Impact Evaluation of the Central Visayas Regional Project Phase I (CVRP-I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 Projects

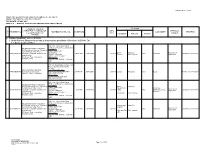

Annual Infrastructure Program Revisions Flag: (D)elisted; (M)odified; (R)ealigned; (T)erminated Operating Unit/ Revisions UACS PAP Project Component Decsription Project Component ID Type of Work Target Unit Target Allocation Implementing Office Flag Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 projects GAA 2016 MFO-1 7,959,170,000 202 projects Bohol 1st District Engineering Office 1,498,045,000 69 projects BOHOL (FIRST DISTRICT) Network Development - Off-Carriageway Improvement including drainage 165003015600115 Tagbilaran East Rd (Tagbilaran-Jagna) - K0248+000 - K0248+412, P00003472VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,609 62,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0248+950 - K0249+696, K0253+000 - K0253+215, K0253+880 - Improvement: Shoulder K0254+701 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Paving / Construction Construction 165003015600117 Tagbilaran North Rd (Tagbilaran-Jetafe Sect) - K0026+000 - K0027+ P00003476VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,828 49,500,000 Bohol 1st District 540, K0027+850 - K0028+560 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office 165003015600225 Jct (TNR) Cortes-Balilihan-Catigbian-Macaas Rd - K0009+-130 - P00003653VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 9,777 91,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0010+382, K0020+000 - K0021+745 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 165003015600226 Jct. (TNR) Maribojoc-Antequera-Catagbacan (Loon) - K0017+445 - P00015037VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 3,141 32,000,000 Bohol 1st District K0018+495 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office Construction and Maintenance of Bridges along National Roads - Retrofitting/ Strengthening of Permanent Bridges 165003016100100 Camayaan Br. -

Icc-Wcf-Competition-Negros-Oriental-Cci-Philippines.Pdf

World Chambers Competition Best job creation and business development project Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry The Philippines FINALIST I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry Inc. (NOCCI), being the only recognized voice of business in the Province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, developed the TIP PROJECT or the TRADE TOURISM and INVESTMENT PROMOTION ("TIP" for short) PROJECT to support its mission in conducting trade, tourism and investment promotion, business development activities and enhancement of the business environment of the Province of Negros Oriental. The TIP Project was conceptualized during the last quarter of 2013 and was launched in January, 2014 as the banner project of the Chamber to support its new advocacy for inclusive growth and local economic development through job creation and investment promotion. The banner project was coined from the word “tip” - which means giving sound business advice or sharing relevant information and expertise to all investors, businessmen, local government officials and development partners. The TIP Project was also conceptualized to highlight the significant role and contribution of NOCCI as a champion for local economic development and as a banner project of the Chamber to celebrate its Silver 25th Anniversary by December, 2016. For two years, from January, 2015 to December, 2016, NOCCI worked closely with its various partners in local economic development like the Provincial Government, Local Government Units (LGUs), National Government Agencies (NGAs), Non- Government Organizations (NGOs), Industry Associations and international funding agencies in implementing its various job creation programs and investment promotion activities to market Negros Oriental as an ideal investment/business destination for tourism, retirement, retail, business process outsourcing, power/energy and agro-industrial projects. -

PESO-Region 7

REGION VII – PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT SERVICE OFFICES PROVINCE PESO Office Classification Address Contact number Fax number E-mail address PESO Manager Local Chief Executive Provincial Capitol , (032)2535710/2556 [email protected]/mathe Cebu Province Provincial Cebu 235 2548842 [email protected] Mathea M. Baguia Hon. Gwendolyn Garcia Municipal Hall, Alcantara, (032)4735587/4735 Alcantara Municipality Cebu 664 (032)4739199 Teresita Dinolan Hon. Prudencio Barino, Jr. Municipal Hall, (032)4839183/4839 Ferdinand Edward Alcoy Municipality Alcoy, Cebu 184 4839183 [email protected] Mercado Hon. Nicomedes A. de los Santos Municipal Alegria Municipality Hall, Alegria, Cebu (032)4768125 Rey E. Peque Hon. Emelita Guisadio Municipal Hall, Aloquinsan, (032)4699034 Aloquinsan Municipality Cebu loc.18 (032)4699034 loc.18 Nacianzino A.Manigos Hon. Augustus CeasarMoreno Municipal (032)3677111/3677 (032)3677430 / Argao Municipality Hall, Argao, Cebu 430 4858011 [email protected] Geymar N. Pamat Hon. Edsel L. Galeos Municipal Hall, (032)4649042/4649 Asturias Municipality Asturias, Cebu 172 loc 104 [email protected] Mustiola B. Aventuna Hon. Allan L. Adlawan Municipal (032)4759118/4755 [email protected] Badian Municipality Hall, Badian, Cebu 533 4759118 m Anecita A. Bruce Hon. Robburt Librando Municipal Hall, Balamban, (032)4650315/9278 Balamban Municipality Cebu 127782 (032)3332190 / Merlita P. Milan Hon. Ace Stefan V.Binghay Municipal Hall, Bantayan, melitanegapatan@yahoo. Bantayan Municipality Cebu (032)3525247 3525190 / 4609028 com Melita Negapatan Hon. Ian Escario Municipal (032)4709007/ Barili Municipality Hall, Barili, Cebu 4709008 loc. 130 4709006 [email protected] Wilijado Carreon Hon. Teresito P. Mariñas (032)2512016/2512 City Hall, Bogo, 001/ Bogo City City Cebu 906464033 [email protected] Elvira Cueva Hon. -

Southern Philippines Irrigation Sector Project

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan for the Dauin Small Reservoir Irrigation Project Final Project Number: 27245 April 2005 PHI: Southern Philippines Irrigation Sector Project Prepared by: National Irrigation Administration; PRIMEX The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Republic of the Philippines NATIONAL IRRIGATION ADMINISTRATION (Pambansang Pangasiwaan ng Patubig) Southern Philippines Irrigation Sector Project (SPISP) (ADB Loan No. 1668-PHI) LLAANNDD ACCQQUUIISSIITTIIOONN AND RESETTLEMENT PLAN DAUIN SMALL RESERVOIR IRRIGATION PROJECT APRIL 2005 SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES IRRIGATION SECTOR PROJECT LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT PLAN (LARP) FOR THE DAUIN SMALL RESERVOIR IRRIGATION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iii List of Tables iv List of Annexes v List of Acronyms vi Executive Summary viii INTRODUCTION 1 Background of the Project General Project Description Dam and Reservoir Areas Irrigation Service Areas 2.0 IMPACT BASELINE INFORMATION AND SOCIOECONOMIC CENSUS 7 2.1 Impacts on Assets and People 2.2 Socio-economic Census 3.0 DETAILED COMPENSATION AND REHABILITATION STRATEGY 12 3.1 Service Area 3.1.1 Equity aspect of the LAR Compensation Scheme for Beneficiary PAPs 3.1.2 Cash Compensation for Non-beneficiary PAPs 3.1.3 Compensation for Donation by Non-beneficiary PAPs 3.1.4 ROW Acquisition 3.2 Reservoir and Dam Area 3.2.1 Process of PAPs Identification, -

DENR-7 DIRECTORY of OFFICIALS As of September 22, 2020

DENR-7 DIRECTORY OF OFFICIALS As of September 22, 2020 OFFICE OFFICIAL OFFICE TEL. NO. E-MAIL ADDRESS OFFICE LOCATION (032) 328-3335/328- Regional Office, Government Center, Sudlon, Lahug, Cebu Office of the Regional Executive Director Paquito D. Melicor, Jr., CESO IV [email protected] 3336 City (032) 345-3905/ [email protected] Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), RD Lormelyn E. Claudio Greenplains Subd., Banilad, Mandaue City 346-1647 [email protected] Mines & Geosciences Bureau (MGB), RD Armando L. Malicse (032) 344-3047 [email protected] Greenplains Subd., Banilad, Mandaue City Coastal, Resources and Ecotourism Research, (032) 346-2209 / Dr. Alicia L. Lustica [email protected] Greenplains Subd., Banilad, Mandaue City Development and Extension Center (CRERDEC) 346-2271 ARD for Management Services Engr. Trinidad C. Etulle (032)328-3337 [email protected] Regional Office, Lahug, Cebu City ARD for Technical Services For. Eduardo M. Inting (032) 328-7474 [email protected] Regional Office, Lahug, Cebu City PENRO Bohol Charlie E. Fabre (038) 411-0228 [email protected] Cortes, Bohol PENRO Bohol Management Services Division Luisito Babaran (038) 416-0147 Cortes, Bohol PENRO Bohol Technical Services Division Candido Salces (038) 416-0151 [email protected] Cortes, Bohol [email protected] / CENRO Tagbilaran City For. Ariel N. Rica (038) 411-2357 New Capitol Site, Tagbilaran City, Bohol [email protected] CENRO Talibon For. Elpidio R. Palaca, Sr. 09173246520 [email protected] San Jose, Talibon, Bohol PENRO Cebu For. Jose Cleo Cary F. Colis (032) 236-5732 [email protected] Greenplains Subd., Banilad, Mandaue City PENRO Cebu Technical Services Division For. -

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (City) Basay Bayawan (City) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (City)Guihulngan (City) Jimalalud L

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (city) Basay Bayawan (city) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (city)Guihulngan (city) Jimalalud Libertad Manjuyod San Jose Santa Catalina Siaton Sibulan Tanjay (city) Tayasan Vallenermoso Zamboanguita 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1.2 Ordinance on MCS Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No N/A No No Yes No Yes No No No No No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes 1.3b Existence of Ordinance No No No No No No Yes No No N/A No No Yes No No No No No No Yes 1.4a CRM Plan Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes 1.4b ICM Plan Yes No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.4c CWUP No No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.5 Water Delineation Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No N/A Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes No Yes No No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes 1.8a Licensing of Gears Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes No -

A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned Pursuant to the Pertinent Provisions of Section 4 of EO No

ANNEX B Page 1 of 105 MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO. VII MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF MAY, 2017 ANNEX B - MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) TENEMENT HOLDER/ LOCATION line PRESIDENT/ CHAIRMAN OF AREA PREVIOUS TENEMENT NO. ADDRESS/FAX/TEL. NO. DATE FILED COMMODITY REMARKS no. THE BOARD/CONTACT (has.) Barangay/s Mun./City Province HOLDER PERSON A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned pursuant to the pertinent provisions of Section 4 of EO No. 79) 1.1. By the Regional Office 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. Paul Vincent Arcenas - President Tinaan, Naga, Cebu Contact Person: Atty. Elvira C. Contact Nos.: Bairan Naga City Apo Cement 1 APSA000011VII Oquendo - Corporate Secretary and 06/03/1991 10/02/2009 240.0116 Cebu Limestone Returned on 03/31/2016 (032)273-3300 to 09 Tananas San Fernando Corporation Legal Director FAX No. - (032)273-9372 Mr. Gery L. Rota - Operations Manila Office: Manager (Cebu) (632)849-3754; FAX No. - (632)849- 3580 6th Floor, Quad Alpha Centrum, 125 Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Tel. Nos. Atlas Consolidated Mining & Cebu Office (Mine Site): 2 APSA000013VII Development Corporation (032) 325-2215/(032) 467-1408 06/14/1991 01/11/2008 287.6172 Camp-8 Minglanilla Cebu Basalt Returned on 03/31/2016 Alfredo C. Ramos - President FAX - (032) 467-1288 Manila Office: (02)635-2387/(02)635-4495 FAX - (02) 635-4495 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. -

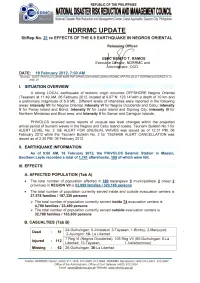

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No.21 on Negros 6.9 Earthquake As Of

C. STATUS OF ROADS AND BRIDGES AND OTHER PUBLIC AND PRIVATE STRUCTURES The estimated total cost of damages incurred by both passable and impassable roads and bridges, public buildings, and flood control structures was pegged PHP 383,059,000.00 INFRASTRUCTURE Region/Province/ PUBLIC TOTAL COST City/Municipality ROADS BRIDGES BUILDINGS GRAND TOTAL 116,825,000.00 168,034,000.00 98,200,000.00 383,059,000.00 Region VI 1,200,000.00 1,200,000.00 Negros Occidental 1,200,000.00 1,200,000.00 Region VII 116,825,000.00 168,034,000.00 97,000,000.00 381,859,000.00 Cebu 1,950,000.00 15,750,000.00 17,700,000.00 Negros Oriental 114,875,000.00 152,284,000.00 97,000,000.00 364,159,000.00 • IMPASSABLE BRIDGES: Two (2) bridges in Negros Oriental remain impassable due to collapsed span of Martilo Bridge in La Libertad and collapsed center span of Pangaloan Bridge in Jimalalud . Delivery of bailey panels from other District Engineering Offices is scheduled for use in the construction of detour bridges. • IMPASSABLE ROAD: One (1) road section along Dumaguete North road remains inaccessible due to cracks/ cuts, rockfalls, landslides and road slips. Restoration works are ongoing. D. DAMAGED HOUSES (Tab C) • A total of 15,787 houses were damaged (Totally – 6,352 / Partially – 9,435) E. STATUS OF LIFELINES • NGCP restored power transmission services in parts of Negros Oriental affected by earthquake. As of 1:56PM, 11 February 2012 normal operations of the Negros sub-grid was restored after completion of repairs and re-energization of the Bindoy-Guihulngan 69-kV transmission line • As of 9 February 2012, some portions of La libertad and Jimalalud were already energized thru the efforts of the National Grid Corp. -

Tañon Strait

Love Letter to TAÑON STRAIT Stacy K. Baez, Ph.D., Charlotte Grubb, Margot L. Stiles and Gloria Ramos Tañon Strait PROTECTED SEASCAPE Bantayan Santa Fe Daanbantayan Medellin The Largest Marine Protected Area Visayan Sea IN THE PHILIPPINES San Remigio Cadiz Sagay Escalante Tabuela Tuburan Toboso Bacolod Asturias San Carlos Balambam Vallehermoso Toledo Cebu Pinamungahan Aloguinsan Gulhulngan Barili La Libertad Dumanjug Aloguinsan Jimalalud Ronda Tayasan Pescador Island Moalboal Ayungon Badian Bindoy Mantalip Reef Alegria Manjuyod Malabuyoc Bais Ginatilan Talabong Mangrove Park Tanjay Samboan Pamplona Amlan Santander San Jose Sibulan Dumaguete Bohol Sea 1 PH.OCEANA.ORG Modified from L. Aragones Introduction Bantayan Santa Fe Daanbantayan Medellin The Largest Marine Protected Area Visayan Sea IN THE PHILIPPINES San Remigio Cadiz Sagay Escalante Tabuela añon Strait Protected Seascape Colorful bangkas grace blue waters is the largest marine protected teeming with fish, and thatched roof Tuburan Toboso Tarea in the Philippines, and the nipa huts shelter families of farmers Bacolod third largest park, nearly as extensive as and fisherfolk all along the shorelines the two largest terrestrial natural parks of Negros and Cebu. Tañon Strait was Asturias in the Northern Sierra Madre and Samar declared a protected seascape in 1998, Island which protect the Philippine in honor of the 14 species of whales and Balambam San Carlos Eagle and other wonders. Tañon Strait dolphins which live within this special is their marine counterpart, with an area place. Several of the Philippines’ most 2 Vallehermoso Toledo of 5,182 km , more than three times the ancient and endangered animals have area of the Tubbataha National Park. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 5

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 555 Dangay 798 East Poblacion 1,829 Ponong 1,121 San Agustin 526 Santa Filomena 911 Tagbuane 888 Toril 706 West Poblacion 1,041 ALICIA 22,285 Cabatang 675 Cagongcagong 423 Cambaol 1,087 Cayacay 1,713 Del Monte 806 Katipunan 2,230 La Hacienda 3,710 Mahayag 687 Napo 1,255 Pagahat 586 Poblacion (Calingganay) 4,064 Progreso 1,019 Putlongcam 1,578 Sudlon (Omhor) 648 Untaga 1,804 ANDA 16,909 Almaria 392 Bacong 2,289 Badiang 1,277 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Buenasuerte 398 Candabong 2,297 Casica 406 Katipunan 503 Linawan 987 Lundag 1,029 Poblacion 1,295 Santa Cruz 1,123 Suba 1,125 Talisay 1,048 Tanod 487 Tawid 825 Virgen 1,428 ANTEQUERA 14,481 Angilan 1,012 Bantolinao 1,226 Bicahan 783 Bitaugan 591 Bungahan 744 Canlaas 736 Cansibuan 512 Can-omay 721 Celing 671 Danao 453 Danicop 576 Mag-aso 434 Poblacion 1,332 Quinapon-an 278 Santo Rosario 475 Tabuan 584 Tagubaas 386 Tupas 935 Ubojan 529 Viga 614 Villa Aurora (Canoc-oc) 889 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and -

Fisheries Profile of Negros Oriental Province

Fisheries Profile of Negros Oriental Province Negros Oriental occupies the south-eastern half of the island of Negros, with Negros Occidental comprising the north-western half. It has a total land area of 5,385.53 square kilometres (2,079.36 sq mi). [11] A chain of rugged mountains separates Negros Oriental from Negros Occidental. Negros Oriental faces Cebu to the east across the Tañon Strait and Siquijor to the southeast. The Sulu Sea borders it to the south to southwest. The population of Negros Oriental in the 2015 census was 1,354,995 people,[2] with a density of 250 inhabitants per square kilometre or 650 inhabitants per square mile. Its registered voting population are 606,634.[19] 34.5% of the population are concentrated in the six most populous component LGUs of Dumaguete City, Bayawan City, Guihulngan City, Tanjay City, Bais City and Canlaon City. Population growth per year is about 0.99% over the period 2010-2015, lower than the national average of 1.72%.[2] Residents of Negros are called "Negrenses" (and less often "Negrosanons") and many are of either pure/mixedAustronesian heritage, with foreign ancestry as minorities. Negros Oriental is predominantly a Cebuano-speaking province by 77%, due to its close proximity to Cebu. Hiligaynon/Ilonggo is spoken by the remaining 23% and is common in areas close to the border with Negros Occidental. Filipino and English, though seldom used, are generally understood and used for official, literary and educational purposes. Population census of Negros Oriental Year Pop. ±% p.a. 1990 925,272 — 1995 1,025,247 +1.94% 2000 1,130,088 +2.11% 2007 1,231,904 +1.20% 2010 1,286,666 +1.60% 2015 1,354,995 +0.99% Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [2][16][16] Negros Oriental comprises 19 municipalities and 6 cities, further subdivided into 557 barangays. -

RISING TIDE Understanding the Fiscal Capacity of 75 Philippine Local Government Units for Sustainable Coastal Fisheries Financing

RISING TIDE Understanding the Fiscal Capacity of 75 Philippine Local Government Units for Sustainable Coastal Fisheries Financing PREPARED BY SUPPORTED BY RISING TIDE Understanding the Fiscal Capacity of 75 Philippine Local Government Units for Sustainable Coastal Fisheries Financing TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 Preface 03 Executive Summary 04 Chapter 1. Government Revenue 10 Chapter 2. Government Spending 15 Chapter 3. Debt Capacity 18 Chapter 4. Loans and Grants History 19 Chapter 5. Regulatory Fee Structure 20 Chapter 6. Funding for Small-Scale Fisheries 21 Chapter 7. Capacity-Building Opportunities 22 Conclusion 23 References 2 | RISING TIDE: A FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF 75 LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS Preface ore than 1.8 million improve the ecological and social resilience of Filipinos rely on fishing coastal communities. for their livelihood, and To guide more effective interventions, PREFACEDOF- fish and fish products BLGFMore thanand Rare1.8 millionjointly conductedFilipinos rely a studyon fishing to for their livelihood, and fish and fish products comprise almost 12% facilitatecomprise better almost understanding 12% of the average of the currentFilipino diet, a proportion that is significantly higher than of the average Filipino fiscalmeat and capacity chicken. including Unfortunately, borrowing the capacity, fish catch necessary to provide for Filipino families have diet, a proportion that regulatorybeen steadily fee decliningstructure since and abilitythe 1970s to manage and ha s resulted in a vicious cycle of overfishing and is significantly higher than meat and chicken. loansother ofunsustainable 75 coastal LGUs fishing in practices.the Philippines. If left Thisunaddressed, a collapse in fisheries resource is inevitable, posing a serious threat to both the livelihoods of coastal communities and food security MUnfortunately, the fish catch necessary to provide report has been prepared solely for informational of the nation.