Sinophone Cinemas This Page Intentionally Left Blank Sinophone Cinemas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music

China Perspectives 2020-2 | 2020 Sinophone Musical Worlds (2): The Politics of Chineseness Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music Nathanel Amar Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/10063 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.10063 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2020 Number of pages: 3-6 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Nathanel Amar, “Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music”, China Perspectives [Online], 2020-2 | 2020, Online since 01 June 2020, connection on 06 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/10063 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 10063 © All rights reserved Editorial china perspectives Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music NATHANEL AMAR he first special issue of China Perspectives on “Sinophone Musical itself as a more traditional approach to Chinese-sounding music but was Worlds” (2019/3) laid the theoretical foundation for a musical appropriated by amateur musicians on the Internet who subvert accepted T approach to Sinophone studies (Amar 2019). This first issue notions of Chinese history and masculinity (see Wang Yiwen’s article in this emphasised the importance of a “place-based” analysis of the global issue). Finally, the last article lays out in detail the censorship mechanisms for circulation of artistic creations, promoted in the field of Sinophone studies by music in the PRC, which are more complex and less monolithic than usually Shu-mei Shih (2007), and in cultural studies by Yiu Fai Chow and Jeroen de described, and the ways artists try to circumvent the state’s censorship Kloet (2013) as well as Marc Moskowitz (2010), among others. -

Award-Winning Hong Kong Film Gallants to Premiere at Hong Kong

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Award-winning Hong Kong film Gallants to premiere at Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 in Singapore One-week festival to feature a total of 10 titles including four new and four iconic 1990s Hong Kong films of action and romance comedy genres Singapore, 30 June 2011 – Movie-goers can look forward to a retro spin at the upcoming Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 (HKFF 2011) to be held from 14 to 20 July 2011 at Cathay Cineleisure Orchard. A winner of multiple awards at the Hong Kong Film Awards 2011, Gallants, will premiere at HKFF 2011. The action comedy film will take the audience down the memory lane of classic kung fu movies. Other new Hong Kong films to premiere at the festival include action drama Rebellion, youthful romance Breakup Club and Give Love. They are joined by retrospective titles - Swordsman II, Once Upon A Time in China II, A Chinese Odyssey: Pandora’s Box and All’s Well, Ends Well. Adding variety to the lineup is Quattro Hong Kong I and II, comprising a total of eight short films by renowned Hong Kong and Asian filmmakers commissioned by Brand Hong Kong and produced by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society. The retrospective titles were selected in a voting exercise that took place via Facebook and SMS in May. Public were asked to select from a list of iconic 1990s Hong Kong films that they would like to catch on the big screen again. The list was nominated by three invited panelists, namely Randy Ang, local filmmaker; Wayne Lim, film reviewer for UW magazine; and Kenneth Kong, film reviewer for Radio 100.3. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

The Pop Scene Around the World Andrew Clawson Iowa State University

Volume 2 Article 13 12-2011 The pop scene around the world Andrew Clawson Iowa State University Emily Kudobe Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival Recommended Citation Clawson, Andrew and Kudobe, Emily (2011) "The pop cs ene around the world," Revival Magazine: Vol. 2 , Article 13. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival/vol2/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revival Magazine by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clawson and Kudobe: The pop scene around the world The POP SCENE Around the World Taiwan Hong Kong Japan After the People’s Republic of China was Japan is the second largest music market Hong Kong can be thought of as the Hol- established, much of the music industry in the world. Japanese pop, or J-pop, is lywood of the Far East, with its enormous left for Taiwan. Language restrictions at popular throughout Asia, with artists such film and music industry. Some of Asia’s the time, put in place by the KMT, forbade as Utada Hikaru reaching popularity in most famous actors and actresses come the use of Japanese language and the the United States. Heavy metal is also very from Hong Kong, and many of those ac- native Hokkien and required the use of popular in Japan. Japanese rock bands, tors and actresses are also pop singers. -

Hong Kong Literature As Sinophone Literature = È'¯Èªžèªžç³

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 8 Issue 2 Vol. 8.2 & 9.1 八卷二期及九卷一期 Article 2 (2008) 1-1-2008 Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學 初論 Shu Mei SHIH University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Shih, S.-m. (2008). Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學初論. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 8.2&9.1, 12-18. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Hong Kong Literature as Sinophone Literature 華語語系香港文學初論 史書美 SHIH Shu-mei 加州大學洛杉磯分校亞洲語言文化系、 亞美研究系及比較文學系 Department of Comparative Literature, Asian Languages and Cultures, and Asian American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles A denotative meaning of the term “Sinophone,” as used by Sau-ling Wong in her work on Sinophone Chinese American literature to designate Chinese American literature written in Sinitic languages, is a productive way to start the investigation of the notion in terms of its connotative meanings.1 2 Connotation, by dictionary definition, is the practice that implies other characteristics and meanings beyond the term’s denotative meaning; ideas and feelings invoked in excess of the literal meaning; and, as a philosophical practice, the practice of identifying certain determining principles underlying the implied and invoked meanings, characteristics, ideas, and feelings. This short essay is a preliminary exploration of the connotative meanings of the category that I call Sinophone Hong Kong literature vis-a-vis the emergent field of Sinophone'studies as the study of Sinitic-language cultures, communities, and histories on the margins of China and Chineseness. -

Transitions-Review-1.Pdf

ENCORE > ARTS COUNCIL MALTA WHETHER IT’S A BACH FUGUE, A MOZART SONATA OR A CHOPIN NOCTURNE, THE SCORE IS THE ONLY LINK BETWEEN THE PIANIST AND THE COMPOSER. BUT WHAT IF TODAY’S CONCERT PIANIST COULD ACTUALLY CONSULT THE COMPOSER HIMSELF? FOR PIANIST TRICIA DAWN WILLIAMS, CONVERSING WITH THE COMPOSER IS NOT A SÉANCE WITH THE DEPARTED BECAUSE SHE SPECIALISES IN CONTEMPORARY REPERTOIRE AND IN MOST CASES THE COMPOSER IS ALIVE AND KICKING. THANKS TO ARTS COUNCIL MALTA’S CULTURAL EXPORT FUND, WILLIAMS TRAVELLED TO NEW YORK FOR MASTER CLASSES WITH PIANIST MARGARET LENG TAN; A MUSIC JOURNEY THAT TOOK HER FROM THE PRINTED SCORES TO AN ENCOUNTER WITH AMERICAN COMPOSER GEORGE CRUMB ENCORE > ARTS COUNCIL MALTA In 2015, Tricia Dawn Williams decided to tackle the ground-breaking work Makrokosmos by George Crumb which is divided into two volumes: Volume I SHE HAS was composed in 1972 and Volume II in 1973. This monumental work is unlike any other piece ever PROGRESSIVELY written for the piano. In fact Makrokosmos remains the most comprehensive and influential exploration PERFECTED of the new technical resources of the piano from the twentieth century. One of the major challenges of this work is that it requires the pianist to exercise many AN INDIVIDUAL unorthodox playing practices, like plucking strings inside the piano, playing glissandi across strings, STYLE FUSING sliding a scrape along a string, damping the strings with various objects (like paper, a metal chain, glass) SOUND, as well as whistling tones and vocal utterances. This dazzling exploration of musical timbre is probably the CHOREOGRAPHY most famous aspect of Makrokosmos. -

PROBES #23.2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #23.2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. Auxiliaries PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s conceptual The PROBES Auxiliaries collect materials related to each episode that try to give contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and expose the a broader – and more immediate – impression of the field. They are a scan, not a search for a new sonic language made urgent after the deep listening vehicle; an indication of what further investigation might uncover collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks and, for that reason, most are edited snapshots of longer pieces. We have tried to at the many probes and experiments that were launched in light the corners as well as the central arena, and to not privilege so-called the last century in search of new musical resources, and a serious over so-called popular genres. This auxilliary digs deeper into the many new aesthetic; for ways to make music adequate to a world faces of the toy piano and introduces the fiendish dactylion. transformed by disorientating technologies. Curated by Chris Cutler 01. Playlist 00:00 Gregorio Paniagua, ‘Anakrousis’, 1978 PDF Contents: 01. Playlist 00:04 Margaret Leng Tan, ‘Ladies First Interview’ (excerpt), date unknown 02. Notes Pianist Margaret Leng Tan was born in Singapore, where as a gifted student she 03. Links won a scholarship to study at the Julliard School in New York. In 1981 she met 04. Credits and acknowledgments John Cage and worked with him then until his death in 1992. -

Wolfson Long Composer

David Wolfson is a composer, music director, arranger, and pianist who lives in New York City, currently a PhD candidate in composition at Rutgers University. He holds an MA in composition from Hunter College, where he studied with Shafer Mahoney and Richard Burke, and a BM from the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he studied with Eugene O'Brien and John Rinehart, graduating in 1985. In that same year he was awarded the first annual Darius Milhaud Award by the Darius Milhaud Society and won the Bascom Little Musical Theatre Composition Competition for his short opera, Rainwait. Mr Wolfson’s music has been called “brilliant” by the Cleveland Plain Dealer; the New York Times referred to it as “musically inventive” and “theatrically forceful.” His concert works have been performed by such notable performers as Margaret Leng Tan, Jenny Lin, and the cello quartet Cello. Recent premieres include Ruck, for saxophone quartet, at Marble Collegiate Church in New York City; Twinkle, Dammit!, for toy piano and toys by Margaret Leng Tan at the 1st International Toy Piano Festival; and Rapture, a short opera, on the Pocket Opera series at Hunter College in New York City. A film version of another short opera, Maya’s Ark (produced by Grethe Holby’s Ardea Arts), recently had its premiere screening. Mr. Wolfson is the composer of Story Salad, a series of stage revues for children, which toured nationally for fourteen seasons beginning in 1988, and was seen by well over a million children, teachers and parents. He has supplied incidental music for several off-off-Broadway plays, created sound designs for a set of Macy’s window displays, and written songs for an amusement park big-headed-costumed-character show, Riverside Park’s Country Critter Jamboree. -

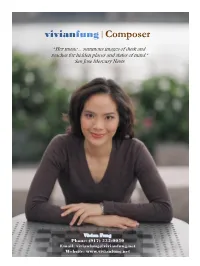

Vivianfung|Composer

vivianfung|Composer “Her music ... summons images of dusk and reaches for hidden places and states of mind.” San Jose Mercury News Vivian Fung Phone: (917) 535-0050 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vivianfung.net Vivian Fung has distinguished herself as a composer with a unique and powerful compositional voice. Since earning her doctorate from The Juilliard School in 2002, she has forged her own approach often merging western forms with non-western vivianfung|Composer influences such as Balinese and Javanese gamelan and folk songs from minority regions of China. The New “…as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the York Times has described her work as ―evocative,‖ Kronos for the first time.” and The Strad hails her Uighur-influenced music to be The Strad ―as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the Kronos for the first time.‖ Chicago Tribune described Fung‘s Yunnan Folk Songs as conveying ―a winning rawness that went beyond exoticism.‖ Fung has traveled extensively for her work. In 2004, she traveled to Bali, Indonesia Highlights of Fung's recent world as part of the Asia Pacific Performance Exchange premieres include: her Violin Concerto for Kristin Program, sponsored by the UCLA Center for Lee and Grammy nominated Metropolis Ensemble, Intercultural Performance. In summer 2010, as an Dust Devils commissioned by the Eastern Music ensemble member of Gamelan Dharma Swara, she Festival celebrating their 50th anniversary, Yunnan completed a performance tour of Bali including Folk Songs by Fulcrum Point New Music Project in competing in the Bali Arts Festival. Chicago; new choral works by the acclaimed Suwon Civic Chorale in South Korea; Chant by pianist Fung‘s works have increasingly Margaret Leng Tan at the Museum of Modern Art in become part of the core repertoire. -

•••I Lil , .1, Llle! E

1114 IEIT liVE FESTIVIL 1994 NEXT WAVE COVEll AND POSTER AR11ST ROBERT MOS1tOwrrz •••I_lil , .1, lllE! II I E 1.lnII ImlEI 14. IS BAMBILL BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President & Executive Producer THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Dennis Russell Davies, Principal Conductor Lukas Foss, Conductor Laureate 41st Season, 1994/95 MIRROR IMAGES in the BAM Opera House October 14, 15, 1994 PRE-CONCERT RECITAL at 7pm PHILIP GLASS Six Etudes Dennis Russell Davies, Piano (American premiere) BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA DENNIS RUSSELL DAVIES, Conductor MARGARET LENG TAN, Piano 8pm JOHN ZORN For Your Eyes Only (BPO Commission) CHEN YI Piano Concerto Margaret Leng Tan, Piano (BPO commission; premiere performance) - Intermission - PHILIP GLASS Symphony No.2 (BPO commission; premiere performance) Allegro Andante Allegro POST-CONCERT DIALOGUE with Chen Yi, Philip Glass, Dennis Russell Davies, and Joseph Horowitz Philip Glass' Symphony No.2 is commissioned by BPO with partial funding provided by the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust. Symphony No.2 composed by Philip Glass. Copyright 1994 Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. THE STANLEY H. KAPLAN EDUCATIONAL CENTER ACOUSTICAL SHELL The Brooklyn Philharmonic and the Brooklyn Academy of Music gratefully acknowledge the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley H. Kaplan, whose assistance made possible the Stanley H. Kaplan Educational Center Acoustic Shell. THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA IS THE RESIDENT ORCHESTRA OF BAM. _ MIRROR IMAGES _ mainly associate£! with opera; ballet. film. and experimentaltheatet~ the opportuni f,r to "think a\Jour tne tradition of &Ythphonic musk;/' Glass haSstateu. openeu "a new world ofmusic--and I am very much looking forward to what I will discover." Glass's Symphony No. -

免於遭受性侵犯 to Protect Youngsters Under 18 from Sexual Abuse 目錄 Table of Contents

保護18歲以下人士 免於遭受性侵犯 To protect youngsters under 18 from sexual abuse 目錄 Table of contents 使命 Mission 0 會長的話 President’s Message 2 主席的話 Chairman’s Message 3 2017-2018年度執行委員會會議 Board Meetings 2017-2018 4 執行委員會名單 List of the Board of Governors 5 小組委員會名單 List of Committees 6 活動報告 Program Report 8 衷心感謝 Note of Thanks 34 收入與支出 Income & Expenditure 40 鳴謝 Acknowledgements 42 『二十年,全憑大家的熱誠支持,《護苗基金》方能存活至今。 即使叩頭千萬次謝你,也謝不完……』 感激莫名的 芳芳 “For 20 years your unwavering support has made it possible for us to strive on. To kowtow a million times would not be enough to thank you…” Gratefully yours, Fong Fong 2 主席的話 Chairman’s Message This year marks the 20th Anniversary of our Foundation and I am pleased to report that we continue to strike at all fronts to fight against child sexual abuse (CSA) in our community. Our community engagement programs have taken us to places like Aberdeen and Sham Shui Po. It is encouraging to find that members of the public, from grandmothers to small children, are now much better informed about CSA. Our education programs have been much valued by schools as a vital part of sex education. Not resting on our laurels, we have constantly 今年是護苗基金的20周年,我們仍然致力在不同 improved our educational materials by reviewing 領域進行保護兒童的工作。 feedback and undertaking research and studies. 我們的社區參與計劃已將護苗基金帶到香港仔和深水埗 等地區。最令人鼓舞的是市民大眾,不論年齡,對兒童 Our equally important work includes offering a 性侵犯的問題有更多的認識。 “Hugline”service; making the public more informed about CSA through the media; and conveying our 許多學校已把我們的教育課程視為性教育的重要一環, views on tackling CSA problems to the government. 但我們不會故步自封,並將繼續進行評估和研究, 改善我們的教材。 Hopefully one day our work will become redundant 我們其他重要的工作亦包括《護苗線》服務;讓公眾 when CSA is no longer a problem. -

Queer Sinophone Cultures

Queer Sinophone Cultures Edited by Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich Routledge II Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2014 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich The right of the editors to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Queer Sinophone Cultures / edited by Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich. pages cm. – (Routledge Contemporary China Series ; 107) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-415-62294-3 (hardback : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-0-203- 59092-8 (e-book) 1. Chinese diaspora. 2. Gays in literature. 3. Gender identity–China. 4. Chinese–Foreign countries–Ethnic identity.