The Survivors of the Holocaust in Occupied Germany Zeev W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAI News Fall 2018

CENTER FOR HOLOCAUST October 2018 AWARENESS AND INFORMATION (CHAI) CHAI update Tishri-Cheshvan 5779 80 YEARS AFTER KRISTALLNACHT: Remember and Be the Light Thursday, November 8, 2018 • 7—8 pm Fabric of Survival for Educators Temple B’rith Kodesh • 2131 Elmwood Ave Teacher Professional Development Program Kristallnacht, also known as the (Art, ELA, SS) Night of Broken Glass, took place Wednesday, October 3 on November 9-10, 1938. This 4:30—7:00 pm massive pogrom was planned Memorial Art Gallery and carried out 80 years ago to terrorize Jews and destroy Jewish institutions (synagogues, schools, etc.) throughout Germa- ny and Austria. Firefighters were in place at every site but their duty was not to extinguish the fire. They were there only to keep the fire from spreading to adjacent proper- ties not owned by Jews. A depiction of Passover by Esther Historically, Kristallnacht is considered to be the harbinger of the Holocaust. It Nisenthal Krinitz foreshadowed the Nazis’ diabolical plan to exterminate the Jews, a plan that Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Holocaust succeeded in the loss of six million. survivor, uses beautiful and haunt- ing images to record her story when, If the response to Kristallnacht had been different in 1938, could the Holocaust at age 15, the war came to her Pol- have been averted? Eighty years after Kristallnacht, what are the lessons we ish village. She recounts every detail should take away in the context of today’s world? through a series of exquisite fabric collages using the techniques of em- This 80 year commemoration will be a response to these questions in the form broidery, fabric appliqué and stitched of testimony from local Holocaust survivors who lived through Kristallnacht, narrative captioning, exhibited at the as well as their direct descendents. -

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

American Jewish Philanthropy and the Shaping of Holocaust Survivor Narratives in Postwar America (1945 – 1953)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 © Copyright by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) by Rachel Beth Deblinger Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor David N. Myers, Chair The insistence that American Jews did not respond to the Holocaust has long defined the postwar period as one of silence and inaction. In fact, American Jewish communal organizations waged a robust response to the Holocaust that addressed the immediate needs of survivors in the aftermath of the war and collected, translated, and transmitted stories about the Holocaust and its survivors to American Jews. Fundraising materials that employed narratives about Jewish persecution under Nazism reached nearly every Jewish home in America and philanthropic programs aimed at aiding survivors in the postwar period engaged Jews across the politically, culturally, and socially diverse American Jewish landscape. This study examines the fundraising pamphlets, letters, posters, short films, campaign appeals, radio programs, pen-pal letters, and advertisements that make up the material record of this communal response to the Holocaust and, ii in so doing, examines how American Jews came to know stories about Holocaust survivors in the early postwar period. This kind of cultural history expands our understanding of how the Holocaust became part of an American Jewish discourse in the aftermath of the war by revealing that philanthropic efforts produced multiple survivor representations while defining American Jews as saviors of Jewish lives and a Jewish future. -

Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1

1 Proposed Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.4.HE.1.1 Compare and contrast Judaism to other major religions observed around the world, and in the United States and Florida. Grade 5 Standard 1: SS.5.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.5.HE.1.1 Define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of the Jewish people. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Teachers will provide students with an age-appropriate definition of with the Holocaust. Grades 6-8 Standard 1: SS.68.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.68.HE.1.1 Define the Holocaust as the planned and systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Students will define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of Jewish people. Grades 9-12 Standard 1: SS.HE.912.1. Analyze the origins of antisemitism and its use by the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi) regime. SS.912.HE.1.1 Define the terms Shoah and Holocaust. Students will distinguish how the terms are appropriately applied in different contexts. SS.912.HE.1.2 Explain the origins of antisemitism. Students will recognize that the political, social and economic applications of antisemitism led to the organized pogroms against Jewish people. Students will recognize that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are a hoax and utilized as propaganda against Jewish people both in Europe and internationally. -

Jewish Survivors of the Holocaust Residing in the United States

Jewish Survivors of the Holocaust Residing in the United States Estimates & Projections: 2010 - 2030 Ron Miller, Ph. D. Associate Director Berman Institute-North American Jewish Data Bank Pearl Beck, Ph.D. Director, Evaluation Ukeles Associates, Inc. Berna Torr, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Sociology California State University-Fullerton October 23, 2009 CONTENTS AND TABLES Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………….….3 Definitions Data Sources Interview Numbers: NJPS and New York US Nazi Survivor Estimates 2010-2030: Total Number of Survivors and Gender………………6 Table 1: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Total Number of Survivors, by Gender……………………………………………………....7 US Nazi Survivor Estimates 2010-2030: Total Number of Survivors and Age Patterns..………9 Table 2: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Total Number of Survivors, by Age………………………………………………………….10 Poverty: US Nazi Survivors: 2010-2030…………………………….………………………....……11 Table 3: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number of Survivors Below Poverty Thresholds ………………………………………….12 Disability: US Nazi Survivors: 2010-2030…………………………….……………………….....….13 Table 4: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number of Survivors with a Disabling Health Condition ………………………………….14 Severe Disability………………….………………………………………………...…....……15 Table 5: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number and Percentage of Disabled Survivors Who May Be Severely Disabled ….....17 Disability and Poverty: -

History of the Holocaust

HISTORY OF THE HOLOCAUST: AN OVERVIEW On January 20, 1942, an extraordinary 90-minute meeting took place in a lakeside villa in the wealthy Wannsee district of Berlin. Fifteen high-ranking Nazi party and German government leaders gathered to coordinate logistics for carrying out “the final solution of the Jewish question.”Chairing the meeting was SS Lieutenant General Reinhard Heydrich, head of the powerful Reich Security Main Office, a central police agency that included the Secret State Police (the Gestapo). Heydrich convened the meeting on the basis of a memorandum he had received six months earlier from Adolf Hitler’s deputy, Hermann Göring, confirming his authorization to implement the “Final Solution.” The “Final Solution” was the Nazi regime’s code name for the deliberate, planned mass murder of all European Jews. During the Wannsee meeting German government officials discussed “extermi- nation” without hesitation or qualm. Heydrich calculated that 11 million European Jews from more than 20 countries would be killed under this heinous plan. During the months before the Wannsee Conference, special units made up of SS, the elite guard of the Nazi state, and police personnel, known as Einsatzgruppen, slaughtered Jews in mass shootings on the territory of the Soviet Union that the Germans had occupied. Six weeks before the Wannsee meeting, the Nazis began to murder Jews at Chelmno, an agricultural estate located in that part of Poland annexed to Germany.Here SS and police personnel used sealed vans into which they pumped carbon monoxide gas to suffocate their victims.The Wannsee meeting served to sanction, coordinate, and expand the implementation of the “Final Solution” as state policy. -

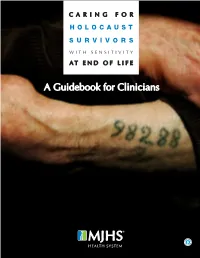

A Guidebook for Clinicians CARING for HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS with SENSITIVITY at END of LIFE

CARING FOR HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS WITH SENSITIVITY AT END OF LIFE A Guidebook for Clinicians CARING FOR HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS WITH SENSITIVITY AT END OF LIFE Dear Colleagues, As clinicians and professional caregivers whose mission it is to manage pain and suffering, we are bound by an oath to “do no harm” and to provide culturally sensitive care. When providing services to Holocaust Survivors and war victims, it is important that we are mindful of our words and actions—particularly because we may be the last generation of caregivers and clinicians who have the honor, as well as the moral obligation, of delivering compassionate health services to Survivors. As one of the largest hospice programs under Jewish auspices in the region, MJHS understands that members of the Jewish community have different levels of observance, and so we tailor our hospice program to meet the individual spiritual and religious practices of each patient. For those who wish to participate, we offer the Halachic Pathway—which is funded by MJHS Foundation and ensures that end-of-life decisions are made in concert with a patient’s rabbinic advisor and adhere to Jewish law and traditions. Our sensitive care to Holocaust Survivors and their families takes into consideration the unique physical, emotional, social and psychological pain and discomfort they experience when facing the end of life. This is one of the many reasons why we seek to share our insights and experiences. This guidebook is for clinicians who have never, or rarely, worked with Holocaust Survivors. It is meant to help users gain a deeper understanding of end-of-life issues that may manifest in the Holocaust Survivor patient, especially ones that can be easily misunderstood or misinterpreted. -

Liberation from Concentration Camps: the Complexity of Concluding the Holocaust Narrative NINA KOVALENKO

Primary Source Volume I: Issue I Page 35 Liberation from Concentration Camps: The Complexity of Concluding the Holocaust Narrative NINA KOVALENKO t is certainly tempting to look for a clear beginning, middle, and end in every story. When depicting the Holocaust, Ichoosing to end the story with the liberation of inmates from concentration camps can be all too satisfying: after all, the experience must have been a joyful one for those survivors who triumphed over Nazi evil. However, this is a much oversimplified way of looking at liberation. Though many Holocaust survivors felt euphoric upon being freed, liberation was not a neat, happy conclusion of their suffering. Many survivors experienced and witnessed illness due to intense deprivation after the Nazis left the camps. Additionally, liberation aroused a range of conflicting emotions in survivors. In early post-war testimony, survivors discuss how they sought to get revenge on their persecutors after liberation. By contrast, in later memoirs, survivors tend to focus on the hopelessness, fear of the future, and revival of numbed feelings that freedom brought. This disparity in the aspects of the experience that survivors choose to emphasize suggests that the complexity lies not only in the reality of the experience, but also in trying to uncover it. Every testimony is shaped in part by the context in which it is given and its intended audience. As the survivors’ vantage points shift, they present their stories in different ways. Thus, in order to understand the differences in contemporary and later reflections, the survivors’ vantage points must be kept in mind. -

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria Subsidizes Scientific And

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria subsidizes scientific and pedagogical projects which foster tolerance and mutual understanding on the basis of a close examination of the sufferings caused by the Nazi regime on the territory of present-day Austria. Keeping alive the memory of the victims as a reminder for future generations is one of our main targets, as well as human rights education and the strengthening of democratic values. Beyond, you will find a list containing the English titles or brief summaries of all projects approved by the Future Fund since its establishment in 2006. For further information in German about the content, duration and leading institutions or persons of each project, please refer to the database (menu: “Projektdatenbank”) on our homepage http://www.zukunftsfonds-austria.at If you have further questions, please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] Project-Code P06-0001 brief summary Soviet Forced Labour Workers and their Lives after Liberation Project-Code P06-0002 brief summary Life histories of forced labour workers under the Nazi regime Project-Code P06-0003 brief summary Unbroken Will - USA - Tour 2006 (book presentations and oral history debates with Holocaust survivor Leopold Engleitner) Project-Code P06-0004 brief summary Heinrich Steinitz - Lawyer, Poet and Resistance Activist Project-Code P06-0006 brief summary Robert Quintilla: A Gaul in Danubia. Memoirs of a former French forced labourer Project-Code P06-0007 brief summary Symposium of the Jewish Museum Vilnius on their educational campaign against anti-Semitism and Austria's contribution to those efforts Project-Code P06-0008 brief summary Effective Mechanisms of Totalitarian Developments. -

9Th Graders Digitally Meet with Two Holocaust Survivors

9th graders digitally meet with two Holocaust survivors This year, the school library and Bill Brown have served to better the education of our children in many ways, most recently by facilitating a relationship with the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County. Through this relationship, 9th grade World Studies students (led by teacher Chris Mosher) have had the opportunity to teleconference with a Holocaust survivor for the past 4 years. This year, on May 26 and May 28, we continued that tradition by meeting two Holocaust survivors: Werner Reich (pictured below) and Kathy Griesz. Students gathered on Google Meets to hear their testimonies and ask questions about their experience in the Holocaust. Kathy Griesz was born and raised in Budapest, Hungary, and was 13 when Nazi Germany invaded. Along with the rest of the Jewish population of Budapest, she and her family were stripped of their property, money, and belongings (which would never be recovered), and forced into the Budapest Ghetto. In the ghetto, she was subjected to the Nazi’s dehumanization campaign against the Jews and the everpresent fear of being killed for her family’s religious beliefs. Due to the (relative) late occupation of Hungary by the Nazis, Kathy and her immediate family were spared the horrors of the concentration camps, but much of her extended family were not. Werner Reich was 15 and living in Yugoslavia when he was arrested by the Gestapo after being found hiding with resistance soldiers. Over the next two years, he was transported to multiple concentration camps, before ultimately ending up in Auschwitz. -

Holocaust?Series=48246 WEEK 1 Articles and Questions

Students, here are the next set of assignments for the next 3 weeks. You will not need your text book for this. Instead, use the following articles and questions. These articles are a study on the Holocaust. The questions you will need to answer are found at the very bottom of the pages. Week 1 a) Read the article entitled "Introduction to the Holocaust". When finished answer the critical thinking questions at the bottom of the page. b) Read the article entitled "Liberation of Nazi Camps" and answer the critical thinking questions. Week 2 a) Read the article entitled "Aftermath of the Holocaust" and answer the critical thinking questions at the bottom of the page. b) Read the article entitled "War Crimes Trials" and answer the critical thinking questions. Week 3 a) Read "Displaced Persons" and answer the critical thinking questions. b) Read "What is Genocide" and answer the critical thinking questions. Let me know if you have any questions. Be safe and please practice social distancing! Miss Fischer https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/introduction-to-the- holocaust?series=48246 WEEK 1 Articles and Questions Introduction To The Holocaust The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its allies and collaborators. Holocaust is a word of Greek origin meaning "sacrifice by fire." The Nazis, who came to power in Germany in January 1933, believed that Germans were "racially superior" and that the Jews, deemed "inferior," were an alien threat to the so-called German racial community. During the era of the Holocaust, German authorities also targeted other groups because of their perceived racial and biological inferiority: Roma (Gypsies), people with disabilities, some of the Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, and others), Soviet prisoners of war, and blacks. -

KRISTALLNACHT 1938 As Experienced Then and Understood Now

KRISTALLNACHT 1938 As Experienced Then and Understood Now Gerhard L. Weinberg Kristallnacht 1938 As Experienced Then and Understood Now Gerhard L. Weinberg MONNA AND OTTO WEINMANN ANNUAL LECTURE 13 MAY 2009 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, July 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Gerhard L. Weinberg The Monna and Otto Weinmann Annual Lecture honors Holocaust survivors and their fates, experiences, and accomplishments. Monna Steinbach Weinmann (1906–1991), born in Poland and raised in Austria, fled to England in autumn 1938. Otto Weinmann (1903–1993), born in Vienna and raised in Czechoslovakia; served in the Czechoslovak, French, and British armies; was wounded at Normandy; and received the Croix de Guerre for his valiant contributions during the war. Monna Steinbach and Otto Weinmann married in London in 1941 and emigrated to the United States in 1948. In November 1938 I was two months short of my eleventh birthday, living in Hanover in north-central Germany. My parents, an older sister, an older brother, and I, together with another Jewish couple with their young son, lived on a floor of a building my parents owned in that city. My father had been fired from his government position after President Hindenburg’s death in 1934 and now earned his income advising people who were emigrating about the extremely complicated and frequently changing rules governing the assets they could and could not take with them. Mother was a homemaker. My brother had been so mistreated in school that my parents had sent him to live with a family in Berlin while he attended a Jewish school there.