Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“Music of Our Time” When I worked at Columbia Records during the second half of the 1960s, the company was run in an enlightened way by its imaginative president, Goddard Lieberson. Himself a composer and a friend to many writers, artists, and musicians, Lieberson believed that a major record company should devote some of its resources to projects that had cultural value even if they didn’t bring in big profits from the marketplace. During those years American society was in crisis and the Vietnam War was raging; musical tastes were changing fast. It was clear to executives who ran record companies that new “hits” appealing to young people were liable to break out from unknown sources—but no one knew in advance what they would be or where they would come from. Columbia, successful and prosperous, was making plenty of money thanks to its Broadway musical and popular music albums. Classical music sold pretty well also. The company could afford to take chances. In that environment, thanks to Lieberson and Masterworks chief John McClure, I was allowed to produce a few recordings of new works that were off the beaten track. John McClure and I came up with the phrase, “Music of Our Time.” The budgets had to be kept small, but that was not a great obstacle because the artists whom I knew and whose work I wanted to produce were used to operating with little money. We wanted to produce the best and most strongly innovative new work that we could find out about. Innovation in those days had partly to do with creative uses of electronics, which had recently begun changing music in ways that would have been unimaginable earlier, and partly with a questioning of basic assumptions. -

Transitions-Review-1.Pdf

ENCORE > ARTS COUNCIL MALTA WHETHER IT’S A BACH FUGUE, A MOZART SONATA OR A CHOPIN NOCTURNE, THE SCORE IS THE ONLY LINK BETWEEN THE PIANIST AND THE COMPOSER. BUT WHAT IF TODAY’S CONCERT PIANIST COULD ACTUALLY CONSULT THE COMPOSER HIMSELF? FOR PIANIST TRICIA DAWN WILLIAMS, CONVERSING WITH THE COMPOSER IS NOT A SÉANCE WITH THE DEPARTED BECAUSE SHE SPECIALISES IN CONTEMPORARY REPERTOIRE AND IN MOST CASES THE COMPOSER IS ALIVE AND KICKING. THANKS TO ARTS COUNCIL MALTA’S CULTURAL EXPORT FUND, WILLIAMS TRAVELLED TO NEW YORK FOR MASTER CLASSES WITH PIANIST MARGARET LENG TAN; A MUSIC JOURNEY THAT TOOK HER FROM THE PRINTED SCORES TO AN ENCOUNTER WITH AMERICAN COMPOSER GEORGE CRUMB ENCORE > ARTS COUNCIL MALTA In 2015, Tricia Dawn Williams decided to tackle the ground-breaking work Makrokosmos by George Crumb which is divided into two volumes: Volume I SHE HAS was composed in 1972 and Volume II in 1973. This monumental work is unlike any other piece ever PROGRESSIVELY written for the piano. In fact Makrokosmos remains the most comprehensive and influential exploration PERFECTED of the new technical resources of the piano from the twentieth century. One of the major challenges of this work is that it requires the pianist to exercise many AN INDIVIDUAL unorthodox playing practices, like plucking strings inside the piano, playing glissandi across strings, STYLE FUSING sliding a scrape along a string, damping the strings with various objects (like paper, a metal chain, glass) SOUND, as well as whistling tones and vocal utterances. This dazzling exploration of musical timbre is probably the CHOREOGRAPHY most famous aspect of Makrokosmos. -

PROBES #23.2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #23.2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. Auxiliaries PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s conceptual The PROBES Auxiliaries collect materials related to each episode that try to give contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and expose the a broader – and more immediate – impression of the field. They are a scan, not a search for a new sonic language made urgent after the deep listening vehicle; an indication of what further investigation might uncover collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks and, for that reason, most are edited snapshots of longer pieces. We have tried to at the many probes and experiments that were launched in light the corners as well as the central arena, and to not privilege so-called the last century in search of new musical resources, and a serious over so-called popular genres. This auxilliary digs deeper into the many new aesthetic; for ways to make music adequate to a world faces of the toy piano and introduces the fiendish dactylion. transformed by disorientating technologies. Curated by Chris Cutler 01. Playlist 00:00 Gregorio Paniagua, ‘Anakrousis’, 1978 PDF Contents: 01. Playlist 00:04 Margaret Leng Tan, ‘Ladies First Interview’ (excerpt), date unknown 02. Notes Pianist Margaret Leng Tan was born in Singapore, where as a gifted student she 03. Links won a scholarship to study at the Julliard School in New York. In 1981 she met 04. Credits and acknowledgments John Cage and worked with him then until his death in 1992. -

Wolfson Long Composer

David Wolfson is a composer, music director, arranger, and pianist who lives in New York City, currently a PhD candidate in composition at Rutgers University. He holds an MA in composition from Hunter College, where he studied with Shafer Mahoney and Richard Burke, and a BM from the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he studied with Eugene O'Brien and John Rinehart, graduating in 1985. In that same year he was awarded the first annual Darius Milhaud Award by the Darius Milhaud Society and won the Bascom Little Musical Theatre Composition Competition for his short opera, Rainwait. Mr Wolfson’s music has been called “brilliant” by the Cleveland Plain Dealer; the New York Times referred to it as “musically inventive” and “theatrically forceful.” His concert works have been performed by such notable performers as Margaret Leng Tan, Jenny Lin, and the cello quartet Cello. Recent premieres include Ruck, for saxophone quartet, at Marble Collegiate Church in New York City; Twinkle, Dammit!, for toy piano and toys by Margaret Leng Tan at the 1st International Toy Piano Festival; and Rapture, a short opera, on the Pocket Opera series at Hunter College in New York City. A film version of another short opera, Maya’s Ark (produced by Grethe Holby’s Ardea Arts), recently had its premiere screening. Mr. Wolfson is the composer of Story Salad, a series of stage revues for children, which toured nationally for fourteen seasons beginning in 1988, and was seen by well over a million children, teachers and parents. He has supplied incidental music for several off-off-Broadway plays, created sound designs for a set of Macy’s window displays, and written songs for an amusement park big-headed-costumed-character show, Riverside Park’s Country Critter Jamboree. -

A Performer's Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage

A Performer’s Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage: The 1930s to 1950s. A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By Sejeong Jeong B.M., Sookmyung Women’s University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2014 ________________________________ Committee Chair : Jeongwon Joe, Ph. D. ________________________________ Reader : Awadagin K.A. Pratt ________________________________ Reader : Christopher Segall, Ph. D. ABSTRACT John Cage is one of the most prominent American avant-garde composers of the twentieth century. As the first true pioneer of the “prepared piano,” Cage’s works challenge pianists with unconventional performance practices. In addition, his extended compositional techniques, such as chance operation and graphic notation, can be demanding for performers. The purpose of this study is to provide a performer’s guide for four prepared piano works from different points in the composer’s career: Bacchanale (1938), The Perilous Night (1944), 34'46.776" and 31'57.9864" For a Pianist (1954). This document will detail the concept of the prepared piano as defined by Cage and suggest an approach to these prepared piano works from the perspective of a performer. This document will examine Cage’s musical and philosophical influences from the 1930s to 1950s and identify the relationship between his own musical philosophy and prepared piano works. The study will also cover challenges and performance issues of prepared piano and will provide suggestions and solutions through performance interpretations. -

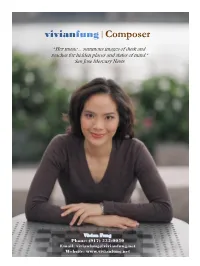

Vivianfung|Composer

vivianfung|Composer “Her music ... summons images of dusk and reaches for hidden places and states of mind.” San Jose Mercury News Vivian Fung Phone: (917) 535-0050 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vivianfung.net Vivian Fung has distinguished herself as a composer with a unique and powerful compositional voice. Since earning her doctorate from The Juilliard School in 2002, she has forged her own approach often merging western forms with non-western vivianfung|Composer influences such as Balinese and Javanese gamelan and folk songs from minority regions of China. The New “…as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the York Times has described her work as ―evocative,‖ Kronos for the first time.” and The Strad hails her Uighur-influenced music to be The Strad ―as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the Kronos for the first time.‖ Chicago Tribune described Fung‘s Yunnan Folk Songs as conveying ―a winning rawness that went beyond exoticism.‖ Fung has traveled extensively for her work. In 2004, she traveled to Bali, Indonesia Highlights of Fung's recent world as part of the Asia Pacific Performance Exchange premieres include: her Violin Concerto for Kristin Program, sponsored by the UCLA Center for Lee and Grammy nominated Metropolis Ensemble, Intercultural Performance. In summer 2010, as an Dust Devils commissioned by the Eastern Music ensemble member of Gamelan Dharma Swara, she Festival celebrating their 50th anniversary, Yunnan completed a performance tour of Bali including Folk Songs by Fulcrum Point New Music Project in competing in the Bali Arts Festival. Chicago; new choral works by the acclaimed Suwon Civic Chorale in South Korea; Chant by pianist Fung‘s works have increasingly Margaret Leng Tan at the Museum of Modern Art in become part of the core repertoire. -

•••I Lil , .1, Llle! E

1114 IEIT liVE FESTIVIL 1994 NEXT WAVE COVEll AND POSTER AR11ST ROBERT MOS1tOwrrz •••I_lil , .1, lllE! II I E 1.lnII ImlEI 14. IS BAMBILL BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President & Executive Producer THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Dennis Russell Davies, Principal Conductor Lukas Foss, Conductor Laureate 41st Season, 1994/95 MIRROR IMAGES in the BAM Opera House October 14, 15, 1994 PRE-CONCERT RECITAL at 7pm PHILIP GLASS Six Etudes Dennis Russell Davies, Piano (American premiere) BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA DENNIS RUSSELL DAVIES, Conductor MARGARET LENG TAN, Piano 8pm JOHN ZORN For Your Eyes Only (BPO Commission) CHEN YI Piano Concerto Margaret Leng Tan, Piano (BPO commission; premiere performance) - Intermission - PHILIP GLASS Symphony No.2 (BPO commission; premiere performance) Allegro Andante Allegro POST-CONCERT DIALOGUE with Chen Yi, Philip Glass, Dennis Russell Davies, and Joseph Horowitz Philip Glass' Symphony No.2 is commissioned by BPO with partial funding provided by the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust. Symphony No.2 composed by Philip Glass. Copyright 1994 Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. THE STANLEY H. KAPLAN EDUCATIONAL CENTER ACOUSTICAL SHELL The Brooklyn Philharmonic and the Brooklyn Academy of Music gratefully acknowledge the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley H. Kaplan, whose assistance made possible the Stanley H. Kaplan Educational Center Acoustic Shell. THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA IS THE RESIDENT ORCHESTRA OF BAM. _ MIRROR IMAGES _ mainly associate£! with opera; ballet. film. and experimentaltheatet~ the opportuni f,r to "think a\Jour tne tradition of &Ythphonic musk;/' Glass haSstateu. openeu "a new world ofmusic--and I am very much looking forward to what I will discover." Glass's Symphony No. -

Nasher's 'Soundings' Offers Rare Performance of Uniquely Corrupted

February 16, 2017 Nasher’s 'Soundings' offers rare performance of uniquely corrupted composition and instrument http://www.dallasnews.com/arts/performing-arts/2017/02/16/nashers-soundings-offers-rare- performance-uniquely-corrupted-composition-instrument By Christopher Mosley American composer John Cage is known as much for what he didn’t do as he is for his completed works. Arguably one of the most important and controversial artists of the last century, Cage’s infamous composition,"4' 33"," directs a musician to sit at the piano in complete silence for exactly four minutes and 33 seconds. This has made his name a shorthand dig at the audacity of academic and experimental music, and a beloved figure to cultural radicals ever since. Music as we know it might be completely unrecognizable, however, were it not for the “prepared piano,” another musical concept that Cage helped to innovate. The prepared piano will be heard at an entry in the Nasher Sculpture Center’s "Soundings" series on Saturday, Feb. 18. Moscow-born pianist Boris Berman will perform "Sonatas and Interludes," composed by Cage, who brought the prepared piano to the greater public consciousness in the late 1940s. Berman is a scholar of Prokofiev who has recorded works by the Russian composer as well as Cage. The concept evolved from techniques employed by musicians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who decided that not even the grand Pianist Boris Berman performs John Cage's "Sonatas and Interludes" as part of the seventh season of "Soundings: New piano was complex enough for their vision and Music at the Nasher." (Oleg Kvashuk, courtesy of the Nasher desires. -

Reading & Listening Guide: John Cage and Experimental Music

John Cage and Experimental Music If asked to name one person who has been the most important influence on avant-garde music in the last half of the 20 th century, our answer unquestionably would be “John Cage.” Cage’s originality and ideas will resonate throughout our entire course. In this lesson we listen to a few pieces that illustrate various stages in his musical development. 1. Read the Wikipedia article about John Cage. You will need information in this article to help answer many of the questions in this lesson. • With what famous composer did Cage study? What vow did Cage make that convinced the composer to give the lessons for free? Why did Cage eventually quit? • Why was his stint at the Cornish School of the Arts in Seattle important to him? What did he accomplish there? What musical instrument did he invent? • What kind of crisis did Cage experience in the mid-1940s? What did he turn to and how did this influence the Sonatas and Interludes , some of which you will listen to for this assignment. • What did Cage discover in the 1950s that had a major influence on his compositional methods? In the early 1950s, what became Cage’s standard tool for composition and how did he use it? • Among other things, Cage composed several “Variations” pieces in the late 1950s and 1960s. The Wikipedia article says that these were in fact “happenings,” an art form that Cage and his students had established earlier. What are happenings? Why are they more than merely musical compositions? • Cages “Experimental Composition” classes in New York inspired the Fluxus movement. -

Piano 1 El Piano

Piano 11 Piano Piano Tesitura Caracter€sticas Clasificaci•n Instrumento de cuerda percutida Instrumento de teclado Instrumentos relacionados Clavec€n, clavicordio, dulc•mele, espineta, ‚rgano Hammond, pianola, piano con pedales Inventor Bartolomeo Cristofori Desarrollado Hacia 1700 M‚sicos ƒƒ PPiiaanniissttaass Fabricantes ƒƒ FaFabrbricicanantetes de pipiananosos Art€culos relacionados ƒƒ CCoommppoossiicciioonneesppaa rrappii aannoo ƒƒ AAcc„„ssttiiccaddeel ppiiaa nnoo ƒƒ AAffiinnaaccii……nddeel ppiiaa nnoo ƒƒ FFrreeccuueenncciiaasdd eaa ffiinnaaccii……ndd eelpp iiaannoo ElEl piano (palabra que en italiano significa †suave‡, y en este caso es ap…cope del t•rmino original, †pianoforte‡, que hac€a referencia a sus matices suave y fuerte) es un instrumento musical clasificado como instrumento de teclado de cuerdas percutidas por el sistema de clasificaci…n tradicional, y seg„n la clasificaci…n de Hornbostel-Sachs es un cord…fono simple. El m„sico que toca el piano recibe el nombre de pianista. Piano 22 Estˆ compuesto por una caja de resonancia, a la que se ha agregado un teclado mediante el cual se percuten las cuerdas de acero con macillos forrados de fieltro, produciendo el sonido. Las vibraciones se transmiten a trav•s de los puentes a la tabla arm…nica, que los amplifica. Estˆ formado por un arpa cromˆtica de cuerdas m„ltiples, accionada por un mecanismo de percusi…n indirecta, a la que se le han a‰adido apagadores. Fue inventado en torno al a‰o 1700 por el paduano Bartolomeo Cristofori. Entre sus antecesores se encuentran instrumentos como la c€tara, el monocordio, el dulc•mele, el clavicordio y el clavec€n. A lo largo de la historia han existido diferentes tipos de pianos, pero los mˆs comunes son el piano de cola y el piano vertical o de pared.