movement work for orchestra inspired by paintings, plays, poems or other literary or visual works expressed through music. ● Famous works: Rhapsody no. 2 & La Campanella Feliz Mendelossohn Felix Mendelossohn ● Born in Germany: 1809 ● Child prodigy ● Composed the incidental music for Shakespeare’s play “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” ● Was also inspired to compose through his travels. ● Notable pieces: Scherzo from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and the Fingal’s Cave Overture, also known as the Hebrides, in reference to the rocky coast and ancient caverns of Scotland. Robert Schumann Robert Schumann ● Born: 1810 ● Focused on one genre of composing at a time. Piano was his first and most prolific. ● Married Clara Wieck, daughter of his first music teacher ● Promoted the music of Chopin, Berlioz and Brahms-all were close friends. -

Roberts on Carter Final

Karl Amadeus Hartmann: The Politics of Musical Inner Emigration Larson Powell Musik-Konzepte, Neue Folge no. 147 (March 2010), edited by Ulrich Tadday. Munich: edition text und kritik. 148 pp., with photographs and music examples. Die politische Theorie in der neuen Musik: Karl Amadeus Hartmann und Hannah Arendt, by Raphael Woebs. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2010. 162 pp. Verkettungen und Querstände. Weberns Schüler Karl Amadeus Hartmann und Ludwig Zenk und die politischen Implikationen ihres kompositorischen Handelns vor und nach 1945, by Marie-Therese Hommes. Basel: Edition Argus, 2010. 444 pp., with music examples. The waning of old-modernist models of history, Adorno's chief among them, has made possible the reevaluation of composers once overshadowed by the modernist mainstream. In the case of Karl Amadeus Hartmann, this reconsideration has taken several forms: looking at his symphonies within the larger history of the genre, re-appraising his role as a public postwar musical figure responsible for Munich's Musica Viva concerts,1 and also examining the nature of his political engagement. Hartmann can thus fruitfully be compared to composers such as Eisler and Dessau, whose work served more overt political aims than his own.2 Several recent publications address directly the question of Hartmann's political stance and its musical realization. Vindicating Hartmann as a political composer is no easy matter: not only must one face the far from unambiguous role he played from 1933-1945,3 but one must also rehabilitate the very possibility of political music itself, against its discreditation within the modernist mainstream. Principled appeals to ethics or to Hannah Arendt's political theories must thus be grounded in close musical analysis to be more than a mere rhetorical gesture. -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

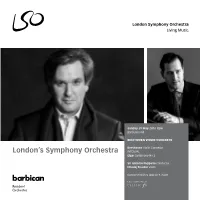

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers