A Feminist Perspective on Multicultural Children's Literature In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2009

Annual Report 2009 Digitization INNOVATION CultureFREEDOM CommitmentChange Bertelsmann Annual Report 2009 CreativityEntertainment High-quality journalism Performance Services Independence ResponsibilityFlexibility BESTSELLERS ENTREPRENEURSHIP InternationalityValues Inspiration Sales expertise Continuity Media PartnershipQUALITY PublishingCitizenship companies Tradition Future Strong roots are essential for a company to prosper and grow. Bertelsmann’s roots go back to 1835, when Carl Bertelsmann, a printer and bookbinder, founded C. Bertelsmann Verlag. Over the past 175 years, what began as a small Protestant Christian publishing house has grown into a leading global media and services group. As media and communication channels, technology and customer needs have changed over the years, Bertelsmann has modifi ed its products, brands and services, without losing its corporate identity. In 2010, Bertelsmann is celebrating its 175-year history of entrepreneurship, creativity, corporate responsibility and partnership, values that shape our identity and equip us well to meet the challenges of the future. This anniver- sary, accordingly, is being celebrated under the heading “175 Years of Bertelsmann – The Legacy for Our Future.” Bertelsmann at a Glance Key Figures (IFRS) in € millions 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Business Development Consolidated revenues 15,364 16,249 16,191 19,297 17,890 Operating EBIT 1,424 1,575 1,717 1,867 1,610 Operating EBITDA 2,003 2,138 2,292 2,548 2,274 Return on sales in percent1) 9.3 9.7 10.6 9.7 9.0 Bertelsmann Value -

Volk, Devils and Moral Panics in White South Africa, 1976 - 1993

The Devil’s Children: Volk, Devils and Moral Panics in White South Africa, 1976 - 1993 by Danielle Dunbar Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Sandra Swart Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences March 2012 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2012 Copyright © 2012 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT There are moments in history where the threat of Satanism and the Devil have been prompted by, and in turn stimulated, social anxiety. This thesis considers particular moments of ‘satanic panic’ in South Africa as moral panics during which social boundaries were challenged, patrolled and renegotiated through public debate in the media. While the decade of the 1980s was marked by successive states of emergency and the deterioration of apartheid, it began and ended with widespread alarm that Satan was making a bid for the control of white South Africa. Half-truths, rumour and fantasy mobilised by interest groups fuelled public uproar over the satanic menace – a threat deemed the enemy of white South Africa. -

Diss. Football Finance

Literaturverzeichnis 265 Literaturverzeichnis Adams, Michael (1991): Eigentum, Kontrolle und Beschränkte Haftung. 1. Aufl. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft Adler, Moshe (1985): Stardom and Talent, in: The American Economic Review, Vol. 75, S. 208-212 Ahlers, Erich (2000a): Der Abstieg als Schadensfall. Nur wenige Bundesliga-Klubs versichern sich gegen die Folgen eines sportlichen Absturzes, in: Handelsblatt, 1./2. Dezember, Nr. 233, S. 51 Ahlers, Erich (2000b): DFB-Börsenaufsicht glaubt an das Reinheitsgebot. Bundesliga-Spieler sollen gegen die Statuten des Verbandes verstoßen und Aktien von Borussia Dortmund gekauft haben, in: Handelsblatt, 22./23. Dezember, Nr. 248, S. 49 Ahlers, Erich (2001a): Microsoft vor Augen. Die Fußball-Kleinanbieter aus Unterhaching haben durchaus Visionen, in: Handelsblatt, Finanzcheck Handelsblatt-Serie: Wenn Fußballvereine zu Unternehmen werden, 9. Mai, Nr. 89, S. 48 Ahlers, Erich (2001b): Im Klub der kleinen Kaiser. Beim FC Bayern München ist jeder ein Star – und dem Entertainment verpflichtet, in: Handelsblatt, Finanzcheck Handelsblatt - Serie: Wenn Fußballvereine zu Unternehmen werden, 23. Mai, Nr. 99, S. 48 Ahlers, Erich (2001c): Frieden auf dem Flur. Wie der HSV und die Vermarkter von UfA Sports immer öfter auf einen Nenner kommen, in: Handelsblatt, 22. August, Nr. 151, S. 36 Ahlers, Erich/Thylmann, Marc (2001): Amoroso amortisiert sich. Borussia Dortmund gewinnt und gewinnt – jetzt auch an der Börse mit der Aktie Schwarz-Gelb, in: Handelsblatt, 24./25. August, Nr. 163, S. 44 Akerlof, George A. (1970): The Market for „Lemons“. Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism, in: Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 84, S. 488-500 Akerlof, George A. (1976): The Economics of Caste and of the Rat Race and other Woeful Tales, in: Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. -

A New Model for Scientific Publications: a Managing Editor's View

A new model for scientific publications: A Managing Editor’s view OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1 (2020), 220-245: THE POLICY OF CULTURAL RIGHTS: STATE REGULATION, SOCIAL CONTESTATION AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1112 RECEIVED 09 DECEMBER 2019, ACCEPTED 07 FEBRUARY 2020 LEIRE KORTABARRIA, MANAGING EDITOR∗ Abstract In this essay, we will first set out the context in which Oñati Socio-Legal Series was created. We will then aim to offer a non-exhaustive view of what an open access journal is and what it implies for scholars and for publishers, and the, sometimes, stark differences in each one’s view. From here, we will move on to draw a succinct description of the implications of the mainstream journal publishing scheme, with a stress on the commercial and economic implications. We will then narrow the focus and zero in on the case of Oñati Socio-Legal Series. Drawing on the case of this journal, we will argue why it is possible to expand a 100% free Open Access journal model, with no charges whatsoever on the authors, and why it is necessary for the scientific community. Key words Open Access; Oñati Socio-Legal Series; journals; IISL This paper is a development of a presentation titled Story of a (Unique) Journal: ‘Oñati Socio-Legal Series', given by Leire Kortabarria at the Linking Generations for Global Justice International Law and Society Congress, celebrated at the IISL, in Oñati (Spain), between 19 and 21 June 2019. The author wishes to thank and acknowledge the work -

Feminist Presses and Publishing Politics in Twentieth-Century Britain

MIXED MEDIA: FEMINIST PRESSES AND PUBLISHING POLITICS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN SIMONE ELIZABETH MURRAY DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 1999 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author U,Ip 1 Still, Madam, the private printing press is an actual fact, and not beyond the reach of a moderate income. Typewriters and duplicators are actual facts and even cheaper. By using these cheap and so far unforbidden instruments you can at once rid yourself of the pressure of boards, policies and editors. They will speak your own mind, in your own words, at your own time, at your own length, at your own bidding. And that, we are agreed, is our definition of 'intellectual liberty'. - Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas (1938) 2 Image removed due to third party copyright ABSTRACT The high cultural profile of contemporary feminist publishing in Britain has previously met with a curiously evasive response from those spheres of academic discourse in which it might be expected to figure: women's studies, while asserting the innate politicality of all communication, has tended to overlook the subject of publishing in favour of less materialist cultural modes; while publishing studies has conventionally overlooked the significance of gender as a differential in analysing print media. Siting itself at this largely unexplored academic juncture, the thesis analyses the complex interaction of feminist politics and fiction publishing in twentieth-century Britain. Chapter 1 -" 'Books With Bite': Virago Press and the Politics of Feminist Conversion" - focuses on Britain's oldest extant women's publishing venture, Virago Press, and analyses the organisational structures and innovative marketing strategies which engineered the success of its reprint and original fiction lists. -

The Author Was Never Dead

THE AUTHOR WAS NEVER DEAD: How Social Media and the Online Literary Community Altered the Visibility of the Translated Author in America Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, MA Undergraduate Program in Independent Interdisciplinary Major (Communication and Literature Studies) Elizabeth Bradfield, Advisor David Sherman, Second Reader In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Emily Botto April 2020 Copyright by Emily Botto Botto 2020 Abstract The American publishing industry is notorious for its disinterest in translation. Although its notoriety has made most publishers very aware of the absence of translated literature in America, its perception as an unprofitable venture has prevented publishing houses from investing in the genre and thereby improving the small number of published translations. This thesis explores the possible ways in which translated authors and their readers can alter this perception by utilizing recent technological advances in global social networking. “The Author Was Never Dead” will cover the history of and current environment surrounding literary translation in the U.S. including which translated novels have become successful and how that relates to the visibility of the translated author. Researching the slow growth in the visibility of the translated author and their cultural ambassadors on social media and online communities provides insight into how and why a translated book can gain popularity in a country known for its literary ethnocentrism. Acknowledgments Thanks to my amazing advisor, Elizabeth Bradfield, for always making time for me, answering my questions, and following my logic even when it threatened to fall out the window. -

Canadian Literature Versita Discipline: Language, Literature

Edited by Pilar Somacarrera Made in Canada, Read in Spain: Essays on the Translation and Circulation of English- Canadian Literature Versita Discipline: Language, Literature Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Language Editor: Barry Keane Published by Versita, Versita Ltd, 78 York Street, London W1H 1DP, Great Britain. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the authors. Copyright © 2013 Pilar Somacarrera for Chapters 1, 5 and 6; Nieves Pascual for chapter 2; Belén Martín-Lucas for chapter 3; Isabel Alonso-Breto and Marta Ortega-Sáez for chapter 4; Mercedes Díaz-Dueñas for chapter 7 and Eva Darias- Beautell for chapter 8. ISBN (paperback): 978-83-7656-015-1 ISBN (hardcover): 978-83-7656-016-8 ISBN (for electronic copy): 978-83-7656-017-5 Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Language Editor: Barry Keane www.versita.com Cover illustration: ©iStockphoto.com/alengo Contents Acknowledgments ..............................................................................................8 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1 Contextual and Institutional Coordinates of the Transference of Anglo-Canadian Literature into Spain / Pilar Somacarrera ........... 21 1. A Terra Incognita Becomes Known .................................................................................21 2. Translation, the Literary Field and -

The Encyclopedia of New Religions Bibliography

The Encyclopedia of New Religions Bibliography The following bibliography has been constructed to enable readers to explore selected topics in greater depth. Rather than present a long uncategorized list, which would have been unhelpful and potentially confusing, the classification of literature mirrors the format of the book. (Classifying new religions and spiritualities is a notoriously difficult problem, and it should not be thought that groups that have been bracketed together do not have important differences.) In a few instances a movement may be relevant to more than one section; hence readers are advised to look in other sections if they cannot instantly locate the sought material. Anyone who compiles a bibliography on new spiritualities has to make choices, since there is a vast array of literature available. While endeavouring to include a good range of material and viewpoints, we have omitted material that we consider to be badly inaccurate or misleading. However, some religious movements have been virtually neglected by writers and hence the material indicated below is the best available. For some groups there is virtually no literature apart from their own writings. While we have aimed to incorporate material on the grounds of accessibility, quality, up-to-dateness, popularity and prominence, inclusion here does not necessarily imply endorsement by the editor or individual authors. At the end of each section a selection of websites has been provided. However, it should be noted that, whilst these were all available at the time of writing, and whilst we believe them to be relatively reliable, unlike books, websites can literally disappear overnight. -

2020 Financial Statements for Bertelsmann SE & Co. Kgaa

Financial Statements and Combined Management Report Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA, Gütersloh December 31, 2020 Contents Balance sheet Income statement Notes to the financial statements Combined Management Report Responsibility Statement Auditor’s report 1 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Assets as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Non-current assets Intangible assets Acquired industrial property rights and similar rights as well as licenses to such rights 1 9 8 9 8 Tangible assets Land, rights equivalent to land and buildings 1 306 311 Technical equipment and machinery 1 1 1 Other equipment, fixtures, furniture and office equipment 1 42 47 Advance payments and construction in progress 1 7 2 356 361 Financial assets Investments in affiliated companies 1 15,974 14,960 Loans to affiliated companies 1 230 712 Investments 1 - - Non-current securities 1 1,461 1,252 17,665 16,924 18,030 17,293 Current assets Receivables and other assets Accounts receivable from affiliated companies 2 4,893 4,392 Other assets 2 94 148 4,987 4,540 Securities Other securities - - Cash on hand and bank balances 3 2,476 513 7,463 5,053 Prepaid expenses and deferred charges 4 20 20 25,513 22,366 2 Equity and liabilities as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Equity Subscribed capital 5 1,000 1,000 Capital reserve 2,600 2,600 Retained earnings Legal reserve 100 100 Other retained earnings 6 5,685 5,485 5,785 5,585 Net retained profits 898 663 10,283 9,848 Provisions Provisions for pensions and similar obligations 7 377 357 Provision -

Typical Girls: the Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips Susan E

Typical girls The Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips Susan E. Kirtley TYPICAL GIRLS STUDIES IN COMICS AND CARTOONS Jared Gardner and Charles Hatfield, Series Editors TYPICAL GIRLS The Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips SUSAN E. KIRTLEY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS COPYRIGHT © 2021 BY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY. THIS EDITION LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL-NODERIVS LICENSE. THE VARIOUS CHARACTERS, LOGOS, AND OTHER TRADEMARKS APPEARING IN THIS BOOK ARE THE PROPERTY OF THEIR RESPECTIVE OWNERS AND ARE PRESENTED HERE STRICTLY FOR SCHOLARLY ANALYSIS. NO INFRINGEMENT IS INTENDED OR SHOULD BE IMPLIED. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kirtley, Susan E., 1972– author. Title: Typical girls : the rhetoric of womanhood in comic strips / Susan E. Kirtley. Other titles: Studies in comics and cartoons. Description: Columbus : The Ohio State University Press, [2021] | Series: Studies in comics and cartoons | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Drawing from the work of Lynn Johnston (For Better or For Worse), Cathy Guisewite (Cathy), Nicole Hollander (Sylvia), Lynda Barry (Ernie Pook’s Comeek), Barbara Brandon-Croft (Where I’m Coming From), Alison Bechdel (Dykes to Watch Out For), and Jan Eliot (Stone Soup), Typical Girls examines the development of womanhood and women’s rights in popular comic strips”—Provided by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2020052823 | ISBN 9780814214572 (cloth) | ISBN 0814214576 (cloth) | ISBN 9780814281222 (ebook) | ISBN 0814281222 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Comic strip characters—Women. | Women in literature. | Women’s rights in literature. | Comic books, strips, etc.—History and criticism. Classification: LCC PN6714 .K47 2021 | DDC 741.5/3522—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052823 COVER DESIGN BY ANGELA MOODY TEXT DESIGN BY JULIET WILLIAMS TYPE SET IN PALATINO For my favorite superhero team—Evelyn, Leone, and Tamasone Castigat ridendo mores. -

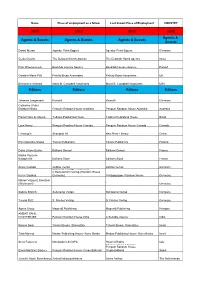

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

2019 Paratcha-Page (PDF, 581Kb)

University of Bristol Department of Historical Studies Best undergraduate dissertations of 2019 Zofia Paratcha-Page An Exploration of Aleister Crowley's Autobiographical Portrayal of His Relationship with Nature The Department of Historical Studies at the University of Bristol is com- mitted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. Our undergraduates are part of that en- deavour. Since 2009, the Department has published the best of the annual disserta- tions produced by our final year undergraduates in recognition of the ex- cellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. An Exploration of Aleister Crowley's Autobiographical Portrayal of His Relationship with Nature 2 Contents Introduction 4 Chapter One: 'Aesthetic Considerations' 11 Chapter Two: 'Mastery' 18 Chapter Three: 'Enchantment' 24 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 34