NIBAFASHA SPES M.A DISSERTATION 2013.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN): Burundi

U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) Burundi Sommaire / Contents BURUNDI HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT No. 4...............................................................5 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 26 July 1996 (96.7.26)..................................................9 Burundi-Canada: Canada Supports Arusha Declaration 96.8.8..............................................................11 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 14 August 1996 96.8.14..............................................13 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 15 August 1996 96.8.15..............................................15 Burundi: Statement by the US Catholic Conference and CRS 96.8.14...................................................17 Burundi: Regional Foreign Ministers Meeting Press Release 96.8.16....................................................19 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 16 August 1996 96.8.16..............................................21 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 20 August 1996 96.8.20..............................................23 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 21 August 1996 96.08.21.............................................25 Burundi: Notes from Burundi Policy Forum meeting 96.8.23..............................................................27 Burundi: IRIN Summary of Main Events for 23 August 1996 96.08.23................................................30 Burundi: Amnesty International News Service 96.8.23.......................................................................32 -

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin N° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin n° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011 Map of emergency assistance needs in agriculture ► Increase of theft of crops and in households is for season 2012A N concerning as it is likely to bear a negative impact on food stocks and reserves from Season 2011B crops; Bugabira Busoni Giteranyi ► Whereas normally it is dry season, torrential rains with Kirundo Bwambarangwe Ntega Kirundo Rwanda hail recorded in some locations during the first half of June Gitobe Mugina Butihinda Mabayi Marangara Vumbi have caused agricultural losses and disturbed maturing Gashoho Nyamurenza Muyinga Mwumba bean crops....; Rugombo Cibitoke Muyinga Busiga Kiremba Gasorwe Murwi Kabarore Ngozi Bukinanyana Gashikanwa Kayanza Ngozi Tangara Muruta Gahombo Gitaramuka Buganda Buhinyuza Gatara Ruhororo Musigati Kayanza Kigamba ►Despite improvement of production in Season 2011A (3% Bubanza Muhanga Buhiga Bubanza Maton go Bugenyuzi Mwakiro Mishiha Gihogazi increase comparing to 2010B), the food deficits remain high Rango Mutaho Cankuzo Mpanda Karuzi Gihanga Buk eye Mutumba Rugazi Cankuzo for the second semester of the year, notably because the Mbuye Gisagara Muramvya Bugendana Nyabikere Mutimbuzi Shombo Bweru Muramvya Cendajuru imports that could supplement those production deficits are Buja Rutegama Isale Kiganda Giheta Ndava Butezi Mairie Mugongomanga reduced by the sub-regional food crisis. … ; Gisuru Kanyosha Gitega Ruyigi Buja Rusaka Nyabihanga Nyabiraba Gitega Ruyigi MutamRbuural Mwaro Kabezi Kayokwe ► Households victims of various climate disturbances Makebuko Mukike Gisozi Nyanrusange Butaganzwa Itaba Kinyinya Muhuta Bisoro Gishubi recorded in season 2011B and those with low resilience Nyabitsinda Mugamba Bugarama Ryansoro Bukirasazi capacity have not taken advantage of conducive conditions Matana Buraza Musongati Giharo D for a good production of Season 2011B and so remain Burambi R Mpinga-Kayove a Buyengero i Songa C Rutovu Rutana n Rutana a vulnerable to food insecurity. -

BURUNDI on G O O G GITARAMA N Lac Vers KIBUYE O U Vers KAYONZA R R a KANAZI Mugesera a Y B N a a BIRAMBO Y K KIBUNGO N A

29°30' vers RUHENGERI v. KIGALI 30° vers KIGALI vers RWAMAGANA 30°30' Nyabar BURUNDI on go o g GITARAMA n Lac vers KIBUYE o u vers KAYONZA r r a KANAZI Mugesera a y b n a a BIRAMBO y k KIBUNGO N A M RUHANGO w A D o N g A Lac o Lac BURUNDI W Sake KIREHE Cohoha- R Nord vers KIBUYE KADUHA Chutes de A a k r vers BUGENE NYABISINDU a ge Rusumo Gasenyi 1323 g a Nzove er k K a A 1539 Lac Lac ag era ra Kigina Cohoha-Sud Rweru Rukara KARABA Bugabira GIKONGORO Marembo Giteranyi vers CYANGUGU 1354 Runyonza Kabanga 1775 NGARA 2°30' u Busoni Buhoro r a Lac vers NYAKAHURA y n aux Oiseaux bu a Murore Bwambarangwe u BUGUMYA K v Kanyinya Ru Ntega hwa BUTARE Ru A GISAGARA Kirundo Ruhorora k Gitobe a Kobero n e vers BUVAKU Ruziba y Mutumba ny 2659 Mont a iza r C P u BUSORO 1886 Gasura A Twinyoni 1868 Buhoro R Mabayi C MUNINI Vumbi vers NYAKAHURA Murehe Rugari T A N Z A N I E 923 Butihinda Mugina Butahana aru Marangara Gikomero RULENGE y Gashoho n 1994 REMERA a u k r 1818 Rukana a Birambi A y Gisanze 1342 Ru Rusenda n s Rugombo Buvumo a Nyamurenza iz Kiremba Muyange- i N Kabarore K AT Busiga Mwumba Muyinga IO Gashoho vers BUVAKU Cibitoke N Bukinanyana A 2661 Jene a L ag Gasorwe LUVUNGI Gakere w Ngozi us Murwi a Rwegura m ntw Gasezerwa ya ra N bu R Gashikanwa 1855 a Masango u Kayanza o vu Muruta sy MURUSAGAMBA K Buhayira b Gahombo Tangara bu D u ya Muramba Buganda E Mubuga Butanganika N 3° 2022 Ntamba 3° L Gatara Gitaramuka Ndava A Buhinyuza Ruhororo 1614 Muhanga Matongo Buhiga Musigati K U Bubanza Rutsindu I Musema Burasira u B B b MUSENYI I Karuzi u U Kigamba -

BURUNDI: Carte De Référence

BURUNDI: Carte de référence 29°0'0"E 29°30'0"E 30°0'0"E 30°30'0"E 2°0'0"S 2°0'0"S L a c K i v u RWANDA Lac Rweru Ngomo Kijumbura Lac Cohoha Masaka Cagakori Kiri Kiyonza Ruzo Nzove Murama Gaturanda Gatete Kayove Rubuga Kigina Tura Sigu Vumasi Rusenyi Kinanira Rwibikara Nyabisindu Gatare Gakoni Bugabira Kabira Nyakarama Nyamabuye Bugoma Kivo Kumana Buhangara Nyabikenke Marembo Murambi Ceru Nyagisozi Karambo Giteranyi Rugasa Higiro Rusara Mihigo Gitete Kinyami Munazi Ruheha Muyange Kagugo Bisiga Rumandari Gitwe Kibonde Gisenyi Buhoro Rukungere NByakuizu soni Muvyuko Gasenyi Kididiri Nonwe Giteryani 2°30'0"S 2°30'0"S Kigoma Runyonza Yaranda Burara Nyabugeni Bunywera Rugese Mugendo Karambo Kinyovu Nyabibugu Rugarama Kabanga Cewe Renga Karugunda Rurira Minyago Kabizi Kirundo Rutabo Buringa Ndava Kavomo Shoza Bugera Murore Mika Makombe Kanyagu Rurende Buringanire Murama Kinyangurube Mwenya Bwambarangwe Carubambo Murungurira Kagege Mugobe Shore Ruyenzi Susa Kanyinya Munyinya Ruyaga Budahunga Gasave Kabogo Rubenga Mariza Sasa Buhimba Kirundo Mugongo Centre-Urbain Mutara Mukerwa Gatemere Kimeza Nyemera Gihosha Mukenke Mangoma Bigombo Rambo Kirundo Gakana Rungazi Ntega Gitwenzi Kiravumba Butegana Rugese Monge Rugero Mataka Runyinya Gahosha Santunda Kigaga Gasave Mugano Rwimbogo Mihigo Ntega Gikuyo Buhevyi Buhorana Mukoni Nyempundu Gihome KanabugireGatwe Karamagi Nyakibingo KIRUCNanika DGaOsuga Butahana Bucana Mutarishwa Cumva Rabiro Ngoma Gisitwe Nkorwe Kabirizi Gihinga Miremera Kiziba Muyinza Bugorora Kinyuku Mwendo Rushubije Busenyi Butihinda -

This Publication Is Made Available Online by Swedish Institute Of

SIM SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF MISSION RESEARCH PUBLISHER OF THE SERIES STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA & MISSIO PUBLISHER OF THE PERIODICAL SWEDISH MISSIOLOGICAL THEMES (SMT) This publication is made available online by Swedish Institute of Mission Research at Uppsala University. Uppsala University Library produces hundreds of publications yearly. They are all published online and many books are also in stock. Please, visit the web site at www.ub.uu.se/actashop Le mouvement pentecottsteA • - Une communauté alternative au sud du Burundi, 1935-1960 GUNILLA NYBERG ÜSKARSSON Studia Missionalia Svecana XCV Distributor: The Swedish Institute ofMissionary Research, P.O. Box 1526, SE-751 45 Uppsala, Sweden Gunilla Nyberg Oskarsson Le mouvement pentecôtiste- une communauté alternative au sud du Burundi, 1935-1960 Akademisk avhandling som fôr avHi.ggande av teologie doktorsexamen vid Uppsala universitet kommer att offentligen fôrsvaras i sai IV, Universitetshuset, Uppsala, fredagen den 7 maj 2004, kl. 10.00 f.m. ABSTRACT Nyberg Oskarsson, Gunilla 2004: Le mouvement pentecôtiste- une communauté alternative au sud du Burundi, 1935-1960. Studia Missionalia Svecana XCV. 327 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-85424-86-2. This thesis is a contribution to a hitherto neglected area of research: The Pentecostal Churches, that are not part of African Indigenous Churches (AICs). It is a case study from the perspective of southern Burundi, the periphery of the ancient kingdom. The Pentecostal Movement in Burundi was born in the encounter between Swedish Pentecostal missionaries and the population in the southern part of the country. This study highlights what happened in that encounter. The thesis consists of six parts. The first is a survey if the Pentecostal Movement in Sweden. -

Reconciliation Process Challenges Learning from Past Experiences and Insights from the South African Reconciliation Process

DIALOGUE AND EXCHANGE PROGRAM REPORT Study Tour of the Burundian Truth and Reconciliation Commissioners Reconciliation process challenges Learning from past experiences and insights from the South African reconciliation process March 23–26, 2015 •Cape Town, South Africa PUBLISHED BY THE BURUNDI OFFICE OF THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE IN COLLABORATION WITH THE INSTITUTE FOR JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION, SOUTH AFRICA BuBURUNrundi: AdminDistIrative Map (23 Sept 2015) Ü RWANDA Bugabira Giteranyi Busoni Kirundo Kirundo Bwambarangwe Ntega Gitobe Mugina Vumbi Mabayi Butihinda Marangara Gashoho Rugombo MwumbaNyamurenza Muyinga Kiremba Kabarore Busiga Gasorwe Cibitoke Bukinanyana Gashikanwa Ngozi Murwi Kayanza Muyinga Tangara Muruta Ngozi Buganda Gitaramuka Buhinyuza GataraGahombo Ruhororo Musigati Kayanza Muhanga Kigamba Bubanza Mishiha Matongo Bugenyuzi Buhiga Butaganzwa Mwakiro DR CONGO Mutaho Bubanza Gihogazi Rango Cankuzo Mpanda Gihanga Rugazi Bukeye Karuzi Mutumba Muramvya Cankuzo Gisagara Mbuye Bugendana Nyabikere Mutimbuzi Mubimbi Muramvya Bweru Rutegama Shombo Cendajuru BujumburaNtahangwa Kiganda Giheta Isale Butezi Bujumbura MairieMukaza Ndava Kanyosha1 Mugongomanga Muha Ruyigi Gisuru Nyabiraba Rusaka Nyabihanga Gitega Ruyigi Bujumbura Rural Mwaro Kabezi Mutambu Kayokwe Gitega Gisozi Butaganzwa1 Mukike Nyanrusange Makebuko Itaba Gishubi Kinyinya Muhuta Bisoro Nyabitsinda Mugamba Ryansoro TANZANIA Bugarama Bukirasazi Matana Rumonge Buraza Musongati Burambi Bururi Mpinga-Kayove Giharo Buyengero Songa Rutovu Rutana Bururi Rutana Rumonge Gitanga LAKE TANGANYIKA Bukemba Vyanda Capital Makamba Vugizo Kayogoro Provincial capital Makamba National road Mabanda Nyanza-Lac Kibago Provincial road Province Commune 0 25 50 100 km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 23 Sept 2015 Sources: IGEBU, OCHA, OpenStreetMap. Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int Contents 1. -

BURUNDI – Complex Emergency

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BUREAU FOR HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE (BHR) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) BURUNDI – Complex Emergency Situation Report #1, Fiscal Year (FY) 2002 October 3, 2001 Note: this situation report updates Information Bulletin #1 for FY 2001 dated July 3, 2001 BACKGROUND The Tutsi minority, who represent 14% of Burundi’s total 6.6 million people, have dominated the country’s political, military, and economic arenas since national independence in 1962. Approximately 85% of Burundi’s population is Hutu, and approximately 1% is Batwa. In October 1993, the current cycle of violence began when members of the Tutsi-dominated army assassinated the first freely elected President, Melchoir Ndadaye (Hutu), sparking Hutu-Tutsi fighting in which more than 50,000 were reported killed. Ndadaye’s successor Cyprien Ntariyama (Hutu) was killed in a plane crash on April 6, 1994 alongside Rwandan President Habyarimana. Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu) took power and served as President until July 1996, when a coup brought current President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) to power. In August 2000, nineteen Burundi parties signed the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania overseen by the Burundi peace process facilitator, former South African President Nelson Mandela. The Arusha Peace Agreement includes provisions for an ethnically balanced army and legislature, and for democratic elections to take place after three years of transitional government. The three-year transition period is scheduled to begin on November 1, 2001 with President Pierre Buyoya serving for the first 18 months. The candidate of the “group of seven” parties (G7) representing Hutu interests, Domitien Ndayizeye, is designated Vice-President. -

09-SPAT De Bururi

Carte N°9 : SPAT DE BURURI REPUBLIQUE DU BURUNDI MINISTERE DE L’EAU, DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT, DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE ET DE L’URBANISME DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE, DU GENIE RURAL ET DE LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE FONCIER SCHEMA PROVINCIAL D’AMENAGEMENT Vers Mwaro ers Mukike DU TERRITOIRE DE BURURI V P R O V I N C E D E NYAGASASA M W A R O e r e g u M Vers Bujumbura Rural Mushwabure Nyagasumira P R O V I N C E D E MUGAMBA H Mugonere NYAGIHOTORA P R O V I N C E D E B U J U M B U R A R U R A L Musarara VYUYA TORA Nonya G I T E G A A Vers Bujumbura Rural G A W KIGANZA Kamira GASIBE GISENYI RUTUMO GIHANGA Kigezi DONZI Mugonera Masemba A Kibarazi Gatare M GITANDU A D KIRI Ruhororo ROBERO H Shanga MATANA Nyakija Rugata KIBUNGO BUTWE Naonva H Ziba KADIDAGI MUZENGA Kibarazi Kagoma CONDI MURAGO Matanga Ruhora Nyanjabaga KIVUBO MINAGO Cogo H-E S9 RUHORA MUYAMA S5 RUMEZA Musebeyi H RUMUMVU RUZIRA Cugaro MUYANGE MUSAVE Kigira RUVYIRONZA Nyeshombe H-E S8 Rusabagi Vers Rutana KAGONGO RN 7 Ngemwe KIRYAMA Kigira Muyoyozi RN 3 Kizuka Gazenyi Nyamusenyi Munaboke S6 MUHEKA KAJONDI Y Sama ove Muhorera Mugure MUZINGA MUDENDE KIZUKA H-E Mureba H S4 JIJI RUTUNDWE Munega JIJI Sources du Nil S7 Nyagwijima Sambwe Dundwe BURURI Mutandu GASANDA MWANGE Musihazi PDUI RN 17 KIREMBA MUHWEZA Siguvyaye MTUTU Siguvyaye PDUI BUTA H-E H S10 H NYAGASAKA NGENDO JIJI RUMONGE Koga RN 16 MURAMBI MIBIRA L A C NEMA BURUHUKIRO T A N G A N Y I K A Buzimba MUNINI MUTAMBARA P R O V I N C E D E GITSIRO Muyomvyi S3 KARAGARA KIRUNGU Vers Makamba R U T A N A GATETE -

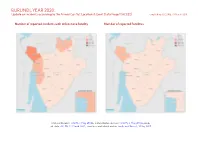

BURUNDI, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021

BURUNDI, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 BURUNDI, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 406 124 164 Conflict incidents by category 2 Strategic developments 100 0 0 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Battles 66 39 144 Riots 50 12 12 Methodology 3 Explosions / Remote 17 6 9 Conflict incidents per province 4 violence Protests 9 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 648 181 329 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 BURUNDI, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

![International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5984/international-commission-of-inquiry-for-burundi-final-report-1-2-3985984.webp)

International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2

[International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report]1 2 Contents Part I: Introduction I. Creation of the Commission II. The Commission’s Mandate III. General Methodology IV. Activities of the Commissions A. 1995 B. 1996 V. Difficulties in the Commission’s Work A. The time elapsed since the events under investigation B. Ethnic polarization in Burundi C. The security situation in Burundi D. Inadequacy of resources VI. Acknowledgements VII. Documents and Recordings Part II: Background I. Geographical Summary of Burundi II. Population III. Administrative Organization IV. Economic Summary V. Historical Summary VI. The Presidency of Melchior Ndadaye VII. Events After the Assassination Part III: Investigation of the Assassination I. Object of the Inquiry II. Methodology III. Access to Evidence IV. Work of the Commission V. The Facts According to Witnesses A. 3 July 1993 B. 10 July 1993 C. 11 October 1993 1 Note: This title is derived from information found at Part I:1:2 of the report. No title actually appears at the top of the report. 2 Posted by USIP Library on: January 13, 2004 Source Name: United Nations Security Council, S/1996/682; received from Ambassador Thomas Ndikumana, Burundi Ambassador to the United States Date received: June 7, 2002 D. Monday, 18 October 1993 E. Tuesday, 19 October 1993 F. Wednesday, 20 October 1993 G. Thursday, 21 October 1993, Midnight to 2 a.m. H. Thursday, 21 October 1993, 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. I. Thursday, 21 October 1993, 6 a.m. to noon J. Thursday, 21 October 1993, Afternoon VI. Analysis of Testimony VII. -

Rapport De Septembre 2019

Association Burundaise pour la Protection des Droits Humains et des Personnes Détenues «A.PRO.D.H» RAPPORT DE SEPTEMBRE 2019 Octobre 2019 APRODH-Rapport Mensuel-Septembre 2019 Page 1 ACRONYMES CDS : Centre de Santé CICR : Comité International de la Croix Rouge CENI : Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante CEPI : Commission Electorale Provinciale Indépendante CMCL : Centre de rééducation des Mineurs en Conflits avec la Loi CNDD-FDD : Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Front pour la Défense de la Démocratie CNL : Congrès National pour la Liberté ECOFO : Ecole Fondamentale FBU : Franc Burundais FRODEBU : Front pour la Démocratie au Burundi HPRC : Hôpital Prince Régent Charles MSD : Mouvement pour la Solidarité et la Démocratie ONLCT : Observatoire National pour la Lutte contre la Criminalité Transnationale OPJ : Officier de Police Judiciaire OPP : Officier de Police Principal PJ : Police Judiciaire RANAC : Rassemblement National pour le Changement SIDA : Syndrome d’Immuno - Déficience Acquise SNR : Service National de Renseignement TGI : Tribunal de Grande Instance APRODH-Rapport Mensuel-Septembre 2019 Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION Le présent rapport traite des différentes violations des droits humains commises dans diverses localités du pays au cours du mois de septembre 2019. Bien entendu, il ne prétend pas mettre en évidence tous les cas d’atteinte portée aux droits humains au cours du mois concerné, certains ayant pu échapper à notre observation. Notre rapport commence par une analyse contextuelle de la situation sécuritaire, politique, judiciaire et sociale car, pour nous, une telle approche nous permet de faire une bonne appréciation de la situation des droits humains dans le pays. Ainsi, des exactions commises par les Imbonerakure (jeunes affiliés au parti au pouvoir, le CNDD/FDD), tantôt contre des personnes membres du parti CNL , des attaques sans répit des groupes armés non identifiés sur les voies publiques, des armes retrouvées ça et là, ont été au centre des perturbations de la sécurité. -

Kigoma Region

G Mabanza Nyakabingo Munzaga Munyika Rumeza GKarambi Muka Kabingo Sorwe Nyarubimba Dangara Gakombe Kivoga Kavumu Kibimba Bigoti Mabuga Mutangaro Gisuma Jurugati Kumana Karambi Songorere CDS Ruvumu Karwa Mujenjero Mihama Nyamiyaga Rarire Musumba Gishirwe Gashirwe Buta Gitega Bunya Nyempongo Mwebeya TANZANIA - KigomaRuvumvu Region - Base Map and Refugee Situation as of 19 May 2015Karera I Kinaba Muyaga Musenyi Manyoni Bihari CDS Gahanda Gasanga Kinyonzo KIVOGA Kararo Kimiranzovu Nyaho Kinyovu Butimbo Muvumu Kavuza Rukoma Rwansongo Kiryama Ruhuma Kanyamiyoka Baziro Ntirwonza Kagera Gitwa Rukoma Buranga Mitegwe G Nyabisindu Muhama Nyobwe Gitezi Muhanda G Kagera Matutu Mungwa Mugarama Rubaho Sebeyi Kayange Kiryama Muyogoro Kivoga Kabingo Ruranga Giheko Kibasi Taba Musagara St. Sára Muzibaziba Rutare CDS Jenda Rukina Ramvya Gicumbi Kwitaba Gihoro Fuku Ruringanizo Salkahazy Nkati Karera II CDS Rugunga Gasaka Bitare Butezi Gasunu Kinama Karambi Mubanga Murambi Kijima Gitaba ± Kame Kwitaba CDS Mbariza Rutovu Hospital Musenyi G CDS Kiguhu MuhekaG Kayange Kajondi Ntove Nzokande Ngina Rukobe G Mudende Tagara CDS Ndago Nyakarambo G Kitugamwa Nyamirambo Nyanzuki Migende Sarutoke Nyamiyaga KajondiG Rutovu Biteka Muyange Ningwe Kivoga G Kivumu G Rwego Rwira Kadende Kibinzi Kanyabitumwe Nyesoko Kabirizi Mika Rugongwe Kiguhu Mpinga Musagara Ruminamina Kuwingwa Kiririsi Shoti Gakobe Mudende G Ruhando Bugombe Nyagiti Gikokoma Ndago Nyagatwe CDS Kadina Busigo Gasasa Muhafu Vumbi Kuwigaro Rushiha Gisorwe Gikinga Nyakabanda KIBONDO CDS Mubuga Rwamabuye Nyavyamo