Program Notes by Bruce Whiteman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Kebyart Is More Than Just Four Musicians

The art of kebyar A quartet that is not only extremely Explosive contrasts of tempo, dynamics and colours well composed, and at the top of their game, but also musicians that are capable of moving beyond You have the potential to do These are the qualities that characterise gamelan gong kebyar technical perfection to reach musical anything. You are very sensitive music, when a group of different instruments are played communication.’ and you always give your all together for so long that they become one. The unique virtu- osity and energy of kebyar is adored by the Balinese com- Revista Musical Catalana to music. You are virtuoso.’ munity. Sergio Azzolini The most impressive thing was the agogic flexibility: each new phrase Kebyart, was created organically - playing in sync, the daily endeavour Kebyart, as though they were one - and held together, to create something a never-ending creating a space in which extraordinary Kebyart, unique interest in moments of music are brought to life.’ the search for musical roots excellence Musikdorf Ernen Magazine Kebyart, an explosion of energy and fresh air Kebyart, on stage an open space breathing as one The quartet showed It almost seemed for their profound understanding as if the young gentlemen creativity of the classical genre. were one and the same person, Simplicity, elegance, contrast so much did their musical and humour were the key tools phrases rise and fall in Kebyart, Kebyart, on which their performance a moving harmony, promoting breaking the limits was based. A truly excellent intertwining -

2017–2018 Season Artist Index

2017–2018 Season Artist Index Following is an alphabetical list of artists and ensembles performing in Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage (SA/PS), Zankel Hall (ZH), and Weill Recital Hall (WRH) during Carnegie Hall’s 2017–2018 season. Corresponding concert date(s) and concert titles are also included. For full program information, please refer to the 2017–2018 chronological listing of events. Adès, Thomas 10/15/2017 Thomas Adès and Friends (ZH) Aimard, Pierre-Laurent 3/8/2018 Pierre-Laurent Aimard (SA/PS) Alarm Will Sound 3/16/2018 Alarm Will Sound (ZH) Altstaedt, Nicolas 2/28/2018 Nicolas Altstaedt / Fazil Say (WRH) American Composers Orchestra 12/8/2017 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) 4/6/2018 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) Anderson, Laurie 2/8/2018 Nico Muhly and Friends Investigate the Glass Archive (ZH) Angeli, Paolo 1/26/2018 Paolo Angeli (ZH) Ansell, Steven 4/13/2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra (SA/PS) Apollon Musagète Quartet 2/16/2018 Apollon Musagète Quartet (WRH) Apollo’s Fire 3/22/2018 Apollo’s Fire (ZH) Arcángel 3/17/2018 Andalusian Voices: Carmen Linares, Marina Heredia, and Arcángel (SA/PS) Archibald, Jane 3/25/2018 The English Concert (SA/PS) Argerich, Martha 10/20/2017 Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (SA/PS) 3/22/2018 Itzhak Perlman / Martha Argerich (SA/PS) Artemis Quartet 4/10/2018 Artemis Quartet (ZH) Atwood, Jim 2/27/2018 Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra (SA/PS) Ax, Emanuel 2/22/2018 Emanuel Ax / Leonidas Kavakos / Yo-Yo Ma (SA/PS) 5/10/2018 Emanuel Ax (SA/PS) Babayan, Sergei 3/1/2018 Daniil -

The Time Is Now Thethe Timetime Isis Nownow Music Has the Power to Inspire, to Change Lives, to Illuminate Perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to Shift Our Vantage Point

20/21 SEASON The Time Is Now TheThe TimeTime IsIs NowNow Music has the power to inspire, to change lives, to illuminate perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to shift our vantage point. featuring FESTIVAL Your seats are waiting. Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression An exploration of humankind’s capacity for hope, courage, and resistance in the face of the unimaginable PERSPECTIVES Rhiannon Giddens “… an electrifying artist …” —Smithsonian PERSPECTIVES Yannick Nézet-Séguin “… the greatest generator of energy on the international podium …” —Financial Times PERSPECTIVES Jordi Savall “… a performer of genius but also a conductor, a scholar, a teacher, a concert impresario …” —The New Yorker DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Andrew Norman “… the leading American composer of his generation ...” —Los Angeles Times Left: Youssou NDOUR On the cover: Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla carnegiehall.org/subscribe | 212-247-7800 Photos: NDOUR by Jack Vartoogian, Gražinytė-Tyla by Benjamin Ealovega. Box Office at 57th and Seventh Rafael Pulido Some of the most truly inspiring music CONTENTS you’ll hear this season—or any other season—at Carnegie Hall was written in response to oppressive forces that have 3 ORCHESTRAS ORCHESTRAS darkened the human experience throughout history. Perspectives: Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression takes audiences Yannick Nézet-Séguin on a journey unique among our festivals for the breadth of music 12 these courageous artists employed—from symphonies to jazz to Debs Composer’s popular songs and more. This music raises the question of why, 13 Chair: Andrew Norman no matter how horrific the circumstances, artists are nonetheless compelled to create art; and how, despite those circumstances, 28 Zankel Hall Center Stage the art they create can be so elevating. -

20Th May - 14Th June Welcome 2

1 20th May - 14th June Welcome 2 Welcome to the May / June 2021 West Wicklow Festival! I am thrilled that the festival is delivering such a superb programme, featuring so many incredibly talented and exciting artists, all for free online, in tip top HD quality. Of course we all desperately miss live audiences, but I hope the quality of the recordings will make everyone feel that the concert hall experience has been welcomed into their own home! It has been a huge challenge to organise this year’s festival with many extra obstacles, but I hope that everyone will enjoy the final product, into which, all involved, have poured their hearts and souls. A huge thank you to all of our public and private patrons for their invaluable support.If you are in a position to make a donation to support our festival charity please consider doing so. Enjoy the concerts and I look forward to being re-united with you all in Wicklow soon! Fiachra Garvey Founder and Artistic Director Programme 3 Thursday 20th May 2021, 8pm Notes Ian Fox 2021 Rachel Kelly (mezzo-soprano) Fiachra Garvey (piano) Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Après un rêve Claude Debussy (1862-1918) C’est L’extase langoureuse Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) À Chloris Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) L’île inconnue Rachel and Fiachra begin with four famous chansons or French art songs. Gabriel Fauré wrote Après un rêve in the 1870s and it was published in 1878. Later it was incorporated into an edition of three songs and published as Opus 7. -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

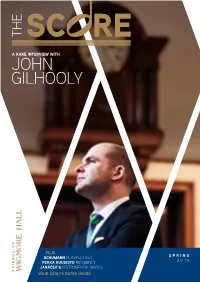

John Gilhooly

A RARE INTERVIEW WITH JOHN GILHOOLY PLUS SPRING SCHUMANN PERSPECTIVES 2018 PEKKA KUUSISTO RESIDENCY JAN ÁČEK’S INSTRUMENTAL WORKS FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS YOUR 2018/19 DATES INSIDE John Gilhooly’s vision for Wigmore Hall extends far into the next decade and beyond. He outlines further dynamic plans to develop artistic quality, financial stability and audience diversity. JOHN GILHOOLY IN CONVERSATION WITH CLASSICAL MUSIC JOURNALIST, ANDY STEWART. FUTURE COMMITMENT “I’M IN FOR THE LONG HAUL!” Wigmore Hall’s Chief Executive and Artistic Director delivers the makings of a modern manifesto in eight words. “This is no longer a hall for hire,” says John Gilhooly, “or at least, very rarely”. The headline leads to a summary of the new season, its themed concerts, special projects, artist residencies and Learning events, programmed in partnership with an array of world-class artists and promoted by Wigmore Hall. It also prefaces a statement of intent by a well-liked, creative leader committed to remain in post throughout the next decade, determined to realise a long list of plans and priorities. “I am excited about the future,” says John, “and I am very grateful for the ongoing help and support of the loyal audience who have done so much already, especially in the past 15 years.” 2 WWW.WIGMORE-HALL.ORG.UK | FRIENDS OFFICE 020 7258 8230 ‘ The Hall is a magical place. I love it. I love the artists, © Kaupo Kikkas © Kaupo the music, the staff and the A glance at next audience. There are so many John’s plans for season’s highlights the Hall pave the confirms the strength characters who add to the way for another 15 and quality of an colour and complexion of the years of success. -

Mcgill CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Boris Brott, Artistic Director Taras Kulish, Executive Director

sm19-7_EN_p01_Cover_sm19-1_FR_pXX 14-05-28 2:25 PM Page 1 sm19-7_EN_p02_ADs_sm19-1_FR_pXX 14-05-28 11:16 AM Page 2 DON’T LEAVE SCHOOL WITHOUT IT! Special La Scena Musicale Subscription for Students ONLY INFO: 514.948.2520 $25 [email protected] • www.scena.org TERRA INCOGNITA Arturo Parra THE GUITARIST AND COMPOSER “Seven magnificent portraits in sound... Great art!” – Mario Paquet, ESPACE MUSIQUE “A journey to inner landscapes replete with impenetrable mysteries...” – ResMusica (FRANCE) AGE WWW.LAGRENOUILLEHIRSUTE.COM July 22 August 12 NEW – Tour de France TrioALBUM Arkaède Emerson String Quartet Beatrice Rana, piano Orion Quartet with Peter Serkin Modigliani String Quartet Sondra Radvanovsky Miloš Toronto Symphony Orchestra Isabelle Fournier, Violin / Viola Julien LeBlanc, Piano TORONTOSUMMERMUSIC.COM Karin Aurell, Flute www.leaf-music.ca sm19-7_EN_p03_AD-ottawachamberfest_sm19-1_FR_pXX 14-05-27 7:02 PM Page 3 CHAMBERFEST JULY 24 JUILLET AUGUST 07 AOÛT OTTAWA OTTAWA INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE MUSIQUE DE CHAMBRE D’OTTAWA SONDRA RADVANOVSKY IN RECITAL TUESDAY 29 JULY 7:00PM One of the preeminent Verdian sopranos of her generation performs a rare and intimate recital. TOP 100 LEVEL OF DISTINCTION FESTIVAL HIGHLIGHTS A FAR CRY JANINA FIALKOWSKA IL TRIONFO DEL TEMPO FRIDAY 25 JULY 7:00PM FRIDAY 01 AUGUST 7:00PM TUESDAY 05 AUGUST 7:00PM ONFESTIVAL SALE PASSES AND NOW! TICKETS 613.234.6306CHAMBERFEST.COM/TICKETS LSM-English-Chamberfest2014.indd 1 23/05/2014 10:30:33 AM sm19-7_EN_p04-6_Orford_sm19-1_FR_pXX 14-05-30 11:23 AM Page 4 “Everyone finds their voice in the ensemble, and by playing together, they tend to pick up certain traits from each other that help the whole become more blended.” PLAYING theNEW ORFORD STRING QUARTET WELL TOGETHER by L.H. -

Giacomo Puccini’S Chamber Music Is Perhaps Less Familiar to the Wider Audience

BIOGRAPHY Noûs (nùs) is an ancient greek word whose meaning is mind and therefore rationality, but also inspiration CONWAY and creativity. THE QUARTETTO NOÛS, composed of four young Italian musicians, was founded in 2011 at the Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana in Lugano. The quartet received its training at HALL the Accademia “Walter Stauffer” in Cremona in the class of the Quartetto di Cremona, at the Musik SUNDAY Akademie in Basel in the class of Professor Reiner Schmidt (Hagen Quartet) and also studied with internationally renowned Professors like Hatto Beyerle (Alban Berg Quartet) and Aldo Campagnari CONCERTS (Quartetto Prometeo). It is currently attending the Musikhochschule Lübeck in the class of Professor Heime Müller (Artemis Quartet) and the Escuela Superior de Música “Reina Sofia” in Madrid in the Günter Pichler’s class (Alban Berg Quartett). The quartet won the first prize at the “Luigi Nono” International Competition in Venaria Reale, Turin, and at the XXI “Anemos International Competition” in Rome. In Patrons 2014 it was awarded an honorable mention at the “Sony Classical Talent Scout” in Madesimo, Italy. - Stephen Hough, Laura Ponsonby AGSM, Prunella Scales CBE, Roderick Swanston, Hiro Takenouchi and Timothy West CBE It received from La Fenice Theatre in Venice the “Arthur Rubinstein - Una Vita nella Musica 2015” Artistic Director - Simon Callaghan Award for revealing itself in a few years as one of the most promising Italian chamber music group and for showing in his still brief career to be able to approach the great literature for string quartet in a mature manner, seeking a reasoned and not ephemeral interpretation in the masterpieces of the classic- romantic period and of the twentieth century, continuing at the same time a serious and not episodic research even within the language of the contemporary music. -

Amihai Grosz Viola

„His tone is confident and passionate, he is an eloquent narrator without words, sovereignly covering the melancholic-dreamy width of the score.“ Frederik Hanssen, Der Tagesspiegel AMIHAI GROSZ VIOLA Amihai Grosz looks back on a very unusual career path: At first a quartet player (founding member of the Jerusalem Quartet), then and until today Principal Violist with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, and also a renowned soloist. Initially, Amihai Grosz learned to play the violin, before switching to the viola at age 11. In Jerusalem, he was taught by David Chen, later by Tabea Zimmermann in Frankfurt and Berlin as well as in Tel Aviv by Haim Taub, who had a formative influence on him. At a very early age, he received various grants and prizes and was a member of the “Young Musicians Group” of the Jerusalem Music Center, a program for outstanding young musical talents. As a soloist Grosz has collaborated with renowned conductors such as Zubin Mehta, Tugan Sokhiev, Ariel Zukermann, Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon Rattle, Alexander Vedernikov and Gerard Korsten and performs internationally with orchestras such as the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestre d'Auvergne and the Zurich Chamber Orchestra. In the world of chamber music, Amihai Grosz performs with artists such as Yefim Bronfman, Mitsuko Uchida, Daniel Hope & Friends, Eric le Sage, Janine Jansen & Friends, Julian Steckel, Daishin Kashimoto and David Geringas. Internationally, he can be heard regularly at the most prestigious concert halls such as the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Tonhalle Zurich, Wigmore Hall in London and the Philharmonie Luxembourg, as well as at leading festivals including the Jerusalem Chamber Music Festival, the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, the Evian, Verbier and Delft Festivals, the BBC Proms and the Utrecht International Chamber Music Festival.