Southern Jewish History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

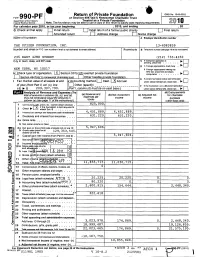

990 P^ Return of Private Foundation

990_P^ Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O J 0 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation 7 Internal Revenue service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Pnr calendar year 2010 . or tax year beninninn . 2010. and endina . 20 G Check all that apply Initial return initial return of a former public charity Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION , INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see page 10 of the instructions) 235 EAST 42ND STREET (212) 733-4250 City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is ► pending, check here D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10017 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach H Check typet e of org X Section 501 ( c 3 exempt private foundation g computation , , . , . ► Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method . Cash X Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . ► of year (from Part ll, col (c), line ElOther (specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 16) 20 9, 30 7, 7 90. -

The Upper Saranac Lake Association Mailboat March 2020 Coming Soon!!! Lynne Perry, Communications Chair the USLA Website Is Being Revised and Updated

The Upper Saranac Lake Association Mailboat March 2020 Coming Soon!!! Lynne Perry, Communications Chair The USLA website is being revised and updated. Since we first launched the website we have been fortunate to have an informative site that is used frequently. The new site will add some interactive capability while continuing to provide useful information as well as wonderful pic- tures. The format has changed. To introduce the website we have included a video to help you acquaint yourselves with the various sections of the site. I want to recognize the work of three USLA members who have spent many hours setting up the new site. Sara Sheldon- webmaster, Susan Hearn- President, and Liz Evans- video and technical advisor, have worked tirelessly to bring us the website. Watch for an email announcing the launch of the new website. Coming Soon! Trespassers on Your Premises? by Larry Nashett The morning’s walk to secretive individual. I’ve seen her tracks around here before, but the mailbox on January 14th rarely catch a glimpse of her. She seems to have purpose in her gait revealed we had not been and to be in a hurry. Although her feet are quite small, she has a alone overnight! In fact, it big stride. She didn’t dawdle, but rather stepped in her own prints, was clear that there had been making a very straight line of tracks across the driveway and up multiple trespassers on our the hill. property. We live on the lake Near the top of our driveway I found yet another interloper 1 year-round, and I can attest had been roaming the neighborhood. -

Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 Iii Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959

Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 iii Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 A Forty Years’ Crisis? Edited by Matthew Frank and Jessica Reinisch Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2017 © Matthew Frank, Jessica Reinisch and Contributors, 2017 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-8562-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-8564-6 eBook: 978-1-4725-8563-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Cover image © LAPI/Roger Viollet/Getty Images Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the -

2020) | Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

PINTO MUCENSKI HOOPER VANHOUSE & CO. 42 MARKET STREET, P.O. BOX 109 POTSDAM, NY 13676-0109 ADIRONDACK FOUNDATION P.O. BOX 288 LAKE PLACID, NY 12946 !129468! 926340 04-01-19 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2019 (Rev. January 2020) | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2019 calendar year, or tax year beginning JUL 1, 2019 and ending JUN 30, 2020 B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable: Address change ADIRONDACK FOUNDATION Name change Doing business as 16-1535724 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Final return/ P.O. BOX 288 518-523-9904 termin- ated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code G Gross receipts $ 43,457,539. Amended return LAKE PLACID, NY 12946 H(a) Is this a group return Applica- tion F Name and address of principal officer:RICH KROES for subordinates? ~~ Yes X No pending SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )§ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. -

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46 BY ALLEN W. PASCHAL On 7 December 1941 , the day that would "live in infamy," the United States became directly involved in World War II. Many events and deeds, heroic or not, have been preserved as historic reminders of that presence in the world conflict. The imprisonment of American sol diers captured in combat was a postwar curiosity to many Americans. Their survival, living conditions, and treatment by the Germans became major considerations in intensive and highly publicized investigations. However, the issue of German prisoners of war (POWs) interned within the United States has been consistently overlooked. The internment centers for the POWs were located throughout the United States, with different criteria determining the locations of the camps. The first camps were extensions of large military bases where security was more easily accomplished. When the German prisoners proved to be more docile than originally believed, the camps were moved to new locations . The need for laborers most specifically dic tated the locations of the camps. The manpower that was available for needs other than the armed forces and the war industries was insuffi cient, and Colorado, in particular, had a large agricultural industry that desperately needed workers. German prisoners filled this void. There were forty-eight POW camps in Colorado between 1943 and 1946.1 Three of these were major base camps, capable of handling large numbers of prisoners. The remaining forty-five were agricultural or other work-related camps . The major base camps in Colorado were at Colorado Springs, Trinidad, and Greeley. -

Remsen-Lake Placid Travel Corridor

Remsen-Lake Placid Travel Corridor Proposed Final Historic Preservation Plan for Implementation of Alternative 7 of the 2020 Remsen-Lake Placid Travel Corridor Unit Management Plan Amendment/Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION 625 Broadway, Albany NY 12233 NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 50 Wolf Road, Albany, NY 12232 www.dec.ny.gov March 2020 This page intentionally left blank. Appendix D: Historic Preservation Plan Executive Summary The Remsen-Lake Placid Travel Corridor (Corridor) is a transportation corridor 119 miles in length and owned by the people of the State of New York. It encompasses an historic rail line in the Adirondack Park and is managed by the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) in accordance with the 1996 Remsen-Lake Placid Travel Corridor Unit Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement (1996 UMP/EIS). This document has been prepared as a companion document for the 2020 Unit Management Plan Amendment/ Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (2020 UMP Amendment/SEIS) from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and NYSDOT. The State has proposed in the 2020 UMP Amendment/SEIS to: 1) rehabilitate 45 miles of the Corridor between Big Moose and Tupper Lake for contiguous rail service between Remsen and Tupper Lake, and 2) develop a 34-mile long segment of the Corridor, between Tupper Lake and Lake Placid, as a multi-use, all-season recreational trail for people of all abilities. The rail trail will connect the outdoor recreation-oriented communities of the Tri- Lakes area (Lake Placid, Saranac Lake and Tupper Lake) in the Adirondack Park. -

Inc. Chronology Management Team Carl

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of Protect the Adirondacks! Inc. Chronology Management Team Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard E. Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Abbie Verner Archivist, Town of Long Lake P.O. Box 42 Long Lake, NY 12847 [email protected] Frank M. Wicks Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 25 March 2012 (No. 63) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Chronology 1 last revised 3/26/2012 Contents Page Adirondack Research Library 2 Introduction 2 Key References 4 Bibliography and Chronology 18 Special Acknowledgements 19 Abbreviations, Acronyms and Definitions 22 Adirondack Chronology – Event and Year 36 Needed dates 388 Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. This useful reference is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) committee of Protect the Adirondacks! Inc., most recently via the Schaffer Library of Union College, Schenectady, NY where the Adirondack Research Library has recently been placed on ‘permanent loan’ by PROTECT. Union College Schaffer Library makes the Adirondack Research Library collections available to the public as they has always been by appointment only (we are a non-lending ‘special research library’ in the grand scheme of things. See http://libguides.union.edu/content.php?pid=309126&sid=2531789. Our holdings can be searched It is hoped that the Adirondack Chronology may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in- depth research. -

MATTERS WINTER NEWSLETTER 2019 VOLUME 28 NUMBER 1 a Public Architect: the Architecture of Alvin Walter Inman

AARCH MATTERS WINTER NEWSLETTER 2019 VOLUME 28 NUMBER 1 A Public Architect: The Architecture of Alvin Walter Inman private residences, and additions to commercial buildings. Many of his buildings remain a testament to the work of this truly public Alvin Inman is one of the most important architect, who combined richly regional architects that you’ve never heard detailed designs with modern of, despite the very public presence of his functionality. work across the northeastern Adirondacks. Although his name is not well-known today, Alvin Walter Inman was born on his work was celebrated in his time. In a February 26, 1895 to Ida and Plattsburgh Daily Republican piece about Curtis E. Inman, a Plattsburgh Alvin Inman stands in front of his Plattsburgh home alongside his John Russell Pope, the designer of banker, city supervisor, and wife, Vera (center), and Ida Eldredge. Courtesy of David Merkel. Plattsburgh’s City Hall and McDonough treasurer or director to several Monument , a guest commentator lauded local organizations and businesses. Alvin connections, including that his father served Inman’s work by saying he was “a graduated from Plattsburgh High School as a Champlain Valley Hospital director. A Plattsburgh designer whose creative faculties and then attended the University of Plattsburgh Sentinel article from 1924 and rare productive talents have been too Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts. His time reported that the firm’s pedigree in hospital little recognized or praised.” We agree. at college was interrupted while he served design meant that “plans and specifications for eight months in France during World will be of the best” for the $100,000 project. -

National Endowment for the Humanities Grant Awards and Offers, December 2010

OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS 1100 PENNSYLVANIA AVE., NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20506 (202)606-8446 WWW.NEH.GOV NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES GRANT AWARDS AND OFFERS, DECEMBER 2010 Note: Projects that are part of the We the People program, which encourages and strengthens the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture, are denoted by an asterisk. ALABAMA (2) $12,000 Birmingham Birmingham Museum of Art Outright: $6,000 [Preservation Assistance Grants] Project Director: Melissa Mercurio Project Title: Rehousing of the Buten Wedgwood Collection Project Description: Purchase of storage equipment to rehouse the Buten Wedgwood Collection, which consists of almost 8,000 pieces of ceramics dating from the inception of the Wedgwood Company in 1759 through the 1980s. Harry and Nettie Buten began collecting Wedgwood in 1931 and opened their museum in Merion, Pennsylvania, to the public in 1957. The collection, which includes some of the most unique Wedgwood wares, was acquired by the Birmingham Museum of Art in 2008, a gift from the Buten family through the Wedgwood Society of New York. Montevallo University of Montevallo Outright: $6,000 [Preservation Assistance Grants] Project Director: Carey Heatherly Project Title: Continued Improvement of the University of Montevallo's University Archives and Special Collections Project Description: The purchase of preservation supplies to provide better care for the Carmichael Library's archives and special collections, documenting the history of the university and women's education in Alabama. The archive includes a collection of dolls created by the Works Progress Administration's Alabama Visual Education Project and the Olmstead Brothers' original design for the campus, a designated National Historic District. -

Aaslh 2017 Annual Meeting Onsite Guide

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History ONSITE GUIDE AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S CONTENTS A N 3 Welcome from the Host Chairs EXHIBIT HALL SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS A 5 Welcome from the Program Chair 16 Exhibit Hall Highlights & Maps 32 Thursday, September 7 C I 6 Meeting Highlights 17 Exhibitors List 38 Friday, September 8 R 6 Need to Know and Updates 26 Austin Tours 44 Saturday, September 9 E 9 Featured Speakers 29 Evening & Special Events M 11 Sponsors 47 AASLH Institutional Partners PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS A 12 Schedule at a Glance and Patrons 30 Wednesday, September 6 49 Special Thanks WelcomeWelcometo AASLH 2017 veryone who attends is taking part in this conference. E Especially this year, given our theme. For me the conference theme, I AM History, reflects the role of individuals, singular decisions, and unique, consequential events that, large and very small, make up the many threads of history. You will see there is much on this I AM History program that speaks to the idea that relevant history is inclusive history. And all of us will experience Austin’s own breadth of people and culture in the tours, evening and offsite events, the new “Texas Track” of sessions, and in our own wanderings around town. Program Committee Chair Dina Bailey and Host Committee Co-chairs Laura Casey and Margaret Koch coordinated hours of toil by their committees to create this adventurous program. -

September 22, 2017 the Honorable Orrin Hatch the Honorable Ron Wyden SH-104 Hart Senate Office Building SD-221 Dirksen Senate

September 22, 2017 The Honorable Orrin Hatch The Honorable Ron Wyden SH-104 Hart Senate Office Building SD-221 Dirksen Senate Office Building United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Kevin Brady The Honorable Richard Neal 1011 Longworth House Office Building 341 Cannon House Office Building United States House of Representatives United States House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairman Hatch, Ranking Member Wyden, Chairman Brady and Ranking Member Neal: On behalf of the undersigned businesses and organizations that strive to strengthen our nation’s economy by preserving its rich history, we ask that you retain and enhance the historic tax credit as Congress develops legislation to reform the tax code. We strongly support the successful and longstanding federal policy of incentivizing the rehabilitation of our historic buildings. Incorporated into the tax code more than 35 years ago, the historic tax credit (HTC) is a widely- used redevelopment tool for underutilized properties, from inner cities to small towns across the country. The credit is the most significant investment the federal government makes to preserve our nation's historic properties. Since 1981 the credit has leveraged more than $131 billion in private investment, created more than 2.4 million jobs, and adapted more than 42,000 historic buildings for new and productive uses. Over 40 percent of HTC projects financed in the last fifteen years are in communities with populations of less than 25,000. President Ronald Reagan praised the incentive in 1984, stating, "Our historic tax credits have made the preservation of our older buildings not only a matter of respect for beauty and history, but of course for economic good sense." Over the life of this federal initiative, the IRS has issued $25.2 billion in tax credits while generating more than $29.8 billion in direct federal tax revenue. -

Village of Saranac Lake North Country Regional Economic Development Council Downtown Revitalization Initiative Strategic Investment Plan

Village of Saranac Lake North Country Regional Economic Development Council Downtown Revitalization Initiative Strategic Investment Plan march 2019 village of sarananc Lake downtown revitalization initiative Local Planning Committee Members Hon. Clyde Rabideau, Co-Chair Amy Cantania Carl Hagmann* Mayor Executive Director Owner/Broker Village of Saranac Lake Historic Saranac Lake Say Real Estate James McKenna, Co-Chair Sarah Clarkin Adam Harris Co-Chair Executive Director Owner North Country REDC Harrietstown Housing Authority Grizle T’s Stacy Allott Jeremy Evans Chris Night President CEO Communications Director Geomatics Land Surveying Franklin County IDA North Country Community College Tom Boothe Kate Fish Russ Kinyon Chair Executive Director Director of Economic Development Saranac Lake Development Board Adirondack North Country Association Franklin County Economic Development Office Carolyn Bordonaro Tim Fortune Shannon Oborne Director of Sales Chair Chief Marketing Officer Hotel Saranac Downtown Advisory Board Paul Smith’s College Kelly Brunette Sylvia Getman Matt Scollin Marketing Manager CEO Director of Communications ROOST Adirondack Health Adirondack Health Jason Smith Vice Chair Parks and Trails Advisory Board Special thanks to the Village of Saranac Lake staff and State Partners Village State Jamie Konkoski*, Community Development Director Barbara Kendall, Coastal Resources Specialist, Department of State Paul VanCott*, Village Board of Trustees Stephen Hunt, Regional Director, North Country Office, Empire State Development John Sweeney*, Village Manager Crystal Loffler, Vice President, State Programs, NYS Homes and Community Renewal Paul Blaine*, Development Code Administrator Seth Belt, Regional Representative, North Country, Governor’s Office *Non-voting LPC Member This document was developed by the Village of Saranac Lake Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State and NYS Homes and Community Renewal.