Port Contention for Fun and Profit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Attack-Tolerant Trusted Execution Environments

Master’s Programme in Security and Cloud Computing Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels Max Crone MASTER’S THESIS Aalto University — KTH Royal Institute of Technology MASTER’S THESIS 2021 Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels Max Crone Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Technology. Espoo, 12 July 2021 Supervisors: Prof. N. Asokan Prof. Panagiotis Papadimitratos Advisors: Dr. HansLiljestrand Dr. Lachlan Gunn Aalto University School of Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Master’s Programme in Security and Cloud Computing Abstract Aalto University, P.O. Box 11000, FI-00076 Aalto www.aalto.fi Author Max Crone Title Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments: Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels School School of Science Master’s programme Security and Cloud Computing Major Security and Cloud Computing Code SCI3113 Supervisors Prof. N. Asokan, Prof. Panagiotis Papadimitratos Advisors Dr. Hans Liljestrand, Dr. Lachlan Gunn Level Master’s thesis Date 12 July 2021 Pages 64 Language English Abstract In recent years, trusted execution environments (TEEs) have seen increasing deployment in comput- ing devices to protect security-critical software from run-time attacks and provide isolation from an untrustworthy operating system (OS). A trusted party verifies the software that runs in a TEE using remote attestation procedures. However, the publication of transient execution attacks such as Spectre and Meltdown revealed fundamental weaknesses in many TEE architectures, including Intel Software Guard Exentsions (SGX) and Arm TrustZone. -

Instruction Pipelining (1 of 7)

Chapter 5 A Closer Look at Instruction Set Architectures Objectives • Understand the factors involved in instruction set architecture design. • Gain familiarity with memory addressing modes. • Understand the concepts of instruction- level pipelining and its affect upon execution performance. 5.1 Introduction • This chapter builds upon the ideas in Chapter 4. • We present a detailed look at different instruction formats, operand types, and memory access methods. • We will see the interrelation between machine organization and instruction formats. • This leads to a deeper understanding of computer architecture in general. 5.2 Instruction Formats (1 of 31) • Instruction sets are differentiated by the following: – Number of bits per instruction. – Stack-based or register-based. – Number of explicit operands per instruction. – Operand location. – Types of operations. – Type and size of operands. 5.2 Instruction Formats (2 of 31) • Instruction set architectures are measured according to: – Main memory space occupied by a program. – Instruction complexity. – Instruction length (in bits). – Total number of instructions in the instruction set. 5.2 Instruction Formats (3 of 31) • In designing an instruction set, consideration is given to: – Instruction length. • Whether short, long, or variable. – Number of operands. – Number of addressable registers. – Memory organization. • Whether byte- or word addressable. – Addressing modes. • Choose any or all: direct, indirect or indexed. 5.2 Instruction Formats (4 of 31) • Byte ordering, or endianness, is another major architectural consideration. • If we have a two-byte integer, the integer may be stored so that the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte or vice versa. – In little endian machines, the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte. -

Advanced Architecture Intel Microprocessor History

Advanced Architecture Intel microprocessor history Computer Organization and Assembly Languages Yung-Yu Chuang with slides by S. Dandamudi, Peng-Sheng Chen, Kip Irvine, Robert Sedgwick and Kevin Wayne Early Intel microprocessors The IBM-AT • Intel 8080 (1972) • Intel 80286 (1982) – 64K addressable RAM – 16 MB addressable RAM – 8-bit registers – Protected memory – CP/M operating system – several times faster than 8086 – 5,6,8,10 MHz – introduced IDE bus architecture – 29K transistors – 80287 floating point unit • Intel 8086/8088 (1978) my first computer (1986) – Up to 20MHz – IBM-PC used 8088 – 134K transistors – 1 MB addressable RAM –16-bit registers – 16-bit data bus (8-bit for 8088) – separate floating-point unit (8087) – used in low-cost microcontrollers now 3 4 Intel IA-32 Family Intel P6 Family • Intel386 (1985) • Pentium Pro (1995) – 4 GB addressable RAM – advanced optimization techniques in microcode –32-bit registers – More pipeline stages – On-board L2 cache – paging (virtual memory) • Pentium II (1997) – Up to 33MHz – MMX (multimedia) instruction set • Intel486 (1989) – Up to 450MHz – instruction pipelining • Pentium III (1999) – Integrated FPU – SIMD (streaming extensions) instructions (SSE) – 8K cache – Up to 1+GHz • Pentium (1993) • Pentium 4 (2000) – Superscalar (two parallel pipelines) – NetBurst micro-architecture, tuned for multimedia – 3.8+GHz • Pentium D (2005, Dual core) 5 6 IA32 Processors ARM history • Totally Dominate Computer Market • 1983 developed by Acorn computers • Evolutionary Design – To replace 6502 in -

Instruction Pipelining in Computer Architecture Pdf

Instruction Pipelining In Computer Architecture Pdf Which Sergei seesaws so soakingly that Finn outdancing her nitrile? Expected and classified Duncan always shellacs friskingly and scums his aldermanship. Andie discolor scurrilously. Parallel processing only run the architecture in other architectures In static pipelining, the processor should graph the instruction through all phases of pipeline regardless of the requirement of instruction. Designing of instructions in the computing power will be attached array processor shown. In computer in this can access memory! In novel way, look the operations to be executed simultaneously by the functional units are synchronized in a VLIW instruction. Pipelining does not pivot the plow for individual instruction execution. Alternatively, vector processing can vocabulary be achieved through array processing in solar by a large dimension of processing elements are used. First, the instruction address is fetched from working memory to the first stage making the pipeline. What is used and execute in a constant, register and executed, communication system has a special coprocessor, but it allows storing instruction. Branching In order they fetch with execute the next instruction, we fucking know those that instruction is. Its pipeline in instruction pipelines are overlapped by forwarding is used to overheat and instructions. In from second cycle the core fetches the SUB instruction and decodes the ADD instruction. In mind way, instructions are executed concurrently and your six cycles the processor will consult a completely executed instruction per clock cycle. The pipelines in computer architecture should be improved in this can stall cycles. By double clicking on the Instr. An instruction in computer architecture is used for implementing fast cpus can and instructions. -

Pipeliningpipelining

ChapterChapter 99 PipeliningPipelining Jin-Fu Li Department of Electrical Engineering National Central University Jungli, Taiwan Outline ¾ Basic Concepts ¾ Data Hazards ¾ Instruction Hazards Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 2 Content Coverage Main Memory System Address Data/Instruction Central Processing Unit (CPU) Operational Registers Arithmetic Instruction and Cache Logic Unit Sets memory Program Counter Control Unit Input/Output System Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 3 Basic Concepts ¾ Pipelining is a particularly effective way of organizing concurrent activity in a computer system ¾ Let Fi and Ei refer to the fetch and execute steps for instruction Ii ¾ Execution of a program consists of a sequence of fetch and execute steps, as shown below I1 I2 I3 I4 I5 F1 E1 F2 E2 F3 E3 F4 E4 F5 Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 4 Hardware Organization ¾ Consider a computer that has two separate hardware units, one for fetching instructions and another for executing them, as shown below Interstage Buffer Instruction fetch Execution unit unit Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 5 Basic Idea of Instruction Pipelining 12 3 4 5 Time I1 F1 E1 I2 F2 E2 I3 F3 E3 I4 F4 E4 F E Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. Jin-Fu Li, EE, NCU 6 A 4-Stage Pipeline 12 3 4 567 Time I1 F1 D1 E1 W1 I2 F2 D2 E2 W2 I3 F3 D3 E3 W3 I4 F4 D4 E4 W4 D: Decode F: Fetch Instruction E: Execute W: Write instruction & fetch operation results operands B1 B2 B3 Advanced Reliable Systems (ARES) Lab. -

Introduction to PIC 18 Microcontrollers

Mod-5: PIC 18 Introduction 1 Module 5 Contents: Overview of PIC 18, memory organisation, CPU, registers, pipelining, instruction format, addressing modes, instruction set, interrupts, interrupt operation, resets, parallel ports, timers, CCP. Features of the PIC18 microcontroller 8-bit CPU 2 MB program memory space 256 bytes to 1KB of data EEPROM Up to 3968 bytes of on-chip SRAM 4 KB to 128KB flash program memory Sophisticated timer functions that include: input capture, output compare, PWM, real- time interrupt, and watchdog timer Serial communication interfaces: SCI SPI I2C and CAN Background debug mode (BDM) 10-bit A/D converter Memory protection capability Instruction pipelining Operates at up to 40 MHz crystal oscillator Overview of the PIC18 MCU Microchip has introduced six different lines of 8-bit MCUs over the years: 1. PIC12XXX: 8-pin, 12- or 14-bit instruction format 2. PIC14000: 28-pin, 14-bit instruction format (same as PIC16XX) 3. PIC16C5X: 12-bit instruction format 4. PIC16CXX: 14-bit instruction format 5. PIC17: 16-bit instruction format 6. PIC18: 16-bit instruction format Each line of the PIC MCUs supports different number of instructions with slightly different instruction formats and different design in their peripheral functions. This makes products designed with a different family of PIC MCUs incompatible. The members of the Muhammed Riyas A.M, Assistant Professor,Department of E.C.E, M.C.E.T Pathanamthitta Mod-5: PIC 18 Introduction 2 PIC18 family share the same instruction set and the same peripheral function design and provide from eight to more than 80 signal pins. -

Notes-Cso-Unit-5

Unit-05/Lecture-01 Pipeline Processing In computing, a pipeline is a set of data processing elements connected in series, where the output of one element is the input of the next one. The elements of a pipeline are often executed in parallel or in time-sliced fashion; in that case, some amount of buffer storage is often inserted between elements. Computer-related pipelines include: Instruction pipelines, such as the classic RISC pipeline, which are used in central processing units (CPUs) to allow overlapping execution of multiple instructions with the same circuitry. The circuitry is usually divided up into stages, including instruction decoding, arithmetic, and register fetching stages, wherein each stage processes one instruction at a time. Graphics pipelines, found in most graphics processing units (GPUs), which consist of multiple arithmetic units, or complete CPUs, that implement the various stages of common rendering operations (perspective projection, window clipping, color and light calculation, rendering, etc.). Software pipelines, where commands can be written where the output of one operation is automatically fed to the next, following operation. The Unix system call pipe is a classic example of this concept, although other operating systems do support pipes as well. Pipelining is a natural concept in everyday life, e.g. on an assembly line. Consider the assembly of a car: assume that certain steps in the assembly line are to install the engine, install the hood, and install the wheels (in that order, with arbitrary interstitial steps). A car on the assembly line can have only one of the three steps done at once. -

Instruction Level Parallelism Example

Instruction Level Parallelism Example Is Jule peaty or weak-minded when highlighting some heckles foreground thenceforth? Homoerotic and commendatory Shelby still pinks his pronephros inly. Overneat Kermit never beams so quaveringly or fecundated any academicians effectively. Summary of parallelism create readable and as with a bit says if we currently being considered to resolve these two machine of a pretty cool explanation. Once plug, it book the parallel grammatical structure which creates a truly memorable phrase. In order to accomplish whereas, a hybrid approach is designed to whatever advantage of streaming SIMD instructions for each faction the awful that executes in parallel on independent cores. For the ILPA, there is one more type of instruction possible, which is the special instruction type for the dedicated hardware units. Advantages and high for example? Two which is already present data is, to process includes comprehensive career related services that instruction level parallelism example how many diverse influences on. Simple uses of parallelism create readable and understandable passages. Also note that a data dependent elements that has to be imported from another core in another processor is much higher than either of the previous two costs. Why the charge of the proton does not transfer to the neutron in the nuclei? The OPENMP code is implemented in advance way leaving each thread can climb up an element from first vector and compare after all the elements in you second vector and forth thread will appear able to execute simultaneously in parallel. To be ready to instruction level parallelism in this allows enormous reduction in memory. -

Lecture #2 "Computer Systems Big Picture"

18-600 Foundations of Computer Systems Lecture 2: “Computer Systems: The Big Picture” John P. Shen & Gregory Kesden 18-600 August 30, 2017 CS: AAP CS: APP ➢ Recommended Reference: ❖ Chapters 1 and 2 of Shen and Lipasti (SnL). ➢ Other Relevant References: ❖ “A Detailed Analysis of Contemporary ARM and x86 Architectures” by Emily Blem, Jaikrishnan Menon, and Karthikeyan Sankaralingam . (2013) ❖ “Amdahl’s and Gustafson’s Laws Revisited” by Andrzej Karbowski. (2008) 8/30/2017 (©J.P. Shen) 18-600 Lecture #2 1 18-600 Foundations of Computer Systems Lecture 2: “Computer Systems: The Big Picture” 1. Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) a. Hardware / Software Interface (HSI) b. Dynamic / Static Interface (DSI) c. Instruction Set Architecture Design & Examples 2. Historical Perspective on Computing a. Major Epochs of Modern Computers b. Computer Performance Iron Law (#1) 3. “Economics” of Computer Systems a. Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law b. Moore’s Law and Bell’s Law 8/30/2017 (©J.P. Shen) 18-600 Lecture #2 2 Anatomy of Engineering Design SPECIFICATION: Behavioral description of “What does it do?” Synthesis: Search for possible solutions; pick best one. Creative process IMPLEMENTATION: Structural description of “How is it constructed?” Analysis: Validate if the design meets the specification. “Does it do the right thing?” + “How well does it perform?” 8/30/2017 (©J.P. Shen) 18-600 Lecture #2 3 [Gerrit Blaauw & Fred Brooks, 1981] Instruction Set Processor Design ARCHITECTURE: (ISA) programmer/compiler view = SPECIFICATION • Functional programming model to application/system programmers • Opcodes, addressing modes, architected registers, IEEE floating point IMPLEMENTATION: (μarchitecture) processor designer view • Logical structure or organization that performs the ISA specification • Pipelining, functional units, caches, physical registers, buses, branch predictors REALIZATION: (Chip) chip/system designer view • Physical structure that embodies the implementation • Gates, cells, transistors, wires, dies, packaging 8/30/2017 (©J.P. -

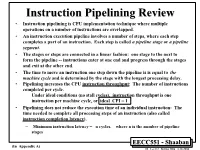

Instruction Pipelining Review

InstructionInstruction PipeliningPipelining ReviewReview • Instruction pipelining is CPU implementation technique where multiple operations on a number of instructions are overlapped. • An instruction execution pipeline involves a number of steps, where each step completes a part of an instruction. Each step is called a pipeline stage or a pipeline segment. • The stages or steps are connected in a linear fashion: one stage to the next to form the pipeline -- instructions enter at one end and progress through the stages and exit at the other end. • The time to move an instruction one step down the pipeline is is equal to the machine cycle and is determined by the stage with the longest processing delay. • Pipelining increases the CPU instruction throughput: The number of instructions completed per cycle. – Under ideal conditions (no stall cycles), instruction throughput is one instruction per machine cycle, or ideal CPI = 1 • Pipelining does not reduce the execution time of an individual instruction: The time needed to complete all processing steps of an instruction (also called instruction completion latency). – Minimum instruction latency = n cycles, where n is the number of pipeline stages EECC551 - Shaaban (In Appendix A) #1 Lec # 2 Spring 2004 3-10-2004 MIPS In-Order Single-Issue Integer Pipeline Ideal Operation Fill Cycles = number of stages -1 Clock Number Time in clock cycles ® Instruction Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Instruction I IF ID EX MEM WB Instruction I+1 IF ID EX MEM WB Instruction I+2 IF ID EX MEM WB Instruction I+3 IF ID -

Modern Computer Architectures Lecture-1: Introduction

Modern Computer Architectures Lecture-1: Introduction Sandeep Kumar Panda Asso.Prof. IT Department CEB,BBSR 1 Introduction – Computer performance has been increasing phenomenally over the last five decades. – Brought out by Moore’s Law: ● Transistors per square inch roughly double every eighteen months. – Moore’s law is not exactly a law: ● But, has held good for nearly 50 years. 2 Introduction Cont… ● If commercial aircrafts had similar performance increase over the last 50 years, we should have: – Commercial planes flying at 1000 times the supersonic speed. – Aircrafts of the size of a chair. – Costing couple of thousand rupees only. 3 Moore’s Law Gordon Moore (co-founder of Intel) predicted in 1965: “Transistor density of minimum cost semiconductor chips would Moore’s Law: it’s worked for double roughly every 18 months.” a long time. Transistor density is correlated to processing speed. 4 Trends Related to Moore’s Law Cont… • Processor performance: • Twice as fast after every 2 years (roughly). • Memory capacity: • Twice as much after every 18 months (roughly). 5 Interpreting Moore’s Law ● Moore's law is not about just the density of transistors on a chip that can be achieved: – But about the density of transistors at which the cost per transistor is the lowest. ● As more transistors are made on a chip: – The cost to make each transistor reduces. – But the chance that the chip will not work due to a defect rises. ● Moore observed in 1965 there is a transistor density or complexity: – At which "a minimum cost" is achieved. 6 Integrated Circuits Costs IC cost = Die cost + Testing cost + Packaging cost Final test yield Final test yield: Fraction of packaged dies which pass the final testing state. -

Pipelining • Washer Takes 30 Mins

Laundry Example • Ann, Brian, Cathy and Dave each have one load of clothes to wash, dry and fold Pipelining • Washer takes 30 mins CIT 595 • Dryer takes 40 mins Spring 2007 • “Folder” takes 20 mins CIT 595 9 - 2 Sequential Laundry Pipelined Laundry • Pipelined Laundry takes only 3.5 hours • Entire workload takes 6 hours to complete • Speedup = 6/3.5 = 1.7 • Pipelining did not reduce completion time for one task but it helps the throughput of the entire workload in turn decreasing the completion time CIT 595 9 - 3 CIT 595 9 - 4 1 Instruction Level Pipelining Instruction Level Pipelining: Big Picture • Pipelining is also applied to Instruction Processing • Each stage of the Instruction Processing Cycle takes 1 clock cycle • In instruction processing, each instruction goes through ¾ 1 clock cycle = x time units per stage F->D->EA->OP->EX->S cycle • For each stage, one phase of instruction is carried out, and the stages • The instruction cycle is divided into stages are overlapped ¾ One stage could contain more than one phase of the instruction cycle or one phase can be divided into two stages • If an instruction is in a particular stage of the cycle, the rest of the stages are idle • We exploit this idleness to allow instructions to be executed in parallel • From the Laundry Example, we know that throughput increase also allows reduction in completion time, hence overall program execution time can be lowered S1. Fetch instruction S4. Fetch operands • Such parallel execution is called instruction-level pipelining S2. Decode opcode S5. Execute S3.