Wannofri Samri.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peran Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said Dalam Memperjuangkan Hak-Hak Perempuan Indonesia (1926-1965)

PERAN HAJJAH RANGKAYO RASUNA SAID DALAM MEMPERJUANGKAN HAK-HAK PEREMPUAN INDONESIA (1926-1965) E-JURNAL Oleh: Esti Nurjanah 13406241069 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2017 PERAN HAJJAH RANGKAYO RASUNA SAID DALAM MEMPERJUANGKAN HAK-HAK PEREMPUAN INDONESIA (1926-1965) Oleh: Penulis 1 : Esti Nurjanah Penulis 2 : Dr. Dyah Kumalasari, M.Pd. ABSTRAK Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said merupakan tokoh Sumatera Barat sekaligus pahlawan nasional Indonesia yang berperan memperjuangkan hak-hak perempuan Indonesia tahun 1926-1965. Penelitian ini mempunyai tujuan untuk mengetahui: (1) latar belakang kehidupan Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said, (2) perjuangan Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said pada masa kolonial tahun 1926-1945, (3) perjuangan Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said pasca kemerdekaan Indonesia tahun 1946-1965. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode penelitian sejarah Kuntowijoyo yang terdiri dari lima tahap. Pertama pemilihan topik. Kedua pengumpulan data (heuristik) yang terdiri dari sumber primer dan sekunder. Ketiga kritik sumber (verifikasi). Keempat penafsiran (interpretasi). Kelima penulisan sejarah (historiografi). Hasil penelitian ini adalah: (1) Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said memiliki latar belakang keluarga yang berasal dari kalangan ulama dan pengusaha terpandang. Faktor lingkungan yang syarat dengan adat Minang dan agama Islam, mempengaruhi kepribadiannya sehingga tumbuh menjadi perempuan berkemauan keras, tegas, dan taat pada syariat Islam, (2) perjuangan Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said dimulai dengan bergabung dalam Sarekat Rakyat tahun 1926. Pada masa pendudukan Belanda hingga Jepang, dirinya aktif mengikuti berbagai organisasi. Beliau dikenal sebagai orator ulung, pendidik yang tegas serta penulis majalah, (3) perjuangan Hajjah Rangkayo Rasuna Said pasca kemerdekaan Indonesia lebih banyak di bidang politik. Beliau terus mengembangkan karirnya dalam Parlemen mulai tingkat lokal hingga nasional di Jakarta. -

Newsletter KBMJ 2020 Jan-Mac Final Version

NEWSLETTER (JANUARY - MARCH 2020) Jl. H.R. Rasuna Said, Kav. X/6, No. 1 -3, Kuningan, 12950, Jakarta Selatan @[email protected] @EmbassyMalaysiaJakarta (021) 5224947 @MYEmbJKT +62 813 8081 3036 (After working hours only) @MYEmbJKT Assalamulaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh Salam Persahabatan Malaysia-Indonesia 2020 is a promising year for bilateral rela�ons between Malaysia-Indonesia. From the mul�-faceted ac�vi�es and engagements undertaken in 2019 (May to Dec), ranging from the high-level visits to the inaugural “Misi Promosi Malaysia”, I consider 2020 a follow-up year to realize all those ini�a�ves and translate them into beneficial outcomes for the two countries. However, the first quarter of the year had witnessed an unprecedented challenges to all of us. The Covid-19 outbreak was made the worse ahead of us. We are too affected by this pandemic in many ways, and s�ll remain commi�ed to build the already strong and good rela�onship with Indonesia. Our focus and strength in this trying �mes are rendered to assists Malaysians in need. We pray for Allah Subhanahu Wata’ala for this pandemic to subside and certainly look forward to return to normalcy soon. Nevertheless, let us be wary, and not let our guard down. Datuk Zainal Abidin Bakar Highlights of 2019 Highlights of Quarterly Newsle�er Malaysia Outreach Malaysia-Indonesia COVID-19 Alert Promotional Missions Programmes Then & Now ENGAGEMENT (SILATURRAHMI) JAN-MAC Sila layari media sosial Kedutaan untuk melihat aktiviti yang dijalankan #diplomasiserumpun MALAYSIA PROMOTIONAL MISSIONS His Excellency Datuk Zainal Abidin Bakar, Ambassaddor of Malaysia to RI ocially launched the Malaysia Health- care Expo 2020 at the Atrium Forum, Kelapa Gading Mall on 6 February 2020. -

Domain Dan Bahasa Pilihan Tiga Generasi Etnik Bajau Sama Kota Belud

96 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), Volume 5, Issue 7, (page 96 - 107), 2020 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) Volume5, Issue 7, July 2020 e-ISSN : 2504-8562 Journal home page: www.msocialsciences.com Domain dan Bahasa Pilihan Tiga Generasi Etnik Bajau Sama Kota Belud Berawati Renddan1, Adi Yasran Abdul Aziz1, Hasnah Mohamad1, Sharil Nizam Sha'ri1 1Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) Correspondence: Berawati Renddan ([email protected]) ABstrak ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Etnik Bajau Sama merupakan etnik kedua terbesar di negeri Sabah. Kawasan petempatan utama etnik Bajau Sama di Sabah terletak di Kota Belud di Pantai Barat. Sebagai masyarakat yang dwibahasa, pilihan penggunaan bahasa masyarakat yang beragama Islam ini adalah berbeza-beza mengikut generasi dan domain yang berkemungkinan tidak berpihak kepada bahasa ibunda. Teori Analisis Domain (Fishman) diterapkan bagi mengkaji pilihan bahasa dalam domain khusus oleh peserta kajian dari Kampung Taun Gusi, Kota Belud, Sabah. Kaedah tinjauan dengan soal selidik digunakan untuk mendapatkan maklumat daripada generasi pertama (GI), kedua (GII) dan ketiga (GIII). Nilai min bagi setiap kumpulan dlam domain kekeluargaan menunjukkan bahawa GI dan GII Lebih banyak menggunakan bahasa Bajau Sama manakala GIII lebih cenderung kepada bahasa Melayu. Dalam domain kejiranan, GI memilih bahasa Bajau Sama namun GII dan GIII masing-masing memilih BM. Walau bagaimanapun, dalam domain pendidikan, keagamaan, perkhidmatan dan jual-beli, semua generasi memilih bahasa Melayu. Penemuan yang paling penting ialah generasi muda (GIII) kini sudah beralih kepada bahasa Melayu dalam domain kekeluargaan dan domain awam. Generasi ini bertindak sebagai pemangkin peralihan bahasa yang mendatangkan ancaman kepada daya hidup bahasa Bajau Sama, khususnya dalam domain tidak formal seperti kekeluargaan dan kejiranan. -

Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke

Between G elanggang and Lekra: Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke Introduction During the first decade of the New Order, the idea of the autonomy of art was the unchallenged basis for all art production considered legitimate. The term encompasses two significant assumptions. First, it includes the idea that art and/or its individual categories are recognized within society as independent sub-systems that make their own rules, i.e. that art is not subject to influences exerted by other social sub-systems (politics and religion, for example). Secondly, it entails a complex of aesthetic notions that basically tend to exclude all non-artistic considerations from the aesthetic field and to define art as an activity detached from everyday life. An aesthetics of autonomy can create problems for its adherents, as a review of recent occidental art and literary history makes clear. Artists have attempted to overcome these problems by reasserting social ideals (e.g. as in naturalism) or through revolt, as in the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century which challenged the aesthetic norms of the autonomous work of art in order to relocate aesthetic experience at a pivotal point in relation to individual and social life.* 1 * This article is based on parts of my doctoral thesis, Angkatan 45. Literaturkonzeptionen im gesellschafipolitischen Kontext (Berlin: Reimer, 1993). I thank the editors of Indonesia, especially Benedict Anderson, for helpful comments and suggestions. 1 In German studies of literature, the institutionalization of art as an autonomous field and its aesthetic consequences is discussed mainly by Christa Burger and Peter Burger. -

INDO 7 0 1107139648 67 76.Pdf (387.5Kb)

THE THORNY ROSE: THE AVOIDANCE OF PASSION IN MODERN INDONESIAN LITERATURE1 Harry Aveling One of the important shortcomings of modern Indonesian literature is the failure of its authors, on the whole young, well-educated men of the upper and more modernized strata of society, to deal in a convincing manner with the topic of adult heterosexual passion. This problem includes, and partly arises from, an inadequacy in portraying realistic female char acters which verges, at times, on something which might be considered sadism. What is involved here is not merely an inability to come to terms with Western concepts of romantic love, as explicated, for example, by the late C. S. Lewis in his book The Allegory of Love. The failure to depict adult heterosexual passion on the part of modern Indonesian authors also stands in strange contrast to the frankness and gusto with which the writers of the various branches of traditional Indonesian and Malay litera ture dealt with this topic. Indeed it stands in almost as great a contrast with the practice of Peninsular Malay literature today. In Javanese literature, as Pigeaud notes in his history, The Literature of Java, "Poems and tales describing erotic situations are very much in evidence . descriptions of this kind are to be found in almost every important mythic, epic, historical and romantic Javanese text."^ In Sundanese literature, there is not only the open violence of Sang Kuriang's incestuous desires towards his mother (who conceived him through inter course with a dog), and a further wide range of openly sexual, indeed often heavily Oedipal stories, but also the crude direct ness of the trickster Si-Kabajan tales, which so embarrassed one commentator, Dr. -

THE TRANSFORMATION of TRADITIONAL MANDAILING LEADERSHIP in INDONESIA and MALAYSIA in the AGE of GLOBALIZATION and REGIONAL AUTONOMY by Abdur-Razzaq Lubis1

THE TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL MANDAILING LEADERSHIP IN INDONESIA AND MALAYSIA IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION AND REGIONAL AUTONOMY by Abdur-Razzaq Lubis1 THE NOTION OF JUSTICE IN THE ORIGIN OF THE MANDAILING PEOPLE The Mandailing people, an ethnic group from the south-west corner of the province of North Sumatra today, went through a process of cultural hybridization and creolization centuries ago by incorporating into its gene pool the diverse people from the archipelago and beyond; adopting as well as adapting cultures from across the continents. The many clans of the Mandailing people have both indigenous as well as foreign infusions. The saro cino or Chinese-style curved roof, indicates Chinese influence in Mandailing architecture.(Drs. Z. Pangaduan Lubis, 1999: 8). The legacy of Indian influences, either direct or via other peoples, include key political terms such as huta (village, generally fortified), raja (chief) and marga (partilineal exogamous clan).(J. Gonda, 1952) There are several hypotheses about the origin of the Mandailing people, mainly based on the proximity and similarity of sounds. One theory closely associated with the idea of governance is that the name Mandailing originated from Mandala Holing. (Mangaraja Lelo Lubis, : 3,13 & 19) Current in Mandailing society is the usage 'Surat Tumbaga H(K)oling na so ra sasa' which means that the 'Copper H(K)oling cannot be erased'. What is meant is that the adat cannot be wiped out; in other words, the adat is everlasting. Both examples emphasises that justice has a central role in Mandailing civilization, which is upheld by its judicial assembly, called Na Mora Na Toras, the traditional institution of 1 The author is the project leader of The Toyota Foundation research grant on Mandailing migration, cultural heritage and governance since 1998. -

IBNU AJAN.Tif

SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MANDAILING’S TRADITIONAL HOUSE BAGAS GODANG SKRIPSI Submited in Partial Fulfillment of the requirement For the Degree of Sarjana Pendidikan (S.Pd) English Education program By: IBNU AJAN HASIBUAN 1402050064 FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 i ABSTRACT Hasibuan, Ibnu Ajan. 1402050064 Semiotic Analysis of Mandailing’s Traditional House Bagas Godang. Skripsi, English Education Program of the Faculty of the Teacher Training and Education, University of Muhammadiyah North Sumatera. Medan. 2018 The Objective of this research were to find out the kinds and the meaning of semiotic of Mandailing’s Traditional House Bagas Godang in Panyabuangan City especially Pidoli Dolok Village. This research used qualitative method in accordance with the theory of Charles Sanders Pierce and based on the semiotic fields especially Culture code such as architecture and ornamnet. The descriptive technique was carried out in analyzing data by Huberman and miles with the steps are reduction, display and verification data. The source of data was taken from the people who lives in Pidoli Dolok by Observation and interview. The finding of this research showed there are only six kids of semiotic in Bagas Godang are: Sinsign (1), Legisign (2), Icon (3), Index (1), Symbol (13), and decisgn (2) and the meaning of semiotic kind are conveying their hoping, advicing, rules/norm and govermet system with what have been presented in Bagas Godang (Symbol). It can be concluded that the following: there are three kind of semiotic from use of semiotic Bagas Godang as the sign: Representamen the meaning by human, object which present or is within “cognition” a person or group of people and interpretent of someone based on the object it sees fit with the fact. -

Kritik Buya Hamka Terhadap Adat Minangkabau Dalam Novel

KRITIK BUYA HAMKA TERHADAP ADAT MINANGKABAU DALAM NOVEL TENGGELAMNYA KAPAL VAN DER WIJCK (Humanisme Islam sebagai Analisis Wacana Kritis) SKRIPSI Diajukan kepada Fakultas Ushuluddin dan Pemikiran Islam Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Strata Satu Filsafat Islam Oleh: Kholifatun NIM 11510062 PROGRAM STUDI FILSAFAT AGAMA FAKULTAS USHULUDDIN DAN PEMIKIRAN ISLAM UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2016 MOTTO Kehidupan itu laksana lautan: “Orang yang tiada berhati-hati dalam mengayuh perahu, memegang kemudi dan menjaga layar, maka karamlah ia digulung oleh ombak dan gelombang. Hilang di tengah samudera yang luas. Tiada akan tercapai olehnya tanah tepi”. (Buya Hamka) vi PERSEMBAHAN “Untuk almamaterku UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta fakultas Ushuluddin dan Pemikiran Islam program studi Filsafat Agama” “Untuk kedua orang tuaku bapak Sukasmi dan mamak Surani” “Untuk calon imamku mas M. Nur Arifin” vii ABSTRAK Kholifatun, 11510062, Kritik Buya Hamka Terhadap Adat Minangkabau dalam Novel Tenggelamnya Kapal Van Der Wijck (Humanisme Islam sebagai Analisis Wacana Kritis) Skripsi, Yogyakarta: Program Studi Filsafat Agama Fakultas Ushuluddin dan Pemikiran Islam UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta, 2015/2016. Novel adalah salah satu karya sastra yang dapat menjadi suatu cara untuk menyampaikan ideologi seseorang. Pengarang menciptakan karyanya sebagai alat untuk menyampaikan hasil dari pengamatan dan pemikirannya. Hal tersebut dapat dilihat dari bagaimana cara penyampaian serta gaya bahasa yang ia gunakan dalam karyanya. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui apa pemikiran Hamka di balik novelnya yang berjudul Tenggelamnya Kapal Van Der Wijck. Dengan latar belakang seorang agamawan, bagaimana Buya Hamka menyikapi adat Minangkabau yang bersistem matrilineal. Untuk menganalisis novel Tenggelamnya Kapal Van Der Wijck ini metode yang digunakan adalah metode analisis wacana kritis Norman Fairclough. -

What Is Indonesian Islam?

M. Laffan, draft paper prepared for discussion at the UCLA symposium ‘Islam and Southeast Asia’, May 15 2006 What is Indonesian Islam? Michael Laffan, History Department, Princeton University* Abstract This paper is a preliminary essay thinking about the concept of an Indonesian Islam. After considering the impact of the ideas of Geertz and Benda in shaping the current contours of what is assumed to fit within this category, and how their notions were built on the principle that the region was far more multivocal in the past than the present, it turns to consider whether, prior to the existance of Indonesia, there was ever such a notion as Jawi Islam and questions what modern Indonesians make of their own Islamic history and its impact on the making of their religious subjectivities. What about Indonesian Islam? Before I begin I would like to present you with three recent statements reflecting either directly or indirectly on assumptions about Indonesian Islam. The first is the response of an Australian academic to the situation in Aceh after the 2004 tsunami, the second and third have been made of late by Indonesian scholars The traditionalist Muslims of Aceh, with their mystical, Sufistic approach to life and faith, are a world away from the fundamentalist Islamists of Saudi Arabia and some other Arab states. The Acehnese have never been particularly open to the bigoted "reformism" of radical Islamist groups linked to Saudi Arabia. … Perhaps it is for this reason that aid for Aceh has been so slow coming from wealthy Arab nations such as Saudi Arabia.1 * This, admittedly in-house, piece presented at the UCLA Colloquium on Islam and Southeast Asia: Local, National and Transnational Studies on May 15, 2006, is very much a tentative first stab in the direction I am taking in my current project on the Making of Indonesian Islam. -

Chapter I Introduction

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Background of the Study Indonesia consits of many ethnic groups. Every ethnic groups has a particular language. Language is very important. Language is considered an important symbol of a minority group’s identity for maintain ( Holmes: 2001). For example Mandailingnase language is a part of culture. John said “Language as sentences and speech acts, as an extension of the more biologically fundamental forms of intentionality that we have in belief, desire, memory and intention, and to see those in turn as developments of even more fundamental forms of intentionality, especially, perception and intentional action”. Mandailingnese language was used by Mandailingnese people. Mandailingnese language used in regency of Mandailing Natal ( MADINA). Mandailingnese spreaded and moved the land in Medan . One of the destination was Bandar Khalipah located in Medan. They make their own community for years. It was proved by many people speak mandailingnese language in the era. When mandailingnese live Bandar Khalipah, They use their vernacular language to each other by using mandailingnese language. Although Mandalingnese community live side by side with Javanese. Javanese is one of the bigest population and Mandailingnese in Bandar Khalippah, followed by Mandailingnese. Mandailingnese people who live in Bandar Khalipah ever used mandailing language to Mandailingnese people. But now mandailingnese people can not used 1 2 it anymore. It is proved which the next generation especially teenagers can not used it anymore. According to Abrams & Strogatz (2003) language shift as a competition process in which the numbers of speakers of each language vary as a function both of internal (as the net outcome of birth, death, immigration and emigration rates of native speakers), and of gains and losses owing to language shift . -

The Last Sea Nomads of the Indonesian Archipelago: Genomic

The last sea nomads of the Indonesian archipelago: genomic origins and dispersal Pradiptajati Kusuma, Nicolas Brucato, Murray Cox, Thierry Letellier, Abdul Manan, Chandra Nuraini, Philippe Grangé, Herawati Sudoyo, François-Xavier Ricaut To cite this version: Pradiptajati Kusuma, Nicolas Brucato, Murray Cox, Thierry Letellier, Abdul Manan, et al.. The last sea nomads of the Indonesian archipelago: genomic origins and dispersal. European Journal of Human Genetics, Nature Publishing Group, 2017, 25 (8), pp.1004-1010. 10.1038/ejhg.2017.88. hal-02112755 HAL Id: hal-02112755 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02112755 Submitted on 27 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 1004–1010 Official journal of The European Society of Human Genetics www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE The last sea nomads of the Indonesian archipelago: genomic origins and dispersal Pradiptajati Kusuma1,2, Nicolas Brucato1, Murray P Cox3, Thierry Letellier1, Abdul Manan4, Chandra Nuraini5, Philippe Grangé5, Herawati Sudoyo2,6 and François-Xavier Ricaut*,1 The Bajo, the world’s largest remaining sea nomad group, are scattered across hundreds of recently settled communities in Island Southeast Asia, along the coasts of Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. -

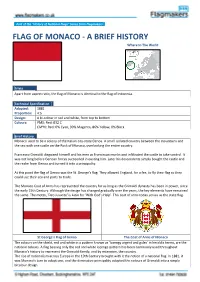

FLAG of MONACO - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF MONACO - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia Apart from aspect ratio, the flag of Monaco is identical to the flag of Indonesia. Technical Specification Adopted: 1881 Proportion: 4:5 Design: A bi-colour in red and white, from top to bottom Colours: PMS: Red: 032 C CMYK: Red: 0% Cyan, 90% Magenta, 86% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History Monaco used to be a colony of the Italian city-state Genoa. A small isolated country between the mountains and the sea with one castle on the Rock of Monaco, overlooking the entire country. Francesco Grimaldi disguised himself and his men as Franciscan monks and infiltrated the castle to take control. It was not long before Genoan forces succeeded in ousting him. Later his descendents simply bought the castle and the realm from Genoa and turned it into a principality. At this point the flag of Genoa was the St. George’s flag. They allowed England, for a fee, to fly their flag so they could use their sea and ports to trade. The Monaco Coat of Arms has represented the country for as long as the Grimaldi dynasty has been in power, since the early 15th Century. Although the design has changed gradually over the years, the key elements have remained the same. The motto, 'Deo Juvante' is Latin for 'With God's Help'. This coat of arms today serves as the state flag. St George’s Flag of Genoa The Coat of Arms of Monaco The colours on the shield, red and white in a pattern known as 'lozengy argent and gules' in heraldic terms, are the national colours.