Special M: the Evolution of the Recreational Use of Ketamine and Methoxetamine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals

Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals Virbac (Australia) Pty Limited Chemwatch Hazard Alert Code: 1 Chemwatch: 6978267 Issue Date: 11/01/2019 Version No: 4.1.16.10 Print Date: 08/31/2021 Safety Data Sheet according to WHS Regulations (Hazardous Chemicals) Amendment 2020 and ADG requirements L.GHS.AUS.EN SECTION 1 Identification of the substance / mixture and of the company / undertaking Product Identifier Product name Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals Chemical Name Not Applicable Synonyms APVMA No.: 38837 Chemical formula Not Applicable Other means of identification Not Available Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Relevant identified uses For the anaesthesia and immobilisation of dogs, cats, zoo and wild animals. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Registered company name Virbac (Australia) Pty Limited Address 361 Horsley Road Milperra NSW 2214 Australia Telephone 1800 242 100 Fax +61 2 9772 9773 Website au.virbac.com Email [email protected] Emergency telephone number Association / Organisation Poisons Information Centre Emergency telephone 13 11 26 numbers Other emergency telephone Not Available numbers SECTION 2 Hazards identification Classification of the substance or mixture NON-HAZARDOUS CHEMICAL. NON-DANGEROUS GOODS. According to the WHS Regulations and the ADG Code. ChemWatch Hazard Ratings Min Max Flammability 1 Toxicity 1 0 = Minimum Body Contact 1 1 = Low 2 = Moderate Reactivity 1 3 = High Chronic 0 4 = Extreme Poisons Schedule S4 Classification [1] Not Applicable Label elements Hazard pictogram(s) Not Applicable Signal word Not Applicable Hazard statement(s) Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Prevention Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Response Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Storage Page 1 continued.. -

Medical Review Officer Manual

Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Medical Review Officer Manual for Federal Agency Workplace Drug Testing Programs EFFECTIVE OCTOBER 1, 2010 Note: This manual applies to Federal agency drug testing programs that come under Executive Order 12564 dated September 15, 1986, section 503 of Public Law 100-71, 5 U.S.C. section 7301 note dated July 11, 1987, and the Department of Health and Human Services Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs (73 FR 71858) dated November 25, 2008 (effective October 1, 2010). This manual does not apply to specimens submitted for testing under U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Procedures for Transportation Workplace Drug and Alcohol Testing Programs (49 CFR Part 40). The current version of this manual and other information including MRO Case Studies are available on the Drug Testing page under Medical Review Officer (MRO) Resources on the SAMHSA website: http://www.workplace.samhsa.gov Previous Versions of this Manual are Obsolete 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1. The Medical Review Officer (MRO)........................................................................... 6 Chapter 2. The Federal Drug Testing Custody and Control Form ................................................ 7 Chapter 3. Urine Drug Testing ...................................................................................................... 9 A. Federal Workplace Drug Testing Overview.................................................................. -

3. 4 Ketamina E Analoghi

NEW DRUGS Nuove Sostanze Psicoattive 3. 4 Ketamina e analoghi 765 766 NEW DRUGS Nuove Sostanze Psicoattive Ketamina Nome Ketamina; (Ketamine) Struttura molecolare O NH CH3 Cl Formula di struttura C13H16ClNO Numero CAS 6740-88-1 (base libera) / 1867-66-9 (sale cloridrato) Nome IUPAC 2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-(methylamino)cyclohexan-1-one Altri nomi (±)-2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-methylamino)cyclohexanone; (±)-2-(o-chlorophenyl)-2-methylamino)cyclo hexanone; 2-(methylami- no)-2-(2-chlorophenyl)cyclohexanone; 2-(methylamino)-2-(o-chlorophenyl) cyclohexanone; (±)-Ketamine; CI-581; CL-369; CN- 52,372-2. Nomi commerciali (per uso umano o veterinario): Esketamie; Ketalar base; Ketamine Base; Ketavet; Ketolar; Vetalar Ketalar, Ketamine Panpharma, Ketanest-S; Ketalar, Ketaminol; Vetalar Vet., Ketaminol Vet.; Clorketam, Imalgene, Anesketin, Ketamine Ceva, Narketan, Ketaset, Anesketin. Nomi gergali: K, special K, kit kat, tac et tic, cat valium, vitamin K, ket, super K, Kaddy, Kate, Ket, Kéta K, Jet, Super acid, 1980 acid, Special LA coke, Super C, Purple, Mauve, Green. Peso molecolare 237.725 g/mol Aspetto Polvere/cristalli bianchi. Punto di fusione della ketamina base libera: 92-93 °C; del cloridrato: 262-263°C. Informazioni generali La ketamina è una arilcicloalchilamina strutturalmente correlata alle ciclidine quali ad esempio l’etilciclidina, la fenciclidina, la roliciclidina e la tenociclidina. La ketamina è una molecola di origine sintetica, sintetizzata nel 1962, brevettata in Belgio nel 1963. E’ stata progettata nell’ambito della ricerca di analoghi strutturali delle cicloesilamine a cui appartiene anche la fenciclidina (PCP). La ketamina ha proprietà anestetiche ed analgesiche. E’ ampiamente utilizzata in ambito veterinario, molto meno come anestetico nell’uomo. -

Patient Risks & Preparation for a Successful Sedation Or Anesthetic Event

Patient risks & Sleep preparation for a successful well… sedation or anesthetic event Odette O, DVM, DACVAA ▪ Sedation versus general anesthetic: what are the considerations? ▪ What are the risks (literally) of sedation &/or anesthesia? ▪ Optimize patient preparation prior to sedation/anesthesia whenever possible! ▪ Be prepared: Who? What? Where? When? Why? ▪ Troubleshooting a rough recovery… ▪ ↑ risk of mortality seen with increasing ASA status ▪ Importance of patient evaluation and stabilization PRIOR to commencement of procedure ▪ Identify risk factors and monitor carefully ▪ Largest proportion of deaths in post-procedure period ▪ Continued patient monitoring & support vital • Diagnostic Imaging • Radiographs, CT, U/S • Biopsies • Small wound repair • Bandaging • Convenience • Faster recovery times • Reversible options • ↓ $ • ↑ margin of safety ▪ Reversible unconsciousness ▪ Amnesia ▪ Analgesia ▪ Muscle relaxation ▪ Perform a procedure ▪ w/o suffering ▪ Safety ▪ Patient ▪ Veterinary Care Provider(s) ▪ Multi-modal approach ▪ DO NOT “mask down” (canine/feline) patients! ▪ Patient & occupational safety concerns ▪ MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) = amount of inhalant needed for 50% of patients non- responsive to supramaximal stimulus ▪ Isoflurane: ≈ 1.3% canine, ≈1.6% feline ▪ Sevoflurane: ≈ 2.3% canine, ≈ 3% feline ▪ allows estimate of amount inhalant required ▪ factors: procedure, patient pre-med response, inhalant ▪ Minimal calculations needed ▪ Inhalant effective in every species we encounter ▪ Predictable effects on most patients, -

Interplay Between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

brain sciences Review Interplay between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Matthew B. Phillips 1,2, Aparna Nigam 1 and Jon W. Johnson 1,2,* 1 Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA; [email protected] (M.B.P.); [email protected] (A.N.) 2 Center for Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(412)-624-4295 Received: 27 October 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Drugs that inhibit ion channel function by binding in the channel and preventing current flow, known as channel blockers, can be used as powerful tools for analysis of channel properties. Channel blockers are used to probe both the sophisticated structure and basic biophysical properties of ion channels. Gating, the mechanism that controls the opening and closing of ion channels, can be profoundly influenced by channel blocking drugs. Channel block and gating are reciprocally connected; gating controls access of channel blockers to their binding sites, and channel-blocking drugs can have profound and diverse effects on the rates of gating transitions and on the stability of channel open and closed states. This review synthesizes knowledge of the inherent intertwining of block and gating of excitatory ligand-gated ion channels, with a focus on the utility of channel blockers as analytic probes of ionotropic glutamate receptor channel function. Keywords: ligand-gated ion channel; channel block; channel gating; nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; ionotropic glutamate receptor; AMPA receptor; kainate receptor; NMDA receptor 1. Introduction Neuronal information processing depends on the distribution and properties of the ion channels found in neuronal membranes. -

From NMDA Receptor Hypofunction to the Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia J

REVIEW The Neuropsychopharmacology of Phencyclidine: From NMDA Receptor Hypofunction to the Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia J. David Jentsch, Ph.D., and Robert H. Roth, Ph.D. Administration of noncompetitive NMDA/glutamate effects of these drugs are discussed, especially with regard to receptor antagonists, such as phencyclidine (PCP) and differing profiles following single-dose and long-term ketamine, to humans induces a broad range of exposure. The neurochemical effects of NMDA receptor schizophrenic-like symptomatology, findings that have antagonist administration are argued to support a contributed to a hypoglutamatergic hypothesis of neurobiological hypothesis of schizophrenia, which includes schizophrenia. Moreover, a history of experimental pathophysiology within several neurotransmitter systems, investigations of the effects of these drugs in animals manifested in behavioral pathology. Future directions for suggests that NMDA receptor antagonists may model some the application of NMDA receptor antagonist models of behavioral symptoms of schizophrenia in nonhuman schizophrenia to preclinical and pathophysiological research subjects. In this review, the usefulness of PCP are offered. [Neuropsychopharmacology 20:201–225, administration as a potential animal model of schizophrenia 1999] © 1999 American College of is considered. To support the contention that NMDA Neuropsychopharmacology. Published by Elsevier receptor antagonist administration represents a viable Science Inc. model of schizophrenia, the behavioral and neurobiological KEY WORDS: Ketamine; Phencyclidine; Psychotomimetic; widely from the administration of purportedly psychot- Memory; Catecholamine; Schizophrenia; Prefrontal cortex; omimetic drugs (Snyder 1988; Javitt and Zukin 1991; Cognition; Dopamine; Glutamate Jentsch et al. 1998a), to perinatal insults (Lipska et al. Biological psychiatric research has seen the develop- 1993; El-Khodor and Boksa 1997; Moore and Grace ment of many putative animal models of schizophrenia. -

Moves to Amend HF No. 2711 As Follows

05/05/20 REVISOR KLL/JK A20-0767 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 2711 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the column under "APPROPRIATIONS" are added to or reduce the 1.7 appropriations in Laws 2019, First Special Session chapter 5, to the agencies and for the 1.8 purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, or another 1.9 named fund, and are available for the fiscal year indicated for each purpose. 1.10 APPROPRIATIONS 1.11 Available for the Year 1.12 Ending June 30 1.13 2020 2021 1.14 Sec. 2. CORRECTIONS 1.15 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 205,000 $ 5,545,000 1.16 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.17 purpose are specified in the following 1.18 subdivisions. 1.19 Subd. 2. Correctional Institutions -0- (2,545,000) 1.20 To account for overall bed impact savings of 1.21 reductions in the penalties for controlled 1.22 substances offenses involving the possession 1.23 of marijuana, investments in community 1.24 supervision, and increased penalties for sex 1.25 trafficking offenses, the fiscal year 2021 Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 05/05/20 REVISOR KLL/JK A20-0767 2.1 appropriation from Laws 2019, First Special 2.2 Session chapter 5, article 1, section 15, 2.3 subdivision 2, is reduced by $2,545,000. 2.4 Subd. -

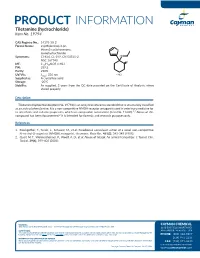

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION Tiletamine (hydrochloride) Item No. 19794 CAS Registry No.: 14176-50-2 Formal Name: 2-(ethylamino)-2-(2- thienyl)-cyclohexanone, S monohydrochloride Synonyms: CI-634, CL-399, CN 54521-2, HN NSC 167740 O MF: C12H17NOS • HCl FW: 259.8 Purity: ≥98% • HCl UV/Vis.: λmax: 236 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C Stability: As supplied, 2 years from the QC date provided on the Certificate of Analysis, when stored properly Description Tiletamine (hydrochloride) (Item No. 19794) is an analytical reference standard that is structurally classified as an arylcyclohexylamine. It is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist used in veterinary medicine for its anesthetic and sedative properties, which are comparable to ketamine (Item No. 11630).1,2 Abuse of this compound has been documented.2 It is intended for forensic and research purposes only. References 1. Klockgether, T., Turski, L., Schwarz, M., et al. Paradoxical convulsant action of a novel non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, tiletamine. Brain Res. 461(2), 343-348 (1988). 2. Quail, M. T., Weimersheimer, P., Woolf, A. D., et al. Abuse of telazol: An animal tranquilizer. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 39(4), 399-402 (2001). WARNING CAYMAN CHEMICAL THIS PRODUCT IS FOR RESEARCH ONLY - NOT FOR HUMAN OR VETERINARY DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. 1180 EAST ELLSWORTH RD SAFETY DATA ANN ARBOR, MI 48108 · USA This material should be considered hazardous until further information becomes available. Do not ingest, inhale, get in eyes, on skin, or on clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Before use, the user must review the complete Safety Data Sheet, which has been sent via email to your institution. -

Presence of Methoxetamine in Drug Samples Delivered As Ketamine for Substance Analysis

Is this really ketamine? Presence of methoxetamine in drug samples delivered as ketamine for substance analysis P. Quintana2, Á. Palma1,5, M. Grifell1,2, J. Tirado3,5, C. Gil2, M. Ventura2, I. Fornís3, S. López2, V. Perez1,5, M. Torrens1,3,5, M. Farré3,4,5, L. Galindo1,3,5 1Institut de Neuropsiquiatria i Addiccions, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain 2Asocicación Bienestar y Desarrollo, Energy Control, Barcelona, Spain 3IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute), Barcelona, Spain 4Hospital Germans Trías i Pujol, Servei de Farmacología Clínica, Barcelona, Spain 5Departament de Psiquiatria, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Introduction New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs that have recently become available, and are not world-wide regulated. They often intend to mimic the effect of controlled drugs (1), becoming a public health concern. In 2014, 101 new substances were reported for the first time in the EU (2). Methoxetamine, an NPS, is a dissociative hallucinogenic acting as a NMDA receptor antagonist, clinically and pharmacologically similar to Ketamine (3). It differs from ketamine on its higher potency and duration as well as on its possible serotonergic activity, probably leading to more severe side effects. It has been one of the 6 substances requiring risk assessment by EMCDDA during 2014(3), and several case reports have described fatal outcomes related with its use(4). Objective Material and methods The aim of this study was 1) to explore the presence of methoxetamine from the All samples analyzed from January 2010 to March 2015 in which methoxetamine was samples handled to, and analyzed by Energy Control and 2) to determine whether found were studied. -

Texas Controlled Substances Act

HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE TITLE 6. FOOD, DRUGS, ALCOHOL, AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES SUBTITLE C. SUBSTANCE ABUSE REGULATION AND CRIMES CHAPTER 481. TEXAS CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT SUBCHAPTER A. GENERAL PROVISIONS Sec.A481.001.AASHORT TITLE. This chapter may be cited as the Texas Controlled Substances Act. Acts 1989, 71st Leg., ch. 678, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1989. Sec.A481.002.AADEFINITIONS. In this chapter: (1)AA"Administer" means to directly apply a controlled substance by injection, inhalation, ingestion, or other means to the body of a patient or research subject by: (A)AAa practitioner or an agent of the practitioner in the presence of the practitioner; or (B)AAthe patient or research subject at the direction and in the presence of a practitioner. (2)AA"Agent" means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the direction of a manufacturer, distributor, or dispenser. The term does not include a common or contract carrier, public warehouseman, or employee of a carrier or warehouseman acting in the usual and lawful course of employment. (3)AA"Commissioner" means the commissioner of state health services or the commissioner 's designee. (4)AA"Controlled premises" means: (A)AAa place where original or other records or documents required under this chapter are kept or are required to be kept; or (B)AAa place, including a factory, warehouse, other establishment, or conveyance, where a person registered under this chapter may lawfully hold, manufacture, distribute, dispense, administer, possess, or otherwise dispose of a controlled substance or other item governed by the federal Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. -

Moves to Amend HF No. 2128 As Follows: Delete Everything After

04/05/21 10:32 am HOUSE RESEARCH RC/MV H2128DE1 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 2128 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 DHS HEALTH CARE PROGRAMS 1.5 Section 1. [62A.002] APPLICABILITY OF CHAPTER. 1.6 Any benefit or coverage mandate included in this chapter does not apply to managed 1.7 care plans or county-based purchasing plans when the plan is providing coverage to state 1.8 public health care program enrollees under chapter 256B or 256L. 1.9 Sec. 2. Minnesota Statutes 2020, section 62C.01, is amended by adding a subdivision to 1.10 read: 1.11 Subd. 4. Applicability. Any benefit or coverage mandate included in this chapter does 1.12 not apply to managed care plans or county-based purchasing plans when the plan is providing 1.13 coverage to state public health care program enrollees under chapter 256B or 256L. 1.14 Sec. 3. Minnesota Statutes 2020, section 62D.01, is amended by adding a subdivision to 1.15 read: 1.16 Subd. 3. Applicability. Any benefit or coverage mandate included in this chapter does 1.17 not apply to managed care plans or county-based purchasing plans when the plan is providing 1.18 coverage to state public health care program enrollees under chapter 256B or 256L. 1.19 Sec. 4. [62J.011] APPLICABILITY OF CHAPTER. 1.20 Any benefit or coverage mandate included in this chapter does not apply to managed 1.21 care plans or county-based purchasing plans when the plan is providing coverage to state 1.22 public health care program enrollees under chapter 256B or 256L. Article 1 Sec. -

Control Substance List

Drugs DrugID SubstanceName DEANumbScheNarco OtherNames 1 1-(1-Phenylcyclohexyl)pyrrolidine 7458 I N PCPy, PHP, rolicyclidine 2 1-(2-Phenylethyl)-4-phenyl-4-acetoxypiperidine 9663 I Y PEPAP, synthetic heroin 3 1-[1-(2-Thienyl)cyclohexyl]piperidine 7470 I N TCP, tenocyclidine 4 1-[1-(2-Thienyl)cyclohexyl]pyrrolidine 7473 I N TCPy 5 13Beta-ethyl-17beta-hydroxygon-4-en-3-one 4000 III N 6 17Alpha-methyl-3alpha,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androstane 4000 III N 7 17Alpha-methyl-3beta,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androstane 4000 III N 8 17Alpha-methyl-3beta,17beta-dihydroxyandrost-4-ene 4000 III N 9 17Alpha-methyl-4-hydroxynandrolone (17alpha-methyl-4-hyd 4000 III N 10 17Alpha-methyl-delta1-dihydrotestosterone (17beta-hydroxy- 4000 III N 17-Alpha-methyl-1-testosterone 11 19-Nor-4-androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxyestr-4-ene; 4000 III N 12 19-Nor-4-androstenedione (estr-4-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 13 19-Nor-5-androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxyestr-5-ene; 4000 III N 14 19-Nor-5-androstenedione (estr-5-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 15 1-Androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androst-1- 4000 III N 16 1-Androstenedione (5alpha-androst-1-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 17 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidine 9661 I Y MPPP, synthetic heroin 18 1-Phenylcyclohexylamine 7460 II N PCP precursor 19 1-Piperidinocyclohexanecarbonitrile 8603 II N PCC, PCP precursor 20 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(n)-propylthiophenethylamine 7348 I N 2C-T-7 21 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine 7399 I N DOET 22 2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamine 7396 I N DMA, 2,5-DMA 23 3,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine