Hudson Rising on View March 1 – August 4, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson Rising on View March 1 – August 4, 2019

Hudson Rising On view March 1 – August 4, 2019 Selected PR Images The New-York Historical Society explores 200 years of ecological change, artistic inspiration, and environmental activism along the Hudson River in Hudson Rising. The exhibition features celebrated Hudson River School paintings, artifacts, and stories that evoke a journey through Hudson River landscapes and weave together 200 years of history from the industrial era to today. Much more than a body of water, the Hudson River and its environs have provided habitat for humans and hundreds of species of fish, birds, and plants; offered an escape for city-dwellers; and became a battleground between industrialists and environmental activists. Writers and artists have captured the river in paintings, drawings, literature, and photographs, and surveyors and scientists have mapped and measured every aspect of it. Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: Desolation, 1833-1836, New-York Historical Society, Gift of the New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts, 1858.5 Course of Empire is a panoramic series of five paintings intended to inspire reflection on the meaning of “progress.” Shown in a prelude to the exhibition, the first three paintings depict the transformation of a pristine landscape into a new and thriving city. The final two— including — Desolation chart its dramatic decline, leading to the fall of an entire civilization. Model of the Mary Powell, 1947. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mr. Edward Hungerford Wood- and coal-fired steamboats made Hudson journeys easy, cheap, and reliable, carrying upriver New York City’s burgeoning population and manufactured goods. They brought back ice, bricks, iron, coal, and lumber. -

SPANISH FORK PAGES 1-20.Indd

November 14 - 20, 2008 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, November 14 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey b News (N) b CBS Evening News (N) b Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Threshold” The Price Is Right Salutes the NUMB3RS “Charlie Don’t Surf” News (N) b (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight (N) b Troops (N) b (N) b Letterman (N) KJZZ 3 High School Football The Insider Frasier Friends Friends Fortune Jeopardy! Dr. Phil b News (N) Sports News Scrubs Scrubs Entertain The Insider The Ellen DeGeneres Show Ac- News (N) World News- News (N) Access Holly- Supernanny “Howat Family” (N) Super-Manny (N) b 20/20 b News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4 tor Nathan Lane. (N) Gibson wood (N) b line (N) wood (N) (N) b News (N) b News (N) b News (N) b NBC Nightly News (N) b News (N) b Deal or No Deal A teacher returns Crusoe “Hour 6 -- Long Pig” (N) Lipstick Jungle (N) b News (N) b (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night KSL 5 News (N) to finish her game. b Jay Leno (N) b TBS 6 Raymond Friends Seinfeld Seinfeld ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (G, ’39) Judy Garland. (8:10) ‘Shrek’ (’01) Voices of Mike Myers. -

The Magazine of 3-Dimensional Imaging, Past & Present

THE MAGAZINE OF 3-DIMENSIONAL IMAGING, PAST & PRESENT May/)une 1996 Volume 23, Number 2 A PuMk.tion d NATIONAL STEREOScoPlC ASSOCIATION, INC. An Invitati09 to Share Your Best Stereo Images ASSIGNMENT~=D with the World! New Assignment: "Stereo Impact" hile we select the final entries in the "Weather" Wassignment for the next couple of issues, we hope people will start going through their files (or drawers of yet-to-be-mounted slides or prints) with the new "Stereo Impact" assignment in mind. This one's wide open for ANY subject that truly required stereographic imaging to be under- stood or appreciated by those who didn't see it in person. In other words, those things or places that inspire comments along the lines of "Wow! This was just made for stereo!" The best of these are shots "Ice Chamber" by Michael McKinney of Hawthorne, CA may look like it was taken in an which are not just greatly ice cave but it's actually the back side of a waterfall, frozen solid in the winter of 1994 enhanced by stereo, but which lit- near Teluride, CO. When Michael and his wife hiked up the canyon to the falls, they dis- erally depend on stereo to make covered two ice climbers on it. visual sense or to reveal more than a confusing clutter of elements. (Views of complex machinery or dense, tangled forests are often among these sorts of images.) Nearly everybody who's shot even a few rolls of stereos has at least one view that could qualify here. -

Annual Dinner Set for October 23 Featuring Adirondack Singer, Songwriter and Storyteller Chris Shaw

JULY-SEPTEMBER 2009 No. 0904 chepontuc — “Hard place to cross”, Iroquois reference to Glens Falls hepontuc ootnotes C T H E N E W S L E tt E R O F T H E G L E N S F ALLS- S ARAFT O G A C H A P T E R O F T H E A DIRO N DA C K M O U nt AI N C L U B Annual Dinner set for October 23 Featuring Adirondack Singer, Songwriter and Storyteller Chris Shaw ark your calendars! Please Festival, and the Chautauqua join your fellow ADKers on Institute, as well as music halls, Friday, October 23, for our festivals, and coffee houses across Mannual Chapter Dinner. the US and Europe. He has pro- After years trekking to Glens Falls duced a number of TV soundtracks for dinner, our Saratoga County for Public Television. Chris wrote members will be closer to home this the soundtrack and was “the voice year. The newly redone Holiday of Seneca Ray” on the television Inn on South Broadway in Saratoga special “Seneca Ray Stoddard: An Springs has off-street parking, rea- American Original” seen coast to sonable prices and friendly, home- coast on PBS. Most recently, a live town service. concert special called “Chris Shaw: We are honored to welcome Live in Concert” is showing on PBS the wonderful, funny, charismatic stations across the country Christopher Shaw. Chris is the real Shaw has nine recordings deal. In a musical age where surface under his belt with another to be often replaces talent, and sincerity is released this spring. -

Artists' Perspectives: Envisioning the World

Evenings for Educators Artists’ Perspectives: Envisioning the World ALK THROUGH THE GALLERIES AT LACMA AND YOU’LL RECOGNIZE THE OBVIOUS: ARTISTS SEE the world in different ways. The lonG and colorful paintinG Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio (1980) is the work of Los Angeles–based artist David Hockney, Wwhose distinctive use of bright colors and bold patterns captures his view of a vibrant city. Step into another gallery and face portraits, now thousands of years old, of calm, stately people, their legs and faces in profile and their broad shoulders shown frontally. Here are the people of ancient Egypt, as represented by their artists. • What explains the distinctive ways artists see the world and its peoples? These curriculum materials consider how artists envision the world. Separate from the act of observing, envisioning calls attention to the mental act of forming an image with the mind’s eye, often after careful thought or engagement with the imagination. The definition of envision, which belongs in the group of words having to do with thought, holds nuances of meaning that reveal why artists envision the world, and the varying purposes their images serve. • What do these images communicate about an artist’s view of the world? • Can we, by example, look at our world in a new way, forming images that express a view of the world we inhabit? Envision: Form an Image of What Can’t Be Seen Over the centuries, artists have served the needs of both church and state, depicting unseen aspects of culture: values, the authority of rulers, and the stability of society. -

Adirondack Camps National Historic Landmarks Theme Study

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (June 1991) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ADIRONDACK CAMPS NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY B. Associated Historic Contexts THE ADIRONDACK CAMP IN AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE C. Form Prepared by name/title Wesley Haynes, Historic Preservation Consultant; James Jacobs, Historian, National Historic Program, National Park Service date March 28, 2000; updated organization 2007 street and number 22 Brightside Drive telephone 917-848-0572 city or town Stamford state Connecticut zip code 06902 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archaeology and Historic Preservation. (See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature and title of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

A Precancel Primer — III

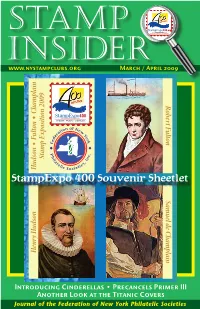

StampExpo400.org Stamp HUDSON • FULTON • CHAMPLAIN Insider www.nystampclubs.org March / April 2009 Robert Fulton Champlain StampExpo400 . HUDSON • FULTON • CHAMPLAIN n of N tio ew ra Y e o d r Fulton Fulton e k F . P . h c Stamp Exposition 2009 Exposition Stamp il n a I te s, lic tie Hudson Hudson Socie StampExpo 400 Souvenir Sheetlet Samuel de Champlain Samuel Henry Hudson Henry Introducing Cinderellas • Precancels Primer III Another Look at the Titanic Covers Journal of the Federation of New York Philatelic Societies Colorful… Historical UNITED STATES Commemorative Album Pages by Featuring illustrated display frames for singles of all commemoratives since the 1893 Columbians, this sectional album also has background stories that place the stamps in their historic perspective. And, to highlight the stamps, there’s a distinctively designed border with the multicolored pictorial illuminations that have become a White Ace trademark. There’s more to White Ace than meets the eye: the heavy album page card stock is acid-free — your assurance of long lasting freshness; and the looseleaf style provides flexibility, so the album can grow with your collec- tion. What’s more, with annual supplements it will always be up-to-date. Choose this White Ace album for your U.S. Commemorative Singles or one of its com- panion albums for blocks or plate blocks. Albums are also available for U.S. Regular Issues in all three formats. You will be opting for America’s superlative stamp albums. White Ace Albums are published by The Washington Press — makers of ArtCraft first day covers and StampMount brand mounts. -

September 1, 1914—August 31, 1915

CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Volume Seventeen LH 1 C3+ SEPTEMBER 1, 1914—AUGUST 31, 1915 Published weekly throughout the college year Monthly in July and August Forty issues and index to a volume ITHACA, NEW YORK a? 7 7984 - I lit VOL. XVII, No. 1 [PRICE TEN CENTS] SEPTEMBER 24, 1914 ITHACA, NEW YORK CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS The Farmers* Loan and INVESTMENT PROBLEMS atom £rfjmii far This is a time to scrutinize your investments Trust Company carefully and seek the best advice in connection An ENDOWED PREPARATORY SCHOOL 16, 18, 20, 22 William St., New York therewith. We have NOTHING TO SELL, but are in- Illustrated Boek 9» Branch 475 5th Ave. terested only in what will best meet the special requirements of each individual customer. Closing prices of all securities furnished on Ttans Sbdte B*r, Ph.D., Pirt Dtp«it, ij-kNTbrtv S 15 Cockspur St., S. W. request. LOMUUN I 2g ow Broad SUE c Send for our pamphlet PARIS 41 Boulevard Haussmanit SHIFTING of INVESTMENTS. BERLIN 56 Unter den Linden N. W. 7 The LETTERS OF CREDIT fHMIDT &(jALLATIN Mercersburg Academy FOREIGN EXCHANGE 111 BROADWAY, NEW YORK CITY i Members of the New York Stock Exchange PREPARES FOR ALL COLLEGES CABLE TRANSFERS CHAS. H. BLAIR '98 AND UNIVERSITIES : AIMS AT THOROUGH SCHOLARSHIP, Baker, Vawter & Wolf BROAD ATTAINMENTS AND N. W. HALSEY & CO. CHRISTIAN MANLINESS PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS Dealers in ADDRESS WILLIAM A. VAWTER WILLIAM A. VAWTER II ,'05 Municipal, Railroad and Public Utility WILLIAM MANN IRVINE, Ph. W. W. BUCHANAN GEORGE W. SWITZER President GEORGE D. WOLF MERCERSBURG. -

ADIRONDACK COLLECTION Mss

ADIRONDACK COLLECTION Mss. Coll. No. 32 1848- present. 5 linear feet History The Adirondack Mountains are a range of peaks in Northeastern New York State related geologically to the Appalachian Mountains to the south and the Laurentian range in Quebec to the north. The mountains consist of very ancient rock, about a billion years old, which has been uplifted into a “dome” over the last 5 million years or so. Human habitation of the Adirondack region is quite recent. Native tribes of Mohawk and Algonquin Indians hunted in the region, but did not settle there. The first Europeans explored the area in the mid 17th century. As settlement of the region began, the vast timber resources of the Adirondack forest were exploited for building materials and fuel. This exploitation continued for nearly 200 years as demand for wood for timber and land for farming and mining grew. By the mid 1800s, public appreciation for the remote Adirondack wilderness began to increase as writers and artists romanticized the region. Tourism increased as the concept of the “Great Camp” became popular. Larger numbers of city dwellers came as railroads made the region more accessible. By the late 19th century, concern over the depletion of the Adirondack’s resources resulted in calls for the region to be preserved “forever” as wild forest. In 1885, the Adirondack Forest Preserve was created and in 1892 the Adirondack Park was formally recognized and given the permanent protection of the New York State Constitution two years later, thanks to the pioneering work of conservationists like Verplanck Colvin and Seneca Ray Stoddard. -

Adirondack Chronology

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks Chronology Management Team Gary Chilson Professor of Environmental Studies Editor, The Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies Paul Smith’s College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 265 Paul Smiths, NY 12970-0265 [email protected] Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 20 January (No. 43) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. It is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks. It is hoped that it may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in-depth research. Can the ARL further serve your research needs? To find out, visit our web page, or even better, visit the ARL at the Center for the Forest Preserve, 897 St. David's Lane, Niskayuna, N.Y., 12309. The ARL houses one of the finest collections available of books and periodicals, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and private papers dealing with the Adirondacks. Its volunteers will gladly assist you in finding answers to your questions and locating materials and contacts for your research projects. Introduction Is a chronology of the Adirondacks really possible? -

Richard S Allen Collection Catalogue Inventory

Inventory of the Richard Sanders Allen Collection Box 1. Hand labeled: Iron Industry General Tahawus & “Mixed Iron.” (Published books and booklets are listed in bibliographic style; pamphlets are not described; organized research materials are listed separately.) Cohen, Linda, Sarah Cohen and Peg Masters. Old Forge: Gateway to the Adirondacks. Postcard History Series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003. Cottrell, Alden, T. The Story of Ringwood Manor. 6th ed. Trenton, NJ: Trenton Printing Co., Inc., 1954. Donald, WJA. The Canadian Iron and Steel Industry: A Study in the Economic History of a Protected Industry. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1915. DuFresne, Jim. Michigan State Parks: A Complete Recreation Guide. 2nd ed. Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1998. Eisenhuth, Chester F. Maltby’s Furnace and One Man’s Memories. NP: The North East Historical Society, 1996. Fennessy, Lana. The History of Newcomb. Newcomb, NY: By the Author, 1996. Ghee, Joyce C. and Joan Spence. Poughkeepsie: Halfway Up the Hudson. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1997; reprint 1998. Glenn, Morris F. The Story of Three Towns: Westport, Essex and Willsboro, New York. Alexandria, VA: By the Author, 1805 Sword Lane, Alexandria, Va.: 1977. Gordon, Robert B. A Landscape Transformed: The Ironmaking District of Salisbury, Connecticut. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. (Two copies) Greer, Edward. Big Steel: Black Politics and Corporate Power in Gary, Indiana. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979. Hawke, David Freeman. John D.: The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1980. Isleib, Charles R and Jack Chard. The West Point Foundry and the Parrott Gun: A Short History. -

AD Application Purpose AA Assignment of Authorization AM

AD Application Purpose AA Assignment of Authorization AM Amendment AR DE Annual Report AU Administrative Update CA Cancellation of License CB C Block Election DC Data Correction DU Duplicate License EX Request for Extension of Time HA HAC Report LC Cancel a Lease LE Extend Term of a Lease LL 603T, no longer used LM Modification of a Lease LN New Lease LT Transfer of Control of a Lessee LU Administrative Update of a Lease MD Modification NE New NT Required Notification RE DE Reportable Event RL Register Link/Location RM Renewal/Modification RO Renewal Only TC Transfer of Control WD Withdrawal of Application AD Application Status 1 Submitted 2 Pending AA Granted C Consented To D Dismissed E Eliminate G Granted H History Only I Inactive J HAC Submitted K Killed M Consummated N Granted in Part P Pending Pack Filing Q Accepted R Returned S Saved T Terminated U Unprocessable W Withdrawn XNA Y Application has problems AD Notification Code 1 First Buildout/Coverage Requirement 2 Second Buildout/Coverage Requirement 3 Third Buildout/Coverage Requirement 4 Fourth Buildout/Coverage Requirement A All coverage requirements (for those that have neither 5 or 10) C Consummation of transfer or assignment D Request regular authorization for facilities operating under developmental authority G Notification of compliance with yearly station commitments for licencees with approved extended implementation plans. H Final notification that construction requirements have been met for referenced system with approved extended implementation plans. S Construction