Holocaust?Series=48246 WEEK 1 Articles and Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Déportés À Auschwitz. Certains Résis- Tion D’Une Centaine, Sont Traqués Et Tent Avec Des Armes

MORT1943 ET RÉSISTANCE BIEN QU’AYANT rarement connu les noms de leurs victimes juives, les nazis entendaient que ni Zivia Lubetkin, ni Richard Glazar, ni Thomas Blatt ne survivent à la « solution finale ». Ils survécurent cependant et, après la Shoah, chacun écrivit un livre sur la Résistance en 1943. Quelque 400 000 Juifs vivaient dans le ghetto de Varsovie surpeuplé, mais les épi- démies, la famine et les déportations à Treblinka – 300 000 personnes entre juillet et septembre 1942 – réduisirent considérablement ce nombre. Estimant que 40 000 Juifs s’y trouvaient encore (le chiffre réel approchait les 55 000), Heinrich Himmler, le chef des SS, ordonna la déportation de 8 000 autres lors de sa visite du ghetto, le 9 janvier 1943. Cependant, sous la direction de Mordekhaï Anielewicz, âgé de 23 ans, le Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB, Organisation juive de combat) lança une résistance armée lorsque les Allemands exécutèrent l’ordre d’Himmler, le 18 janvier. Bien que plus de 5 000 Juifs aient été déportés le 22 janvier, la Résistance juive – elle impliquait aussi bien la recherche de caches et le refus de s’enregistrer que la lutte violente – empêcha de remplir le quota et conduisit les Allemands à mettre fin à l’Aktion. Le répit, cependant, fut de courte durée. En janvier, Zivia Lubetkin participa à la création de l’Organisation juive de com- bat et au soulèvement du ghetto de Varsovie. « Nous combattions avec des gre- nades, des fusils, des barres de fer et des ampoules remplies d’acide sulfurique », rapporte-t-elle dans son livre Aux jours de la destruction et de la révolte. -

Timeline Rudolf Höss

TIMELINE RUDOLF HÖSS (25 Nov 1900 - 16 Apr 1947) Compiled and edited by Campbell M Gold (2010) --()-- Note: Rudolf Höss must not be confused with Rudolf Hess, Hitler's deputy, and one of the first group of Nuremburg defendants. --()-- 25 Nov 1900 - Rudolf Höss born in Baden-Baden, Germany. When he was six or seven years old, the Höss family moved to Mannheim, where Höss was educated. --()-- 1922 - Höss Joins the Nazi Party. --()-- 1934 - Höss joins the SS. --()-- 01 May 1940 - Höss is the first Commandant of Auschwitz where it is estimated that more than a million people were murdered. Jun 1941 - According to Höss' later trial testimony, he was summoned to Berlin for a meeting with Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler "to receive personal orders." Himmler told Höss that Hitler had given the order for the physical extermination of Europe's Jews. Himmler had selected Auschwitz for this purpose, he said, "on account of its easy access by rail and also because the extensive site offered space for measures ensuring isolation." Himmler told Höss that he would be receiving all operational orders from Adolf Eichmann. Himmler described the project as a "secret Reich matter", meaning that "no one was allowed to speak about these matters with any person and that everyone promised upon his life to keep the utmost secrecy." 1941 - After visiting Treblinka extermination camp to study its methods of human extermination, Höss tested and perfected the techniques of mass killing that made Auschwitz the most efficiently murderous instrument of the Final Solution. Later, Höss explained how 10,000 people were exterminated in one 24-hour period: "Technically [it] wasn't so hard – it would not have been hard to exterminate even greater numbers.. -

CHAI News Fall 2018

CENTER FOR HOLOCAUST October 2018 AWARENESS AND INFORMATION (CHAI) CHAI update Tishri-Cheshvan 5779 80 YEARS AFTER KRISTALLNACHT: Remember and Be the Light Thursday, November 8, 2018 • 7—8 pm Fabric of Survival for Educators Temple B’rith Kodesh • 2131 Elmwood Ave Teacher Professional Development Program Kristallnacht, also known as the (Art, ELA, SS) Night of Broken Glass, took place Wednesday, October 3 on November 9-10, 1938. This 4:30—7:00 pm massive pogrom was planned Memorial Art Gallery and carried out 80 years ago to terrorize Jews and destroy Jewish institutions (synagogues, schools, etc.) throughout Germa- ny and Austria. Firefighters were in place at every site but their duty was not to extinguish the fire. They were there only to keep the fire from spreading to adjacent proper- ties not owned by Jews. A depiction of Passover by Esther Historically, Kristallnacht is considered to be the harbinger of the Holocaust. It Nisenthal Krinitz foreshadowed the Nazis’ diabolical plan to exterminate the Jews, a plan that Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Holocaust succeeded in the loss of six million. survivor, uses beautiful and haunt- ing images to record her story when, If the response to Kristallnacht had been different in 1938, could the Holocaust at age 15, the war came to her Pol- have been averted? Eighty years after Kristallnacht, what are the lessons we ish village. She recounts every detail should take away in the context of today’s world? through a series of exquisite fabric collages using the techniques of em- This 80 year commemoration will be a response to these questions in the form broidery, fabric appliqué and stitched of testimony from local Holocaust survivors who lived through Kristallnacht, narrative captioning, exhibited at the as well as their direct descendents. -

Appendix 1: Sample Docum Ents

APPENDIX 1: SAMPLE DOCUMENTS Figure 1.1. Arrest warrant (Haftbefehl) for Georg von Sauberzweig, signed by Morgen. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 129 130 Appendix 1 Figure 1.2. Judgment against Sauberzweig. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde Appendix 1 131 Figure 1.3. Hitler’s rejection of Sauberzweig’s appeal. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 132 Appendix 1 Figure 1.4. Confi rmation of Sauberzweig’s execution. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin- Lichterfelde Appendix 1 133 Figure 1.5. Letter from Morgen to Maria Wachter. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut APPENDIX 2: PHOTOS Figure 2.1. Konrad Morgen 1938. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 134 Appendix 2 135 Figure 2.2. Konrad Morgen in his SS uniform. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 136 Appendix 2 Figure 2.3. Karl Otto Koch. Courtesy of the US National Archives Appendix 2 137 Figure 2.4. Karl and Ilse Koch with their son, at Buchwald. Corbis Images Figure 2.5. Odilo Globocnik 138 Appendix 2 Figure 2.6. Hermann Fegelein. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.7. Ilse Koch. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Appendix 2 139 Figure 2.8. Waldemar Hoven. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.9. Christian Wirth. Courtesy of Yad Vashem 140 Appendix 2 Figure 2.10. Jaroslawa Mirowska. Private collection NOTES Preface 1. The execution of Karl Otto Koch, former commandant of Buchenwald, is well documented. The execution of Hermann Florstedt, former commandant of Majdanek, is disputed by a member of his family (Lindner (1997)). -

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

American Jewish Philanthropy and the Shaping of Holocaust Survivor Narratives in Postwar America (1945 – 1953)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 © Copyright by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) by Rachel Beth Deblinger Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor David N. Myers, Chair The insistence that American Jews did not respond to the Holocaust has long defined the postwar period as one of silence and inaction. In fact, American Jewish communal organizations waged a robust response to the Holocaust that addressed the immediate needs of survivors in the aftermath of the war and collected, translated, and transmitted stories about the Holocaust and its survivors to American Jews. Fundraising materials that employed narratives about Jewish persecution under Nazism reached nearly every Jewish home in America and philanthropic programs aimed at aiding survivors in the postwar period engaged Jews across the politically, culturally, and socially diverse American Jewish landscape. This study examines the fundraising pamphlets, letters, posters, short films, campaign appeals, radio programs, pen-pal letters, and advertisements that make up the material record of this communal response to the Holocaust and, ii in so doing, examines how American Jews came to know stories about Holocaust survivors in the early postwar period. This kind of cultural history expands our understanding of how the Holocaust became part of an American Jewish discourse in the aftermath of the war by revealing that philanthropic efforts produced multiple survivor representations while defining American Jews as saviors of Jewish lives and a Jewish future. -

Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1

1 Proposed Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.4.HE.1.1 Compare and contrast Judaism to other major religions observed around the world, and in the United States and Florida. Grade 5 Standard 1: SS.5.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.5.HE.1.1 Define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of the Jewish people. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Teachers will provide students with an age-appropriate definition of with the Holocaust. Grades 6-8 Standard 1: SS.68.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.68.HE.1.1 Define the Holocaust as the planned and systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Students will define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of Jewish people. Grades 9-12 Standard 1: SS.HE.912.1. Analyze the origins of antisemitism and its use by the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi) regime. SS.912.HE.1.1 Define the terms Shoah and Holocaust. Students will distinguish how the terms are appropriately applied in different contexts. SS.912.HE.1.2 Explain the origins of antisemitism. Students will recognize that the political, social and economic applications of antisemitism led to the organized pogroms against Jewish people. Students will recognize that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are a hoax and utilized as propaganda against Jewish people both in Europe and internationally. -

Jewish Survivors of the Holocaust Residing in the United States

Jewish Survivors of the Holocaust Residing in the United States Estimates & Projections: 2010 - 2030 Ron Miller, Ph. D. Associate Director Berman Institute-North American Jewish Data Bank Pearl Beck, Ph.D. Director, Evaluation Ukeles Associates, Inc. Berna Torr, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Sociology California State University-Fullerton October 23, 2009 CONTENTS AND TABLES Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………….….3 Definitions Data Sources Interview Numbers: NJPS and New York US Nazi Survivor Estimates 2010-2030: Total Number of Survivors and Gender………………6 Table 1: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Total Number of Survivors, by Gender……………………………………………………....7 US Nazi Survivor Estimates 2010-2030: Total Number of Survivors and Age Patterns..………9 Table 2: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Total Number of Survivors, by Age………………………………………………………….10 Poverty: US Nazi Survivors: 2010-2030…………………………….………………………....……11 Table 3: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number of Survivors Below Poverty Thresholds ………………………………………….12 Disability: US Nazi Survivors: 2010-2030…………………………….……………………….....….13 Table 4: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number of Survivors with a Disabling Health Condition ………………………………….14 Severe Disability………………….………………………………………………...…....……15 Table 5: Estimates of Holocaust Survivors, United States, 2001-2030, Number and Percentage of Disabled Survivors Who May Be Severely Disabled ….....17 Disability and Poverty: -

History of the Holocaust

HISTORY OF THE HOLOCAUST: AN OVERVIEW On January 20, 1942, an extraordinary 90-minute meeting took place in a lakeside villa in the wealthy Wannsee district of Berlin. Fifteen high-ranking Nazi party and German government leaders gathered to coordinate logistics for carrying out “the final solution of the Jewish question.”Chairing the meeting was SS Lieutenant General Reinhard Heydrich, head of the powerful Reich Security Main Office, a central police agency that included the Secret State Police (the Gestapo). Heydrich convened the meeting on the basis of a memorandum he had received six months earlier from Adolf Hitler’s deputy, Hermann Göring, confirming his authorization to implement the “Final Solution.” The “Final Solution” was the Nazi regime’s code name for the deliberate, planned mass murder of all European Jews. During the Wannsee meeting German government officials discussed “extermi- nation” without hesitation or qualm. Heydrich calculated that 11 million European Jews from more than 20 countries would be killed under this heinous plan. During the months before the Wannsee Conference, special units made up of SS, the elite guard of the Nazi state, and police personnel, known as Einsatzgruppen, slaughtered Jews in mass shootings on the territory of the Soviet Union that the Germans had occupied. Six weeks before the Wannsee meeting, the Nazis began to murder Jews at Chelmno, an agricultural estate located in that part of Poland annexed to Germany.Here SS and police personnel used sealed vans into which they pumped carbon monoxide gas to suffocate their victims.The Wannsee meeting served to sanction, coordinate, and expand the implementation of the “Final Solution” as state policy. -

Volunteer Translator Pack

TRANSLATION EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES 1. Principles for text, images and audio (a) General principles • Retain the intention, style and distinctive features of the source. • Retain source language names of people, places and organisations; add translations of the latter. • Maintain the characteristics of the source even if these seem difficult or unusual. • Where in doubt make footnotes indicating changes, decisions and queries. • Avoid modern or slang phrases that might be seem anachronistic, with preference for less time-bound figures of speech. • Try to identify and inform The Wiener Library about anything contentious that might be libellous or defamatory. • The Wiener Library is the final arbiter in any disputes of style, translation, usage or presentation. • If the item is a handwritten document, please provide a transcription of the source language as well as a translation into the target language. (a) Text • Use English according to the agreed house style: which is appropriate to its subject matter and as free as possible of redundant or superfluous words, misleading analogies or metaphor and repetitious vocabulary. • Wherever possible use preferred terminology from the Library’s Keyword thesaurus. The Subject and Geographical Keyword thesaurus can be found in this pack. The Institutional thesaurus and Personal Name thesaurus can be provided on request. • Restrict small changes or substitutions to those that help to render the source faithfully in the target language. • Attempt to translate idiomatic expressions so as to retain the colour and intention of the source culture. If this is impossible retain the expression and add translations in a footnote. • Wherever possible do not alter the text structure or sequence. -

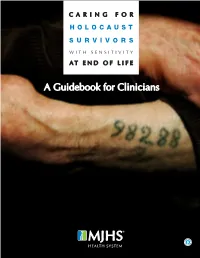

A Guidebook for Clinicians CARING for HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS with SENSITIVITY at END of LIFE

CARING FOR HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS WITH SENSITIVITY AT END OF LIFE A Guidebook for Clinicians CARING FOR HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS WITH SENSITIVITY AT END OF LIFE Dear Colleagues, As clinicians and professional caregivers whose mission it is to manage pain and suffering, we are bound by an oath to “do no harm” and to provide culturally sensitive care. When providing services to Holocaust Survivors and war victims, it is important that we are mindful of our words and actions—particularly because we may be the last generation of caregivers and clinicians who have the honor, as well as the moral obligation, of delivering compassionate health services to Survivors. As one of the largest hospice programs under Jewish auspices in the region, MJHS understands that members of the Jewish community have different levels of observance, and so we tailor our hospice program to meet the individual spiritual and religious practices of each patient. For those who wish to participate, we offer the Halachic Pathway—which is funded by MJHS Foundation and ensures that end-of-life decisions are made in concert with a patient’s rabbinic advisor and adhere to Jewish law and traditions. Our sensitive care to Holocaust Survivors and their families takes into consideration the unique physical, emotional, social and psychological pain and discomfort they experience when facing the end of life. This is one of the many reasons why we seek to share our insights and experiences. This guidebook is for clinicians who have never, or rarely, worked with Holocaust Survivors. It is meant to help users gain a deeper understanding of end-of-life issues that may manifest in the Holocaust Survivor patient, especially ones that can be easily misunderstood or misinterpreted. -

Titel Strafverfahren

HESSISCHES LANDESARCHIV – HESSISCHES HAUPTSTAATSARCHIV ________________________________________________________ Bestand 461: Staatsanwaltschaft bei dem Landgericht Frankfurt am Main Strafverfahren ./. Robert Mulka u.a. (1. Auschwitz-Prozess) Az. 4 Ks 2/63 HHStAW Abt. 461, Nr. 37638/1-456 bearbeitet von Susanne Straßburg Allgemeine Verfahrensangaben Delikt(e) Mord (NSG) Beihilfe zum Mord (NSG) Laufzeit 1958-1997 Justiz-Aktenzeichen 4 Ks 2/63 Sonstige Behördensignaturen 4 Js 444/59 ./. Beyer u.a. (Vorermittlungen) Verfahrensart Strafverfahren Verfahrensangaben Bd. 1-133: Hauptakten (in Bd. 95-127 Hauptverhandlungsprotokolle; in Bd. 128-133 Urteil) Bd. 134: Urteil, gebundene Ausgabe Bd. 135-153: Vollstreckungshefte Bd. 154: Sonderheft Strafvollstreckung Bd. 155-156: Bewährungshefte Bd. 157-165: Gnadenhefte Bd. 166-170: Haftsonderhefte Bd. 171-189: Pflichtverteidigergebühren Bd. 190-220: Kostenhefte Bd. 221-224: Sonderhefte Bd. 225-233: Entschädigungshefte Bd. 234-236: Ladungshefte Bd. 237: Anlage zum Protokoll vom 3.5.1965 Bd. 238-242: Gutachten Bd. 243-267: Handakten Bd. 268: Fahndungsheft Baer Bd. 269: Auslobung Baer Bd. 270: Sonderheft Anzeigen Bd. 271-272: Sonderhefte Nebenkläger Bd. 273-274: Ermittlungsakten betr. Robert Mulka, 4 Js 117/64 Bd. 275-276: Zuschriften Bd. 277-279: Berichtshefte Bd. 280-281: Beiakte betr. Josef Klehr, Gns 3/80, Handakten 1-2 Bd. 282: Sonderheft Höcker Bd. 283: Zustellungsurkunden Bd. 284: Übersetzung der polnischen Anklage vom 28.10.1947 Bd. 285: Fernschreiben Bd. 286; Handakte Auschwitz der OStA I Bd. 287-292: Pressehefte Bd. 293-358: Akten der Zentralen Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen Ludwigsburg Bd. 359-360: Anlageband 12 Bd. 361: Protokolle ./. Dr. Lucas Bd. 362: Kostenheft i.S. Dr. Schatz Bd. 363: Akte der Zentralen Stelle des Landesjustizverwaltungen Ludwigsburg Bd.