Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments.Pdf

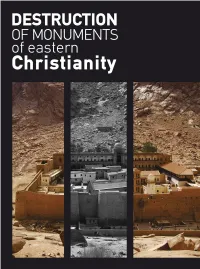

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

Magdalena Sto J an O V a the Cemetery Church of Rožen

MAGDALENA STO J AN O V A THE CEMETERY CHURCH OF ROŽEN MONASTERY Rožen Monastery is situated on a hill between Rožen and Melnik amidst magnificent mountain scenery. Isolated from busy centres and difficult of access—though rich in natural beauty—this position has proved exceptionally favourable for the monastery’s survival up to the present day. Its architecture indicates a relatively early construction date, around the twelfth or thirteenth century1, but the first written source for Rožen Monastery dates only from 15512. Having studied a great number of Greek documents, the architect Alkiviadis Prepis3 has established that the monastery was originally a de pendency with a church dedicated to St George, which was built in the thir teenth century by the Byzantine soldier George Contostephanus Calameas and his wife. According to surviving data from the period up until 1351, in 1309 they presented the dependency to the Georgian Iviron Monastery on Mount Athos, and continued to enrich it4. After this area was conquered by 1. On the basis of the construction and the plan, Assen Vassiliev dates the church to about the twelfth century : A Vassiliev, Ktitorski portreti, Sofia 1960, p. 88. George Trajchev opines that the monastery was built in 1217 (Maitastirite v Makedonija, Sofia 1933, pp. 192- 3). The opinion that the church dates from the fourteenth or fifteenth century is shared by Metropolitan Pimen of Nevrokop ('Roženskija manastir’, Tsarkoven vestnic, 17 (1962) 14) and Professor V. Pandurski ('Tsarcovni starini v Melnik, Ročenskija manastir i Sandanski’, Duhovna cultura, 4 (1964) 16-18). Nichola Mavrodinov suggests an earlier date in: 'Tsarcvi i manastiri v Melnik i Rožen, Godishnik na narodnija musej, vol. -

Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Galliker, Julia, "Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204)" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker, University of Michigan In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 346-373. -

Anna Komnene's Narrative of the War Against The

GRAECO-LATINA BRUNENSIA 19, 2014, 2 MAREK MEŠKO (MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO) ANNA KOMNENE’S NARRATIVE OF THE WAR AGAINST THE SCYTHIANS* The Alexiad by Anna Komnene is well-known. At times it raises controversial issues (e.g. concerning “full” authorship of the Byzantine princess), but all in all it represents a very valuable source of information. In this paper the author strives to examine just how precise and valuable the pieces of information she gives us in connection with the war of her father emperor Alexios Komnenos (1081–1118) against the Scythians (the Pechenegs) are. He also mentions chronological issues which at times are able to “darken” the course of events and render their putting back into the right context difficult. There are many inconsistencies of this type in Anna Komnene’s narrative and for these reasons it is important to reestablish clear chronological order of events. Finally the author presents a concise description of the war against the Pechenegs based on the findings in the previous parts of his paper. Key words: Byzantium, Pechenegs, medieval, nomads, Alexiad, warfare The Alexiad by Anna Komnene1 is well-known to most of the Byzan- tine history scholars. At times it raised controversial issues (e.g. concerning “full” or “partial” authorship of the Byzantine princess),2 but all in all it represents a valuable written source. Regardless of these issues most of the scholars involved agree that it will always remain a unique piece, a special case, of Byzantine literature,3 despite the obvious fact that Anna Komnene’s * This work was supported by the Program of „Employment of Newly Graduated Doc- tors of Science for Scientific Excellence“ (grant number CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0009) co-financed from European Social Fund and the state budget of the Czech Republic. -

Migrating in the Medieval East Roman World, Ca. 600–1204

Chapter 5 Migrating in the Medieval East Roman World, ca. 600–1204 Yannis Stouraitis The movement of groups in the Byzantine world can be distinguished between two basic types: first, movement from outside-in the empire; second, move- ment within the – at any time – current boundaries of the Constantinopolitan emperor’s political authority. This distinction is important insofar as the first type of movement – usually in form of invasion or penetration of foreign peo- ples in imperial lands – was mainly responsible for the extensive rearrange- ment of its geopolitical boundaries within which the second type took place. The disintegration of the empire’s western parts due to the migration of the Germanic peoples in the 5th century was the event that set in motion the con- figuration of the medieval image of the East Roman Empire by establishing the perception in the eastern parts of the Mediterranean that there could be only one Roman community in the world, that within the boundaries of authority of the Roman emperor of Constantinople.1 From that time on, the epicentre of the Roman world shifted toward the East. The geopolitical sphere of the imperial state of Constantinople included the broader areas that were roughly circumscribed by the Italian peninsula in the west, the regions of Mesopotamia and the Caucasus in the east, the North- African shores in the south, and the Danube in the north.2 The Slavic settle- ments in the Balkans and the conquest of the eastern provinces by the Muslims between the late-6th and the late-7th century were the two major develop- ments that caused a further contraction of east Roman political boundaries, thus creating a discrepancy between the latter and the boundaries of the Christian commonwealth that had been established in the east in the course of late antiquity.3 This new geopolitical status quo created new conditions regarding the movement of people and groups within the Empire. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Descending from the Throne: Byzantine Bishops, Ritual and Spaces of Authority Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5q80k7ct Author Rose, Justin Richard Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Descending from the Throne: Byzantine Bishops, Ritual and Spaces of Authority A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Justin Richard Rose December 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Michael Alexander, Co-Chairperson Dr. Sherri Franks Johnson, Co-Chairperson Dr. Sharon E. J. Gerstel Dr. Muhammad Ali Copyright by Justin Richard Rose 2017 The Dissertation of Justin Richard Rose is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson ____________________________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Before all else, I give thanks to Almighty God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Here on earth, I am grateful to my mother, friends and parishioners who have encouraged and supported me throughout this last round of graduate study. And, yes, Mother, this is the last round of graduate study. My experience at the University of California Riverside has been extraordinary. I am especially grateful to Dr. Sherri Franks Johnson for her support and guidance over the last six years. Sherri made my qualifying exam defense a truly positive experience. I am grateful for her continued support even after leaving the UCR faculty for Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge. Thanks to the Religious Studies department for the opportunities I have had during my academic study. -

Ketevan BEZARASHVILI 72B, Iosebidze Street, Apt. 127 Tbilisi, 0160 Georgia Telephone:+995( 32) 37 78 08 E-Mail:[email protected]

Ketevan BEZARASHVILI 72b, Iosebidze Street, Apt. 127 Tbilisi, 0160 Georgia Telephone:+995( 32) 37 78 08 E-mail:[email protected] Curriculum Vitae Education Ph.D. Philology, 2004: Tbilisi State Univcersity Thesis title: "Theory and Practice of Rhetoric and Translation according to the Translations of the Writings of Gregory the Theologian" Ph.D. Philology, 1990: Tbilisi State University. (Candidate) Thesis title: “The Georgian Version of Gregory of Nazianzus’ Poetry”. B.A. (Honors), 1978: Tbilisi State University, Philology. Employment 2002 June: Visiting Researcher at the Catholic University of Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. 1998 June-July: Visiting Researcher at the Catholic University of Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. 1995 February: Visiting Researcher at the Catholic University of Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. 1993-1995: Lecturer, Tbilisi Theological Academy. Lecturer, Independent Institute of Foreign Languages. 1991: Senior Researcher, Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts, Tbilisi. 1990 October-November: Visiting Researcher at the Catholic University of Louvain- la-Neuve, Belgium. 1989 December: Visiting Researcher of “Ivan Dujchev” Research Center for Slavonic-Byzantine Studies at the “Clement Okhridski” University of Sofia, Bulgaria. 1 1986-1991: Researcher, Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts. 1984-1986: Assistant Researcher, Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts. 1983: Lecturer, Tbilisi State University. Assistant, Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts. 1979-1982: Post-graduate student of the Faculty of Old Georgian Literature, Tbilisi State University. Subjects Taught: Byzantine Hymnography Byzantine Epistolography Latin Byzantine-Georgian Literary Interrelations Grants 2004 August - 2007 August: INTAS grant 2000March - 2002 March: INTAS grant 1996 January - 1998 December: INTAS grant Personal Born February 8, 1956, Divorced. A List of Main Publications of K. Bezarashvili for the Last 5 Years: Gelati School (prepared for Pravoslavna% +nciklopedi%). -

The Byzantine Empire.Pdf

1907 4. 29 & 30 BEDFORD STREET, LONDON . BIBLIOTECA AIEZAMANTULUI CULTURAL 66)/ NICOLAE BALCESCU" TEMPLE PRIMERS THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE bY N. JORGA Translated from the French by ALLEN H. POWLES, M.A. All rights reserved AUTHOR'S PREFACE THIs new history of Byzantium, notwithstanding its slender proportions, has been compiled from the original sources. Second-hand materials have only been used to compare the results obtained by the author with those which his pre- decessors have reached. The aim in. view has not been to present one more systematic chronology of Byzantine history, considered as a succession of tragic anecdotes standing out against a permanent background.I have followed the development of Byzantine life in all its length and breadth and wealth, and I have tried to give a series of pictures rather than the customary dry narrative. It may be found possibly that I have given insufficient information on the Slav and Italian neighbours and subjects of the empire.I have thought it my duty to adopt the point of view of the Byzantines themselves and to assign to each nation the place it occupied in the minds of the politicians and thoughtful men of Byzantium.This has been done in such a way as not to prejudicate the explanation of the Byzantine transformations. Much less use than usual has been made of the Oriental sources.These are for the most part late, and inaccuracy is the least of their defects.It is clear that our way of looking v vi AUTHOR'S PREFACE at and appreciatingeventsismuch morethat of the Byzantines than of the Arabs.In the case of these latter it is always necessary to adopt a liberal interpretation, to allow for a rhetoric foreign to our notions, and to correct not merely the explanation, but also the feelings which initiated it.We perpetually come across a superficial civilisation and a completely different race. -

Ljubica Vinulović the Miracle of Latomos: from the Apse of the Hosios David to the Icon from Poganovo

Ljubica Vinulović The Miracle of Latomos: From the Apse of the Hosios David to the Icon from Poganovo. The Migration of the Idea of Salvation Abstract The main preoccupation of this paper will be iconographical analysis of depictions of the Miracle of Latomos, and the way in which this scene migrated from Greece to Bulgaria and Serbia. Firstly, we will discuss the historical background of the Miracle of Latomos and its composition, which is very specific in Byzantine art. Given the fact that it is depicted only three times in Byzantine art, in the mosaic in the apse of the church of Hosios David in Thessaloniki, in the mural painting in the ossuary in Bachkovo monastery in Bulgaria and in the double-sided icon from Poganovo, it has aroused great interest among art historians. The mosaic from Ho- sios David was discovered in 1927, and since then to (up until) the cleaning of the Icon from Poganovo in 1959, the composition of the Miracle of Latomos has had various, interpretations. We will try to explain how this composition has changed its iconography over the centuries and also discuss the question of patronage of the Icon from Poganovo. We will use the iconographic method and try to prove that this composition in all three cases has eschatological character. Key words: Miracle of Latomos, Theodora, Thessaloniki, Hosios David, Ossuary in Bachkovo monastery, Icon from Poganovo, Virgin Kataphyge, John the Theolo- gian, Helena Mrnjavčević The Miracle of Latomos can be traced back to the end of the third century AD, and it is closely related to the city of Thessaloniki and to princess Theodora who was a daughter of August Maximian, co-ruler with the Emperor Diocle- tian, who ruled in Milan during the fourth century.1 This information is prob- ably inaccurate. -

The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology (Bologna, February 15Th, 2019)

The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology (Bologna, February 15th, 2019). Inauguration of the digital exhibition and proceedings of the final meeting of “Byzart - Byzantine Art and Archaeology on Europeana” project Isabella Baldini, Giulia Marsili, Claudia Lamanna, Lucia Maria Orlandi To cite this version: Isabella Baldini, Giulia Marsili, Claudia Lamanna, Lucia Maria Orlandi. The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology (Bologna, February 15th, 2019). Inaugura- tion of the digital exhibition and proceedings of the final meeting of “Byzart - Byzantine Art and Archaeology on Europeana” project. 2019. halshs-02906310 HAL Id: halshs-02906310 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02906310 Submitted on 24 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology Edited by Isabella Baldini Claudia Lamanna Giulia Marsili Lucia Maria Orlandi The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology -

Byzantium in Dialogue with the Mediterranean

Byzantium in Dialogue with the Mediterranean - 978-90-04-39358-5 Downloaded from Brill.com11/09/2020 07:50:13PM via free access <UN> The Medieval Mediterranean peoples, economies and cultures, 400–1500 Managing Editor Frances Andrews (St. Andrews) Editors Tamar Herzig (Tel Aviv) Paul Magdalino (St. Andrews) Larry J. Simon (Western Michigan University) Daniel Lord Smail (Harvard University) Jo Van Steenbergen (Ghent University) Advisory Board David Abulafia (Cambridge) Benjamin Arbel (Tel Aviv) Hugh Kennedy (soas, London) volume 116 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mmed - 978-90-04-39358-5 Downloaded from Brill.com11/09/2020 07:50:13PM via free access <UN> Byzantium in Dialogue with the Mediterranean History and Heritage Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes Mariëtte Verhoeven leiden | boston - 978-90-04-39358-5 Downloaded from Brill.com11/09/2020 07:50:13PM via free access <UN> Cover illustration: Abbasid Caliph al-Mamun sends an envoy to Byzantine Emperor Theophilos, Skyllitzes Matritensis, Unknown, 13th-century author, detail. With kind permission of the Biblioteca Nacional de España. Image editing: Centre for Art Historical Documentation (CKD), Radboud University Nijmegen. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Slootjes, Daniëlle, editor. | Verhoeven, Mariëtte, editor. Title: Byzantium in dialogue with the Mediterranean : history and heritage / edited by Daniëlle Slootjes, Mariëtte Verhoeven. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2019] | Series: The medieval Mediterranean : peoples, economies and cultures, 400-1500, issn 0928-5520; volume 116 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018061267 (print) | lccn 2019001368 (ebook) | isbn 9789004393585 (ebook) | isbn 9789004392595 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Byzantine Empire--Relations--Europe, Western.