NEB Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Hearing Transcripts, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Plan – Merritt/Nicola Valley - Page 1

TOURISM PLAN MERRITT/NICOLA VALLE Y,BC 2 0 1 3 / 1 4 Contacts: Destination BC Representatives: Alison McKay (604) 660-3754 [email protected] Simone Carlysle-Smith Thompson Okanagan Tourism Association (250) 860-5999 [email protected] Destination BC Facilitator: Steve Nicol (604) 733-5622 [email protected] Table of Contents 1 Plan Summary and Priorities .......................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction and Strategic Context ................................................................................. 4 2.1 Introduction and Background ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Provincial Context ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.2.1 Community Tourism Foundations Program ................................................................................. 4 2.2.2 Community Tourism Opportunities Program ............................................................................... 4 2.2.3 Tourism Partners Program............................................................................................................ 5 2.3 Thompson Okanagan Regional Strategy ....................................................................................... 5 2.3.1 A new perspective on target markets .......................................................................................... 5 2.3.2 Thompson Okanagan’s -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

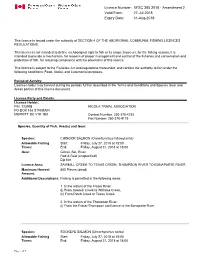

Licence Number: XFSC 285 2018 - Amendment 2 Valid From: 27-Jul-2018 Expiry Date: 31-Aug-2018

Licence Number: XFSC 285 2018 - Amendment 2 Valid From: 27-Jul-2018 Expiry Date: 31-Aug-2018 This licence is issued under the authority of SECTION 4 OF THE ABORIGINAL COMMUNAL FISHING LICENCES REGULATIONS. This licence is not intended to define an Aboriginal right to fish or its scope; however, for the fishing season, it is intended to provide a mechanism, for reasons of proper management and control of the fisheries and conservation and protection of fish, for requiring compliance with the provisions of this licence. This licence is subject to the Fisheries Act and regulations thereunder, and confers the authority to fish under the following conditions: Food, Social, and Ceremonial purposes. Period of Activity: Licence Holder may harvest during the periods further described in the Terms and Conditions and Species Gear and Areas portion of this licence document. Licence Party and Details: Licence Holder: FIN: 123998 NICOLA TRIBAL ASSOCIATION PO BOX 188 STN MAIN MERRITT BC V1K 1B8 Contact Number: 250-378-4235 Fax Number: 250-378-9119 Species, Quantity of Fish, Area(s) and Gear: Species: CHINOOK SALMON (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Allowable Fishing Start: Friday, July 27, 2018 at 18:00 Times: End: Friday, August 31, 2018 at 18:00 Gear: Gillnet, Set, River Rod & Reel (unspecified) Dip Net Licence Area: SAWMILL CREEK TO TEXAS CREEK; THOMPSON RIVER TO BONAPARTE RIVER Maximum Harvest 800 Pieces (dead) Amount: Additional Descriptions: Fishing is permitted in the following areas: 1. In the waters of the Fraser River: (i) From Sawmill Creek to Williams Creek, (ii) From Petch Creek to Texas Creek. 2. -

2021-06-09 Coldwater Indian Band

Hearing Order MH-032-2020 Board File: OF-Fac-Oil-T260-2013-03 61 CANADA ENERGY REGULATOR IN THE MATTER OF the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, SC 2019, c 28, s 10, as amended, (the “CER Act”) and regulations made thereunder; and IN THE MATTER OF an application by Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC (“Trans Mountain”) pursuant to s. 190 of the CER Act to vary the approved pipeline corridor for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project (the “Project”) approved under Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity OC-065 (“Certificate”) Final Argument of Coldwater Indian Band June 9, 2021 TO: The Secretary Canada Energy Regulator Suite 210-517 Tenth Avenue SW Calgary, Alberta T2R 0A8 02013296 Table of Contents PART 1 - OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................... 1 PART 2 - FACTS............................................................................................................................ 2 A. Coldwater’s Aboriginal and Reserve Interests in the Coldwater Valley ............................ 2 1. Extensive Use of Coldwater Valley ................................................................................ 2 2. Coldwater Reserves ........................................................................................................ 4 B. The West Alternative Avoids Risks to Coldwater’s Drinking Water ................................. 5 C. Coldwater Has Been Seeking a Route Change for Several Years ...................................... 6 D. Other Impacts Reduced -

Coldwater Indian Band

Appendix B.10 – Coldwater Indian Band I - Background Information The Coldwater Indian Band (Coldwater) is part of the Nlaka’pamux (pronounced “Ing-khla-kap-muh”) people, whose asserted traditional territory encompasses part of south central British Columbia (BC) from the northern United States to north of Kamloops. Coldwater holds three reserves situated near Merritt and/or the banks of the Coldwater River: Coldwater Indian Reserve no. 1 (1,838 hectares [ha]), Gwen Lake Indian Reserve no. 3 (17 ha) and Paul’s Basin Indian Reserve no. 2 (646 ha). Coldwater’s registered population is approximately 330 members living on Coldwater’s reserve lands, 54 members living on other reserves and 455 living off reserve for a total registered population of 840. Coldwater is part of what was historically called Cawa'xamux or Tcawa'xamux (“people of the creek"), or the Nicola section of the upper Nlaka’pamux peoples, originating from a number of Cawa'xamux village communities. The Nicola Athapaskan speaking people of this region (called by the Nlaka’pamux: Stuwixamux) lived in this vicinity during the early 19th century. Coldwater is a member of the Nicola Tribal Association which also includes: Siska Indian Band, Nicomen Indian Band, Shackan Indian Band, Nooaitch Indian Band, Cook’s Ferry Indian Band and Upper Nicola Band. Coldwater members historically spoke Nłeʔkepmxcín or the language of the Stuwixamux. The former is the language of the Nlaka’pamux people, which falls into the Interior Salish language group. Coldwater is a party to the Nlaka’pamux Nation’s Writ of Summons, which was filed in the BC Supreme Court on December 10, 2003, asserting Aboriginal title to a territory identified in the writ. -

Everybody Has a Piece of the Puzzle Citxw Nlaka’Pamux Assembly Elders and Youth Roundtables Findings Report

Everybody has a Piece of the Puzzle Citxw Nlaka’pamux Assembly Elders and Youth Roundtables Findings Report July 2016 Harold Tarbell / Beverley O'Neil ABOUT THE CITXW NLAKA’PAMUX ASSEMBLY The Citxw Nlaka’pamux Assembly (CNA) was formed for the purpose of managing and administering the Ashcroft Indian Band, Boston Bar First Nation, Coldwater Indian Band, Cook’s Ferry Indian Band, Nicomen Indian Band, Nooaitch Indian Band, Shackan Indian Band and Siska Indian Band (Participating Bands’) commitments in the Participation Agreement and Economic Community Development Agreement as well as overseeing the Nlaka’pamux Trust and Trust distributions. (www.cna-trust.ca) The Consulting Team This project was performed by Harold Tarbell (Mohawk) of Tarbell Facilitation Network (www.tarbell.ca) and Beverley O’Neil (Ktunaxa) of O’Neil Marketing & Consulting (www.designingnations.com). Each consultant has more than 25 years of experience working with First Nations and Indigenous groups with building strategies, research, and economic development. Citxw Nlaka’pamux Assembly Everyone has a Piece of the Puzzle: Elders and Youth Roundtables Findings Report Contents 1 Introduction – How We Got Here .................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 CNA Participating Bands Profile – A Snapshot .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Population ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

2017 Annual Report

LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION PROGRAM Con't... The Elders/Speakers: One of the most important activities taken on by the Language Team continues to be the audio and video taping of Elders/Speakers. In 2017, the following individuals have contributed to the audio and video recordings, as well as attending other cultural activities: • Coldwater – Larry and Ellen Antoine, Annie Major and Bernice Garcia; • Nooaitch – Arthur Sam and Esther Voght, and Amelia Washington; • Shackan – Jim Toodlican and Bert Seymour; • Cooks Ferry – Marie Anderson, Ross Albert, Dempsey Albert, Pearl Hewitt and Verna Miller; • Ashcroft – Leslie Edmonds; • Nicomen – Lorraine Spence; • Siska – Maurice Michell and Ina Dunstan; • Boston Bar – (teaching at Boston Bar School) Charon Spinks; and • Lytton – Wesley and Mary Williams. The Team has developed a “speaker of the Month” profile format and has done some additional interviews with Elders/Speakers. The intent is to interview other speakers who consent to the placing of their profiles on the CNA web site as well as in NLX Radio. CAN-8 Language Program Update: Between February and March of 2017, CAN-8 was launched in Ashcroft, Cooks Ferry, and Coldwater communities; while the remaining 5 Bands launched later in the spring. Each of the Participating Bands was sent a letter to Chief and Council and the Band Administrator to decide where their community wanted to place their six language computers. Some Bands wished to put the computers into schools, others in their Band Office and or Hall. 2017 CNA Annual Report 31 LANGUAGE -

Commitment Tracking Table - Part B - Version 24 Commitment Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Crown Consultaton - Table B - Version 24 - June 7, 2021

6/4/2021 Condition 6 Commitment Tracking Table - Part B - Version 24 Commitment Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Crown Consultaon - Table B - Version 24 - June 7, 2021 Project Stage Commitment Status Prior to Construcon To be completed prior to construcon of specific facility or relevant secon of pipeline Scoping Work has not commenced During Construcon To be completed during construcon of specific facility or relevant secon of pipeline In Progress Work has commenced or is parally complete Prior to Operaons To be completed prior to commencing operaons Superseded by Condion Commitment has been superseded by NEB, BC EAO condion, legal/regulatory requirement Operaons To be completed aer operaons have commenced, including post-construcon monitoring condions Complete Commitment has been met Project Lifecycle Ongoing commitment Superseded by Management Plan Addressed by Trans Mountain Policy or plans, procedures, documents developed for Project No Longer Applicable Change in project design or execuon Superseded by TMEP Noficaon Task Force Program Addressed by the project specific Noficaon Task Force Program No Longer Applicable Change in project design or execuon Note: Red text indicates a change in Commitment Status or a new Commitment, from the previously filed version Addressed by Construcon Line List and Construcon / Environmental As indicated Alignment Sheets Project Stage for Approach to Commitment Team Responsible for Source(s) of Commitment Superseded by Condion (x) Commitment Made To Commitment Descripon Implementaon of Address Criteria to Determine Compleon Addional Comments ID Commitment Commitment Status Number Commitment Commitment 4058 Environment Adams Lake Indian Band Trans Mountain commits to collaborang with Adams Lake to Adams Lake Indian Prior to Construcon Complete Meengs, 1. -

Archaeological Baseline Report

Appendix 9.1-A Ajax Project: Archaeological Baseline Report AJAX PROJECT Environmental Assessment Certificate Application / Environmental Impact Statement for a Comprehensive Study Prepared for: AJAX PROJECT Archaeological Baseline Report May 2015 The world’s leading sustainability consultancy KGHM Ajax Mining Inc. AJAX PROJECT Archaeological Baseline Report May 2015 Project #0241224-0003 Citation: ERM. 2015. Ajax Project: Archaeological Baseline Report. Prepared for KGHM Ajax Mining Inc. by ERM Consultants Canada Ltd.: Vancouver, British Columbia. ERM ERM Building, 15th Floor 1111 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6E 2J3 T: (604) 689-9460 F: (604) 687-4277 ERM prepared this report for the sole and exclusive benefit of, and use by, KGHM Ajax Mining Inc. Notwithstanding delivery of this report by ERM or KGHM Ajax Mining Inc. to any third party, any copy of this report provided to a third party is provided for informational purposes only, without the right to rely upon the report. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This archaeology baseline report summarizes the results of the archaeological studies conducted for the proposed Ajax Project. This report is not an interim or final Heritage Inspection Permit report and is intended to be available to the public. As such, information is presented in this report in a manner consistent with the requirements for confidentiality of archaeological site data in the British Columbia Heritage Conservation Act (HCA; 1996). A greater level of detail can be found in the final reports for Heritage Inspection Permits 2009-0349 and 2014-0171 (ERM Forthcoming a; Morin 2014). The archaeological studies focussed on archaeological resources predating 1846 AD (ERM Forthcoming a; Morin 2014). -

Data Compilation Plan to Support Numerical Flow Modelling Strategy Nicola River Project

REPORT DATA COMPILATION PLAN TO SUPPORT NUMERICAL FLOW MODELLING STRATEGY NICOLA RIVER PROJECT Submitted to: Fraser Basin Council Submitted by: Golder Associates Ltd. 929 McGill Road, Kamloops, British Columbia, V2C 6E9, Canada +1 250 828 6116 1898888-001-R-Rev0 28 June 2018 28 June 2018 1898888-001-R-Rev0 Distribution List 1 copy - Fraser Basin Council i 28 June 2018 1898888-001-R-Rev0 Executive Summary Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) was retained by the Fraser Basin Council to compile and analyse existing data to develop a conceptual hydrogeological model for the Nicola watershed. The general study area includes the Nicola Valley from Nicola Lake downstream to Spences Bridge, the Coldwater River valley from the Coquihalla Highway crossing to the City of Merritt and the lower part of Guichon Creek encompassing the Nicola-Mameet Indian Reserve (NMIR) and the community of Lower Nicola. This study is the second phase of effort to ultimately develop a groundwater flow model for the unconsolidated valley bottom areas within the Nicola Watershed. The valley bottoms generally represent areas of the highest groundwater availability, greatest groundwater use and highest environmental flow needs. The Nicola watershed contains broad, deep valleys and thick quaternary sediments resulting from at least two major periods of non-glacial sedimentation and two distinct periods of glaciation. Near-surface Quaternary valley bottom deposits primarily consist of modern alluvium and fan deposits near present-day elevations. The unconfined Upper Merritt Aquifer is thought to have formed by the Coldwater River eroding glacial lake sediments and backfilling sand and gravel. Post glacial alluvium at Merritt is mapped as continuous with alluvium extending up the Coldwater Valley, alongside the Nicola River from Merritt to Nicola Lake and downriver from Merritt towards Spences Bridge (Fulton 1975). -

Boothroyd Band

Appendix B.9 – Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council I – Background Information The Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council (NNTC) was established in the early 1980s to protect and promote the title and rights of the Nlaka’pamux Nation. The NNTC website states that “Nlaka’pamux title and rights are communal in nature and are shared by all members of the Nation. With our title and rights comes the responsibility to care for the land and resources for future generations1”. The NNTC members include Boothroyd Indian Band, Oregon Jack Creek Indian Band, Lytton First Nation, Spuzzum First Nation, Skuppah Indian Band and Boston Bar First Nation. NNTC was consulted on behalf of Boothroyd Indian Band, Oregon Jack Creek Indian Band, Lytton First Nation, Spuzzum First Nation, and Skuppah Indian Band, and therefore they are considered collectively in this appendix. Boston Bar First Nation was consulted separately and is discussed in a separate appendix. The Nlaka’pamux (pronounced “Ing-khla-kap-muh”) people, whose asserted traditional territory encompasses part of south central British Columbia (BC) from the northern United States to north of Kamloops. The NNTC member bands are a party to the Nlaka’pamux Nation’s Writ of Summons, which was filed in the BC Supreme Court on December 10, 2003, asserting a traditional territory identified in the writ. The Writ of Summons also includes Lower Nicola Indian Band, Ashcroft Indian Band, Coldwater Indian Band, Cook’s Ferry Indian Band, Nicomen Indian Band, Nooaitch Indian Band, Shackan First Nation and Siska Indian Band. The Crown reviewed this Report and appendix with the NNTC at a meeting on November 15, 2016.