Phd for Hardbound July 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

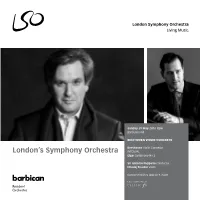

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Doktorska Disertacija

UNIVERZITET UMETNOSTI U BEOGRADU Interdisciplinarne studije Teorija umetnosti i medija Doktorska disertacija: Studije izvođačkih umetnosti: performativnost i funkcija telesnog gesta u pijanizmu autor: Marija Dinov Vasić mentor: dr Marija Masnikosa, vanr. prof. Beograd, jun 2019. god. Mentor: dr Marija Masnikosa, vanredni profesor, Univerzitet umetnosti u Beogradu, Fakultet muzičke umetnosti, Katedra za muzikologiju Članovi komisije za ocenu i odbranu: dr Tijana Popović Mlađenović, redovni profesor, Univerzitet umetnosti u Beogradu, Fakultet muzičke umetnosti, Katedra za muzikologiju dr Marina Marković, redovni profesor, Univerzitet umetnosti u Beogradu, Fakultet dramskih umetnosti, Katedra za glumu dr Nevena Daković, redovni profesor, Univerzitet umetnosti u Beogradu, Fakultet dramskih umetnosti, Katedra za Teoriju i istoriju dr Ivana Medić, naučni saradnik, Muzikološki institut SANU 1 Apstrakt Doktorska disertacija Studije izvođačkih umetnosti: Performativnost i funkcija telesnog gesta u pijanizmu je diskusija o telesnim pokretima (kinestetičkim gestovima) koje u svojim izvođenjima demonstriraju pijanisti, kako bi u jednoj sinergijskoj (auditivno-vizuelnoj) izvođačkoj formi otelotvorili muzičko-poetski sadržaj. Naučna rasprava izvedena je u formi fenomenološke studije, a za predmet istraživanja određena je pijanistička izvođačka umetnost. Temeljni postulati pijanizma sagledani su kroz prizmu njegovog esencijalnog fenomena – pijanističkog gesta. Definicija ovog fenomena izvedena je preko Šenkerove teze prema kojoj suština pijanističkog -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“Music of Our Time” When I worked at Columbia Records during the second half of the 1960s, the company was run in an enlightened way by its imaginative president, Goddard Lieberson. Himself a composer and a friend to many writers, artists, and musicians, Lieberson believed that a major record company should devote some of its resources to projects that had cultural value even if they didn’t bring in big profits from the marketplace. During those years American society was in crisis and the Vietnam War was raging; musical tastes were changing fast. It was clear to executives who ran record companies that new “hits” appealing to young people were liable to break out from unknown sources—but no one knew in advance what they would be or where they would come from. Columbia, successful and prosperous, was making plenty of money thanks to its Broadway musical and popular music albums. Classical music sold pretty well also. The company could afford to take chances. In that environment, thanks to Lieberson and Masterworks chief John McClure, I was allowed to produce a few recordings of new works that were off the beaten track. John McClure and I came up with the phrase, “Music of Our Time.” The budgets had to be kept small, but that was not a great obstacle because the artists whom I knew and whose work I wanted to produce were used to operating with little money. We wanted to produce the best and most strongly innovative new work that we could find out about. Innovation in those days had partly to do with creative uses of electronics, which had recently begun changing music in ways that would have been unimaginable earlier, and partly with a questioning of basic assumptions. -

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 By Peter T. Humphrey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor James Q. Davies, Chair Professor Nicholas de Monchaux Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Nicholas Mathew Spring 2021 Abstract A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T. Humphrey Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor James Q. Davies, Chair This dissertation argues that a cinematic approach to music recording developed during the 1950s, modeling the recording process of movie producers in post-production studios. This approach to recorded sound constructed an imaginary listener consisting of a blank perceptual space, whose sonic-auditory experience could be controlled through electroacoustic devices. This history provides an audiovisual genealogy for electroacoustic sound that challenges histories of recording that have privileged Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph and the recording industry it generated. It is elucidated through a consideration of the use of electroacoustic technologies for music that centered in Hollywood and drew upon sound recording practices from the movie industry. This consideration is undertaken through research in three technologies that underwent significant development in the 1950s: the recording studio, the mixing board, and the synthesizer. The 1956 Capitol Records Studio in Hollywood was the first purpose-built recording studio to be modelled on sound stages from the neighboring film lots. The mixing board was the paradigmatic tool of the recording studio, a central interface from which to direct and shape sound. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Nkinformer December 2019.Pdf

The NKInformer A newsletter of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research Donald C. Goff, MD, Director Antonio Convit, MD, Deputy Director Thomas O’Hara, MBA, Deputy Director, Institute Administration November – December 2019 Stuart Moss, MLS, Editor COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS The Memory Education and Research Initiative (MERI) Program Celebrates 17 Years of Service and 2020 Funding Front: Anne Schatz, Katie Brundage, Chelsea Reichert Plaska Rear: Antero Sarreal, Nunzio Pomara, Vita Pomara, Randy Hernando What is the MERI program? in the Geriatrics Division. A primary goal of the MERI program was to identify and provide early diagnosis The MERI program was started by Dr. Nunzio for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The program has Pomara (Geriatric Psychiatry) in 2003 with the help blossomed over the last 17 years and now follows of Dr. John Sidtis (Brain and Behavior Lab) and Dr. more than 1,200 individuals from Rockland County Lisa Willoughby, a former post-doctoral researcher and the surrounding areas. Community members Why is the MERI program unique? who take part in the MERI receive an extensive The MERI program is the only service of its kind in three to four-hour evaluation which includes Rockland County. According to the Rockland County neuropsychological assessment, a clinical Directory of Services, there are just two places that evaluation, and a psychiatric evaluation by Dr. residents can contact to get a free memory Pomara. Each participant receives a report of their screening: 1) the MERI program at NKI or 2) the performance on the neuropsychological assessment Alzheimer’s Association of Rockland County. While as well as recommendations. -

Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 in D Minor, Op. 70

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Antonín Dvořák Born September 8, 1841, Mü hlhausen, Bohemia (now Nelahozeves, Czech Republic). Died May 1, 1904, Prague, Czechoslovakia. Symphony No. 7 in D Minor, Op. 70 Dvořák began sketching this symphony in 1884; finished the score on March 17, 1885; and conducted the first performance on Ap ril 22 of that year in London. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty -five minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Dvořák’s Seventh Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 9 and 10, 1894, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on February 21, 22, and 23, 2002, with Franz Welser -Möst conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 9, 1968, with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski conducting, and most recently on July 19, 2003, with James Conlon conduct ing. To the late nineteenth century, Dvořák was the composer of five symphonies. His first four symphonies, never published during his lifetime, were unknown. This powerful D minor work was published in 1885 as Symphony no. 2, simply because it w as the second symphony by Dvořák to come off the printer’s press, even though it was the seventh to come from the composer’s pen. Dvořák , who was perhaps the only one capable of setting the record straight, didn’t, when, at the top of this manuscript , wrot e Symphony no.