Women's Involvement in Conflict Early Warning Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict Resolution – the Philippines Experience

Conflict Resolution – The Philippines Experience A Comparative Study Visit Report 20th – 27th June 2015 Published by Democratic Progress Institute 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] +44 (0)203 206 9939 First published, 2015 ISBN: © DPI – Democratic Progress Institute, 2015 DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable 2 Conflict Resolution – The Philippines Experience Contents Saturday 20th June – Arrive in Manila and Welcome Dinner .....5 Sunday 21st June – DPI Welcome Roundtable Meeting .............6 Monday 22nd June - Roundtable Meeting: The Role of International Contact Groups in Conflict Resolution ...............16 Monday 22nd June - Roundtable Meeting: An Overview of the Philippine Peace Process with the Office of the Presidential Advisor on the Peace Process ....................................................48 Tuesday 23rd June - Private Tour of the House of Representatives .....................................................................67 Tuesday 23rd June - Roundtable Meeting: The Role of Media in Conflict Resolution ..................................................................70 -

Weaving Peace in Mindanao:Strong Advocacy Through Collective Action

Weaving Peace in Mindanao:Strong Advocacy through Collective Action WEAVING PEACE IN MINDANAO: Strong Advocacy through Collective Action A collective impact case study on the Mindanao Peaceweavers network Michelle Garred May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 4 Executive Summary 5 I. Methodology and Limitations 6 II. Regional Context 8 III. Overview of Mindanao Peaceweavers 10 Structure 10 Founding 10 Stages of action 11 Key contributions 12 IV. Conditions for Collective Impact 13 Collective and emergent understanding of the context 13 Collective intention and action 14 Collective learning and adaptation 15 Continuous communication and accountability 15 Support structure or backbone 15 Other collective impact themes 16 Difficulties and barriers 18 V. Summary of Success Factors and Challenges 21 Key success factors 21 Key challenges 22 Multitier networks 22 VI. Future Considerations for Mindanao Peaceweavers 23 Annexes Annex A: Participants in Interviews & Focus Group Discussions 24 Annex B: Sample Guide Questions for Interviews and Focus Group Discussions 26 Figures A: Map of the Philippines, with Mindanao at south 8 B: Map of Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (current) 9 C: Development of the Peoples’ Agenda 13 D: Action Points of the Peoples’ Agenda 14 E: Campaign Spotlight — Mamasapano and All Out Peace 18 2 Acronyms BBL — Bangsamoro Basic Law BISDAK - Genuine Visayans for Peace CDA — CDA Collaborative Learning Projects CRS — Catholic Relief Services GPPAC — Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict GRP — Government of the Republic of the Philippines IID — Initiatives for International Dialogue MILF — Moro Islamic Liberation Front MPPA — Mindanao Peoples’ Peace Agenda MPW — Mindanao Peaceweavers Acknowledgments CDA specially thanks Initiatives for International Dialogue for its in-country support, which proved essential to writing this case study. -

D:\Working Folder\Bantay Ceasef

BANTAY CEASEFIRE Mindanao Grassroots Ceasefire Review and Assessment January 6-12 & 18-19, 2003 Cotabato, Maguindanao, Lanao & Sultan Kudarat CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4 COTABATO 10 LANAO 17 MAGUINDANAO 25 SULTAN KUDARAT 31 LOBBY MISSION IN MANILA 34 C O N V E N O R S : Consortium of Bangsamoro Civil Society Mindanao Peace Advocates Conference Initiatives for International Dialogue Mindanao Coalition of Development NGOs Sumpay-Mindanao Balay Balik-Kalipay Mindanao Peoples Peace Movement LAFFCOD, Inc. Muslim Multi-sectoral Movement for Peace and Development Maranao Peoples Development Center United Youth of the Philippines Pikit Parish Freedom from Debt Coalition FOR MORE INFORMATION: Mindanao Peoples’ Caucus (MPC) Secretariat Telefax: (63) (82) 2992052 Tel: (63) (82) 2992574 to 75 E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION From January 6-12 & 18-19, 2003 the “Bantay Ceasefire” led an investigative mission into Maguindanao, Lanao, Sultan Kudarat and Cotabato. The mission was prompted by, first, the reported violations of the ceasefire in these areas; and second, the apparent failure of the GRP-MILF peace talks to develop an effective monitoring mechanism for the ceasefire. The success of future peace talks rests largely on mutual confidence and trust between the two parties to observe previous agreements. Thus, a secure environment is a pre-requisite for the impending questions of development, ancestral domain and a politically negotiated settlement. A secure environment is also essential to the thousands that live, -

Delays in the Peace Negotiations Between the Philippine Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front: Causes and Prescriptions Soliman M

No. 3, January 2005 Delays in the Peace Negotiations between the Philippine Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front: Causes and Prescriptions Soliman M. Santos, Jr. East-West Center WORKING PAPERS Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes for the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, corporations and a number of Asia- Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East-West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction in the Asia Pacific region and promoting American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. Contact Information: East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel: (202) 293-3995 Fax: (202) 293-1402 [email protected] Soliman M. Santos, Jr. is a Filipino human rights lawyer, peace advocate, and legal scholar, who is a Peace Fellow at the Gaston Z. Ortigas Peace Institute East-West Center Washington Working Papers This publication is a product of the East-West Center Washington’s Project on Internal Conflicts. -

Wo M En C O U

“All peace and security advocates – both individually and as part of organizational work - should read the 2012 civil society monitoring report on Resolution 1325! It guides us to where we should focus our energies and resources to ensure women’s equal participation in all peace processes and at all decision- making levels, thereby achieving sustainable peace.” -Ambassador Anwarul K. Chowdhury, Former Under- Secretary-General and High Representative of the United Nations “The GNWP initiative on civil society monitoring of UNSCR 1325 provides important data and analysis Security Council Resolution 1325: Security Council Resolution WOMEN COUNT WOMEN COUNT on the implementation of the resolution at both the national and local levels. It highlights examples of what has been achieved, and provides a great opportunity to reflect on how these achievements can Security Council Resolution 1325: be further applied nationwide. In this regard my Ministry is excited to be working with GNWP and its members in Sierra Leone on the Localization of UNSCR 1325 and 1820 initiatives!” - Honorable Steve Gaojia, Minister of Social Welfare, Gender & Children’s Affairs, Government of Sierra Leone Civil Society Monitoring Report 2012 “The 2012 Women Count: Security Council Resolution 1325 Civil Society Monitoring Report uses locally acceptable and applicable indicators to assess progress in the implementation of Resolution 1325 at the country and community levels. The findings and recommendations compel us to reflect on what has been achieved thus far and strategize on making the implementation a reality in places that matters. Congratulations to GNWP-ICAN on this outstanding initiative!” - Leymah Gbowee, 2011 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate “The civil society monitoring report on UNSCR 1325 presents concrete data and analysis on Civil Society 2012 Report Monitoring the implementation of the resolution at national level. -

Primed and Purposeful

South-South Network for Non-State Armed Group Engagement By Soliman M. Santos, Jr. and Paz Verdades M. Santos 18 Mariposa St., Cubao, 1109 Quezon City, Philippines with Octavio A. Dinampo, Herman Joseph S. Kraft, PURPOSEFUL PRIMED AND p +632 7252153 Artha Kira R. Paredes, and Raymund Jose G. Quilop e [email protected] Edited by Diana Rodriguez w www.southsouthnetwork.com Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland PRIMED AND PURPOSEFUL p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 ARMED GROUPS AND HUMAN SECURITY EFFORTS e [email protected] IN THE PHILIPPINES w www.smallarmssurvey.org Soliman M. Santos, Jr. and Paz Verdades M. Santos and Paz Verdades Soliman M. Santos, Jr. Primed and Purposeful: Armed Groups and Human Security Efforts in the Philippines pro- vides the political and historical detail necessary to understand the motivations and probable outcomes of conflicts in the country. The volume explores related human security issues, including the willingness of several Filipino armed groups to negotiate political settlements to the conflicts, and to contemplate the demobilization and reintegration of combatants into civilian life. Light is also shed on the use of small arms—the weapons of choice for armed groups—whose availability is maintained through leakage from government arsenals, porous borders, a thriving domestic craft industry, and a lax regulatory regime. —David Petrasek, Author, Ends and Means: Human Rights Approaches to Armed Groups (International Council on Human Rights Policy, 2000) At the centre of this book are the ‘primed and purposeful’ protagonists of the Philippines’ two major internal armed conflicts: the nationwide Communist insurgency and the Moro insurgency in the Muslim part of Mindanao. -

Survivors of Air Force Bombing Said No Rebels in Area

Vol. 3 No. 9 September 2008 Peace Monitor Survivors of Air Force bombing said no rebels in area DATU PIANG, Maguindanao, Philippines—It was as if they were racing against each other, rowing their bancas across the Bugok River to get to the village of Butilen. And when they were about 500 meters from Butilen, the bombs fell. When the aerial attack ended, six persons, including two children and a pregnant woman, were dead. Ameen Abdullah, 40, a resident of Butilen, said residents of the village of Tee fled the moment they saw Air Force planes and helicopters hovering overhead on Monday morning. Abdullah said there was no fighting between government troops and Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels when the bombing happened. He said as the planes and helicopters flew over at around 8 a.m., government soldiers arrived, prompting [SURVIVORS/p.11] WAR VICTIMS --- Without any viand, displaced Moro children eat rice at a makeshift relief shelter in the town Murad: “We will never re- proper of Datu Piang, Maguindanao.[] negotiate MOA-AD:” Chief Justice calls for end Esperon: MOA-AD will be to Mindanao fighting “major reference” MAGUINDANAO (MindaNews/14 Sept) – On Thurs- CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY, Philippines — Chief day, the day President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo told a Justice Reynato Puno on Saturday joined calls for an lobby group from Mindanao that government will no end to the fighting between the military and the Moro longer sign the initialed Memorandum of Agreement on Islamic Liberation Front, saying civilians have been Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) with the Moro Islamic Lib- suffering. -

MILF on Dead MOA-AD COTABATO CITY (Oct

Vol. 3 No. 10 October 2008 Peace Monitor MILF on dead MOA-AD COTABATO CITY (Oct. 15) – The Moro Islamic Liberation Front today said it will not launch an uprising in reaction to the Supreme Court’s having dismissed as “unconstitutional” the memorandum of agreement on ancestral domain. “Our forces will remain in a defensive posture. We will not launch any offensive as a consequence of that Supreme Court ruling,” Eid Kabalu, the MILF’s spokesman, said. Kabalu said the MILF is not closed to a peaceful option in resolving the Mindanao conflict. “That is what I can guarantee,” Kabalu said. “The MILF will never fire the first shot that can spark trouble in Mindanao.” Both Kabalu and the MILF’s chief negotiator, Muhaquer Iqbal, said since they do not recognize the Supreme Court, the front is not bound by its ruling on the MOA-AD. “We have not changed our position on the MOA-AD. DIFFICULT SITUATION --- An old Maguindanaon woman, traumatized by war, lies at an evacuation center in [MILF/p.10] Mamasapano, Maguindanao. EU grants P470-M aid for Mindanao peace process Mindanao, pushes peace talks COTABATO CITY (Oct.15) — Japan is optimistic the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Financial support for the civilian victims of Front will resume with the stalled GRP-MILF talks and atrocities in Mindanao continue to pour in as the peacefully resolve the nagging security problems in the European Commission allotted at least R470 million South. in immediate aid and longterm rehabilitation Harumi Kitabayashi, deputy resident representative assistance to the Mindanao Trust Fund (MTF). -

Fourth Public Report, March 2016 to June 2017

TPMT 28 July 2017 Third Party Monitoring Team Fourth Public Report, March 2016 to June 2017 1) Summary In line with the terms of reference of the Third Party Monitoring Team, this fourth public report is intended to provide an overall assessment of developments in the implementation of the Agreements between the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The period of transition from the administration of President Benigno S. Aquino III to that of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte , now marking a year in office, has seen some continuity but also change in the roadmap for implementation of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. Despite the failure of the 16th Congress to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law, the parties in May 29-30, 2016 met in Kuala Lumpur and signed a “Declaration of the Continuity of the Partnership of the GPH and MILF in the Bangsamoro Peace Process”. The first year under the new administration began with optimism for peace as President Duterte had reiterated his campaign promise to bring peace to Mindanao and support the BBL. The following are the main developments during this year: - a new roadmap was put forward by the Philippine government, and agreed by the MILF, that proscribed a “Two Simultaneous Tracks: Federalism + Enabling Law Approach,” where an expanded Bangsamoro Transition Commission would work to draft an “Enabling Law” and also propose constitutional amendments to be taken up during a change to federalism. Subsequent discussions affirmed the MILF position that the -

Towards a Mindanao Peoples' Peace Agenda

Towards A Mindanao Peoples’ Peace Agenda © Initiatives for International Dialogue, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the Philippines Lay-out and photos by Toto Lozano except for pages 4, 6, 8, 12, 14 , 30, 32 and cover IID photo-bank. “The views and opinions reflected in the Mindanao Peoples’ Peace Agenda (MPPA) are those of the Mindanao Peaceweavers (MPW) network members and constituents who participated in the MPPA process and do not necessarily reflect those of its partners, supporters or donors.” n May 2003 a watershed undertaking for peace took-off in Mindanao. Around 300 peace advocates from Mindanao representing at least seven peace networks converged in Davao City Iand established the Mindanao Peace Weavers (MPW). Founded during the “Peace in MindaNOW Conference”, the seven peace networks, namely: Agong Network, Consortium of Bangsamoro Civil Society (CBCS), Inter-Religious Solidarity Movement for Peace (IRSMP), Mindanao Peace Advocates (MPAC), Mindanao Peoples’ Caucus (MPC), Mindanao Peoples Peace Movement (MPPM) and the Mindanao Solidarity Network (MSN), coalesced in the spirit of cooperation, complementation and concerted action towards a common advocacy peace platform. MPW was conceived at a time when there was a compelling need for civil society in Mindanao to unify on a ceasefire call amidst an escalation of armed conflict between government forces and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Since then, MPW has launched joint coordinated campaigns, peace advocacy, and lobby work, bringing in a host of issues that revolved around conflict prevention, peace-building, culture of peace and conflict resolution/management. -

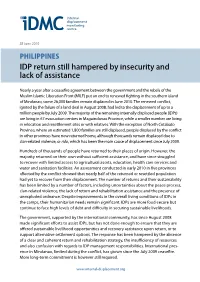

IDP Return Still Hampered by Insecurity and Lack of Assistance

28 June 2010 PHILIPPINES IDP return still hampered by insecurity and lack of assistance Nearly a year after a ceasefire agreement between the government and the rebels of the Muslim Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) put an end to renewed fighting in the southern island of Mindanao, some 26,000 families remain displaced in June 2010. The renewed conflict, ignited by the failure of a land deal in August 2008, had led to the displacement of up to a million people by July 2009. The majority of the remaining internally displaced people (IDPs) are living in 67 evacuation centres in Maguindanao Province, while a smaller number are living in relocation and resettlement sites or with relatives. With the exception of North Cotabato Province, where an estimated 1,800 families are still displaced, people displaced by the conflict in other provinces have now returned home, although thousands remain displaced due to clan-related violence, or rido, which has been the main cause of displacement since July 2009. Hundreds of thousands of people have returned to their places of origin. However, the majority returned on their own without sufficient assistance, and have since struggled to recover with limited access to agricultural assets, education, health care services and water and sanitation facilities. An assessment conducted in early 2010 in five provinces affected by the conflict showed that nearly half of the returned or resettled population had yet to recover from their displacement. The number of returns and their sustainability has been limited by a number of factors, including uncertainties about the peace process, clan-related violence, the lack of return and rehabilitation assistance and the presence of unexploded ordnance. -

The Philippines: Indigenous Rights and the Milf Peace Process

THE PHILIPPINES: INDIGENOUS RIGHTS AND THE MILF PEACE PROCESS Asia Report N°213 – 22 November 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. WHY DO THE LUMAD MATTER? .............................................................................. 1 II. INVOLVEMENT IN THE PEACE PROCESSES ......................................................... 4 A. THE LUMAD AND THE BANGSAMORO CAUSE ............................................................................... 4 B. THE LUMAD, THE MILF AND THE MOA-AD ............................................................................... 5 C. CONSULTATIONS IN 2010-2011 ................................................................................................... 7 III. THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR INDIGENOUS RIGHTS .................................... 8 IV. THE TEDURAY: INDIGENOUS RIGHTS IN THE ARMM .................................... 11 A. WHO ARE THE TEDURAY? ......................................................................................................... 11 B. TEDURAY MOBILISATION .......................................................................................................... 11 V. THE ERUMANEN-MENUVU IN NORTH COTABATO .......................................... 13 A. WHO ARE THE ERUMANEN-MENUVU? ....................................................................................... 13 B. CONFLICT ERUPTS IN SNAKE FISH ............................................................................................