How Vocal Classification Affects Young Singers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

The Singing Telegram

THE SINGING TELEGRAM Happy almost New Year! Well, New Year from the perspective of LOON’s season, at any rate! As we close out this season with the fun and shimmer of our Summer Sparkler, we reflect back on the year while we also look forward to the season to come. Thanks to all who made Don Giovanni such a success! Host families, yard sign posters, volunteer painters, stitchers, poster-hangers, ushers, and donors are a part of the success of any production, right along with the singers, designers, orchestra, and tech crew. Thanks to ALL for bringing this imaginative and engaging produc- tion to the stage! photos by: Michelle Sangster IT’S THE ROOKIE HUDDLE! offered to a singer who can’t/shouldn’t sing a certain role. What The Fach?! Let’s break that down a little more! Character What if we told you that SOPRANO, ALTO, TENOR, BASS Opera is all about telling stories. Sets, costumes, and lights is just the beginning of the types of voices wandering this give us information about time and place. The narrative planet. There are SO MANY VOICES! In this installation of and emotional details of the story are found in the music the Rookie Huddle we’ll talk about how opera singers – and as interpreted by the orchestra and singers. The singers are the people who hire them – rely on a system of transformed with wigs, makeup, and costumes, but their classification called Fach, which breaks those categories into characters are really found in the voice. many more specific parts. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

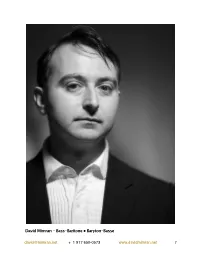

Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 1 100 Words Bio

David Mimran - Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 www.davidmimran.net 1 100 words bio Bass-Baritone David Mimran set aside a career as a lawyer in Paris to sing opera in New York. Great vocal flexibility in a wide tessitura, natural acting skills and a knowledge of nine languages including Italian, French, German, English, Spanish and Finnish allow for a large variety of repertoire. Roles on stage include Alcindoro/Benoît in Bohème, Conte Ceprano in Rigoletto, Niejus & Cascada in Merry Widow, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte, Figaro & Antonio in Le nozze di Figaro, Morales & Zuniga in Carmen, Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Frank in Fledermaus, Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi, Achille in Giulio Cesare and Melisso in Alcina. Languages French: Mother tongue English: Bilingual German, Italian, Spanish: Proficient Finnish, Portuguese, Hebrew: Working knowledge Russian, Hungarian: Basic phonetic reading knowledge I would consider studying a new language to sing a role. Stage Experience Full roles performed • Benoît/Alcindoro in Bohème - Opera Company of Brooklyn • Sciarrone/Jailer in Tosca - Regina Opera • Yakuside in Madama Butterfly - Bleecker Street Opera • Niejus and Cascada in The Merry Widow - Amore Opera • Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte - NY Lyric Opera Theater • Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia - Bleecker Street Opera • Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Spinelloccio/Nicolao in Gianni Schicchi - Regina Opera • Achilla in Giulio Cesare - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Docteur -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Voice Types Are Soprano, Mezzo Soprano, Tenor and Baritone

The four most common voice types are Soprano, Mezzo Soprano, Tenor and Baritone. FEMALE VOCAL RANGE RANGE FEMALE EXAMPLES Highest Soprano Coloratura Soprano Lucia in Lucia di Lammermoor Lyric Soprano Violetta in La Traviata Dramatic Soprano Leonara in Il Trovatore Mezzo Soprano Coloratura Mezzo Rosina in The Barber of Seville Dramatic Mezzo Carmen in Carmen Lowest Contralto Katisha in The Mikado VOICE SOPRANO The highest of the female voice types, the soprano has always had a TYPES place of importance in the order of vocal types. In the operatic world, the soprano is almost always the ‘heroine’ or leading character within an opera. MEZZO SOPRANO The mezzo is the lower-ranged female voice type. Throughout opera history the mezzo has been used to convey many different types of characters: everything from boys or young men (these are called trouser or pants roles), to mother-types, witches, gypsies and old women. The four most common voice types are Soprano, Mezzo Soprano, Tenor and Baritone. MALE VOCAL RANGE RANGE MALE EXAMPLES Highest Tenor Light Lyric Tenor Nemorino in La Cenerentola Lyric Tenor Nadir in the Pearlfishers Lyric-dramatic Tenor Rodolfo in La Boheme Dramatic Tenor Canio in Pagliacci Heldentenor Tristan in Tristan und Isolde Baritone Papageno in The Magic Flute Bass-baritone Figaro in The Magic of Figaro VOICE Lowest Bass Sarastro in The Magic Flute TENOR The Tenor is the highest of the male voices and has many sub categories TYPES such as a lyric tenor and a dramatic tenor. The tenor is usually cast in the romantic roles of opera. -

Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer

What the Fach? Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer Loraine Sims, DMA, Associate Professor, Edith Killgore Kirkpatrick Professor of Voice, LSU 2018 NATS National Conference Las Vegas Introduction One size does not fit all! Trans Singers are individuals. There are several options for the singing voice. Trans woman (AMAB, MtF, M2F, or trans feminine) may prefer she/her/hers o May sing with baritone or tenor voice (with or without voice dysphoria) o May sing head voice and label as soprano or mezzo Trans man (AFAB, FtM, F2M, or trans masculine) may prefer he/him/his o No Testosterone – Probably sings mezzo soprano or soprano (with or without voice dysphoria) o After Testosterone – May sing tenor or baritone or countertenor Third Gender or Gender Fluid (Non-binary or Genderqueer) – prefers non-binary pronouns they/them/their or something else (You must ask!) o May sing with any voice type (with or without voice dysphoria) Creating a Gender Neutral Learning Environment Gender and sex are not synonymous terms. Cisgender means that your assigned sex at birth is in agreement with your internal feeling about your own gender. Transgender means that there is disagreement between the sex you were assigned at birth and your internal gender identity. There is also a difference between your gender identity and your gender expression. Many other terms fall under the trans umbrella: Non-binary, gender fluid, genderqueer, and agender, etc. Remember that pronouns matter. Never assume. The best way to know what pronouns someone prefers for themselves is to ask. In addition to she/her/hers and he/him/his, it is perfectly acceptable to use they/them/their for a single individual if that is what they prefer. -

VB3 / A/ O,(S0-02

/VB3 / A/ O,(s0-02 A SURVEY OF THE RESEARCH LITERATURE ON THE FEMALE HIGH VOICE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Roberta M. Stephen, B. Mus., A. Mus., A.R.C.T. Denton, Texas December, 1988 Stephen, Roberta M., Survey of the Research Literature on the Female High Voice. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1988, 161 pp., 11 tables, 13 illustrations, 1 appendix, bibliography, partially annotated, 136 titles. The location of the available research literature and its relationship to the pedagogy of the female high voice is the subject of this thesis. The nature and pedagogy of the female high voice are described in the first four chapters. The next two chapters discuss maintenance of the voice in conventional and experimental repertoire. Chapter seven is a summary of all the pedagogy. The last chapter is a comparison of the nature and the pedagogy of the female high voice with recommended areas for further research. For instance, more information is needed to understand the acoustic factors of vibrato, singer's formant, and high energy levels in the female high voice. PREFACE The purpose of this thesis is to collect research about the female high voice and to assemble the pedagogy. The science and the pedagogy will be compared to show how the two subjects conform, where there is controversy, and where more research is needed. Information about the female high voice is scattered in various periodicals and books; it is not easily found.