Transcript of Oral History Interview with Frank Kroncke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libro EVERYTHING COUNTS Final

Everything Counts! Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America 1 Everything Counts! The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or IDRC Canada concerning that legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the elimination of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or IDRC Canada. The publication of this book was made possible through the financial support provided by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to the project: “Asumiendo el reto de la equidad de género en la gestión ambiental en América Latina”. Pubished by: IUCN-ORMA, The World Conservation Union Regional Office for Mesoamerica, in collaboration with: Rights Reserve: © 2004 The World Conservation Union Reproduction of this text is permitted for non-commercial and educational purposes only. All rights are reserved. Reproduction for sale or any other commercial purposes is strictly prohibited, without written permission from the authors. Quotation: 333.721.4 I -92e IUCN. ORMA. Social Thematic Area Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America / Comp. por IUCN-ORMA. Social Thematic Area; Edit. por Linda Berrón Sañudo; Tr. por Ana Baldioceda Castro. – San José, C.R.: World Conservation Union, IUCN, 2004. 203 p.; 28 cm. ISBN 9968-743- 87 - 9 Título en español: ¡Todo Cuenta! El valor de las iniciativas de conservación con enfoque de género en Latinoamérica 1.Medioambiente. -

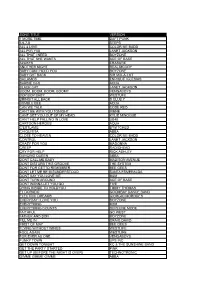

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

POP Vol 1 Song List

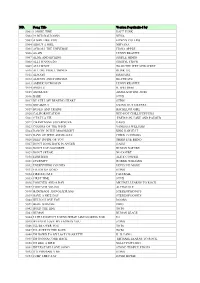

NO. Song Title Version Popularized by 5001 1 MORE TIME DAFT FUNK 5002 99 RED BALLOONS NENA 5003 A GIRL LIKE YOU EDWYN COLLINS 5004 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA 5005 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE FIONA APPLE 5006 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ 5007 ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS 5008 ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW 5009 ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 5010 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 5011 ALWAYS ERASURE 5012 ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEATWAVE 5013 AMERICAN WOMAN LENNY KRAVITZ 5014 ANGELS R. WILLIMAS 5015 ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS 5016 BABE STYX 5017 BE STILL MY BEATING HEART STING 5018 BREAKOUT SWING OUT SISTERS 5019 BUSES AND TRAINS BACHELOR GIRL 5020 CALIFORNICATION RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS 5021 C’EST LA VIE EMERSON, LAKE AND PALMER 5022 CHAMPAGNE SUPERNOVA OASIS 5023 COLORS OF THE WIND VANESSA WILLIAMS 5024 DANCIN’ IN THE MOONLIGHT KING HARVEST 5025 DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES CHRIS CONNORS 5026 DEEP INSIDE OF YOU THIRD EYE BLIND 5027 DON’T LOOK BACK IN ANGER OASIS 5028 DON’T SAY GOODBYE HUMAN NATURE 5029 DON’T SPEAK NO DOUBT 5030 EIGHTEEN ALICE COOPER 5031 ETERNITY ROBBIE WILLIAMS 5032 EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE 5033 FIELDS OF GOLD STING 5034 FIRE ESCAPE FASTBALL 5035 FIRST TIME STYX 5036 FOREVER AND A DAY MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK 5037 FOREVER YOUNG ALPHAVILLE 5038 HANDBAGS AND GLADRAGS STEREOPHONICS 5039 HAVE A NICE DAY STEREOPHONICS 5040 HELLO I LOVE YOU DOORS 5041 HERE WITH ME DIDO 5042 HOLD THE LINE TOTO 5043 HUMAN HUMAN LEAGE 5044 I STILL HAVEN’T FOUND WHAT I AM LOOKING FOR U2 5045 IF I EVER LOSE MY FAITH IN YOU STING 5046 I’LL BE OVER YOU TOTO 5047 I’LL SUPPLY THE LOVE TOTO 5048 I’M DOWN TO MY LAST CIGARETTE K. -

COLLECTED the Alan Wilder/Depeche Mode Historic Equipment, Vinyl & Memorabilia Auction

auction.recoil.co.uk omegaauctions.co.uk COLLECTED THE ALAN WILDER/DEPECHE MODE HISTORIC EQUIPMENT, VINYL & MEMORABILIA AUCTION Saturday 3rd September 2011 COLLECTED THE ALAN WILDER/DEPECHE MODE HISTORIC EQUIPMENT, VINYL & MEMORABILIA AUCTION Saturday 3rd September 2011 at 3.00pm Zion Arts Centre, 335 Stretford Road, Hulme, Manchester, M15 5ZA ON VIEW Friday 2nd September 11.00am - 8.00pm Saturday 3rd September 10.00am - 2.45pm Catalogue £5.00 Omega Auctions Telephone: +44 161 865 0838 Email: [email protected] www.omegaauctions.co.uk HISTORY - ALAN WILDER FOREWORD After classical training from an early age, Alan Wild- “Since those heady DM years, I have concentrated fully on my once side project Recoil (which originated in er’s career in music began at the age of 16 when he 1986). The most significant work has evolved since 1996. Free from former commitments, I began operating secured the position of studio assistant at DJM Studi- from my own studio, ‘The Thin Line’, and at my own pace, gradually piecing together what would become the os in London’s West End. Following 3 years of moder- ‘Unsound Methods’, ‘Liquid’ and ‘subHuman’ albums. Over the course of the last 12 years I have been ably ac- ate success in a variety of different bands, he joined companied by Paul Kendall who brings his idiosyncratic view to the whole procedure. Depeche Mode in 1981 after replying to an advert in Melody Maker. The recent ‘Selected’ collection is made up of my personal favourites, remastered and edited together into what I consider a cohesive and total listening experience. -

Depeche Mode Everything Counts Mp3, Flac, Wma

Depeche Mode Everything Counts mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Everything Counts Country: Europe Released: 2004 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1670 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1213 mb WMA version RAR size: 1984 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 708 Other Formats: TTA DTS ADX MP4 WAV MP1 MP4 Tracklist 1 Everything Counts 3:58 2 Work Hard 4:22 3 Everything Counts (In Larger Amounts) 7:20 4 Work Hard (East End Remix) 6:59 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mute Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Mute Records Ltd. Published By – Sonet Publishing Glass Mastered At – EMI Uden Pressed By – EMI Uden Recorded At – The Garden Mixed At – Hansa Mischraum Credits Artwork [Origiinal Sleeve Illustration] – Ian Wright Design – T+CP Associates* Engineer – Gareth Jones Producer – Daniel Miller, Depeche Mode Written-By – A Wilder* (tracks: 2, 4), M.L. Gore* Notes Tracks 1, 3 published by Grabbing Hands / Sonet Tracks 2, 4 published by Grabbing Hands / Sonet-Sonet Recorded at The Garden Studios, London. Tracks 1, 3 mixed at Hansa Mischraum, Berlin. ℗ 1983 Mute Records (sleeve) ℗ 1983 Mute Records Limited (disc) © 1991 Mute Records Limited Made in the EU Printed in E.U. Everything Counts (Bong 3) released August 11th 1983 From the album Construction Time Again Packaging: j-card case. UK/Europe CD releases with identical catalogue number: 1. Glass mastered at DADC Austria 2. Glass mastered at Nimbus 3. Glass mastered at EMI Uden, only Mute logo on sleeve & disc 4. Glass mastered at and pressed by EMI Uden, Mute / Virgin / Labels logos on sleeve (this one) 5. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

Depeche Mode Friends, P

HALO 29 Dokument nepredstavuje konečnou podobou časopisu. Obsahuje iba texty, použité v HALO 29. Halo 29 Hello Friends, Jsme tu opět v novém roce 2002. Můžeme Vám sdělit, že v tuto chvíli se dozajista stříhá nové video album, které vyjde v průběhu tohoto roku. Toto album si budete možná moct připomenout ještě na pár přidaných koncertech. V novém čísle Vám přinášíme informace o novém singlu Goodnight Lovers. Pokud jste pozorní TV diváci, již jste mohli zaregistrovat nový klip. Uveřejňujeme také poslední text z alba Exciter. Přečíst si můžete také pár recenzí na koncerty z Exciter Tour. Obměnili jsme pro Vás sběratelské předměty v FC Shopu. Příjemné čtení a see you next time DMF Adresa DMF: Depeche Mode Friends, P. O. BOX 239, 160 41 Praha 6, tel. (+420) 603/420 937, 0608/208 342 http://www.dmfriends-silence.cz, http://www.depechemode.cz, www.depechemode.sk e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Pobočky DMF: DMF Slovensko: DM FC Friends, Kozmonautov 26/28, 036 01 Martin, Slovensko 0903/531 015, 0903/547 978 http://www.dmfdepechemode.host.sk e-mail: [email protected] DM News nominováni jsou na hudební cenu: Category #10 - Best Dance Recording 1. "One More Time" - Daft Punk 2. "I Feel Loved" - Depeche Mode 3. "Out Of Nowhere" - Gloria Estefan 4. "All For You" - Janet Jackson 5. "Angel" - Lionel Ritchie Category #86 - Best Remixed Recording, Non-Classical 1. "Heard It All Before" (E-Smoove House Filter Mix) - E-Smoove (remixer: Sunshine Anderson) 2. "I Feel Loved" - Depeche Mode (remixer: Danny Tenaglia) 3. "Thank You" (Deep Dish Vocal Remix) - Dido (remixer: Deep Dish) 4. -

Dave Gahan, Magnétisent Toujours Les Stades

GAB HS.indd 1 12/06/18 11:41 ÉDITO T ête d’affiche de nombreux festivals à travers l’Europe et en particulier en France, Depeche Mode va cet été encore rassembler les foules. Pourtant, à ses tout débuts, en 1980, rien ne laissait présager que ce quatuor de jeunes freluquets dominerait encore le monde de la pop en 2018. Moqué pour son look, méprisé pour sa musique sans guitare, Depeche Mode a néanmoins rapidement réussi à populariser une pop synthétique irrésistible, dansante et cérébrale à la fois, faisant résonner des textes désenchantés sur les dancefloors du monde entier – et ouvrant la voie à toute une vague d’artistes new-wave et synthpop. Ce qui fascine surtout, c’est que Depeche Mode, contrairement à de nombreux groupes ayant aussi connu le succès dans les années 1980, a su perdurer. Malgré des épreuves et des tourments personnels, le groupe a traversé les époques en restant au sommet. Il a fait mûrir sa musique en revenant aux guitares – sans jamais renier l’apport des claviers –, il ne s’est jamais laissé submerger par les modes successives – techno, house, electro… Au contraire, Depeche Mode a su renouveler sa pop en y incorporant les sons du moment, en s’entourant de remixeurs et producteurs pointus et dans l’air du temps. Le groupe n’a cessé de sortir des albums solides et cohérents qui, sans prendre une ride, se sont même bonifiés avec le temps. Signe de sa crédibilité, Depeche Mode a d’ailleurs toujours servi de référent et d’influence à ses contemporains, cité autant par les indus Nine Inch Nails que par le psychédélique Jonathan Wilson. -

Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy the Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel of a Gun

SINGLE DE DEPECHE MODE EVERYTHING COUNTS WRONG ENJOY THE SILENCE ITS NO GOOD I FEEL YOU PERSONAL JESUS STRANGELOVE BARREL OF A GUN PDF-33SDDMECWETSINGIFYPJSBOAG16 | Page: 133 File Size 5,909 KB | 10 Oct, 2020 PDF File: Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You 1/3 Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun - PDF-33SDDMECWETSINGIFYPJSBOAG16 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Brief Description Main Topic Technical Note Appendix Glossary PDF File: Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You 2/3 Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun - PDF-33SDDMECWETSINGIFYPJSBOAG16 Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun e-Book Name : Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun - Read Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun PDF on your Android, iPhone, iPad or PC directly, the following PDF file is submitted in 10 Oct, 2020, Ebook ID PDF-33SDDMECWETSINGIFYPJSBOAG16. Download full version PDF for Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun using the link below: Download: SINGLE DE DEPECHE MODE EVERYTHING COUNTS WRONG ENJOY THE SILENCE ITS NO GOOD I FEEL YOU PERSONAL JESUS STRANGELOVE BARREL OF A GUN PDF The writers of Single De Depeche Mode Everything Counts Wrong Enjoy The Silence Its No Good I Feel You Personal Jesus Strangelove Barrel Of A Gun have made all reasonable attempts to offer latest and precise information and facts for the readers of this publication. -

The Scars That Have Shaped Me: How God Meets Us in Suffering

“Vaneetha writes with creativity, biblical faithfulness, com- pelling style, and an experiential authenticity that draws other sufferers in. Here you will find both a tested life and a love for the sovereignty of a good and gracious God.” —JOHN PIPER, author of Desiring God; founder and teacher, desiringGod.org “The Scars That Have Shaped Me will make you weep and rejoice not just because it brims with authenticity and integrity, but because every page points you to the rest that is found in entrusting your life to one who is in complete control and is righteous, powerful, wise, and good in every way.” —PAUL TRIPP, pastor, author, international conference speaker “I could not put this book down, except to wipe my tears. Reading Vaneetha’s testimony of God’s kindness to her in pain was exactly what I needed; no doubt, many others will feel the same. The Scars That Have Shaped Me has helped me process my own grief and loss, and given me renewed hope to care for those in my life who suffer in various ways. Reveling in the sovereign grace of God in your pain will bolster your faith like nothing this world can offer, and Vaneetha knows how to lead you to this living water.” —GLORIA FURMAN, author of Missional Motherhood and Alive in Him “When we are suffering significantly, it’s hard to receive truth from those who haven’t been there. But Vaneetha Risner’s credibility makes us willing to lean in and listen. Her writing is built on her experience of deep pain, and in the midst of that her rugged determination to hold on to Christ.” —NANCY GUTHRIE, author of Hearing Jesus Speak into Your Sorrow “I have often wondered how Vaneetha Risner endures suffering with such amazing joy, grace, and perseverance. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay Dizm Bartender She Got It (Movie Version) King & I 2 Unlimited Getting To Know You No Limit *Nsync 20 Fingers Bye Bye Bye Short #### Man Girlfriend 21St Century Girls God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You 21St Century Girls I Drive Myself Crazy 3 Doors Down I Want You Back Away From The Sun Ill Never Stop Be Like That Its Gonna Be Me Citizen Soldier Pop Duck & Run Somewhere Someday Every Time You Go Tearin Up My Heart Here By Me This I Promise You Here Without You *Nsync & Gloria Estefan Its Not My Time Music Of My Heart (Duet) Kryptonite 10 Years Let Me Be Myself Beautiful Let Me Go 10,000 Maniacs Live For Today More Than This Loser These Are The Days The Road Im On Trouble Me When Im Gone 101 Dalmations When Youre Young Cruella De Vil 311 10Cc All Mixed Up Dreadlock Holiday Down Im Mandy Hey You Im Not In Love Love Song Rubber Bullets 35L The Things We Do For Love Take It Easy 112 38 Special Dance With Me Back Where You Belong Peaches & Cream Caught Up In You 12 Gauge Hold On Loosely Dunkie Butt Rockin Into The Night 12 Stones Second Chance We Are One Teacher Teacher 1910 Fruitgum Co Wild Eyed Southern Boys Simon Says 3Lw 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More Baby Ima Do Right 1 2 3 Red Light 3OH!3 2 Evisa Dont Trust Me Ooh La La La Double Vision 2 Live Crew StarStrukk Me So Horny 3OH!3 & Ke$ha We Want Some P###Y My First Kiss (Background Female) 2 Pac My First Kiss (Duet) California Love 3OH!3 & Neon Hitch Changes Follow Me Down (Duet) Until The End Of Time 3T 2 Pistols -

Library 217 Songs, 19.3 Hours, 1.05 GB

Library 217 songs, 19.3 hours, 1.05 GB Song Name Time Album Artist (Set Me Free) Remotivate Me 4:13 Master and Servant Depeche Mode (Set Me Free) Remotivate Me (Release) 8:49 Master and Servant Depeche Mode A Question of Lust 4:29 A Question of Lust Depeche Mode A Question of Lust 4:30 Singles 86>98 Depeche Mode A Question of Lust (Minimal) 6:47 A Question of Lust Depeche Mode A Question of Time 4:00 Singles 86>98 Depeche Mode A Question of Time (Extended) 6:39 A Question of Time Depeche Mode A Question of Time (New Town/Live) 11:08 A Question of Time Depeche Mode A Question of Time (Remix) 4:05 A Question of Time Depeche Mode Any Second Now 3:09 Just Can't Get Enough Depeche Mode Any Second Now (Altered) 5:42 Just Can't Get Enough Depeche Mode Barrel of a Gun 5:35 Ultra Depeche Mode Barrel of a Gun 5:26 Singles 86>98 Depeche Mode Behind the Wheel 4:02 Singles 86>98 Depeche Mode Behind the Wheel/Route 66 (Mega-… 4:22 Just Say Yo Depeche Mode Black Celebration (Black Tulip) 6:34 A Question of Time Depeche Mode Black Celebration (Live) 6:05 A Question of Time Depeche Mode Black Day 2:37 Stripped Depeche Mode Blasphemous Rumours 6:23 Blasphemous Rumours Depeche Mode Blue Dress 5:41 Violator Depeche Mode Bottom Line, The 4:26 Ultra Depeche Mode Breathe 5:17 Exciter Depeche Mode Breathing in Fumes 6:06 Stripped Depeche Mode But Not Tonight 4:17 Stripped Depeche Mode But Not Tonight (Extended) 5:14 Stripped Depeche Mode Christmas Island 4:51 A Question of Lust Depeche Mode Christmas Island (Extended) 5:39 A Question of Lust Depeche Mode Clean