Adirondack Camps National Historic Landmarks Theme Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carnegie Camp on Raquette Lake

Volume 16, 10, Number Number 2 2 Winter 2007–20082001-2002 NewsNews letter North Point: The Carnegie Camp on Raquette Lake ADIRONDACK ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE The Carnegie Camp, North Point, Raquette Lake, c. 1905 (Rockefeller Family Collection) At the turn of the century, Raquette Lake, builder, and architect was unknown. Harvey one of the largest and most picturesque lakes Kaiser in his book Great Camps of the in the Adirondacks, was the site of several Adirondacks stated that, “The building plans large rustic camps designed by William West and execution of interior details suggest Durant. Less well known than Pine Knot and influences beyond the techniques of local Echo Camp is the Carnegie camp, designed craftsmen, although no record of the architect by Kirtland Kelsey Cutter and completed in exists.” Today its history, design, architect, 1903. and construction are thoroughly documented. Although the main buildings at Pine Knot Its history is as interesting as its architecture. and nearby Sagamore were influenced by The famous guide, Alvah Dunning, was the Swiss chalet architecture, the Carnegie camp first documented resident at North Point. He is more literally a Swiss chalet. There it settled here prior to 1865 and occupied a stands on the northern end of the lake, on a cabin originally built for hunters from slightly elevated plateau, commanding Albany. Another Albany resident, James Ten spectacular views. The land has been and still Eyck bought the land from the state after is known as North Point and the camp was Dunning issued him a quitclaim deed and built by Lucy Carnegie, the widow of constructed a modest hunting camp on the Andrew Carnegie’s younger brother Tom. -

Progress of Stream Measurements

Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 166 Series P, Hydrographic Progress Reports, 42 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOK REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1905 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1906 Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 166 Series P, HydwgrapMe Progress Reporte, 42 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DlKECTOK REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS THE CALENDAR YEAR 1905 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages » BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1906 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction......-...-...................___......_.....-.---...-----.-.-- 5 Organization and scope of work.........____...__...-...--....----------- 5 Definitions............................................................ 7 Explanation of tables...............................-..--...------.----- 8 Convenient equivalents.....-......._....____...'.--------.----.--------- 9 Field methods of measuring stream flow................................... 10 Office methods of computing run-off...................................... 14 Cooperation and acknowledgments................--..-...--..-.-....-..- 16 Hudson River drainage basin............................................... -

Camp Through the Decades. - Free Online Library

Camp through the decades. - Free Online Library He had a shake to his body, and it became more pronounced as he intoned in·tone  v. Cobb, age 92, reports that in the '30s as a young counselor, she was incensed that teenaged campers were required to continue to wear long black stockings while younger campers were allowed to wear socks. MoMullan (Alford Lake Camp) Maine Eliezer Melendez (Seventh Day Adventist) Puerto Rico Asher Melzer (D) (Camping Services, UJA UJA United Jewish Appeal UJA Union des Jeunes Avocats (French) UJA Universal Jet Aviation  Federation) New York Karen Meltzer (Brent Lake Camp) New York Robert (Dcc) Miller (D) (YMCA Camp Storer) Michigan Robert H. "Donald," I said diplomatically. "We would do some creative cooking, too. 373,019), 109 sq mi (282 sq km), SW Switzerland, surrounding the southwest tip of the Lake of Geneva. The population was 11,698 at the 2000 census.  Bonnie Brae brae  n.  and wedges of cheese that would not go bad for the day and make macaroni and cheese. The paintings depict Monet's flower garden at Giverny and were the main focus of Monet's artistic production during the last thirty years  that campers would gather in the bogs." The camp staff of today tread lightly on the land, teaching environmental awareness and recognizing their impact on nature. Alan Stolz tells of his purchase of Camp Cody in 1959. To recite in a singing tone. 2. Goldman (D) (Takajo) Maine Bryan "Skipper" Hall (D) (Sacramento Methodist Assembly Camp) New Mexico Libby Black Halpern (Pine Forest Camp, Timber Tops, Lake Owego Camp) Pennsylvania Ted S. -

990 P^ Return of Private Foundation

990_P^ Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O J 0 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation 7 Internal Revenue service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Pnr calendar year 2010 . or tax year beninninn . 2010. and endina . 20 G Check all that apply Initial return initial return of a former public charity Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION , INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see page 10 of the instructions) 235 EAST 42ND STREET (212) 733-4250 City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is ► pending, check here D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10017 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach H Check typet e of org X Section 501 ( c 3 exempt private foundation g computation , , . , . ► Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method . Cash X Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . ► of year (from Part ll, col (c), line ElOther (specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 16) 20 9, 30 7, 7 90. -

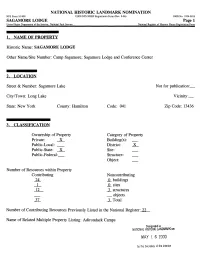

SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number: Camp Sagamore; Sagamore Lodge and Conference Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Sagamore Lake Not for publication:_ City/Town: Long Lake Vicinity:_ State: New York County: Hamilton Code: 041 Zip Code: 13436 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: __ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 24 0 buildings 1 0 sites 12 3 structures _ objects 37 3 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 22 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Adirondack Camps Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on MAY 1 6 2000 by the Secratary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

SUMMER 2019 NEWSLETTER Opening This Summer: ADKX Boathouse on Minnow Pond

THE EXCLUSIVE SUMMER GUIDE ISSUE! SUMMER 2019 NEWSLETTER Opening this summer: ADKX Boathouse on Minnow Pond. Enjoy a few hours on Minnow Pond from our new ADKX Boathouse. SUMMER 2019 PG 2 SUMMER 2019 PG 3 Two new exhibitions are sure to spark delight. Curious Creatures, a special—and quirky—exhibition features a monkey riding a goat, a school room filled with studious A WARM ADIRONDACK bunnies, smoking rabbits, and other unexpected examples WELCOME TO SUMMER 2019 of taxidermy such as a water FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DAVID KAHN AND bualo head and a python. All THE WHOLE TEAM AT ADKX are ornaments from Adirondack camps past and present. CURIOUS CREATURES Summer is here, and ADKX’s 2019 season o ers you and your family a wide range of exciting and uniquely Adirondack activities. Join us for a variety of new indoor and outdoor experiences for all ages! PRIVATE VIEWS Private Views, our other special Our new ADKX rustic boathouse opens on July 1, oering you exhibition for 2019, gives you the rare opportunity to cruise the waters of Minnow Pond in an the opportunity to see dozens antique guideboat, ski, or other Adirondack craft. And you can of iconic Adirondack landscape learn about the history of boating in the Adirondacks as you stroll paintings that are rarely if ever the scenic woodland trail leading from the ADKX campus publicly exhibited. to our boathouse. If you want to practice your rowing skills before heading out to the pond, our guideboat rowing interactive is available in our gigantic Life in the Adirondacks exhibition, along Rolling ‘Round the ‘Dacks is our new signature event on Saturday, August 17, with other fun hands-on activities. -

2009 Recreational Boating Report

New York State 2009 Recreational Boating Report New York State David A. Paterson, Governor Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation Carol Ash, Commissioner Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………….. 5 New Legislation for 2009………………………… 6 NYS Office of Parks Recreation & Historic Preservation Responsibilities…………. 7 New York Safe Boater Education Program………… 7 Public Vessels………………………………………. 7 Regulatory Permits………………………………….. 8 Vessel Theft…………………………………………. 8 Aids to Navigation…………………………………... 8 Publications and Public Outreach…………………… 9 Marine Law Enforcement………………………… 10 Marine Patrols………………………………………. 10 State Aid Program…………………………………... 10 Marine Law Enforcement Training…………………. 11 Statewide Activity Report…………………………... 12 Vessel Registrations……………………………………. 14 Registrations by Length, Hull and Power…………... 16 Accidents………………………………………….. 17 Summary 1980 to Present…………………………… 18 County and Waterway………………………………. 19 Types of Accidents…………………………………. 21 Operation at Time of Accident……………………… 22 Cause of Accident…………………………………... 24 Alcohol and Boating Accidents…………………….. 28 Month, Day and Time of Accidents………………… 29 Owner / Operator Data……………………………… 30 Type of Vessels…………………………………….. 33 Personal Watercraft Accidents……………………… 36 Recreational Boating Injuries………………………. 38 Recreational Boating Fatalities…………………….. 39 Introduction New York State has a long maritime history dating back to 1609 and the age of discovery. In 2009 New York celebrated the Quadricentennial anniversary of Henry Hudson’s sailing the Hudson River. In continuing with this tradition New York offers a wide variety of on water recreational activities from offshore sailing in the Atlantic Ocean and Long Island Sound to quiet paddles in picturesque Adirondack lakes. Boaters may also travel along the New York State Canal System connecting Eastern and Western New York by water. For these reasons it is easy to see why New York State is a leader in the number of vessels registered with almost 480,000 registered boats and many other vessels that do not require registration. -

Excursion to Climb Mt. Arab in the Adirondack Mountains Near Tupper Lake

TRIP B-3 EXCURSION TO CLIMB MT. ARAB IN THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS NEAR TUPPER LAKE William Kirchgasser, Department of Geology, SUNY Potsdam [email protected] INTRODUCTION The easily reached summit of Arab Mountain (Mt. Arab of trail guides), near Tupper Lake in southern St. Lawrence County, with its Fire Tower and open overlooks, offers spectacular panaramic views of the Adirondack Mountains. For geologists, naturalists and tourists of all ages and experiences, it is an accessible observatory for contemplating the geologic, biologic and cultural history of this vast wilderness exposure of the ancient crust of the North American continent. My connection to Mt. Arab began in the 1980s on the first of several hikes to the summit in the fall season with Elizabeth (Betsy) Northrop's third grade classes from Heuvelton Central School. Although the highways and waterways in these mountains can offer breathtaking vistas, to truly experience the expanse and quiet grandure ofthe Adirondacks, one must climb to a summit. At two miles roundtrip on a well-maintained trail and only 760 ft. (232 m) elevation change, Mt. Arab is ranked among the easiest of the fire tower trails in New York State (Freeman, 2001); at a leisurely pace the summit at 2545 ft (176m) elevation can be reached in thirty to forty-five minutes. Mt. Arab is included in many trail guides, among them one with many useful tips on hiking with children in the Adirondacks (Rivezzi and Trithart, 1997). Through the efforts of the Friends ofMt. Arab, the Fire Tower and Observer's Cabin have been restored and there are trail guides available at the trailhead. -

Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Pagel United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number: Camp Sagamore; Sagamore Lodge and Conference Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Sagamore Lake Not for publication: City/Town: Long Lake Vicinity:_ State: New York County: Hamilton Code: 041 Zip Code: 13436 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal:__ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 24 0 buildings 1 0 sites 12 3 structures _ objects 37 3 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 22 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Adirondack Camps Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on MAY 1 6 2000 by the Secratary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Waterways Waterways

ADIRONDACK WATERWAYS Scan this QR code with your smartphone to take our aerial tour! ADIRONDACK REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCIL VisitAdirondacks.com Adirondack Waterways Paddle the Waters of a Wilderness Like No Other There are more than 3,000 lakes and ponds and 6,000 miles of rivers and streams in the Adirondacks. Paddling ranges from roiling white- Adirondack Region Information Centers water chutes to glassy ponds where deer stop to drink; from a short circuit around a scenic lake to a multi-day river and lake trip. Regional Office of Sustainable This is a general guide to locations for paddling opportunities. Once you decide on a location, get yourself a good topographic There is no better place Tourism/Lake Placid CVB map and/or guidebook. Special usage regulations may apply along some routes, so refer to the appropriate Department of 518-523-2445 or 800-447-5224 Environmental Conservation publications or call them for specific information (see left). Much of the lands that border the routes to put GORE-TEX® gear www.lakeplacid.com identified in this guide are privately owned. State navigation law allows for paddlers to travel on private lands for short distances through its paces than amid [email protected] to bypass obstacles in the waterway. However, entering private lands for any other reason, including putting in and taking out, Lewis County Tourism is trespassing, unless permission has been granted from the landowner. If you lack experience or gear, knowledgeable guides and the trails and waterways 800-724-0242 www. outfitters will be happy to make your outing memorable. -

Men on the Mountain."

United States Department of Agriculture Men on the Forest Service Mountain Intermountain Region Ashley National Forest Ashley National Forest Vernal, Utah This story is dedicated to the personnel - - - past and present - of the Vernal Ranger District. - - Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest. - Eccl. 9:10 2 Preface "Hell is paved with good intentions," and the undertaking to write this history is a monument among them. At the onset, I fully intended to make this complete to the minutest detail and as flawless as human ability permits. Three things have thwarted these noble desires. 1. The preponderance of historical events and information in the area - mostly in the form of old-timers; 2. The scarcity of written information of the area and, worse yet, the unreliability and contradictory nature of what recorded history exists; 3. The necessity of completing this work in four months instead of the intended period of at least one year. Nevertheless, the history of District 2 is begun. Corrections will be needed in this text and should definitely be made. Omissions should be added and sketchy incidents enlarged upon. This responsibility will rest with those following me, but within these covers is the start of what could be a model for historical reports of other Ranger Districts in the Forest service. It was once said, "History is, indeed, little more than the register of the crises, follies and misfortunes of mankind." I say history is, indeed, little more than people. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Hyde Memorial State Park_________________________ Other names/site number: LA 136263_____________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: Historic and Architectural Resources of the New Deal in New Mexico, 1933-1942______ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 740 Hyde Park Road (NM 475)_________________________________ City or town: Santa Fe_____ State: NM_____ County: Santa Fe___ Zip Code 8750______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards