Lens Adaptation to Glutathione Deficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

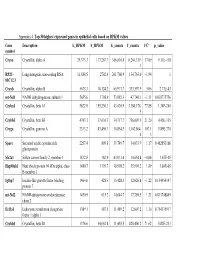

Appendix 4. Top 50 Highest Expressed Genes in Epithelial Cells Based on RPKM Values

Appendix 4. Top 50 highest expressed genes in epithelial cells based on RPKM values Gene Description E_RPKM F_RPKM E_counts F_counts FC* p_value symbol Cryaa Crystallin, alpha A 29,373.3 177,267.7 366,616.4 6,264,319. 17.09 9.11E-118 1 RP23– Long intergenic non-coding RNA 11,888.5 2702.4 261,760.9 134,763.0 −1.94 1 81C12.3 Cryab Crystallin, alpha B 5673.3 10,124.2 65,971.7 333,597.9 5.06 2.71E-43 mt-Nd1 NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 1 5655.6 1798.9 53,082.3 47,748.1 −1.11 0.838775756 Cryba1 Crystallin, beta A1 5622.0 155,230.3 43,420.9 3,380,176. 77.85 1.34E-240 5 Crybb3 Crystallin, beta B3 4743.1 37,636.3 34,717.7 736,007.9 21.20 4.45E-135 Cryga Crystallin, gamma A 2333.2 83,496.3 10,854.5 1,162,864. 107.1 5.89E-270 6 3 Sparc Secreted acidic cysteine rich 2257.4 809.8 39,749.7 34,033.9 −1.17 0.462853166 glycoprotein Slc2a1 Solute carrier family 2, member 1 1832.8 162.9 43,031.4 10,654.8 −4.04 1.67E-05 Hsp90ab1 Heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha, class 1480.7 1139.7 18,998.2 35,901.2 1.89 3.84E-05 B member 1 Igfbp7 Insulin-like growth factor binding 1464.6 428.3 15,428.3 12,626.8 −1.22 0.154954147 protein 7 mt-Nd2 NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 1450.9 615.2 14,644.7 17,789.5 1.21 0.833748849 chain 2 Eef1a1 Eukaryotic translation elongation 1389.1 587.5 11,489.2 12,607.2 1.10 0.754135917 factor 1 alpha 1 Crybb1 Crystallin, beta B1 1376.6 34,662.8 11,455.5 820,406.2 71.62 5.82E-233 Htra3 HtrA serine peptidase 3 1338.6 162.0 23,197.6 6433.9 −3.61 3.93E-05 Gnb2l1 Guanine nucleotide-binding protein 1293.3 670.1 14,495.1 21,652.1 1.49 0.001685952 -

CRYGB Rabbit Pab

Leader in Biomolecular Solutions for Life Science CRYGB Rabbit pAb Catalog No.: A14569 Basic Information Background Catalog No. Crystallins are separated into two classes: taxon-specific, or enzyme, and ubiquitous. A14569 The latter class constitutes the major proteins of vertebrate eye lens and maintains the transparency and refractive index of the lens. Since lens central fiber cells lose their Observed MW nuclei during development, these crystallins are made and then retained throughout 21kDa life, making them extremely stable proteins. Mammalian lens crystallins are divided into alpha, beta, and gamma families; beta and gamma crystallins are also considered as a Calculated MW superfamily. Alpha and beta families are further divided into acidic and basic groups. 20kDa Seven protein regions exist in crystallins: four homologous motifs, a connecting peptide, and N- and C-terminal extensions. Gamma-crystallins are a homogeneous group of Category highly symmetrical, monomeric proteins typically lacking connecting peptides and terminal extensions. They are differentially regulated after early development. Four Primary antibody gamma-crystallin genes (gamma-A through gamma-D) and three pseudogenes (gamma-E, gamma-F, gamma-G) are tandemly organized in a genomic segment as a Applications gene cluster. Whether due to aging or mutations in specific genes, gamma-crystallins WB have been involved in cataract formation. Cross-Reactivity Mouse, Rat Recommended Dilutions Immunogen Information WB 1:500 - 1:2000 Gene ID Swiss Prot 1419 P07316 Immunogen Recombinant fusion protein containing a sequence corresponding to amino acids 80-135 of human CRYGB (NP_005201.2). Synonyms CRYGB;CRYG2;CTRCT39 Contact Product Information www.abclonal.com Source Isotype Purification Rabbit IgG Affinity purification Storage Store at -20℃. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Investigation of Candidate Genes and Mechanisms Underlying Obesity

Prashanth et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:80 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00718-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules G. Prashanth1 , Basavaraj Vastrad2 , Anandkumar Tengli3 , Chanabasayya Vastrad4* and Iranna Kotturshetti5 Abstract Background: Obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder ; however, the etiology of obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus remains largely unknown. There is an urgent need to further broaden the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods: To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that might play essential roles in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus, the publicly available expression profiling by high throughput sequencing data (GSE143319) was downloaded and screened for DEGs. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The protein - protein interaction network, miRNA - target genes regulatory network and TF-target gene regulatory network were constructed and analyzed for identification of hub and target genes. The hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and RT- PCR analysis. Finally, a molecular docking study was performed on over expressed proteins to predict the target small drug molecules. Results: A total of 820 DEGs were identified between -

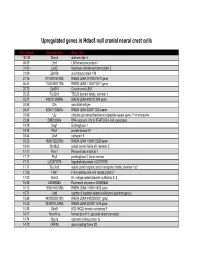

Supp Table 1.Pdf

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Expression of Crystallins in Mouse Retina Jinghua Xi Washington University School of Medicine in St

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2003 A comprehensive analysis of the expression of crystallins in mouse retina Jinghua Xi Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Rafal Farjo University of Michigan - Ann Arbor Shigeo Yoshida University of Michigan - Ann Arbor Timothy S. Kern Case Western Reserve University Anand Swaroop University of Michigan - Ann Arbor See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Xi, Jinghua; Farjo, Rafal; Yoshida, Shigeo; Kern, Timothy S.; Swaroop, Anand; and Andley, Usha P., ,"A comprehensive analysis of the expression of crystallins in mouse retina." Molecular Vision.9,. 410-419. (2003). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/1801 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jinghua Xi, Rafal Farjo, Shigeo Yoshida, Timothy S. Kern, Anand Swaroop, and Usha P. Andley This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/1801 Molecular Vision 2003; 9:410-9 <http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v9/a53> © 2003 Molecular Vision Received 28 May 2003 | Accepted 19 August 2003 | Published 28 August 2003 A comprehensive analysis of the expression of crystallins in mouse retina Jinghua Xi,1 Rafal Farjo,3 Shigeo Yoshida,3 Timothy S. Kern,5 Anand Swaroop,3,4 Usha P. Andley1,2 Departments of 1Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and 2Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. -

Related Macular Degeneration and Cutis Laxa

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Genetic studies of age-related macular degeneration Baas, D.C. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Baas, D. C. (2012). Genetic studies of age-related macular degeneration. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:05 Oct 2021 G������ S������ �� A��-������� M������ D����������� D����������� M������ G������ S������ �� A��-������� | 2012 D�������� C. B��� G������ S������ �� A��-������� M������ D����������� D�������� C. B��� cover.indd 1 31-10-12 08:36 Genetic Studies of Age-related Macular Degeneration Dominique C. Baas Chapter 0.indd 1 23-10-12 19:24 The research described in this thesis was conducted at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience (NIN), an institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Department of Clinical and Molecular Ophthalmogenetics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

Alt Haplotypes Refseq Curated Sequences Snps Dnase Clusters

Scale 50 Mb hg19 chr13: 50,000,000 100,000,000 Haplotypes to GRCh37 Reference Sequence Patches to GRCh37 Reference Sequence gl582975.1 Reference Assembly Alternate Haplotype Sequence Alignments Alt Haplotypes UCSC Genes (RefSeq, GenBank, CCDS, Rfam, tRNAs & Comparative Genomics) LINC00417 RNF17 MEDAG U6 U6 ESD NEK5 7SK PCDH9 MZT1 RBM26 MIR4500 GPC6 7SK DAOA ING1 DQ586768 RNF17 HSPH1 ALG5 DGKH ESD NEK3 DIAPH3 PCDH9 BORA RBM26 SLITRK5 GPC6 ZIC5 DAOA ING1 DQ579288 CENPJ HSPH1 ALG5 DGKH MED4 PRR20D PCDH9 BORA RBM26 SLITRK5 GPC6 ZIC2 DAOA ING1 DQ587539 CENPJ HSPH1 ALG5 DGKH MED4 PRR20D PCDH9 BORA RBM26 SLITRK5 DCT PCCA LIG4 F7 ANKRD20A9P CENPJ HSPH1 POSTN LACC1 RB1 PRR20D BC042366 BORA RBM26 LINC00433 DCT PCCA LIG4 F7 BC035261 CENPJ HSPH1 POSTN LACC1 RB1 PRR20B U7 DIS3 RBM26 LINC00353 DZIP1 FGF14 LIG4 F7 DQ572285 CENPJ HSPH1 POSTN SERP2 EBPL PRR20E PCDH9-AS2 DIS3 RBM26 LINC00559 OXGR1 TPP2 LIG4 F7 LINC00442 AMER2 RXFP2 UFM1 SERP2 EBPL PCDH17 PCDH9 DIS3 NDFIP2 MIR622 OXGR1 BIVM LIG4 F10 RNU6-52P AMER2 RXFP2 UFM1 TRNA BCMS PCDH17 LINC00550 UCHL3 SLITRK1 U6 OXGR1 BIVM LIG4 F10 TUBA3C AMER2 FRY UFM1 GTF2F2 BCMS PCDH17 KLHL1 LMO7 LINC00351 GPC5 IPO5 DAOA ING1 ANKRD26P3 RNF6 FRY FREM2 KCTD4 BCMS DIAPH3 KLHL1 LMO7 SLITRK6 Y_RNA IPO5 DAOA ING1 LINC00421 RNF6 FRY FREM2 KCTD4 BCMS DIAPH3 ATXN8OS LMO7 SLITRK6 5S_rRNA PCCA ABHD13 F10 TPTE2 RNF6 FRY NHLRC3 TPT1 BCMS DIAPH3 Y_RNA IRG1 MIR4500HG TRNA GGACT ABHD13 GRK1 TPTE2 RNF6 ZAR1L NHLRC3 TPT1 BCMS DIAPH3 LINC00348 IRG1 BC038529 MBNL2 BIVM MYO16 TPTE2 RNF6 BRCA2 NHLRC3 TPT1 BCMS DIAPH3 DACH1 CLN5 LINC00410 -

Human Astrocytes: Structure and Functions in the Healthy Brain

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1383-5 REVIEW Human astrocytes: structure and functions in the healthy brain Flora Vasile1 · Elena Dossi1 · Nathalie Rouach1 Received: 4 November 2016 / Accepted: 6 February 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Data collected on astrocytes’ physiology in the Introduction rodent have placed them as key regulators of synaptic, neu- ronal, network, and cognitive functions. While these find- Since the early discovery that the range of astroglial func- ings proved highly valuable for our awareness and appreci- tions extends considerably beyond passive structural sup- ation of non-neuronal cell significance in brain physiology, port, astrocytes have cemented their position as crucial early structural and phylogenic investigations of human determinants of proper neuronal function. Astrocytes are astrocytes hinted at potentially different astrocytic proper- now considered as full-fledged participants in brain cir- ties. This idea sparked interest to replicate rodent-based cuitry and processing, and display a large spectrum of studies on human samples, which have revealed an analo- functions at the cell level, such as the formation, matura- gous but enhanced involvement of astrocytes in neuronal tion and elimination of synapses, ionic homeostasis, clear- function of the human brain. Such evidence pointed to a ance of neurotransmitters, regulation of extracellular space central role of human astrocytes in sustaining more com- volume, and modulation of synaptic activity and plastic- plex information processing. Here, we review the current ity (Araque et al. 2014; Dallérac and Rouach 2016). It has state of our knowledge of human astrocytes regarding their additionally been demonstrated that they are involved in structure, gene profile, and functions, highlighting the dif- rhythm generation and neuronal network patterns (Fellin ferences with rodent astrocytes. -

TITLE PAGE Oxidative Stress and Response to Thymidylate Synthase

Downloaded from molpharm.aspetjournals.org at ASPET Journals on October 2, 2021 -Targeted -Targeted 1 , University of of , University SC K.W.B., South Columbia, (U.O., Carolina, This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. -

Congenital Cataracts Due to a Novel 2‑Bp Deletion in CRYBA1/A3

1614 MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 10: 1614-1618, 2014 Congenital cataracts due to a novel 2‑bp deletion in CRYBA1/A3 JING ZHANG1, YANHUA ZHANG1, FANG FANG1, WEIHONG MU1, NING ZHANG2, TONGSHUN XU3 and QINYING CAO1 1Prenatal Diagnosis Center, Shijiazhuang Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital; 2Department of Cardiology, The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University; 3Department of Surgery, Shijiazhuang Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, P.R. China Received September 22, 2013; Accepted April 11, 2014 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2324 Abstract. Congenital cataracts, which are a clinically and located in the eye lens. The major human crystallins comprise genetically heterogeneous group of eye disorders, lead to 90% of protein in the mature lens and contain two different visual impairment and are a significant cause of blindness superfamilies: the small heat‑shock proteins (α-crystallins) in childhood. A major proportion of the causative mutations and the βγ-crystallins. for congenital cataracts are found in crystallin genes. In the In this study a functional candidate approach was used present study, a novel deletion mutation (c.590-591delAG) in to investigate the known crystallin genes, including CRYAA, exon 6 of CRYBA1/A3 was identified in a large family with CRYAB, CRYBA1/A3, CRYBB1, CRYBB2, CRYGC, CRYGD autosomal dominant congenital cataracts. An increase in and CRYGS, in which a major proportion of the mutations local hydrophobicity was predicted around the mutation site; identified in a large family with congenital cataracts were however, further studies are required to determine the exact found. effect of the mutation on βA1/A3-crystallin structure and function. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report Subjects and methods of an association between a frameshift mutation in exon 6 of CRYBA1/A3 and congenital cataracts.