Ecology of the Squash and Gourd Bee, Cucurbits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods

insects Review A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods in Agroecosystems Kenneth W. McCravy Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, 1 University Circle, Macomb, IL 61455, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-309-298-2160 Received: 12 September 2018; Accepted: 19 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Beneficial arthropods provide many important ecosystem services. In agroecosystems, pollination and control of crop pests provide benefits worth billions of dollars annually. Effective sampling and monitoring of these beneficial arthropods is essential for ensuring their short- and long-term viability and effectiveness. There are numerous methods available for sampling beneficial arthropods in a variety of habitats, and these methods can vary in efficiency and effectiveness. In this paper I review active and passive sampling methods for non-Apis bees and arthropod natural enemies of agricultural pests, including methods for sampling flying insects, arthropods on vegetation and in soil and litter environments, and estimation of predation and parasitism rates. Sample sizes, lethal sampling, and the potential usefulness of bycatch are also discussed. Keywords: sampling methodology; bee monitoring; beneficial arthropods; natural enemy monitoring; vane traps; Malaise traps; bowl traps; pitfall traps; insect netting; epigeic arthropod sampling 1. Introduction To sustainably use the Earth’s resources for our benefit, it is essential that we understand the ecology of human-altered systems and the organisms that inhabit them. Agroecosystems include agricultural activities plus living and nonliving components that interact with these activities in a variety of ways. Beneficial arthropods, such as pollinators of crops and natural enemies of arthropod pests and weeds, play important roles in the economic and ecological success of agroecosystems. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness of Peponapis Pruinosa and Apis Mellifera on Cucurbita Pepo a Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness of Peponapis pruinosa and Apis mellifera on Cucurbita pepo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Biology by Jessica Audrey Davids Committee in charge: Professor David Holway, Chair Professor Joshua Kohn Professor James Nieh 2018 © Jessica Audrey Davids, 2018 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Jessica Audrey Davids is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………... v List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. vi List of Appendices………………………………………………………………………. vii Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………... viii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………… ix Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………... 3 Results…………………………………………………………………………………......7 Estimated pollen deposition….…………………………………………..……......7 Fruit set……………………………………………………...…………………......7 Discussion………………………………………………………………………………....9 References………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Tables…………………………………………………………………………………… 15 Figures………………………………………………………………………………….. -

Wisconsin Bee Identification Guide

WisconsinWisconsin BeeBee IdentificationIdentification GuideGuide Developed by Patrick Liesch, Christy Stewart, and Christine Wen Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) The honey bee is perhaps our best-known pollinator. Honey bees are not native to North America and were brought over with early settlers. Honey bees are mid-sized bees (~ ½ inch long) and have brownish bodies with bands of pale hairs on the abdomen. Honey bees are unique with their social behavior, living together year-round as a colony consisting of thousands of individuals. Honey bees forage on a wide variety of plants and their colonies can be useful in agricultural settings for their pollination services. Honey bees are our only bee that produces honey, which they use as a food source for the colony during the winter months. In many cases, the honey bees you encounter may be from a local beekeeper’s hive. Occasionally, wild honey bee colonies can become established in cavities in hollow trees and similar settings. Photo by Christy Stewart Bumble bees (Bombus sp.) Bumble bees are some of our most recognizable bees. They are amongst our largest bees and can be close to 1 inch long, although many species are between ½ inch and ¾ inch long. There are ~20 species of bumble bees in Wisconsin and most have a robust, fuzzy appearance. Bumble bees tend to be very hairy and have black bodies with patches of yellow or orange depending on the species. Bumble bees are a type of social bee Bombus rufocinctus and live in small colonies consisting of dozens to a few hundred workers. Photo by Christy Stewart Their nests tend to be constructed in preexisting underground cavities, such as former chipmunk or rabbit burrows. -

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pollinator Effectiveness of Peponapis pruinosa and Apis mellifera on Cucurbita foetidissima A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Biology by Jeremy Raymond Warner Committee in charge: Professor David Holway, Chair Professor Joshua Kohn Professor James Nieh 2017 © Jeremy Raymond Warner, 2017 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Jeremy Raymond Warner is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………... v List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. vi List of Appendices………………………………………………………………………. vii Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………... viii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………… ix Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Study System……………………………………………..………………………. 5 Pollinator Effectiveness……………………………………….………………….. 5 Data Analysis……..…………………………………………………………..….. 8 Results…………………………………………………………………………………... 10 Plant trait regressions……………………………………………………..……... 10 Fruit set……………………………………………………...…………………... 10 Fruit volume, seed number, -

The Very Handy Bee Manual

The Very Handy Manual: How to Catch and Identify Bees and Manage a Collection A Collective and Ongoing Effort by Those Who Love to Study Bees in North America Last Revised: October, 2010 This manual is a compilation of the wisdom and experience of many individuals, some of whom are directly acknowledged here and others not. We thank all of you. The bulk of the text was compiled by Sam Droege at the USGS Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab over several years from 2004-2008. We regularly update the manual with new information, so, if you have a new technique, some additional ideas for sections, corrections or additions, we would like to hear from you. Please email those to Sam Droege ([email protected]). You can also email Sam if you are interested in joining the group’s discussion group on bee monitoring and identification. Many thanks to Dave and Janice Green, Tracy Zarrillo, and Liz Sellers for their many hours of editing this manual. "They've got this steamroller going, and they won't stop until there's nobody fishing. What are they going to do then, save some bees?" - Mike Russo (Massachusetts fisherman who has fished cod for 18 years, on environmentalists)-Provided by Matthew Shepherd Contents Where to Find Bees ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Nets ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Netting Technique ...................................................................................................................................... -

(Native) Bee Basics

A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Cover Art: Upper panel: The southeastern blueberry bee Habropoda( laboriosa) visiting blossoms of Rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum). Lower panel: Female andrenid bees (Andrena cornelli) foraging for nectar on Azalea (Rhododendron canescens). A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics: An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Illustrations by Steve Buchanan A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication United States Department of Agriculture Acknowledgments Edited by Larry Stritch, Ph.D. Julie Nelson Teresa Prendusi Laurie Davies Adams Worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) visiting almond blossoms (Prunus dulcis). Introduction Native bees are a hidden treasure. From alpine meadows in the national forests of the Rocky Mountains to the Sonoran Desert in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona and from the boreal forests of the Tongass National Forest in Alaska to the Ocala National Forest in Florida, bees can be found anywhere in North America, where flowers bloom. From forests to farms, from cities to wildlands, there are 4,000 native bee species in the United States, from the tiny Perdita minima to large carpenter bees. Most people do not realize that there were no honey bees in America before European settlers brought hives from Europe. These resourceful animals promptly managed to escape from domestication. As they had done for millennia in Europe and Asia, honey bees formed swarms and set up nests in hollow trees. -

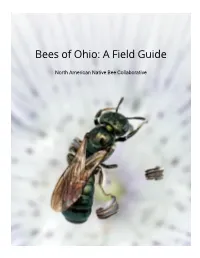

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

Colony Collapse Disorder Progress Report

Colony Collapse Disorder Progress Report CCD Steering Committee June 2009 CCD Steering Committee Members Federal: Kevin Hackett USDA Agricultural Research Service (co-chair) Rick Meyer USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Mary Purcell-Miramontes and Extension Service (co-chair) Robyn Rose USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Doug Holy USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Evan Skowronski Department of Defense Tom Steeger Environmental Protection Agency Land Grant University: Bruce McPheron Pennsylvania State University Sonny Ramaswamy Purdue University This report has been cleared by all USDA agencies involved, and EPA. DoD considers this a USDA publication, to which DoD has contributed technical input. 2 Content Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Topic I: Survey and (Sample) Data Collection 7 Topic II: Analysis of Existing Samples 7 Topic III: Research to Identify Factors Affecting Honey Bee Health, Including Attempts to Recreate CCD Symptomology 8 Topic IV: Mitigative and Preventive Measures 9 Appendix: Specific Accomplishments by Action Plan Component 11 Topic I: Survey and Data Collection 11 Topic II: Analysis of Existing Samples 14 Topic III: Research to Identify Factors Affecting Honey Bee Health, Including Attempts to Recreate CCD Symptomology 21 Topic IV: Mitigative and Preventive Measures 29 3 Executive Summary Mandated by the 2008 Farm Bill [Section 7204 (h) (4)], this first annual report on Honey Bee Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) represents the work of a large number of scientists from 8 Federal agencies, 2 state departments of agriculture, 22 universities, and several private research efforts. In response to the unexplained losses of U.S. honey bee colonies now known as colony collapse disorder (CCD), USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES) led a collaborative effort to define an approach to CCD, resulting in the CCD Action Plan in July 2007. -

Missouri Bee Identification Guide Edward M

Missouri Bee Identification Guide Edward M. Spevak 1, Michael Arduser 2, 1 Saint Louis Zoo 2 Missouri Department of Conservation Bees are Beneficial Honey bees (Apis mellifera) Leafcutter and Mason bees (Megachile spp. & Osmia spp.) Bees play an essential role in natural and agricultural systems Family: Apidae. Heart-shaped head; black Family: Megachilidae. Head as broad as as pollinators of flowering plants that provide food, fiber, to amber-brown body with pale and dark thorax; large mandibles; black body most spices, medicines and animal forage. Plants rely on pollinators stripes on abdomen; pollen baskets on hind with pale bands on abdomen (metallic green to reproduce and set seed and fruit. In fact, approximately legs; 10-15 mm. or blue for Osmia); pollen carrying hairs three-quarters of all flowering plants rely on pollinators to ● Large social colonies, 30,000 or more; live under abdomen; 5-20 mm. reproduce. Honey bees pollinate crops, but native bees also in man-made hives and natural cavities like ● Solitary, but nest in aggregations in have a role in agriculture and are essential for pollination in tree hollows. Swarm to locate new nests. natural or man-made holes such as beetle natural landscapes. There are over 425 native species of ground- ● Honey bees are not native to the U.S., but holes, nesting blocks, stems, or soil. nesting, wood-nesting and parasitic bees found within Missouri. were brought over by Europeans in the ● Females cut circular pieces from leaves This guide identifies 10 groups of bees commonly observed in 17th century. to line their nests. -

Confirmed Presence of the Squash Bee, Peponapis Pruinosa

Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection Vol 3(3) 2–6 Confirmed presence of the squash bee,Peponapis pruinosa (Say, 1837) in the state of Oregon and specimen-based observational records of Peponapis (Say, 1837) (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection Lincoln R. Best1, Christopher J. Marshall1 and Sarah Red-Laird2 1Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis OR 97331 2The Bee Girl Organization, PO Box 3257, Ashland, OR 97520 Cite this work as: Best, L. R., C. J. Marshall and S. Red-Laird. 2019. Confirmed presence of the squash bee, Peponapis pruinosa (Say, 1837) in the state of Oregon and specimen-based observational records of Peponapis (Say, 1837) (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection. 3(3) p 2–6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5399/osu/cat_osac.3.3.4614 Abstract A new Oregon record for Peponapis pruinosa (Say, 1837) is presented with notes on its occurrence and photographs. This record provides the first empirical evidence of the genus and species in the state of Oregon. A dataset of Peponapis (Say, 1837) specimens in the holdings of the Oregon State Arthropod Collection is included with a brief summary of its contents. Introduction Bees of the genus Peponapis (Say, 1837) (Apidae: Eucerini) are known pollen-collecting specialists of Cucurbita Linnaeus, a genus of plants containing native species occurring in Central America, Mexico and the southwestern United States of America (Hurd and Linsley 1964; Hurd et al. 1971). Domesticated Cucurbita species, including pumpkins, summer and fall squashes, marrows, and many other varieties, are widespread throughout North America, and have allowed members of the genus to expand their geographic range (López-Uribe et al. -

Species Lists

Appendix B: Sepcies Lists Appendix B: Species Lists In this appendix: Plants Mammals Birds Pollinators Fish and Mussels Reptiles and Amphibians Plants Scientific Name Common Name Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf Acalypha ostryifolia pineland threeseed mercury Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury Acalypha virginica Virginia threeseed mercury Alliaria petiolata garlic mustard Amaranthus tamariscinus tall amaranth Ambrosia artemisifolia annual ragweed Ambrosia trifida great ragweed Ammannia coccinea valley redstem Amorpha brachycarpa leadplant Ampelopsis cordata heartleaf peppervine Amphicarpaea bracteata var. comosa American hogpeanut Amsonia illustris Ozark bluestar Anemone canadensis Canadian anemone Apocynum cannabinum Indian hemp Aristolochia tomentosa Woolly dutchman's pipe Artemisia annua sweet sagewort Asarum canadense Canadian wildginger Asclepias incarnata swamp milkweed Asclepias purpurascens purple milkweed Asclepias syriaca common milkweed Asclepias verticillata whorled milkweed Aster lateriflorus calico aster Aster pilosus hairy white oldfield aster Aster subulatus eastern annual saltmarsh aster Bergia texana Texas bergia Bidens cernua nodding beggerstick Bidens connata purplestem beggarticks Boehmeria cylindrica smallspike false nettle Callitriche terrestris terrestrial water-starwort Calystegia sepium hedge false bindweed Campsis radicans trumpet creeper Cardamine hirsuta hairy bittercress Carex crus-corvi ravenfoot sedge Carex hyalinolepis shoreline sedge, thinscale sedge Carex molesta troublesome sedge Cassia fasciculata