Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scahier 74 Classicisme: Vredestempel, Prinsenhof, Haarlem

74 JAARGANG 23 n SEPTEMBER 2008 ClassicismeSC74.indd 2-3 14-9-2008 18:28:18 Vr e d e s ahier tempel PDF-versie Haarlem jaargang 23 1648 nummer 74 n september 2008 Classicisme verklaard aan de SCahier is sinds septem- ber 1985 een ongeregeld hand van een fietsenhok verschijnend schrift met essays, achtergronden, In 1648 werd in Haarlem op het Prinsenhof meningen en feiten over een Vredestempel gebouwd in een voor die tijd architectuur. Het is bedoeld uiterst moderne bouwstijl: het classicisme. Zo'n om de relaties van Ar- Vredestempel veertig jaar geleden werd dit vergeten prieeltje nog chitext op de hoogte te Sinds 1648 staat op het Haarlemse gebruikt als fietsenhok. houden over de fondslijst, Prinsenhof een ‘tempeltje’ gewijd Dit SCahier beschrijft uitvoerig de achtergronden de architectuurreizen en aan de Vrede van Munster. De van dit kleine bouwkundige sieraad. En passant Architectuurradio. achtergronden van een classicistisch wordt zo geschetst wat classicisme is en hoe het unicum. in de Republiek der Nederlanden ingang vond. Uitgeverij Architext Dat dit verhaal een sterk Haarlems karakter Klein Heiligland 91 Eerder verschenen: draagt, is niet toevallig: Haarlemmers speelden 2011 EE Haarlem SCahier 73 PDF over Retranchement (22 pagina’s), een vooraanstaande rol bij de introductie van e-post: [email protected] te importeren via www.architext.nl. de beginselen van de klassieke oudheid in het www.architext.nl bouwen. eindredactie: Ids Haagsma Inhoud: vormgeving: de IJsgarage s Haarlem Rob van Westreenen De tijd – pagina 5 © 2008 s Architext De plek – pagina 6 De maker (1) – pagina 11 De stijl – pagina 17 De Maker (2) – pagina 23 Het binnen – pagina 28 Rechts: de Vredestempel als fietsenhok, in de vorige jaren zestig. -

Enemy, Rival, Frog

Enemy, Rival, Frog The influence of history on the portrayal of the Dutch in late seventeenth- century English literature BA Thesis Anna Zweers Supervisor: Dr. M. Corporaal Date: 15 June, 2017 Zweers - 1 Abstract: This thesis will look at the way the Dutch are represented in English literature from the Restoration in 1660, taking 1672 as a turning point and looking at texts up to 1685. The focus will be on war, trade and gender, and how Dutch people are portrayed with regards to these three areas. It argues that trade is a theme that is present in all texts written about the Dutch, while the other two themes depend on the subject of the texts. Keywords: seventeenth century, Anglo-Dutch relations, English literature, war, trade, gender Zweers - 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1 – Historical background .......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 – War & Trade since Restoration .................................................................................................. 7 1.3 – 1672 – 1674 ................................................................................................................................ 9 1.4 – After 1672: War & Trade ........................................................................................................ -

Jesper Just Biography

JESPER JUST BIOGRAPHY Jesper Just Born in 1974 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Lives and works in New York EDUCATION 1997-2003 The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. REPRESENTED BY Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris James Cohan Gallery, New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 ––– This Nameless Spectacle, MAC/VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine, France A Vicious Undertow, Single-Chanel Series, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA, USA John Curtin Gallery, Perth, Australia This Nameless Spectacle, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK Photo Spring, Beijing, China MAP, Mobile Art Production, Stockholm, Sweden Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, Montréal, Canada 2010 ––– ARTscape: Denmark – Jesper Just, Galerija VARTAI, Vilnius, Lithuania Jesper Just: Romantic Delusions, Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, FL, USA 2009 ––– Invitation to Love, Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, Norway Jesper Just, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão - Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal Tromsø Gallery of Contemporary Art, Norway 2008 ––– Romantic Delusions, Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris, France Romantic Delusions, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, NY, USA Romantic Delusions, U-turn / Kunsthallen Nikolaj, Copenhagen, Denmark A Voyage in Dwelling, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, England Jesper Just, La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain 2007 ––– A Vicious Undertow, Perry Rubenstein Gallery, New York Jesper Just, Kunsthalle Wien (Museumsquartier), Vienna Jesper Just, SMAK Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Gent Belgium Jesper Just, Witte de With Center -

1.1. the Dutch Republic

Cover Page The following handle holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation: http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61008 Author: Tol, J.J.S. van den Title: Lobbying in Company: Mechanisms of political decision-making and economic interests in the history of Dutch Brazil, 1621-1656 Issue Date: 2018-03-20 1. LOBBYING FOR THE CREATION OF THE WIC The Dutch Republic originated from a civl war, masked as a war for independence from the King of Spain, between 1568 and 1648. This Eighty Years’ War united the seven provinces in the northern Low Countries, but the young republic was divided on several issues: Was war better than peace for the Republic? Was a republic the best form of government, or should a prince be the head of state? And, what should be the true Protestant form of religion? All these issues came together in struggles for power. Who held power in the Republic, and who had the power to force which decisions? In order to answer these questions, this chapter investigates the governance structure of the Dutch Republic and answers the question what the circumstances were in which the WIC came into being. This is important to understand the rest of this dissertation as it showcases the political context where lobbying occurred. The chapter is complemented by an introduction of the governance structure of the West India Company (WIC) and a brief introduction to the Dutch presence in Brazil. 1.1. THE DUTCH REPUBLIC 1.1.1. The cities Cities were historically important in the Low Countries. Most had acquired city rights as the result of a bargaining process with an overlord. -

2000 Jaargang 99

Robert Hook Hollandd ean : Dutch influenc architecturs hi n eo e Alison Stoesser-Johnston The use of these publications by English architects and arti- Introductie)!! sans and the design of Wollaton Hall were not based on any Dutch classicism was a recent arrival in England when first-hand personal impressio f classicisno Italymn i . Thid ha s Robert Hooke made his first architectural designs in the late emergence th waio t r fo t f Inigeo o Jone s architectsa visis Hi . t 1660s. 'e constructioPrioth o t r f Hugo n h May's Eltham to Italy in 1613-'14 in the entourage of Thomas Howard, 2nd Lodg 1663-'64n i e e firsth , t exampl f Dutceo h classicisn mi Earl of Arundel, his close interest in Roman antiquities and England, classical elements straight from Italy and via Flan- intimate knowledge of Palladio's drawings are most ders had been used in English architecture for nearly a hund- dramatically exemplifie Banquetins hi n di g Hous f 1619-22eo . red years. Initially these had been mainly of a decorative na- Not only, however, has Jones here used Palladian "vocabulary" ture but vvith the construction of Inigo Jones' Banqueting 7 but hè has combined it with the application of Scamozzian House (1619-'21) there was a dramatic change in the way orders, the Composite being superimposed on the lonic. This classicism was adapted to English architecture. Jones drew combination of Palladian elements with Scamozzian also on the examples of Palladio and Scamozzi in his architecture influence beginninge th d f Dutcso h classicism.8 Jones' design using both Palladio's treatise, / quattro libri, personal know- was not only a major innovation in England but it also inspired ledge of his architecture and, in the case of Scamozzi, per- Jaco n Campe s va bfirs hi tn i narchitectura l commission i n sonal contact e applieH . -

Werkstuk Charles Julien; Oranjezaal Van Het Paleis Huis

Voor mijn vader i de inleiding 2 ii de hoofdpersonen 7 iii de meesters 11 Jacob van Campen 11 Constantijn Huygens 11 Salomon de Bray 12 Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert 12 Jacob Jordaens 13 Adriaen Hanneman 13 Theodoor van Thulden 14 Caesar Pietersz. van Everdingen 14 Jan Lievens 15 Christiaen Gillisz. van Couwenbergh 16 de inhoud Gonzales Coques 16 Pieter de Grebber 17 Gerard Hermansz. van Honthorst 18 Pieter Claesz Soutman vi de werken 21 noordwand 22 Frederik Hendrik als heerser over de zeeën. 25 Deel van de triomfstoet met meegevoerd goud en zilver. 27 De Nederlandse maagd biedt Frederik Hendrik het opperbevel aan. 29 Deel van de triomfstoet met offerstier. 31 Dit boek werd speciaal vervaardigd in opdracht van Deel van de triomfstoet met olifant en schilderijen. 33 Simone Rijs voor het vak kunstbeschouwing van de Fontys Hogeschool voor de Kunsten te Tilburg Frederik Hendrik ontvangt de survivantie. 35 Deel van de triomfstoet met geschenken uit de Oost en de West. 37 december mmxii oostwand 39 Vormgeving Charles Julien Frederik Hendrik als triomfator. 41 Drukwerk Reclameland.nl Frederik Hendriks standvastigheid. 43 Bij het samenstellen van dit boek heb ik gebruik gemaakt van de informatie die te vinden is op internet en in boe- Deel van de triomfstoet. Amalia met haar dochters als toeschouwers van de triomf 45 ken/publikaties zoals aangegeven achterin het boek. Frederik Hendrik als krijgsman die het water beheerst. 47 De meeste van de gebruikte afbeeldingen komen uit het Allegorie op de tijd. 49 publiek domein van sites als wikipedia, maar ook van het Rijksmuseum, het archief van het RKD te ‘s Gravenhage zuidwand 51 en de KB te ‘s Gravenhage Alle mij bekende bronnen zijn vermeld. -

246 BOEKBESPREKING Jacob Van Campen, Schilder En Bouwmeester

BOEKBESPREKING for a forecourt. He also, to an extent that is hard to define, designed architecture for these patrons, and he must have served them much as Daniel Marot served their successors Jacob van Campen, schilder en bouwmeester 1595-1657. two generations later-designing and directing the execu- By P. T. A. Swillens. 302 pp. (19 figs.) Assen. tion of complex schemes of decoration and able to turn his hand to architecture as well. It was through his know- Ten years after Hendrik de Keyser's death in 1621 his ledge of architecture, however, that he first came to work colleague in the City Works of Amsterdam, the chief master for the Stadholder's circle (the Mauritshuis and Huygens' mason Cornelis Danckerts, published the first monograph house were mentioned by Anslo as early as 1648 as bearing on a Dutch architect, his Architectura moderna. Not all De witness to his architectural skill) and Huygens' resounding Keyser's works are included, but the picture that it gives and repeated praise was almost exclusively for his architec- is balanced, and it perceptively lays stress, even in its title, tural achievements: he was the 'vindicator of Vitruvius'. on a change in Dutch architecture which was heralded in it was he who 'admonished Gothic curly foolery with the De Keyser's works. The Haarlem painter and architect stately Roman, and drove old Heresy away before older Salomon de Bray wrote in the introduction: 'Our present Truth'. flourishing age, in which we see the true [i.e. Roman] Within three years of his first contact with the Stad- architecture as resurrected, gives the same to us so libe- holder's circle Van Campen was working for the city rally.. -

Divers Things: Collecting the World Under Water

Hist. Sci., xlix (2011) DIVERS THINGS: COLLECTING THE WORLD UNDER WATER James Delbourgo Rutgers University I do not pretend to have been to the bottom of the sea. Robert Boyle, 1670 matter out of place Consider the following object as shown in an early eighteenth-century engraving (Figure 1). It is a piece of wood — not a highly worked thing, not ingeniously wrought, though it is an artefact of human labour rather than a natural body. Or is it? In the engraving, the piece of wood disappears: it is visible towards the bottom of the image, a sober pointed stump, but it is quickly subsumed by a second, enveloping entity that swirls about it in an embroidering corkscrew. What elements are here intertwin- ing? The legend beneath the engraving identifies the artefact thus: “Navis, prope Hispaniolam ann Dom 1659. Naufragium passae, asser, a clavo ferreo transfixus, corallio aspero candicante I. B. Obsitus, & a fundo maris anno 1687 expiscatus.” It describes a stake or spar from a ship wrecked off Hispaniola in 1659, which is transfixed by both an iron bolt and rough whitish coral, fished out of the depths in 1687. This collector’s item is neither the cliché of exemplarily beautiful coral nor straightforwardly a historical relic, but an intertwining of the two: the “transfixing” of a remnant of maritime technology by an aquatic agent. It exhibits the very proc- ess of encrustation. The spar is juxtaposed with the image of a jellyfish, and more proximately, engravings of Spanish silver coins, also encrusted with coral: “Nummus argenteus Hispanicus … incrustatus”, one of the labels reads.1 Still another illustra- tion, in a separate engraving, bears the legend “Frustum ligni e mari atlantico erutum cui adhaerescunt conchae anatiferae margine muricata” — a piece of “drift wood beset with bernecle [sic] shells”. -

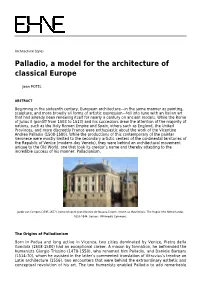

Palladio, a Model for the Architecture of Classical Europe

Architectural Styles Palladio, a model for the architecture of classical Europe Jean POTEL ABSTRACT Beginning in the sixteenth century, European architecture—in the same manner as painting, sculpture, and more broadly all forms of artistic expression—fell into tune with an Italian art that had already been renewing itself for nearly a century on ancient models. While the Rome of Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) and his successors drew the attention of the majority of nations, such as the Holy Roman Empire and Spain, others such as England, the United Provinces, and more discreetly France were enthusiastic about the work of the Vicentine Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). While the productions of this contemporary of the painter Veronese were mostly limited to the secondary artistic centers of the continental territories of the Republic of Venice (modern-day Veneto), they were behind an architectural movement unique to the Old World, one that took its creator’s name and thereby attesting to the incredible success of his manner: Palladianism. Jacob van Campen (1595-1657), home of count Jean-Maurice de Nassau-Siegen, known as Mauritshuis, The Hague (the Netherlands), 1633-1644. Source : Wikimedia Commons. The Origins of Palladianism Born in Padua and long active in Vicenza, two cities dominated by Venice, Pietro della Gondola (1508-1580) had an exceptional career. A mason by formation, he befriended the humanists Giorgio Trissino (1478-1550), who renamed him Palladio, and Daniele Barbaro (1514-70), whom he assisted in the latter’s commented translation of Vitruvius’s treatise on Latin architecture (1556), two encounters that were behind the extraordinary esthetic and conceptual revolution of his art. -

ROYAL NAVY LOSS LIST COMPLETE DATABASE LASTUPDATED - 29OCTOBER 2017 Royal Navy Loss List Complete Database Page 2 of 208

ROYAL NAVY LOSS LIST COMPLETE DATABASE LAST UPDATED - 29 OCTOBER 2017 Photo: Swash Channel wreck courtesy of Bournemouth University MAST is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales, number 07455580 and charity number 1140497 | www.thisismast.org | [email protected] Royal Navy Loss List complete database Page 2 of 208 The Royal Navy (RN) Loss List (LL), from 1512-1947, is compiled from the volumes MAST hopes this will be a powerful research tool, amassing for the first time all RN and websites listed below from the earliest known RN wreck. The accuracy is only as losses in one place. It realises that there will be gaps and would gratefully receive good as these sources which have been thoroughly transcribed and cross-checked. any comments. Equally if researchers have details on any RN ships that are not There will be inevitable transcription errors. The LL includes minimal detail on the listed, or further information to add to the list on any already listed, please contact loss (ie. manner of loss except on the rare occasion that a specific position is known; MAST at [email protected]. MAST also asks that if this resource is used in any also noted is manner of loss, if known ie. if burnt, scuttled, foundered etc.). In most publication and public talk, that it is acknowledged. cases it is unclear from the sources whether the ship was lost in the territorial waters of the country in question, in the EEZ or in international waters. In many cases ships Donations are lost in channels between two countries, eg. -

The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ANGLO-DUTCH WARS OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J.R. Jones | 254 pages | 01 May 1996 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780582056305 | English | London, United Kingdom The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century PDF Book The article you want to access is behind a paywall. In England, the mood was bellicose: the country hoped to frustrate Dutch trade to such an extent that they would be able to become the dominant trading nation. The Netherlands were attacked on land and at sea. The First War — took place during the Interregnum in England, the period after the Civil War when England did not have a king or queen. There are not enough superlatives to describe Michiel De Ruyter. Anglo-Dutch Wars series of wars during the 17th and 18 century. After negotiations broke down, St John drafted the provocative Navigation Act of October , which greatly increased tensions between the two nations. Important to know When you subscribe, you give permission for an automatic re-subscription. Newer Post Older Post Home. Book Description Pearson Education, During the winter and spring of , large numbers of Dutch vessels were intercepted and searched by English ships. His sister-in-law, Queen Anne would also die of Smallpox. It ended with the English Navy gaining control of these seas and a monopoly over trade with the English colonies. The bad thing about the regime change in the Netherlands was that Jan De Witt had achieved an understanding of naval warfare, while William III was totally ignorant, and remained so for the rest of his life. -

M Aritime History

Maritime history Antiquariaat Forum & Asher Rare Books 1 Exten- sive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and sub- ject to prior sale. All items in this list are com- plete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be re- turned within one week after receipt. Prices are in eur (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code. html> New customers are requested to pro- vide references when ordering. ANTIL UARIAAT FORUM Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 MS ‘t Goy 3997 MS ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com v 1.1 · 07 Jul 2021 front cover: no. 51 Dutch trade, whaling, herring fishery, etc., with magnificent views of the harbours of the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies ca. 1772-ca. 1781, including a wide variety of boats and ships 1.