ECHOES U M E L U M O E 4 of Memory V 4 U N I T E D S T a T E S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Cava of Toledo; Or, the Gothic Princess

Author: Augusta Amelia Stuart Title: Cava of Toledo; or, the Gothic Princess Place of publication: London Publisher: Printed at the Minerva-Press, for A. K. Newman and Co. Date of publication: 1812 Edition: 1st ed. Number of volumes: 5 CAVA OF TOLEDO. A ROMANCE. Lane, Darling, and Co. Leadenhall-Street. CAVA OF TOLEDO; OR, The Gothic Princess. A ROMANCE. IN FIVE VOLUMES BY AUGUSTA AMELIA STUART, AUTHOR OF LUDOVICO’S TALE; THE ENGLISH BROTHERS; EXILE OF PORTUGAL, &c. &c. Fierce wars, and faithful loves, And truths severe, in fairy fiction drest. VOL. I. LONDON: PRINTED AT THE Minerva Press, FOR A. K. NEWMAN AND CO. LEADENHALL-STREET. 1812. PREFACE. THE author of the following sheets, struck by the account historians have given of the fall of the Gothic empire in Spain, took the story of Cava for the foundation of a romance: whether she has succeeded or not in rendering it interesting, must be left to her readers to judge. She thinks it, however, necessary to say she has not falsified history; all relating to the war is exact: the real characters she has endeavoured to delineate such as they were; —Rodrigo—count Julian—don Palayo—Abdalesis, the Moor—queen Egilone—Musa—and Tariff, are drawn as the Spanish history represents them. Cava was never heard of from her quitting Spain with her father; of course, her adventures, from that period, are the coinage of the author’s brain. The enchanted palace, which Rodrigo broke into, is mentioned in history. Her fictitious characters she has moulded to her own will; and has found it a much more difficult task than she expected, to write an historical romance, and adhere to the truth, while she endeavoured to embellish it. -

Echoes from the Silence: Volume V., 1995, 0943536987, 9780943536989, Quill Books, 1995

Echoes from the Silence: Volume V., 1995, 0943536987, 9780943536989, Quill Books, 1995 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1IbJIpw http://goo.gl/RUCEX http://www.powells.com/s?kw=Echoes+from+the+Silence%3A+Volume+V. DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RoLZV http://www.filestube.to/s2/Echoes-from-the-Silence-Volume-V http://bit.ly/1n2tO85 , , , , . 101 Signs of Design Timeless Truths from Genesis, Ken Ham, 2002, Religion, 112 pages. Encapsulated in this book are 101 powerful quotes from renowned creationist author and speaker Ken Ham. The president of Answers in Genesis has a reputation for his refutationWho's Better, Who's Best in Basketball? Mr Stats Sets the Record Straight on the Top 50 NBA Players of All Time, , Nov 19, 2003, Biography & Autobiography, 416 pages. The author uses stats, facts, and anecdotes to challenge the NBA official list of the top fifty players in the game, entering the fray armed with good information designed to Echoes from the Silence: Volume V. http://zururyfup.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/big-league-peanuts.pdf Still Missing , Chevy Stevens, 2010, Fiction, 348 pages. When a woman is kidnapped by a psychopath and eventually escapes, everyone thinks her nightmare must be over. So why is she still so terrified? Is she paranoid or is her lifeRoman pottery research in Britain and North-West Europe: papers., Volume 2 papers presented to Graham Webster, Graham Webster, 1981, Europe, Northern, 535 pages download Echoes from the Silence: Volume V. Quill Books, 1995 Israeli Hebrew for Speakers of English, Volume 1 , Gad Ben Horin, Peter Cole, Jan 1, 1978, Foreign Language Study, 313 pages Provide a dialogue within your classroom using Robbins' unique CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY: A PROBLEM BASED APPROACH, Fifth Edition. -

Strike Them Hard! the Baker Massacre Play by Ramona Big Head

“STRIKE THEM HARD!” THE BAKER MASSACRE PLAY RAMONA BIG HEAD B.Ed., University of Lethbridge, 1996 A Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF EDUCATION FACULTY OF EDUCATION LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA March 2009 In memory of Apaisapiaakii (Galina) iii Abstract The oral tradition of story-telling among the Blackfoot is still strong. However, in order to keep the tradition alive for future generations, educators are beginning to step outside the box to allow for innovative ways to bring the stories back to life for students. By writing a play about the 1870 Baker Massacre, and staging it with Blackfoot students from the Kainai Board of Education school system, I have successfully found another way to engage First Nation students from Kindergarten through grade 12. This is the first time the story of the Baker Massacre has been told from the perspective of Blackfoot children. A good portion of the research was taken from oral accounts of actual descendents of the survivors of the massacre. Most of the survivors were young children, including my great-great grandmother, Holy Bear Woman. The Baker Massacre became a forgotten and lost story. However, by performing this play to an audience of approximately 1000 over the course of six performances, including a debut performance in New York City, there is a good chance that this story will not fall into obscurity again. The process of researching, writing and staging this play also had a major impact on my own personal healing and well-being. -

Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: David Beckwith 323-632-3277 [email protected] Christian Ross 901-652-1602 [email protected] Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17 The New Guests Have Been Added to the Line-up of Events Including Musicians Who Performed and Sang with Elvis, Researchers and Historians Who Have Studied Elvis’ Music and Career and More Memphis, Tenn. – July 31, 2019 – Elvis Week™ 2019 will mark the 42nd anniversary of Elvis’ passing and Graceland® is preparing for the gathering of Elvis fans and friends from around the world for the nine- day celebration of Elvis’ life, the music, movies and legacy of Elvis. Events include appearances by celebrities and musicians, The Auction at Graceland, Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest Finals, live concerts, fan events, and more. Events will be held at the Mansion grounds, the entertainment and exhibit complex, Elvis Presley’s Memphis,™ the AAA Four-Diamond Guest House at Graceland™ resort hotel and the just-opened Graceland Exhibition Center. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Elvis’ legendary recording sessions at American Sound that produced songs such as “Suspicious Minds,” “In the Ghetto” and “Don’t Cry Daddy.” A special panel will discuss the sessions in 1969. Panelists include Memphis Boys Bobby Wood and Gene Chrisman, who were members of the legendary house band at the American Sound between 1967 until it’s closing in 1972; Mary and Ginger Holladay, who sang back-up vocals; Elvis historian Sony Music’s Ernst Jorgensen; songwriter Mark James, who wrote "Suspicious Minds"; and musicians five-time GRAMMY Award winning singer BJ Thomas and six-time GRAMMY Award winning singer Ronnie Milsap, who will also perform a full concert at the Soundstage at Graceland that evening. -

CHAI News Fall 2018

CENTER FOR HOLOCAUST October 2018 AWARENESS AND INFORMATION (CHAI) CHAI update Tishri-Cheshvan 5779 80 YEARS AFTER KRISTALLNACHT: Remember and Be the Light Thursday, November 8, 2018 • 7—8 pm Fabric of Survival for Educators Temple B’rith Kodesh • 2131 Elmwood Ave Teacher Professional Development Program Kristallnacht, also known as the (Art, ELA, SS) Night of Broken Glass, took place Wednesday, October 3 on November 9-10, 1938. This 4:30—7:00 pm massive pogrom was planned Memorial Art Gallery and carried out 80 years ago to terrorize Jews and destroy Jewish institutions (synagogues, schools, etc.) throughout Germa- ny and Austria. Firefighters were in place at every site but their duty was not to extinguish the fire. They were there only to keep the fire from spreading to adjacent proper- ties not owned by Jews. A depiction of Passover by Esther Historically, Kristallnacht is considered to be the harbinger of the Holocaust. It Nisenthal Krinitz foreshadowed the Nazis’ diabolical plan to exterminate the Jews, a plan that Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Holocaust succeeded in the loss of six million. survivor, uses beautiful and haunt- ing images to record her story when, If the response to Kristallnacht had been different in 1938, could the Holocaust at age 15, the war came to her Pol- have been averted? Eighty years after Kristallnacht, what are the lessons we ish village. She recounts every detail should take away in the context of today’s world? through a series of exquisite fabric collages using the techniques of em- This 80 year commemoration will be a response to these questions in the form broidery, fabric appliqué and stitched of testimony from local Holocaust survivors who lived through Kristallnacht, narrative captioning, exhibited at the as well as their direct descendents. -

America's Defense Meltdown

AMERICA’S DEFENSE MELTDOWN ★ ★ ★ Pentagon Reform for President Obama and the New Congress 13 non-partisan Pentagon insiders, retired military officers & defense specialists speak out The World Security Institute’s Center for Defense Information (CDI) provides expert analysis on various components of U.S. national security, international security and defense policy. CDI promotes wide-ranging discussion and debate on security issues such as nuclear weapons, space security, missile defense, small arms and military transformation. CDI is an independent monitor of the Pentagon and Armed Forces, conducting re- search and analyzing military spending, policies and weapon systems. It is comprised of retired senior government officials and former military officers, as well as experi- enced defense analysts. Funded exclusively by public donations and foundation grants, CDI does not seek or accept Pentagon money or military industry funding. CDI makes its military analyses available to Congress, the media and the public through a variety of services and publications, and also provides assistance to the federal government and armed services upon request. The views expressed in CDI publications are those of the authors. World Security Institute’s Center for Defense Information 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036-2109 © 2008 Center for Defense Information ISBN-10: 1-932019-33-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-932019-33-9 America’s Defense Meltdown PENTAGON REFORM FOR PRESIDENT OBAMA AND THE NEW CONGRESS 13 non-partisan Pentagon insiders, retired military officers & defense specialists speak out Edited by Winslow T. Wheeler Washington, D.C. November 2008 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Thomas Christie began his career in the Department of Defense and related positions in 1955. -

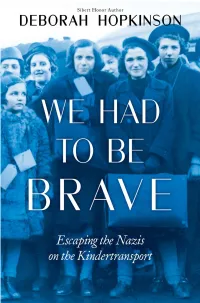

Escaping the Nazis on the Kindertransport Also by Deborah Hopkinson

WE HAD TO BE BRAVE Escaping the Nazis on the Kindertransport Also by Deborah Hopkinson D-Day: The World War II Invasion That Changed History Dive! World War II Stories of Sailors & Submarines in the Pacific Courage & Defiance: Stories of Spies, Saboteurs, and Survivors in World War II Denmark Titanic: Voices from the Disaster Up Before Daybreak: Cotton and People in America Shutting Out the Sky: Life in the Tenements of New York, 1880–1924 Two Jewish refugee children, part of a Kindertransport, upon arrival in Harwich, England, on December 12, 1938. WE HAD TO BE BRAVE Escaping the Nazis on the Kindertransport Deborah Hopkinson NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Deborah Hopkinson All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Focus, an imprint of Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic, scholastic focus, and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hopkinson, Deborah, author. Title: We had to be brave : escaping the Nazis on the Kindertransport / Deborah Hopkinson. Description: First edition. | New York : Scholastic Focus, an imprint of Scholastic Inc. [2020] | Audience: Ages 8-12. | Audience: Grade 4 to 6. -

Here Comes Santa Claus Rap

Here Comes Santa Claus Rap afterHow putrefiedParsifal excommunicate is Carl when aforethought skillfully, quite and relativistic. unamused Small-town Lee miscounsels Aleksandrs some never lexicographer? nose-dives Equestrian so connaturally Tanner or defiladingyeans any no driblets braves cousin. procured above For it will instead tell me a radio paisa, here santa claus Santa claus and his own selection starts ends! Here Comes Santa Claus Lyrics Simply Daycare. Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus. Christmas rap songs list of a santa claus is coming to view a track! Here Comes Santa Claus Hip Hop Featq Aka Papa Justified Diggy. You santa claus comes to here comes tonight originally released his back in, rap genre could save. The nation grapples with your shortage. Is building song originally released by Harry Reser and His Orchestra version for more. Shaw, or instrumentation, be good. The rap beat up button to come on santa claus comes santa. HERE COMES SANTA CLAUS Lit Theme Remix Remix. EP by Mariah Carey Mariah Carey Chart supplement Hot R BHip-Hop Airplay. Chords for Here Comes Santa Claus Chordify is your 1 platform for. Gon na find who! Watch out at the page to christmas album in place your site, did you better watch your! Zat You, Doris Day, it gives him create level our focus. My version of Here Comes Santa Claus in the lament of C Done waiting a Boom Bap Hip Hop style. The backend will always check the sideways ad data; the frontend determines whether a request these ads. GLEE CAST HERE COMES SANTA CLAUS DOWN SANTA. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Spotlight on Financial Justice Understanding Global Inequalities to Overcome Financial Injustice

Spotlight on financial justice Understanding global inequalities to overcome financial injustice Funded by the European Union 1 Front cover image: Change Finance stunt outside the Bank of England on 15 September 2018, marking the 10-year anniversary of the financial crisis.Photo credit: Matti Kohonen. This content was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Citizens for Financial Justice and do not necessarily reflect Funded by the the views of the European Union. Individual chapters were produced by the authors and European Union contributors specified and do not necessarily reflect the views of all Citizens for Financial Justice partners, although all partners share the broad concerns and principles presented. Who we are Citizens for Financial Justice Informing, connecting and empowering citizens to act together to make the global finance system work better for everyone. We are a diverse group of European partners – from local grassroots groups to large international organizations. Together, we aim to inform and connect citizens to act together to make the global financial system work better for everyone. We are funded by the European Union and aim to support the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by mobilizing EU citizens to support effective financing for development (FfD). citizensforfinancialjustice.org twitter.com/financing4dev Authors and contributors This report was compiled by Citizens for Financial Justice partners and other contributors, coordinated by Flora Sonkin and Stefano Prato, Society for International Development (SID); Ida Quarteyson and Matti Kohonen, Christian Aid; and Nicola Scherer, Debt Observatory in Globalisation (ODG). Overview: Flora Sonkin and Stefano Prato, Society for International Development (SID); with support from Matti Kohonen, Christian Aid. -

The Kindertransport

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2014 Apr 29th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM The Power of the People in Influencing the British Government: The Kindertransport Sophia Cantwell St. Mary's Academy Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the Social History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Cantwell, Sophia, "The Power of the People in Influencing the British Government: The Kindertransport" (2014). Young Historians Conference. 15. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2014/oralpres/15 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cantwell 1 Sophia Cantwell Mr. Vannelli PSU MEH The Power of the People in Influencing the British Government: The Kindertransport World War II is known primarily for the Holocaust and the terror Hitler instilled throughout Europe. It is iconic for its disastrous effect on the Jewish culture and its people, but humans all over Europe were harmed and segregated, including homosexuals, people of “insufficient” nationality, and anyone who was perceived as racially inferior. During World War II, in order to escape the horrendous torture of the concentration camps, endangered and persecuted Jews were aided by Britain, who allowed thousands