Clara Kimball Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier De Presse ECLAIR

ECLAIR 1907 - 2007 du 6 au 25 juin 2007 Créés en 1907, les Studios Eclair ont constitué une des plus importantes compagnies de production du cinéma français des années 10. Des serials trépidants, des courts-métrages burlesques, d’étonnants films scientifiques y furent réalisés. Le développement de la société Eclair et le succès de leurs productions furent tels qu’ils implantèrent des filiales dans le monde, notamment aux Etats-Unis. Devenu une des principales industries techniques du cinéma français, Eclair reste un studio prisé pour le tournage de nombreux films. La rétrospective permettra de découvrir ou de redécouvrir tout un moment essentiel du cinéma français. En partenariat avec et Remerciements Les Archives Françaises du Film du CNC, Filmoteca Espa ňola, MoMA, National Film and Television Archive/BFI, Nederlands Filmmuseum, Library of Congress, La Cineteca del Friuli, Lobster films, Marc Sandberg, Les Films de la Pléiade, René Chateau, StudioCanal, Tamasa, TF1 International, Pathé. SOMMAIRE « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » p2-4 « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Autour des films : p5-6 SEANCE « LES FILMS D’A.-F. PARNALAND » Jeudi 7 juin 19h30 salle GF JOURNEE D’ETUDES ECLAIR Jeudi 14 juin, Entrée libre Programmation Eclair p7-18 Renseignements pratiques p19 La Kermesse héroïque de Jacques Feyder (1935) / Coll. CF, DR Contact presse Cinémathèque française Elodie Dufour - Tél. : 01 71 19 33 65 - [email protected] « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Eclair, c’est l’histoire d’une remarquable ténacité industrielle innovante au service des films et de leurs auteurs, grâce à une double activité de studio et de laboratoire, s’enrichissant mutuellement depuis un siècle. -

Fort Lee Booklet

New Jersey and the Early Motion Picture Industry by Richard Koszarski, Fort Lee Film Commission The American motion picture industry was born and raised in New Jersey. Within a generation this powerful new medium passed from the laboratories of Thomas Edison to the one-reel masterworks of D.W. Griffith to the high-tech studio town of Fort Lee with rows of corporate film factories scattered along the local trolley lines. Although a new factory town was eventually established on the West Coast, most of the American cinema’s real pioneers first paid their dues on the stages (and streets) of New Jersey. On February 25, 1888, the Photographer Eadweard Muybridge lectured on the art of motion photography at New Jersey’s Orange Music Hall. He demonstrated his Zoopraxiscope, a simple projector designed to reanimate the high-speed still photographs of human and animal subjects that had occupied him for over a decade. Two days later he visited Thomas Alva Edison at his laboratory in West Orange, and the two men discussed the possibilities of linking the Zoopraxiscope with Edison’s phonograph. Edison decided to proceed on his own and assigned direction of the project to his staff photographer, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. In 1891 Dickson became the first man to record sequential photographic images on a strip of transparent celluloid film. Two years later, in anticipation of commercialization of the new process, he designed and built the first photographic studio intended for the production of motion pictures, essentially a tar paper shack mounted on a revolving turntable (to allow his subjects to face the direct light of the sun). -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams The following is a list of films directly related to my research for this book. There is a more extensive list for Lucile in Randy Bryan Bigham, Lucile: Her Life by Design (San Francisco and Dallas: MacEvie Press Group, 2012). Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon The American Princess (Kalem, 1913, dir. Marshall Neilan) Our Mutual Girl (Mutual, 1914) serial, visit to Lucile’s dress shop in two episodes The Perils of Pauline (Pathé, 1914, dir. Louis Gasnier), serial The Theft of the Crown Jewels (Kalem, 1914) The High Road (Rolfe Photoplays, 1915, dir. John Noble) The Spendthrift (George Kleine, 1915, dir. Walter Edwin), one scene shot in Lucile’s dress shop and her models Hebe White, Phyllis, and Dolores all appear Gloria’s Romance (George Klein, 1916, dir. Colin Campbell), serial The Misleading Lady (Essanay Film Mfg. Corp., 1916, dir. Arthur Berthelet) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Film Corp., 1917, dir. Marshall Neilan) The Rise of Susan (World Film Corp., 1916, dir. S.E.V. Taylor), serial The Strange Case of Mary Page (Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, 1916, dir. J. Charles Haydon), serial The Whirl of Life (Cort Film Corporation, 1915, dir. Oliver D. Bailey) Martha’s Vindication (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916, dir. Chester M. Franklin, Sydney Franklin) The High Cost of Living (J.R. Bray Studios, 1916, dir. Ashley Miller) Patria (International Film Service Company, 1916–17, dir. Jacques Jaccard), dressed Irene Castle The Little American (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. Cecil B. DeMille) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Fin-De-Siècle Bohemian's Self-Division by John Brad Macdonald Department of English Mcgill Univers

Ambivalent Ambitions: The fin-de-siècle Bohemian’s Self-Division By John Brad MacDonald Department of English McGill University, Montreal December, 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Brad MacDonald 2016 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................v Résumé .......................................................................................................................................... vi Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 I. The Rise of the Parisian Mecca: The Beginning of French Bohemia ............................14 II. From The Left Bank to Soho: The Early Days of English Bohemia ............................22 III. Rossetti, Whistler, and Wilde: The Rise of English Bohemianism .............................27 IV. Tales from the Margins: The Bohemian Text ..............................................................47 Chapter One: “Original work is never dans le movement”: The Bohemian Collective in George Moore’s A Modern Lover ...............................................................................................................59 Chapter Two: “A Place for -

The Picture Show Annual (1928)

Hid •v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/pictureshowannuaOOamal Corinne Griffith, " The Lady in Ermine," proves a shawl and a fan are just as becoming. Corinne is one of the long-established stars whose popularity shows no signs of declining and beauty no signs of fading. - Picture Show Annual 9 rkey Ktpt~ thcMouies Francis X. Bushman as Messala, the villain of the piece, and Ramon Novarro, the hero, in " Ben Hut." PICTURESQUE PERSONALITIES OF THE PICTURES—PAST AND PRESENT ALTHOUGH the cinema as we know it now—and by that I mean plays made by moving pictures—is only about eighteen years old (for it was in the Wallace spring of 1908 that D. W. Griffith started to direct for Reid, the old Biograph), its short history is packed with whose death romance and tragedy. robbed the screen ofa boyish charm Picture plays there had been before Griffith came on and breezy cheer the scene. The first movie that could really be called iness that have a picture play was " The Soldier's Courtship," made by never been replaced. an Englishman, Robert W. Paul, on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre in 18% ; but it was in the Biograph Studio that the real start was made with the film play. Here Mary Pickford started her screen career, to be followed later by Lillian and Dorothy Gish, and the three Talmadge sisters. Natalie Talmadge did not take as kindly to film acting as did her sisters, and when Norma and Constance had made a name and the family had gone from New York to Hollywood Natalie went into the business side of the films and held some big positions before she retired on her marriage with Buster Keaton. -

Harpercollins Canada Fall 2010

harpercollins canada fall 2010 HarperCollinsCanada is a proud sponsor of www.harpercollins.ca SALES, MARKETING, PUBLICITY & EDITORIAL 2 Bloor Street East, 20th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 1A8 • Phone: 416.975.9334 • Fax: 416.975.9884 DISTRIBUTION CENTRE 1995 Markham Road, Scarborough, Ontario, M1B 5M8 • Phone: 416.321.2241 • Toll-Free Phone: 1.800.387.0117 • Fax: 416.321.3033 • Toll-Free Fax: 1.800.668.5788 CATALOGUE ISBN: 9780999937204 For your viewing pleasure . a select number of our catalogues are now available online. These electronic catalogues are virtual replicas of our traditional ones, with the Sell what you love added benefit of being on your screen and available to you 24/7. In addition to all the great catalogue material at your fingertips, the online versions include our rich multimedia files (with trailers and author videos), as well as links to any other relevant web materials. And let’s not forget the added value of going green. The In a world where we’re constantly figuring out how to give back to the earth, HarperCollins www.HarperCollinsCatalogues.ca is another way to make a difference. Canada Hand-selling Award Fiction or non-fiction, biography or self-help, debut novel or seasoned classic—expose readers to talent on the page. The top hand-seller will receive $500 and the bookstore will receive $1000 in co-op. Quantity of sales is not the only determining factor— we want to know your hand-selling story. To find out more, visitwww.harpercollins.ca/handsellingaward Managers can email submissions to [email protected] Contents page 2 New Fiction and Non-fiction page 33 Cookbooks page 35 Harper Paperbacks page 57 Children’s Books pages 70-71 Index page 72 Key Contacts Please note: Prices, dates and specifications listed in this catalogue are subject to change without notice. -

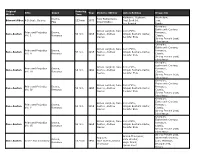

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen, -

Camera (1920-1922)

7 l Page To>o "The Digest of the Motion Picture Industry” CAM ERA A Liberal Privilege of Conversion Besides the safety of enormous assets and large and increasing earnings, besides a substantial and profitable yield, there is a very liberal privilege of conversion in the $3 , 000,000 Carnation Milk Products Company Five-Year Sinking Fund 7 % Convertible Gold Notes notes convertible at option after November I creased in past five years. These are , over 400% 1921, and until ten days prior to maturity or redemption into Total assets after deducting all indebtedness, except this note, 7% Cumulative Sinking Fund Preferred Stock on the basis of amount to more than four times principal of this issue. I 00 for these notes and 95 for the stock. With these notes Net earnings for past ten years have averaged more than four at 96J/2 this is equivalent to buying the stock at 91 /i- and one-half times interest charges, and during the past five Thus you see that at your option you have either a long- years more than seven times. term, high yielding preferred stock or a short-term, high- There is no other bonded or funded indebtedness and at yielding note. Preferred stock is subject to call at 1 1 0 and present no outstanding preferred stock. accrued dividends, and the usual features of safety. You will want to invest your savings and surplus funds in This Company is one of the largest and most successful of its this decidedly good investment. Call, write or phone for kind in America. -

William A. Brady: Theatre Entrepreneur

WILLIAM A. BRADY: THEATRE ENTREPRENEUR By NEVIS EZELLE HAGLER, JR, A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1975 *J^-J UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 5185 3 1262 08552 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express rny appreciation to the research staff and director of the Theatre Collection at the Lincoln Center Library of the Performing Arts and to Mr. Louis Rachow, of the Players Club, for their valuable assistance and guidance. Special appreciation is extended to two of the theatre's most gracious actresses, Miss Helen Kayes and Miss Madge Kennedy, for their recollec- tions, assistance, and time. My gratitude is also ex- tended to Dr. Richard L. Green, Dr. Clyde G. Sumpter, Dr. Sidney Homan, and Dr. Norman Markel, for their aid in reading the study and offering valuable criticism, A special note of appreciation is due Dr. L. L. Zimmerman, the chairman of this work, for his encourage- ment, criticism, and, most importantly, for his friendship, PREFACE During his lifetime, William A. Brady was one of the most active and successful producers in the American theatre. Since his death, in 1950, his reputation has faded into relative obscurity. No study of his career has been made, and he is mentioned only briefly and with- out regularity in works dealing with the American theatre of the first half of the twentieth century. This study will examine his life and career as a theatrical producer in order to demonstrate the ways in which Brady's career exemplified certain aspects of the early twentieth century American theatre.