Neonicotinoid Exposure Affects Foraging, Nesting, and Reproductive Success of Ground-Nesting 2 Solitary Bees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin Bee Identification Guide

WisconsinWisconsin BeeBee IdentificationIdentification GuideGuide Developed by Patrick Liesch, Christy Stewart, and Christine Wen Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) The honey bee is perhaps our best-known pollinator. Honey bees are not native to North America and were brought over with early settlers. Honey bees are mid-sized bees (~ ½ inch long) and have brownish bodies with bands of pale hairs on the abdomen. Honey bees are unique with their social behavior, living together year-round as a colony consisting of thousands of individuals. Honey bees forage on a wide variety of plants and their colonies can be useful in agricultural settings for their pollination services. Honey bees are our only bee that produces honey, which they use as a food source for the colony during the winter months. In many cases, the honey bees you encounter may be from a local beekeeper’s hive. Occasionally, wild honey bee colonies can become established in cavities in hollow trees and similar settings. Photo by Christy Stewart Bumble bees (Bombus sp.) Bumble bees are some of our most recognizable bees. They are amongst our largest bees and can be close to 1 inch long, although many species are between ½ inch and ¾ inch long. There are ~20 species of bumble bees in Wisconsin and most have a robust, fuzzy appearance. Bumble bees tend to be very hairy and have black bodies with patches of yellow or orange depending on the species. Bumble bees are a type of social bee Bombus rufocinctus and live in small colonies consisting of dozens to a few hundred workers. Photo by Christy Stewart Their nests tend to be constructed in preexisting underground cavities, such as former chipmunk or rabbit burrows. -

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness of Peponapis pruinosa and Apis mellifera on Cucurbita foetidissima A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Biology by Jeremy Raymond Warner Committee in charge: Professor David Holway, Chair Professor Joshua Kohn Professor James Nieh 2017 © Jeremy Raymond Warner, 2017 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Jeremy Raymond Warner is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………... v List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. vi List of Appendices………………………………………………………………………. vii Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………... viii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………… ix Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Study System……………………………………………..………………………. 5 Pollinator Effectiveness……………………………………….………………….. 5 Data Analysis……..…………………………………………………………..….. 8 Results…………………………………………………………………………………... 10 Plant trait regressions……………………………………………………..……... 10 Fruit set……………………………………………………...…………………... 10 Fruit volume, seed number, -

The Very Handy Bee Manual

The Very Handy Manual: How to Catch and Identify Bees and Manage a Collection A Collective and Ongoing Effort by Those Who Love to Study Bees in North America Last Revised: October, 2010 This manual is a compilation of the wisdom and experience of many individuals, some of whom are directly acknowledged here and others not. We thank all of you. The bulk of the text was compiled by Sam Droege at the USGS Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab over several years from 2004-2008. We regularly update the manual with new information, so, if you have a new technique, some additional ideas for sections, corrections or additions, we would like to hear from you. Please email those to Sam Droege ([email protected]). You can also email Sam if you are interested in joining the group’s discussion group on bee monitoring and identification. Many thanks to Dave and Janice Green, Tracy Zarrillo, and Liz Sellers for their many hours of editing this manual. "They've got this steamroller going, and they won't stop until there's nobody fishing. What are they going to do then, save some bees?" - Mike Russo (Massachusetts fisherman who has fished cod for 18 years, on environmentalists)-Provided by Matthew Shepherd Contents Where to Find Bees ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Nets ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Netting Technique ...................................................................................................................................... -

Foraging Behavior of the Honey Bee

Bulletin of Pure and Applied Sciences Print version ISSN 0970 0765 Vol.38A (Zoology), No.2, Online version ISSN 2320 3188 July-December 2019: P.52-60 DOI 10.5958/2320-3188.2019.00006.8 Original Research Article Available online at www.bpasjournals.com Foraging Behavior of the Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) upon the Male and Female Flowers of Squash (Cucurbita pepo L.) (Cucurbitaceae) in the Region of Tizi-Ouzou (Algeria) 1Korichi Y. Abstract: 2Aouar-Sadli M. Cucurbitaceae species depend on pollination by 3Khelfane-Goucem K. bees for fruit production. The objective of this 4Ikhlef H. present work was to identify the insect visitors of squash and to study the foraging behavior of the Author’s Affiliation: most abundant species in the field. Identification 1,2,4Laboratoire de production, amélioration et of foraging insects of Cucurbita pepo L. protection des végétaux et denrées alimentaires. (Cucurbitaceae) were performed during 2016 and Faculté des sciences biologiques et des sciences 2017 flowering periods in the region of Tizi- agronomiques. Université Mouloud Ouzou (Algeria). Observations showed that the Mammeri de Tizi-Ouzou. majority of the insects visiting squash flowers E-mail: [email protected] (Korichi) were Apoides Hymenoptera belonging to two [email protected] (Aouar-Sadli) families: Apidae and Halictidae. Six species of [email protected] (Ikhlef) bees were recorded upon the plant, of which the 3Laboratoire de Production, sauvegarde des honey bee Apis mellifera L. was the most frequent espèces menacées et des récoltes. Faculté des species. The study of the foraging activity of sciences biologiques et des sciences these insects showed that their visits to squash agronomiques. -

Floral Guilds of Bees in Sagebrush Steppe: Comparing Bee Usage Of

ABSTRACT: Healthy plant communities of the American sagebrush steppe consist of mostly wind-polli- • nated shrubs and grasses interspersed with a diverse mix of mostly spring-blooming, herbaceous perennial wildflowers. Native, nonsocial bees are their common floral visitors, but their floral associations and abundances are poorly known. Extrapolating from the few available pollination studies, bees are the primary pollinators needed for seed production. Bees, therefore, will underpin the success of ambitious seeding efforts to restore native forbs to impoverished sagebrush steppe communities following vast Floral Guilds of wildfires. This study quantitatively characterized the floral guilds of 17 prevalent wildflower species of the Great Basin that are, or could be, available for restoration seed mixes. More than 3800 bees repre- senting >170 species were sampled from >35,000 plants. Species of Osmia, Andrena, Bombus, Eucera, Bees in Sagebrush Halictus, and Lasioglossum bees prevailed. The most thoroughly collected floral guilds, at Balsamorhiza sagittata and Astragalus filipes, comprised 76 and 85 native bee species, respectively. Pollen-specialists Steppe: Comparing dominated guilds at Lomatium dissectum, Penstemon speciosus, and several congenerics. In contrast, the two native wildflowers used most often in sagebrush steppe seeding mixes—Achillea millefolium and Linum lewisii—attracted the fewest bees, most of them unimportant in the other floral guilds. Suc- Bee Usage of cessfully seeding more of the other wildflowers studied here would greatly improve degraded sagebrush Wildflowers steppe for its diverse native bee communities. Index terms: Apoidea, Asteraceae, Great Basin, oligolecty, restoration Available for Postfire INTRODUCTION twice a decade (Whisenant 1990). Massive Restoration wildfires are burning record acreages of the The American sagebrush steppe grows American West; two fires in 2007 together across the basins and foothills over much burned >500,000 ha of shrub-steppe and 1,3 James H. -

Sown Wildflowers Enhance Habitats of Pollinators and Beneficial

plants Article Sown Wildflowers Enhance Habitats of Pollinators and Beneficial Arthropods in a Tomato Field Margin Vaya Kati 1,* , Filitsa Karamaouna 1,* , Leonidas Economou 1, Photini V. Mylona 2 , Maria Samara 1 , Mircea-Dan Mitroiu 3 , Myrto Barda 1 , Mike Edwards 4 and Sofia Liberopoulou 1 1 Scientific Directorate of Pesticides Control and Phytopharmacy, Benaki Phytopathological Institute, 8 Stefanou Delta Str., 14561 Kifissia, Greece; [email protected] (L.E.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (S.L.) 2 HAO-DEMETER, Institute of Plant Breeding & Genetic Resources, 570 01 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Biology, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Bd. Carol I 20A, 700505 Ias, i, Romania; [email protected] 4 Mike Edwards Ecological and Data Services Ltd., Midhurst GU29 9NQ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (V.K.); [email protected] (F.K.); Tel.: +30-210-8180-246 (V.K.); +30-210-8180-332 (F.K.) Abstract: We evaluated the capacity of selected plants, sown along a processing tomato field margin in central Greece and natural vegetation, to attract beneficial and Hymenoptera pollinating insects and questioned whether they can distract pollinators from crop flowers. Measurements of flower cover and attracted pollinators and beneficial arthropods were recorded from early-May to mid-July, Citation: Kati, V.; Karamaouna, F.; during the cultivation period of the crop. Flower cover was higher in the sown mixtures compared Economou, L.; Mylona, P.V.; Samara, to natural vegetation and was positively correlated with the number of attracted pollinators. -

Atlas of Pollen and Plants Used by Bees

AtlasAtlas ofof pollenpollen andand plantsplants usedused byby beesbees Cláudia Inês da Silva Jefferson Nunes Radaeski Mariana Victorino Nicolosi Arena Soraia Girardi Bauermann (organizadores) Atlas of pollen and plants used by bees Cláudia Inês da Silva Jefferson Nunes Radaeski Mariana Victorino Nicolosi Arena Soraia Girardi Bauermann (orgs.) Atlas of pollen and plants used by bees 1st Edition Rio Claro-SP 2020 'DGRV,QWHUQDFLRQDLVGH&DWDORJD©¥RQD3XEOLFD©¥R &,3 /XPRV$VVHVVRULD(GLWRULDO %LEOLRWHF£ULD3ULVFLOD3HQD0DFKDGR&5% $$WODVRISROOHQDQGSODQWVXVHGE\EHHV>UHFXUVR HOHWU¶QLFR@RUJV&O£XGLD,Q¬VGD6LOYD>HW DO@——HG——5LR&ODUR&,6(22 'DGRVHOHWU¶QLFRV SGI ,QFOXLELEOLRJUDILD ,6%12 3DOLQRORJLD&DW£ORJRV$EHOKDV3µOHQ– 0RUIRORJLD(FRORJLD,6LOYD&O£XGLD,Q¬VGD,, 5DGDHVNL-HIIHUVRQ1XQHV,,,$UHQD0DULDQD9LFWRULQR 1LFRORVL,9%DXHUPDQQ6RUDLD*LUDUGL9&RQVXOWRULD ,QWHOLJHQWHHP6HUYL©RV(FRVVLVWHPLFRV &,6( 9,7¯WXOR &'' Las comunidades vegetales son componentes principales de los ecosistemas terrestres de las cuales dependen numerosos grupos de organismos para su supervi- vencia. Entre ellos, las abejas constituyen un eslabón esencial en la polinización de angiospermas que durante millones de años desarrollaron estrategias cada vez más específicas para atraerlas. De esta forma se establece una relación muy fuerte entre am- bos, planta-polinizador, y cuanto mayor es la especialización, tal como sucede en un gran número de especies de orquídeas y cactáceas entre otros grupos, ésta se torna más vulnerable ante cambios ambientales naturales o producidos por el hombre. De esta forma, el estudio de este tipo de interacciones resulta cada vez más importante en vista del incremento de áreas perturbadas o modificadas de manera antrópica en las cuales la fauna y flora queda expuesta a adaptarse a las nuevas condiciones o desaparecer. -

(Native) Bee Basics

A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Cover Art: Upper panel: The southeastern blueberry bee Habropoda( laboriosa) visiting blossoms of Rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum). Lower panel: Female andrenid bees (Andrena cornelli) foraging for nectar on Azalea (Rhododendron canescens). A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics: An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Illustrations by Steve Buchanan A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication United States Department of Agriculture Acknowledgments Edited by Larry Stritch, Ph.D. Julie Nelson Teresa Prendusi Laurie Davies Adams Worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) visiting almond blossoms (Prunus dulcis). Introduction Native bees are a hidden treasure. From alpine meadows in the national forests of the Rocky Mountains to the Sonoran Desert in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona and from the boreal forests of the Tongass National Forest in Alaska to the Ocala National Forest in Florida, bees can be found anywhere in North America, where flowers bloom. From forests to farms, from cities to wildlands, there are 4,000 native bee species in the United States, from the tiny Perdita minima to large carpenter bees. Most people do not realize that there were no honey bees in America before European settlers brought hives from Europe. These resourceful animals promptly managed to escape from domestication. As they had done for millennia in Europe and Asia, honey bees formed swarms and set up nests in hollow trees. -

Bacterial Communities of Herbivores and Pollinators That Have Co-Evolved Cucurbita Spp

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/691378; this version posted July 3, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Bacterial communities of herbivores and pollinators that have co-evolved Cucurbita spp. 3 4 5 Lori R. Shapiro1, 2, Madison Youngblom3, Erin D. Scully4, Jorge Rocha5, Joseph Nathaniel 6 Paulson6, Vanja Klepac-Ceraj7, Angélica Cibrián-Jaramillo8, Margarita M. López-Uribe9 7 8 1 Department of Applied Ecology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27695 USA 9 2 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 10 USA 02138 11 3 Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 12 Madison WI, 53706 USA 13 4 Center for Grain and Animal Health Research, Stored Product Insect and Engineering Research 14 Unit, USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Manhattan, KS, 66502 USA 15 5 Conacyt-Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo en Agrobiotecnología Alimentaria, San Agustin 16 Tlaxiaca, Mexico 42162 17 6 Department of Biostatistics, Product Development, Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, 18 California 94102 19 7 Department of Biological Sciences, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA 02481 USA 16803 20 8 Laboratorio Nacional de Genómica para la Biodiversidad, Centro de Investigación y de 21 Estudios Avanzados del IPN, Irapuato, Mexico 36284 22 9 Department of Entomology, Center for Pollinator Research, Pennsylvania State University, 23 University Park, PA 24 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/691378; this version posted July 3, 2019. -

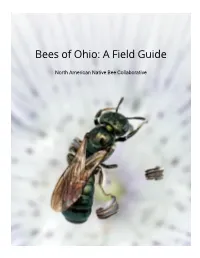

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

Colony Collapse Disorder Progress Report

Colony Collapse Disorder Progress Report CCD Steering Committee June 2009 CCD Steering Committee Members Federal: Kevin Hackett USDA Agricultural Research Service (co-chair) Rick Meyer USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Mary Purcell-Miramontes and Extension Service (co-chair) Robyn Rose USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Doug Holy USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Evan Skowronski Department of Defense Tom Steeger Environmental Protection Agency Land Grant University: Bruce McPheron Pennsylvania State University Sonny Ramaswamy Purdue University This report has been cleared by all USDA agencies involved, and EPA. DoD considers this a USDA publication, to which DoD has contributed technical input. 2 Content Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Topic I: Survey and (Sample) Data Collection 7 Topic II: Analysis of Existing Samples 7 Topic III: Research to Identify Factors Affecting Honey Bee Health, Including Attempts to Recreate CCD Symptomology 8 Topic IV: Mitigative and Preventive Measures 9 Appendix: Specific Accomplishments by Action Plan Component 11 Topic I: Survey and Data Collection 11 Topic II: Analysis of Existing Samples 14 Topic III: Research to Identify Factors Affecting Honey Bee Health, Including Attempts to Recreate CCD Symptomology 21 Topic IV: Mitigative and Preventive Measures 29 3 Executive Summary Mandated by the 2008 Farm Bill [Section 7204 (h) (4)], this first annual report on Honey Bee Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) represents the work of a large number of scientists from 8 Federal agencies, 2 state departments of agriculture, 22 universities, and several private research efforts. In response to the unexplained losses of U.S. honey bee colonies now known as colony collapse disorder (CCD), USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES) led a collaborative effort to define an approach to CCD, resulting in the CCD Action Plan in July 2007.