The Regionalisation of the South Sudanese Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secession of South Sudan: a Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Political Science Student Work Political Science 2012 The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition Christian Knox College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/polsci_students Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Knox, Christian, "The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition" (2012). Political Science Student Work. 1. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/polsci_students/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition An Honors Thesis College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for All College Honors and Distinction in the Department of Political Science by Christian Knox May, 2012 Knox 2 ABSTRACT: This thesis focuses on the recent secession of South Sudan. The primary research questions include an examination of whether or not South Sudan’s 2011 secession signaled a break from the O.A.U.’s traditional doctrines of African stability and noninterference. Additionally, this thesis asks: why did the United States and the international community at large confer recognition to South Sudan immediately upon its independence? Theoretical models are used to examine the independent variables of African stability, ethnic secessionism, and geopolitics on the dependent variables of international recognition and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. -

Human Resources for Health Challenges in Fragile States: Evidence from Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe

Human Resources for Health Challenges in Fragile States: Evidence from Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe James MacKinnon and Barbara MacLaren The North-South Institute August 2012 Context Health indicators in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS) paint a dire picture for their residents, with no quick-fix solution easily identified. Greater financial and human resources are needed to fill gaps, but training new nurses, doctors, midwives and allied health professionals takes time that many fragile states simply cannot afford. Emigration of health professionals from FCAS can create a negative feedback loop for health outcomes and highlights the important challenges surrounding sustainable human resources for health (HRH) in fragile states. To shed light on one aspect of the dynamics of creating robust health systems in FCAS, this report looks at the severity of the health workforce crisis in three FCAS: Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe. The objectives of this report are to: • Identify key health and human resource indicators in the three countries and situate them in the regional context; • Identify key training issues with regard to human resources for health; and • Identify policies in human resources for health and determine their implementation status. This research will inform a scoping study on diaspora engagement in fragile states being developed in collaboration with the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The study will examine the impact of African diaspora health professionals in short and medium-term placements and test the skills circulation theory in fragile states. This project will build on past North-South Institute work on the implications of the brain drain on the status of health in Southern Africa, as well as numerous policy briefs on gender equity, migration and trade. -

Kareem Olawale Bestoyin*

Historia Actual Online, 46 (2), 2018: 43-57 ISSN: 1696-2060 OIL, POLITICS AND CONFLICTS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NIGERIA AND SOUTH SUDAN Kareem Olawale Bestoyin* *University of Lagos, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 3 septiembre 2017 /Revisado: 28 septiembre 2017 /Aceptado: 12 diciembre 2017 /Publicado: 15 junio 2018 Resumen: A lo largo de los años, el Áfica sub- experiencing endemic conflicts whose conse- sahariana se ha convertido en sinónimo de con- quences have been under development and flictos. De todas las causas conocidas de conflic- abject poverty. In both countries, oil and poli- tos en África, la obtención de abundantes re- tics seem to be the driving force of most of cursos parece ser el más prominente y letal. these conflicts. This paper uses secondary data Nigeria y Sudán del Sur son algunos de los mu- and qualitative methodology to appraise how chos países ricos en recursos en el África sub- the struggle for the hegemony of oil resources sahariana que han experimentado conflictos shapes and reshapes the trajectories of con- endémicos cuyas consecuencias han sido el flicts in both countries. Hence this paper de- subdesarrollo y la miserable pobreza. En ambos ploys structural functionalism as the framework países, el petróleo y las políticas parecen ser el of analysis. It infers that until the structures of hilo conductor de la mayoría de estos conflic- governance are strengthened enough to tackle tos. Este artículo utiliza metodología de análisis the developmental needs of the citizenry, nei- de datos secundarios y cualitativos para evaluar ther the amnesty programme adopted by the cómo la pugna por la hegemonía de los recur- Nigerian government nor peace agreements sos energéticos moldea las trayectorias de los adopted by the government of South Sudan can conflictos en ambos países. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

The Influence of South Sudan's Independence on the Nile Basin's Water Politics

A New Stalemate: Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 The Influence of South Sudan’s Master thesis in Sustainable Development Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Jon Roozenbeek Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 15 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2014. E, 15 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 Master thesis in Sustainable Development A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Supervisor: Ashok Swain Evaluator: Eva Friman Master thesis in Sustainable Development Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Research Aim .................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Methods ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. Case Selection ................................................................................................................. 7 1.5. Limitations ..................................................................................................................... -

Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Zachary Mondesire 2018 © Copyright by Zachary Mondesire 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba By Zachary Mondesire Master of Art in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Hannah C. Appel, Chair The world’s newest state, South Sudan, became independent in July 2011. In 2013, after the outbreak of the still-ongoing South Sudanese civil war, the UNHCR declared a refugee crisis and continues to document the displacement of millions of South Sudanese citizens. In 2016, Crazy Fox, a popular South Sudanese musician, released a song entitled “Ana Gaid/I am staying.” His song compels us to pay attention to those in South Sudan who have chosen to stay, or to return and still other African regionals from neighboring countries to arrive. The goal of this thesis is to explore the “Crown Lodge,” a hotel in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, as one such site of arrival, return, and staying put. Paying ethnographic attention to site enables us to think through forms of spatial belonging in and around the hotel that attached racial meaning to national origin and regional identity. ii The thesis of Zachary C. P. Mondesire is approved. Jemima Pierre Aomar Boum Hannah C. Appel, Committee Chair University -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

The Charcoal Grey Market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan (2021)

COMMODITY REPORT BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan SIMONE HAYSOM I MICHAEL McLAGGAN JULIUS KAKA I LUCY MODI I KEN OPALA MARCH 2021 BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan ww Simone Haysom I Michael McLaggan Julius Kaka I Lucy Modi I Ken Opala March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank everyone who gave their time to be interviewed for this study. They would like to extend particular thanks to Dr Catherine Nabukalu, at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bryan Adkins, at UNEP, for playing an invaluable role in correcting our misperceptions and deepening our analysis. We would also like to thank Nhial Tiitmamer, at the Sudd Institute, for providing us with additional interviews and information from South Sudan at short notice. Finally, we thank Alex Goodwin for excel- lent editing. Interviews were conducted in South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya between February 2020 and November 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Simone Haysom is a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), with expertise in urban development, corruption and organized crime, and over a decade of experience conducting qualitative fieldwork in challenging environments. She is currently an associate of the Oceanic Humanities for the Global South research project based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Ken Opala is the GI-TOC analyst for Kenya. He previously worked at Nation Media Group as deputy investigative editor and as editor-in-chief at the Nairobi Law Monthly. He has won several journalistic awards in his career. -

Reintegration of Child Soldiers Through Peace Education in Sierra Leone: a Potential Model for South Sudan?

COMILLAS PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Degree in International Relations Final Degree Project Reintegration of Child Soldiers Through Peace Education in Sierra Leone: A Potential Model for South Sudan? Student: Pilar Roig Minguell Director: Heike Clara Pintor Pirzkall Madrid, April 2019 Acknowledgements To my director and teacher Heike, for her patience, availability, expertise and ideas that have helped me engage with this work. To my family and friends, for supporting me unconditionally throughout my degree, for their kindness and honesty when I most needed it. To Mr. Rehm, my English teacher at Kents Hill School, for recommending me pieces of literature like A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, which opened my eyes to different realities and have motivated me to work to make a difference in the world. i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... i Table of Contents ............................................................................................................. ii List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Aim and motivation ................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Theoretical background and literature -

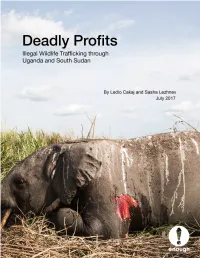

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES and OPPORTUNITIES for ENGAGEMENT by Jacqueline Wilson

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENGAGEMENT By Jacqueline Wilson NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 Making Peace Possible NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 ABOUT THE REPORT This report showcases religious actors and institutions in South Sudan, highlights chal- lenges impeding their peace work, and provides recommendations for policymakers RELIGION and practitioners to better engage with religious actors for peace in South Sudan. The report was sponsored by the Religion and Inclusive Societies program at USIP. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jacqueline Wilson has worked on Sudan and South Sudan since 2002, as a military reserv- ist supporting the Comprehensive Peace Agreement process, as a peacebuilding trainer and practitioner for the US Institute of Peace from 2004 to 2015, and as a Georgetown University scholar. She thanks USIP’s Africa and Religion and Inclusive Societies teams, Matthew Pritchard, Palwasha Kakar, and Ann Wainscott for their support on this project. Cover photo: South Sudanese gather following Christmas services at Kator Cathedral in Juba. (Photo by Benedicte Desrus/Alamy Stock Photo) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2019 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 148. First published 2019.