Governance of Woodfuel Value Chains in Kenya an Analysis of Policies, Legislative Frameworks and Institutional Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Water Infrastructure Audit of Kitui County

Research Report Research Report Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership A WATER INFRASTRUCTURE AUDIT OF KITUI COUNTY Cliff Nyaga, University of Oxford January 2019 PHOTO CREDIT:PHOTO CLIFF NYAGA/UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Prepared by: Cliff Nyaga, University of Oxford Reviewed by: Mike Thomas, Rural Focus; Eduardo Perez, Global Communities; Karl Linden, University of Colorado Boulder (UCB); and Pranav Chintalapati, UCB. Acknowledgements: The Kitui County Government would like to acknowledge the financial support received from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Further, the Kitui County Government appreciates its longstanding partnership with the University of Oxford and UNICEF Kenya through various collaborating programs, including the DFID-funded REACH Program. The leadership received from Emmanuel Kisangau, Kennedy Mutati, Philip Nzula, Augustus Ndingo, and Hope Sila — all from the County Ministry for Water Agriculture and Livestock Development — throughout the audit exercise is appreciated. The sub-county water officers were instrumental in logistics planning and in providing liaison between the field audit teams, communities, and County Ministries for Agriculture, Water, and Livestock Development and Administration and Coordination. A team of local enumerators led field data collection: Lucy Mweti, Grace Muisyo, Abigael Kyenze, Patrick Mulwa, Lydia Mwikali, Muimi Kivoko, Philip Muthengi, Mary Sammy, Ruth Mwende, Peter Musili, Annah Kavata, James Kimanzi, Purity Maingi, Felix Muthui, and Assumpta Mwikali. The technical advice and guidance received from Professor Rob Hope of the University of Oxford and Dr. Andrew Trevett of UNICEF Kenya throughout the planning, data collection, analysis, and preparation of this report is very much appreciated. Front cover: This Katanu Hand pump was developed in the late 1990s by the Government of Kenya and is the main water source for Nzamba Village in Ikutha Ward, Kitui. -

County Urban Governance Tools

County Urban Governance Tools This map shows various governance and management approaches counties are using in urban areas Mandera P Turkana Marsabit P West Pokot Wajir ish Elgeyo Samburu Marakwet Busia Trans Nzoia P P Isiolo P tax Bungoma LUFs P Busia Kakamega Baringo Kakamega Uasin P Gishu LUFs Nandi Laikipia Siaya tax P P P Vihiga Meru P Kisumu ga P Nakuru P LUFs LUFs Nyandarua Tharaka Garissa Kericho LUFs Nithi LUFs Nyeri Kirinyaga LUFs Homa Bay Nyamira P Kisii P Muranga Bomet Embu Migori LUFs P Kiambu Nairobi P Narok LUFs P LUFs Kitui Machakos Kisii Tana River Nyamira Makueni Lamu Nairobi P LUFs tax P Kajiado KEY County Budget and Economic Forums (CBEFs) They are meant to serve as the primary institution for ensuring public participation in public finances in order to im- Mom- prove accountability and public participation at the county level. basa Baringo County, Bomet County, Bungoma County, Busia County,Embu County, Elgeyo/ Marakwet County, Homabay County, Kajiado County, Kakamega County, Kericho Count, Kiambu County, Kilifi County, Kirin- yaga County, Kisii County, Kisumu County, Kitui County, Kwale County, Laikipia County, Machakos Coun- LUFs ty, Makueni County, Meru County, Mombasa County, Murang’a County, Nairobi County, Nakuru County, Kilifi Nandi County, Nyandarua County, Nyeri County, Samburu County, Siaya County, TaitaTaveta County, Taita Taveta TharakaNithi County, Trans Nzoia County, Uasin Gishu County Youth Empowerment Programs in urban areas In collaboration with the national government, county governments unveiled -

Towards Sustainable Charcoal Production and Trade in Kitui County Phosiso Sola1, Mieke Bourne1, Mary Njenga1, Anthony Kitema2, Siko Ignatius1 and Grace Koech1

CIFOR infobriefs provide concise, accurate, peer- reviewed information on current topics in forest research No. 297, September 2020 DOI: 10.17528/cifor/007721 | cifor.org Towards sustainable charcoal production and trade in Kitui County Phosiso Sola1, Mieke Bourne1, Mary Njenga1, Anthony Kitema2, Siko Ignatius1 and Grace Koech1 Key messages • Woodfuel, particularly charcoal, is an important livelihood source in Kitui County, with consumption largely in urban areas within and beyond the county, where it is still a critical energy source. • While charcoal movement out of the county has been banned since 2018, trade has continued in some form because of inadequate support, guidance and regulation. • While briquette production has been promoted, it has not seen substantial demand. • Because charcoal production has continued, a sustainable charcoal value chain in Kitui County has to be explored, including i) management of woodlands and sustainable harvesting of trees, e.g. through natural regeneration and enrichment planting of trees on degraded private and public lands; ii) promotion of efficient processing and carbonization; and iii) efficient and clean cooking. • Current institutional arrangements for guiding, supporting and controlling the value chain activities and actors can be improved to enhance the sustainability, enforcement, compliance, capacity and competitiveness of local value chains. • World Agroforestry (ICRAF), Adventist Development Relief Agency (ADRA) and partners undertook a number of activities in Kitui County and more widely in Kenya as a whole to generate evidence, knowledge and policy options, and to facilitate engagement for more sustainable woodfuel value chains under the project entitled Governing Multifunctional Landscapes (GML) in sub-Saharan Africa launched in 2018. -

Kitui County

A: Population Projections by Special Groups by- Sub-County and by Sex, 2017 Number Children Household Leadership by Subcounty and Sex KITUI COUNTY GENDER DATA SHEET County, Sub - 3 - 5 years 6 -17 years 200 186 county/Age group 177 Total Male Female Total Male Female 171 180 163 154 INTRODUCTION 160 148 Total County 113,972 58,051 55,922 405,482 206,091 199,391 142 139 141 Kitui County covers an area of 30,515 Km2. It borders Machakos and Makueni counties 140 128 128 Mwingi North 17,880 8,949 8,930 56,681 28,533 28,146 118 120 121 to the west, Tana River County to the east, TaitaTaveta to the south, Embu and 120 106 COUNCIL OF GOVERNORS Mwingi West 11,290 5,798 5,493 43,976 22,414 21,562 TharakaNithi counties to the north. It is located between latitudes 0°10 South and 3°0 100 87 South and longitudes 37°50 East and 39°0 East. Mwingi Central 16,754 8,565 8,189 55,171 28,150 27,022 Number 80 Kitui West 10,245 5,173 5,071 42,139 21,378 20,761 60 A: POPULATION/HOUSEHOLDS 40 Kitui Rural 11,049 5,688 5,361 42,983 21,935 21,049 20 - COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KITUI Kitui Central 12,449 6,381 6,068 48,897 24,623 24,271 A1: Population Projections by sex, 2014-2020 Mwingi Mwingi Mwingi Kitui Kitui Kitui Kitui Kitui Kitui East 14,573 7,280 7,292 48,019 24,555 23,466 Number North West Central West Rural Central East South 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2020 Kitui South 19,733 10,216 9,517 67,615 34,503 33,113 COUNTY GENDER DATA SHEET Boys Girls Total 1,075,866 1,086,599 1,097,687 1,108,981 1,120,394 1,141,592 Source: Kenya Population and Housing Census 2009 -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

Climate Change

ANALYSISANALYSIS ARTICLE 4(1 6), October- December, 2018 ISSN Climate 2394–8558 EISSN 2394–8566 Change Temporal analysis of drought in Mwingi sub- county of Kitui County in Kenya using the standardized precipitation index (SPI) Cassim JZ1, Juma GS2 This study attempts to temporally characterize drought using Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) over Mwingi Sub-County of Kenya. Rainfall data spanning 1961-2011 over the area of study was used to determine SPI values using quantitative techniques in R programming. The SPI values were temporally characterized using series graphs and trend analysis carried out. In order to enhance understanding of vegetative characteristics over the area of study, Vegetation Cover Index data was used to generate 3 month VCI spatial characteristics. Results of this study revealed that Mwingi region has been experiencing increasing mild to moderate drought events with occasional severe cases being reported since 1961. No extreme drought event was recorded during this period. The study noted that the drought events were increasingly varying in intensity during the period of study. The study recommends correlation analysis between all climate variables and SPI values to give direction on how they relate to each other over time. However, no extreme drought event was recorded during this period. The study recommends correlation analysis between the SPI values and all climate variables over the area of study. INTRODUCTION The County is primarily made up of 3 main livelihood zones (LRA, Background of the study 2015) namely: Marginal mixed farming, Mixed farming and Formal Kitui County is situated in the former Eastern Province of Kenya, and employment/Peri-Urban. -

Feeding Infants and Young Children in Kitui County, Kenya

Audience This policy brief is for policy makers, program managers, researchers, and other professionals dealing with nutrition, health, community development, and social and behaviour change and those with an interest in maternal and child health and development in Kitui County. Purpose There is increasing recognition of the need for implementation research that is designed to provide context-specific information and data to inform decisions for planning nutrition and public health interventions. This brief provides evidence for decisions to improve maternal and young child nutrition derived from a systematic landscape analysis in the county. 1. Introduction : This policy brief summarises key results from conducted in selected communities in the four a study designed to identify potential inter- divisions of Kitui Central (Tiva), Lower Yatta ventions to improve nutrition in infants and (Kalunini), Mutomo (Mwamba), and young children in Kitui County, Kenya. The Mutonguni (Musengo). study was commissioned to provide information necessary for the design of Two research approaches were used in Kitui appropriate high-impact nutrition County: interventions in Kitui to improve nutritional Gretel Pelto and Faith Thuita Faith and Pelto Gretel Kenya Brief Policy outcomes at the household level. • Ethnographic research was conducted using the GAIN-initiated Focused The climate of Kitui County varies between Ethnographic Study of Infant and arid and semi-arid, with very erratic and Young Child Feeding Practices (Pelto unreliable rainfall. Most of the area is hot and Infants and Young Children in Kitui County inand Kitui Young Children Infants and Armar-Klemesu 2014). dry. The limited availability of water, coupled with poor soil fertility, presents major challenges for crop cultivation. -

Figure1: the Map of Kenya Showing 47 Counties (Colored) and 295 Sub-Counties (Numbered)

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Additional file 1: The county and sub counties of Kenya Figure1: The map of Kenya showing 47 counties (colored) and 295 sub-counties (numbered). The extents of major lakes and the Indian Ocean are shown in light blue. The names of the counties and sub- counties corresponding to the shown numbers below the maps. List of Counties (bold) and their respective sub county (numbered) as presented in Figure 1 1. Baringo county: Baringo Central [1], Baringo North [2], Baringo South [3], Eldama Ravine [4], Mogotio [5], Tiaty [6] 2. Bomet county: Bomet Central [7], Bomet East [8], Chepalungu [9], Konoin [10], Sotik [11] 3. Bungoma county: Bumula [12], Kabuchai [13], Kanduyi [14], Kimilili [15], Mt Elgon [16], Sirisia [17], Tongaren [18], Webuye East [19], Webuye West [20] 4. Busia county: Budalangi [21], Butula [22], Funyula [23], Matayos [24], Nambale [25], Teso North [26], Teso South [27] 5. Elgeyo Marakwet county: Keiyo North [28], Keiyo South [29], Marakwet East [30], Marakwet West [31] 6. Embu county: Manyatta [32], Mbeere North [33], Mbeere South [34], Runyenjes [35] Macharia PM, et al. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003014. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health 7. Garissa: Balambala [36], Dadaab [37], Dujis [38], Fafi [39], Ijara [40], Lagdera [41] 8. -

Kitui County EWS Bulletin

National Drought Management Authority KITUI COUNTY DROUGHT EARLY WARNING BULLETIN FOR APRIL 2021 Early Warning Phase Classification APRIL EW PHASE LIVELIHOOD ZONE EW TRENDS PHASE Marginal Mixed Farming Alert Worsening Mixed Farming Normal Worsening County Alert Worsening Drought Situation & EW Phase Classification Biophysical Indicators Biophysical Indicators Value Normal ranges ▪ The county experienced depressed rainfall with Rainfall (% of normal) 51-75 80-120 late onset in the first dekad of April. VCI-3 month 34.29 35-50 ▪ The vegetation greenness was below normal. VCI-3 month forecast June-03 50 35-50 ▪ VCI forecast indicates normal to above normal Forage Condition Good to Good to fair poor vegetation greenness. Socio-Economic Indicators (Impact Indicators) Production indicators Value Normal ranges Production Indicators Maize Crop Condition Poor Good ▪ Early planted crops had germinated and were Livestock Body Condition Fair to poor Good to fair in poor condition due to moisture stress. Milk Production (in litres) 1.4 ≥ 1.3 ▪ Livestock body condition was fair to poor with Livestock Migration Pattern Normal Normal normal cases of livestock migration and deaths. Livestock Deaths (from ▪ Confirmed cases of FMD, Trypanomiasis and Drought) No death No death Helmithiasis diseases were reported. Access Indicators Value Normal ranges Terms of Trade (ToT) 133 ≥ 105 ▪ Milk production was within normal range. Milk Consumption (in litres) 1.1 ≥ 0.9 Access Indicators Return Distance to Water 4.0 ≤ 6.1 ▪ Terms of trade were favourable. Sources (in km) ▪ Milk consumption was within normal range. Cost of Water at Source (20 2-5 ≤ 5Ksh ▪ Water distances were within normal range. litres Jerry can) ▪ The cost of water at source was normal. -

County Government of Kitui

COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KITUI COUNTY ASSEMBLY SECOND ASSEMBLY – (SECOND SESSION) ______________________________________________ COMMITTEEE ON TRADE, INDUSTRY, I.C.T AND CO-OPERATIVES __________________________________________ REPORT ON THE BENCHMARKING TRIP TO VARIOUS CO- OPERATIVE SOCIETIES IN MURANGA, KIAMBU, AND NYERI COUNTIES CLERK’S CHAMBERS, JUNE, 2018 COUNTY ASSEMBLY BUILDINGS, KITUI, KENYA 1 PREFACE Hon. Speaker, On behalf of the members of the Trade, Industry, ICT and Co-operatives Committee, and pursuant to the provisions of standing order no.179 (6) and 190(5), I beg to present before the house, the committee’s report on the benchmarking trip to various co-operative societies in Muranga, Kiambu, Nyeri and Meru Counties. The visit was carried out from the 23rd to 27th January 2018 the purpose of which was to benchmark on the best practices of running and managing co-operative societies, value addition of products, and generally share ideas on the viable practices that are likely to bring development and uplift economic status of members. Kitui County through the County Ministry of Trade, Industry and Co-operatives is on the forefront of facilitating cooperative societies to play an important role in addressing the challenges of low productivity, inappropriate land use systems, poor marketing systems, limited access to credit by farmers and small businesses, and low value-addition to agricultural commodities and other services. It is worthy to note that some of the major benefits that accrue to Kenyans through cooperative societies include creation of employment, settlement of the people, and generation of income and acquisition of property. In addition to the more conventional functions of marketing and production, cooperatives increasingly serve as agents of social and economic change, and are therefore vibrant civil society actors. -

Usaid Kenya Afya Halisi Quarterly Progress Report

USAID KENYA AFYA HALISI QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT Young Mothers Dialogue session at Katito Health Centre, Nyakach Sub-County Photo 1 CME on use of Partograph and EmONC Signal functions at St. Josephs Mission Rapogi in Uriri Sub-county, Migori County. APRIL 2019 OCTOBER 2017 This publication was produced byfor Afyareview Halisi by thefor reviewUnited byStates the AgencyUnited Statesfor International Agency for Development. International ItDevelopment. was prepared by Dr. Gathari Ndirangu and the team of MCSP Kenya Technical Advisors USAID KENYA AFYA HALISI PROJECT FY 2019 Q2 PROGRESS REPORT January 1 – March 31, 2019 Award No: AID-615-A-17-00004 Prepared for Lillian Mutea United States Agency for International Development/Kenya C/O American Embassy United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 629, Village Market 00621 Nairobi, Kenya Prepared by Jhpiego Jhpiego offices, 2nd Floor, Arlington Block, 14 Riverside, off Riverside Drive, P.O Box 66119-00800 Nairobi Office tel: +254 732 134 000 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. I. AFYA HALISI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................... 1 II. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS (Qualitative Impact) ............................................................. 7 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (Quantitative Impact) ...................................................... 60 IV. CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ............................................................ -

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

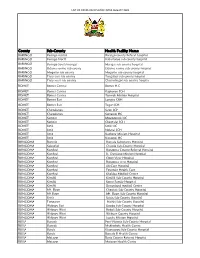

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye