Understanding 'Left Behind' Neighbourhoods a Visual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

Connecting Communities: Improving Transport to Get 'Left Behind'

Connecting communities: improving transport to get ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods back on track March 2021 This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees.All-Party-Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the group. This report was researched by OCSI, Campaign for Better Transport, and Local Trust. It was funded by Local Trust, secretariat to the APPG for ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods. Connecting communities: improving transport to get ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods back on track 1 About the All-Party Parliamentary About this report Group for ‘left behind’ The APPG held its fifth evidence session on neighbourhoods 26th January 2021: Buses, broadband and The All-Party Parliamentary Group for ‘left behind’ Beeching – boosting connectivity in ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods is a cross party group of MPs neighbourhoods. This report is a reflection of and Peers. It is committed to improving social that session and the data presented at it. and economic outcomes for residents living in ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods, through the It considered how poor levels of connectivity – development and advocacy of neighbourhood both physical and digital – can contribute to initiatives and policies. an area being ‘left behind’ compounding other disadvantages faced by residents including appg-leftbehindneighbourhoods.org.uk poor health and educational attainment @appgleftbehind and unemployment. The APPG heard how this can make it harder for local people to take About Local Trust sustained action and make improvements to their personal circumstances and their Local Trust is a place-based funder supporting community's prospects. -

MOSSLEY STALYBRIDGE Broadbottom Hollingworth

Tameside.qxp_Tameside 08/07/2019 12:00 Page 1 P 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ST MA A 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Lydgate 0 D GI RY'S R S S D 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A BB RIV K T O E L 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 8 9 SY C R C KES L A O 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 E 8 8 . N Y LAN IT L E E C 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 L 3 3 RN M . HO K R MANCHESTE Hollins 404T000 D R ROAD The Rough 404000 P A A E O Dacres O N HOLM R FIRTH ROAD R A T L E E R D D ANE L N L I KIL O BAN LD O N K O S LAN A A E H R Waterside D - L I E E Slate - Z V T L E D I I L A R R A E Pit Moss F O W R W D U S Y E N E L R D C S A E S D Dove Stone R O Reservoir L M A N E D Q OA R R U E I T C S K E H R C Saddleworth O IN N SPR G A V A A M Moor D M L D I E L A L Quick V O D I R E R Roaches E W I Lower Hollins Plantation E V V I G E R D D E K S C D I N T T U A Q C C L I I R NE R R O A L L Greave T O E T E TAK Dove Stone E M S IN S S I I Quick Edge R Moss D D O A LOWER HEY LA. -

GLOSSOP ROAD, GAMESLEY Transport Assessment

Pendragon Estate Developments Ltd GLOSSOP ROAD, GAMESLEY Transport Assessment 70043297-TA APRIL 2018 CONFIDENTIAL Pendragon Estate Developments Ltd GLOSSOP ROAD, GAMESLEY Transport Assessment TYPE OF DOCUMENT (VERSION) CONFIDENTIAL PROJECT NO. 70043297 OUR REF. NO. 70043297-TA DATE: APRIL 2018 WSP The Victoria 150-182 The Quays Salford, Manchester M50 3SP Phone: +44 161 886 2400 Fax: +44 161 886 2401 WSP.com QUALITY CONTROL Issue/revision First issue Final Revision 2 Revision 3 Remarks Draft Final Date Prepared by D Skinner D Skinner Signature Checked by A Purrier A Purrier Signature Authorised by I Hughes I Hughes Signature Project number 70043297 Report number 1 File reference 70043297-TA GLOSSOP ROAD, GAMESLEY WSP Project No.: 70043297 | Our Ref No.: 70043297-TA April 2018 Pendragon Estate Developments Ltd CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 SCOPING 1 1.3 REPORT STRUCTURE 2 2 POLICY CONTEXT 3 2.1 INTRODUCTION 3 2.2 LOCAL POLICY AND GUIDANCE 3 High Peak Local Plan (HPBC, 2016) 3 High Peak Local Plan Transport Study (DCC, 2014) 4 Derbyshire Local Transport Plan 2011 – 2026 (DCC, 2011) 4 Derbyshire Infrastructure Plan (DCC, 2013) 5 Longdendale Integrated Transport Strategy (Tameside Council, 2009) 5 High Peak Design Guide SPD (HPBC, 2018) 5 2.3 NATIONAL POLICY AND GUIDANCE 6 National Planning Policy Framework (DCLG, 2012) 6 Manual for Streets and Manual for Street 2 – Application of the Wider Principles 6 3 SITE LOCATION AND ACCESSIBILITY 8 3.2 SITE LOCATION AND EXISTING USAGE 8 3.3 SURROUNDING HIGHWAY NETWORK 8 3.4 WALKING LINKS 8 3.5 CYCLING -

The Early Impact of COVID-19 on 'Left Behind' Neighbourhoods

Communities at risk: the early impact of COVID-19 on ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods A ‘data dive’ for the All-Party Parliamentary Group for ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party-Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the group. Communities at risk: the early impact of COVID-19 on ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods 1 About the All-Party Parliamentary Group for ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods About this version The All-Party Parliamentary Group for ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods is a cross party This data dive explores the early impact of 뺭 group of MPs and Peers. It is committed to COVID-19 on ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods improving social and economic outcomes for and was produced to inform the work of the residents living in ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods, All-Party Parliamentary Group for ‘left behind’ through the development and advocacy of neighbourhoods. It builds on the data and neighbourhood initiatives and policies. analysis from Left behind? Understanding communities on the edge released in September appg-leftbehindneighbourhoods.org.uk 2019 by Local Trust. @appgleftbehind Communities at risk: the early impact of COVID-19 on ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods was researched by Oxford Consultants for Social About Local Trust Inclusion (OCSI) and published by Local Trust in July 2020. Local Trust is a place-based funder supporting communities to transform and improve their Local Trust is registered in England and Wales, lives and the places where they live. -

202 341 342 344 Bustimes

25 July 2011 BusTimes Changes since the last edition Bus Numbers Bus 344 Route changed to serve Waverley 202 341 342 Road Estate instead of Grosvenor Road and Marlborough Road. Minor timetable changes. 344 Serving Glossop Simmondley Gamesley Charlesworth Broadbottom Mottram in Longdendale Hattersley Gee Cross Godley Backbower Hyde For public transport information phone Buses run by Traveline on 0871 200 22 33 Speedwellbus 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays Calls cost 10p a minute plus network extras Visit the online bus timetable library at www.tfgm.com ©Transport for Greater Manchester PO Box 429 • Manchester • M60 1HX 28452–G202–5000–0611 Printed on coated recycled paper made using 50% recycled fibre from post consumer sources and 50% virgin fibre from sustainable forests. Further information Mail-out service and alternative formats To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request large print, Braille or recorded information visit www.tfgm.com or phone 0871 200 22 33 Easy access on buses Journeys displaying this symbol in the timetable are run with low floor buses which have no steps at the entrance, making getting on and off easier. Where shown, low floor buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the bus. The bus operator will always try to provide easy access services where these services are scheduled to run. In case of difficulty, please contact the bus operator. Service changes Tickets and information A summary of service changes is available in Bus companies offer a range of tickets for the following places: use on their own buses. -

Display PDF in Separate

NRA Severn-Trent 5 NRA Severn-Trent Region HYDROMETRIC REPORT AND CATALOGUE 1991 National Information Centre The Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive Aztec West BRISTOL BS12 4UD Due for re tu rn En v ir o n m e n t Agency NATIONAL LIBRARY & information service HEAD OFFICE Rio House. Waterside Drive. Aztec West. Almondsbury. Bristol BS32 4UD HYDROMETRIC REPORT & CATALOGUE 1991 NRA National Rivers Authority JULY 1992 Severn-Trent Region Water Resources Section Hydrometric Data Group Sapphire East Streetsbrook Road Solihull B91 1QT Telephone: 021-711-2324 National Rivev- Authority Information O stre Head Offico ENVIRONMENT AGENCY ^^idSS No ............... 099796 Accozz\c'\ 'o IfcCUft............ FOREWORD The 1991 Hydrometric Report and Catalogue is one of a series of annual hydrometric summaries produced by the NRA Severn-Trent Region. It contains a short hydrometric review ofthe year 1991 with a range of data summaries at key sites. The hydrometric catalogue section contains listings of the river level andflow stations, groundwater boreholes, rainfall gauges and climate stations maintained by the region. INTRODUCTION The 1991 Hydrometric Report and Catalogue represents the third published since the National Rivers Authority assumed responsibility for hydrometric data in the Severn- Trent region. The report is designed to give an insight into the type and availability of data that can be obtained from established measurement stations. The catalogue section provides comprehensive lists of these stations with maps to identify their locations. The production of the report and the data it contains represents a combined effort, both from the field hydrometric staff who maintain the stations and undertake vital calibrations, and the staff within the Hydrometric & Data section where the data is processed and archived for future use. -

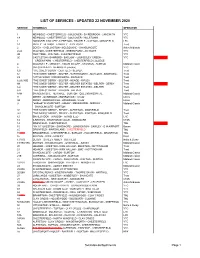

List of Services - Updated 22 November 2020

LIST OF SERVICES - UPDATED 22 NOVEMBER 2020 SERVICE TERMINALS OPERATOR 1 NEWBOLD - CHESTERFIELD - BOLSOVER - SHIREBROOK - LANGWITH YTC 1A NEWBOLD - CHESTERFIELD - BOLSOVER - HILLSTOWN YTC 1 "MANSFIELD MILLER" ALFRETON - TIBSHELF - SUTTON - MANSFIELD LRC 1A RIPLEY - HEANOR - LANGLEY - ALDERCAR Trent 2 DERBY - CHELLASTON - MELBOURNE - SWADLINCOTE Arriva Midlands 2/2A WALTON - CHESTERFIELD - GREEN FARM - ASHGATE YTC 2B YEW TREE - WALTON - CHESTERTFIELD YTC 2C CASTLETON - BAMFORD - BASLOW - LOUNDSLEY GREEN - YTC GREEN FARM - CHESTERFIELD - CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 4 WOODVILLE - MIDWAY - SWADLINCOTE - STANTON - BURTON Midland Classic 5 CHESTERFIELD - NEWBOLD (circular) YTC 6.0 "THE SIXES" DERBY - DUFFIELD - BELPER Trent 6.1 "THE SIXES" DERBY - BELPER - WIRKSWORTH - MATLOCK - BAKEWELL Trent LS "LITTLE SIXES" WIRKSWORTH - MATLOCK Trent 6.2/6.3/6E "THE SIXES" DERBY - BELPER - HEAGE - RIPLEY Trent 6N "THE SIXES" DERBY - BELPER - BELPER ESTATES - BELPER - DERBY Trent 6.4 "THE SIXES" DERBY - BELPER - BELPER ESTATES - BELPER Trent 6.X "THE SIXES" DERBY - KILBURN - BELPER Trent 8/8H SWADLINCOTE - NEWHALL - BURTON - QUEENS HOSPITAL Midland Classic 9 DERBY - OCKBROOK - BORROWASH circular Littles 9A DERBY - BORROWASH - OCKBROOK circular Littles 9 "airline9 " E M AIRPORT - ASHBY - MELBOURNE - MIDWAY - Midland Classic SWADLINCOTE - BURTON 9.1 "THE NINES" DERBY - RIPLEY - ALFRETON - MANSFIELD Trent 9.3 "THE NINES" DERBY - RIPLEY - ALFRETON - PINXTON - MANSFIELD Trent 12 SHIREBROOK - WARSOP - MANSFIELD LRC 14 ILKESTON - STANTON-BY-DALE - SANDIACRE CT4N 14 DRONFIELD -

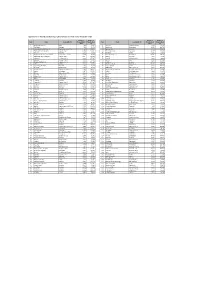

Ward-Based Ranking of Likely Demand for Third Sector Affordable Credit

Appendix One - Ward-Based Ranking of Likely Demand for Third Sector Affordable Credit Number of Number of Number of Number of Rank Ward Local Authority Households in Households in Rank Ward Local Authority Households in Households in Ward LA Ward LA 1 Windmill Hill (Halton) Halton 908 48,765 71 Alloa Mar Clackmannanshire 1,050 21,715 2 Plas Madoc Wrexham 792 56,178 72 Sparkbrook Birmingham 10,065 409,703 3 Orchard Park and Greenwood Kingston upon Hull, City of 5,754 108,074 73 Spinney Hills Leicester 7,124 114,943 4 Parkhead (City of Glasgow) Glasgow, City of 3,704 275,467 74 Bede (Gateshead) Gateshead 4,102 85,496 5 Princess Knowsley 2,319 61,546 75 Pendleton Salford 4,272 95,709 6 Grangetown (Redcar and Cleveland) Redcar and Cleveland 2,129 59,388 76 Aston (Birmingham) Birmingham 11,405 409,703 7 Summerhill (City of Glasgow) Glasgow, City of 2,901 275,467 77 Ward 3 Inverclyde 1,563 36,675 8 Glenwood Glasgow, City of 3,228 275,467 78 Low Hill Wolverhampton 4,682 99,939 9 Barlanark Glasgow, City of 2,960 275,467 79 Bidston Wirral 4,499 137,858 10 Bridgeton/Dalmarnock Glasgow, City of 2,810 275,467 80 Clubmoor Liverpool 4,739 195,216 11 Owton Hartlepool 2,115 39,311 81 Washwood Heath Birmingham 10,182 409,703 12 Queensway (Wrexham) Wrexham 1,103 56,178 82 Linacre (Sefton) Sefton 5,915 118,537 13 Thorntree Middlesbrough 2,472 56,806 83 Wallacewell Glasgow, City of 2,767 275,467 14 Bransholme East Kingston upon Hull, City of 3,794 108,074 84 Shadsworth with Whitebirk Blackburn with Darwen 3,247 54,565 15 Aspley Nottingham 6,247 120,903 85 -

School Bus Services in the Stockport Area Summer 2020

School Bus Services in the Stockport Area Summer 2020 Journeys in this leaflet operate on schooldays only, unless otherwise stated. Although provided primarily for school students, members of the public may use these services with the exception of Yellow School Buses. Services are listed alphabetically under school names. 12/06/2020 Stockport Schools 2019/2020 Page 1 An introduction to School buses and concessionary fares for students in Greater Manchester Passengers can pay a fare to the driver for each journey shown on this timetable. However, students will need to show an IGO pass to travel at the concessionary (reduced) fare. If students do not have an IGO pass, they will have to pay a higher fare. Most of the journeys shown in this timetable are funded by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM). The majority of TfGM funded services charge a standard fare and also offer daily return tickets. In some cases, the return ticket can also be used for travel on other journeys which serve similar areas – even if it is provided by a different operator. On most services, students can also buy a weekly scholar’s ticket, which costs £7.40. These are ONLY valid on schooldays on school buses and are available from the bus driver on all services where they are applicable. To help the driver, please try to have the correct fare when buying your ticket. A summary of fares and ticketing information on all school services included in this timetable can be found at https://www.tfgm.com/tickets-and-passes/bus-school-bus-services There are also a small number of TfGM funded services where the operator sets the fares. -

The London Gazette, 18 April, 1958 2499

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 18 APRIL, 1958 2499 APPOINTMBNTS OF TRUSTEES. SNEJJL, Elizabeth (widow), residing and! carrying on business as a MILK RETAILER under .the style HERBERT, Peter John, lately residing at" Kewstoke," of E. Snell & Sons at The Avenue Dairy, 41. iChatsworth Road, Torquay, Devon, 111, Bucklabury in the county of Berks. Court— Broad Oaks 'Road, Solihull, (Birmingham, NBWBURY. No. of Matter—3 of 1958. Warwickshire, and at 147, Woodlands Road, Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Moseley, Birmingham aforesaid, COMPANY Tickler. Walter Thomas Wells, of 19, Easteheap, SECRETARY, whose last known address was the London, E.C.3, Chartered Accountant. 'Date of Belvedere Hotel, Great Denmark Street, Dublin, Certificate of Appointment— 15th April, 1958. Ireland', but whose present place of residence the Petitioning Creditor is unable to ascertain, a COUPE, Derek, residing at 69A, Melton Road, West domiciled Englishman. Court—HIGH COURT Bridgford, in the county of Nottingham, and OF JUSTICE. No. of Matter—3 of 1959. carrying on .business under the name or style of Trustee's Name, Address and Description.— Avondate Hardware Stores, Avondale Road, Goodman, Frederick, 77, Portland Place, London, Carlton in the county of Nottingham. HARD- W.I, Certified Accountant. Date of Certificate WARE RETAILER. Court—NOTTINGHAM. of Appointment—2nd April, 1958. No. of Matter—7 of 1958. Trustee's Name, Address and Descriptionr-^Maairs, Gordon MILTON, George James, 2, St. Ann's Hill, Wands- Bernard, 8, Oxford Street, Nottingham, Chartered worth, S.W.18, London, of no occupation-, lately Accountant. Date of Certificate of Appointment carrying on business as a STREET (BOOK- —14th April, 1958. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 690 8 March 2021 No. 185 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 8 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 501 8 MARCH 2021 502 Dr Coffey: My hon. Friend should be aware that we House of Commons have account managers working in all parts of the country to take up this scheme. In particular, we continue Monday 8 March 2021 to work with a wide range of organisations closely connected to SMEs, including chambers of commerce and the Federation of Small Businesses, to get the The House met at half-past Two o’clock message out there and make it straightforward to apply. We should recognise that, due to eligibility criteria, not all direct applications may be successful, and the support PRAYERS of a gateway is likely to be beneficial. We are also enabling applications through the gateway plus model, [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] which will particularly help sole traders, and we will continue to advertise that. Virtual participation in proceedings continued (Order, 4 June and 30 December 2020). Peter Gibson [V]: I thank my right hon. Friend for her [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] answer. I welcome the removal of the 30-person threshold, which will help even the smallest firm in my constituency. Since the launch of the kickstart scheme, our phenomenal Oral Answers to Questions Tees Valley Mayor Ben Houchen has been facilitating SMEs to access it, and he has helped 350 young people sign up.