I Don't Need Your Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socialist Planning

Socialist Planning Socialist planning played an enormous role in the economic and political history of the twentieth century. Beginning in the USSR it spread round the world. It influenced economic institutions and economic policy in countries as varied as Bulgaria, USA, China, Japan, India, Poland and France. How did it work? What were its weaknesses and strengths? What is its legacy for the twenty-first century? Now in its third edition, this textbook is fully updated to cover the findings of the period since the collapse of the USSR. It provides an overview of socialist planning, explains the underlying theory and its limitations, looks at its implementation in various sectors of the economy, and places developments in their historical context. A new chap- ter analyses how planning worked in the defence–industry complex. This book is an ideal text for undergraduate and graduate students taking courses in comparative economic systems and twentieth-century economic history. michael ellman is Emeritus Professor in the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He is the author, co- author and editor of numerous books and articles on the Soviet and Russian economies, on transition economics, and on Soviet economic and political history. In 1998, he was awarded the Kondratieff prize for his ‘contributions to the development of the social sciences’. Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 128.122.253.212 on Sat Jan 10 18:08:28 GMT 2015. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139871341 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2015 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 128.122.253.212 on Sat Jan 10 18:08:28 GMT 2015. -

Heretics of China. the Psychology of Mao and Deng

HERETICS OF CHINA HERETICS OF CHINA THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MAO AND DENG NABIL ALSABAH URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-445061 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20378/irbo-44506 Copyright © 2019 by Nabil Alsabah Cover design by Katrin Krause Cover illustration by Daiquiri/Shutterstock.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. ISBN: 978-1-69157-995-2 Created with Vellum During his years in power, Mao Zedong initiated three policies which could be described as radical departures from Soviet and Chinese Communist practice: the Hundred Flowers of 1956-1957, the Great Leap Forward 1958-1960, and the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Each was a disaster: the first for the intellectuals, the second for the people, the third for the Party, all three for the country. — RODERICK MACFARQUHAR, THE SECRET SPEECHES OF CHAIRMAN MAO In many ways, [Deng Xiaoping’s] reputation is underestimated: while Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev oversaw the peaceful end of Soviet communist rule and the dismembering of the Soviet empire, he had wanted to keep the Soviet Union in place and reform it. Instead it fell apart; communism lost power—and Russia endured a decade of instability […]. Perhaps the most influential political titan of the late 20th century, Deng succeeded in guiding China towards his vision where his fellow communist leaders failed. — SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE, TITANS OF HISTORY CONTENTS Introduction ix 1. -

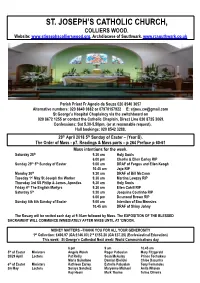

Easter 28 and 29Th, April

: ST. JOSEPH’S CATHOLIC CHURCH, COLLIERS WOOD. Website: www.stjosephscollierswood.org. Archdiocese of Southwark. www.rcsouthwark.co.uk ! Parish Priest Fr Agnelo de Souza 020 8540 3057 Alternative numbers: 020 8640 0882 or 07970157922 E: [email protected] St George’s Hospital Chaplaincy via the switchboard on 020 8672 1255 or contact the Catholic Chaplain, Direct Line 020 8725 3069. Confessions: Sat 5.30-5.50pm. (or at reasonable request). Hall bookings: 020 8542 3288. 29th April 2018 5th Sunday of Easter – (Year B). The Order of Mass - p7. Readings & Mass parts – p 264 Preface p 60-61 Mass intentions for the week. Saturday 28th 9.30 am Holy Souls 6.00 pm Charlie & Ellen Earley RIP Sunday 29th 5th Sunday of Easter 9.00 am DRAF of Fergus and Ellen Keogh 10.45 am Jojo RIP Monday 30th 9.30 am DRAF of Bill McCann Tuesday 1st May St Joseph the Worker 9.30 am Martina Lewzey RIP Thursday 3rd SS Philip & James, Apostles 9,30 am Holy Souls Friday 4th The English Martyrs 9.30 am Ellen Cahill RIP Saturday 5th 9.30 am Joaquina Coutinho RIP 6.00 pm Desmond Brown RIP Sunday 6th 6th Sunday of Easter 9.00 am Intention of Ena Menezes 10.45 am DRAF of Shiny Johny The Rosary will be recited each day at 9.10am followed by Mass. The EXPOSITION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT WILL COMMENCE IMMEDIATELY AFTER MASS UNTIL AT 12NOON. MONEY MATTERS –THANK YOU FOR ALL YOUR GENEROSITY 1st Collection: £400.97 (GA £146.00) 2nd £153.20 (GA £37.25) (Ecclesiastical Education) This week: St George’s Cathedral Next week: World Communications day 6 pm 9 am 10.45 am 5th of Easter Ministers Angela Walsh Roger Pabualan Mary Fitzgerald 28/29 April Lectors Pat Reilly Sean McAuley Prince Tochukwu Maria Guindano Damian Bielicki Chloe Dacunha 6th of Easter Ministers Kathleen Earley Estrella Pabualan Tony Fernandes 5/6 May Lectors Soraya Sanchez Maryanne Michael Anita Whelan Ray Hearn Mark Thorne Telma Oliveira : THE POWER OF AMEN. -

TODAY IS the END of the SEASON of CHRISTMAS PRIEST's CHRISTMAS OFFERING Fr. Agnelo Extends His Gratitude for the Christmas Of

ST JOSEPH'S CATHOLIC CHURCH 63 High Street, Colliers Wood, London, SW19 2JF - Parish Office Tel No 020 8542 8082 - Email: [email protected] All correspondence to The Presbytery: 30 Park Road, Colliers Wood, London, SWl9 2HS - Tel No. 020 8540 3057 Parish Priest Fr Agnelo de Souza 020 8540 3057 Parish Secretary : 07970157922 E: [email protected] Safeguarding Contacts; Mobile number 07485189950 Helen McHugh email; [email protected] Vincent Bolt email; [email protected] St George’s Hospital Chaplaincy via the switchboard on 020 8672 1255 or contact the Catholic Chaplain, Direct Line 020 8725 3069. Email: [email protected] . Confessions: Sat 5.30-5.50pm. (or at reasonable request). Hall bookings: 020 8542 3288(suspended)Web address www.stjosephscollierswood.co.uk SUNDAY THE BAPTISM OF THE LORD. FROM MONDAY 1ST. WEEK IN ORDINARY TIME Saturday 9th. January Mass 6.00pm Mary Fitzgerald Birthday Sunday 10th. January Mass 9.00am Intentions of Fergus and Ellen Keogh Sunday 10th. January Mass10.45am George Fernandes RIP Monday 11th. January Mass 9.30am Intentions of Martina McGill Tuesday 12th. January Mass 9.30am. Wednesday 13th. January CHURCH CLOSED Thursday 14th. January Mass 9.30am Friday 15th. January Mass 9.30am Saturday 16th. January Mass 6pm Simon Akygina & Monica Gali Sunday 17th. January Mass 9.00am Santo Nino Celebration. (Roger Pabualan) Sunday 17th. January Mass 10.45am Cyprian A Rozario RIP PLEASE DO NOT VENTURE ONTO THE ALTAR. ALL WHO DO SO MAY BE ASKED TO LEAVE THE CHURCH. TODAY IS THE END OF THE SEASON OF CHRISTMAS PRIEST’S CHRISTMAS OFFERING Fr. -

2008 Payroll Information

Health Gross Pension Insurance Life Insurance Additional Pay* Termination Date (longevity Fire LastName FirstName Department Position Title Earnings Benefit Benefit Benefit Medicare Social Security Work Comp See Addendum 1 Police Longevity and add pay pro‐rated) Longevity GRADY SYLVIA BOARDS & COMMIS/BOARDS &P.T. ARTS CENTER COORD (I) 23,524.40 341.10 1,458.51 575.94 MASTERSON DAVID BUILDING MAINT/G P.T. CUSTODIAN (UNION) 15,718.89 1,642.60 60.00 228.79 978.30 404.04 MUMME REX BUILDING MAINT/G BUILDING MAINTENANCE TECHNICIA 65,227.02 6,816.24 5,544.16 88.20 944.53 4,038.69 1,670.61 LAGUNA ANDRZEJ BUILDING MAINT/G P.T. CUSTODIAN (UNION) 11,845.00 171.74 734.49 304.39 ROSS ROBERT BUILDING MAINT/G P.T. CUSTODIAN (UNION) 10,539.87 1,101.45 60.00 153.71 657.19 274.46 GRAFF IRENE BUILDING MAINT/G BUILDING MAINT. CLERK TYPIST 38,952.69 4,070.56 16,920.90 88.20 564.78 2,415.04 1,440.36 VALDIVIA MIGUEL BUILDING MAINT/G P.T. CUSTODIAN (UNION) 12,358.17 1,291.48 60.00 180.07 769.94 312.50 JOHNSON GEORGE BUILDING MAINT/G BUILDING MAINTENANCE TECHNICIA 58,202.53 6,082.13 3,200.26 88.20 842.19 3,601.23 1,486.49 SCHROEDER JOHN BUILDING MAINT/G ASST. BUILDING MAINT. SUPT. 71,061.38 7,425.86 5,544.16 181.44 1,020.94 4,365.43 1,829.12 GARNICA MOISES BUILDING MAINT/G P.T. -

Válido Até: 20/10/2011 Administrador De Edifícios

Válido até: 20/10/2011 Administrador de Edifícios - ADEM - Macaé (Ampla Concorrência) Classif Inscrição Nome Situação 1 1076620 CAIO PONTES GONCALVES Convocado 2 1070126 JOCEMAR FRANCISCO TAVARES DA ROCHA JUNIOR Convocado 3 1280295 GLAUBE GLAUCO DE P. P. SANTOS Convocado 4 1306391 FABIO DO NASCIMENTO PORTO Convocado 5 1003755 JOSAFA SEVERINO GUIMARAES DA SILVA Convocado 6 1141775 JOAO CARLOS CANDIDO MACHADO Desistente 7 1067427 LEIB PAULO DE MORAES ROICHMAN Convocado 8 1108646 ELIAS COSTA E SILVA Em espera 9 1014374 FABIO SOLEMAN PEREIRA Em espera 10 1154052 LUCIANO DOS SANTOS MELO Em espera 11 1121413 EDLENE JOSE DA SILVA Em espera 12 1226550 LUIZ CARLOS RODRIGUES SOARES Em espera 13 1333046 MARCO ANTONIO VIEIRA DE SOUSA Em espera 14 1076442 ANDERSON MANHAES SILVA Em espera 15 1293788 LUIZ CARLOS ANTUNES SANTOS Em espera 16 1228560 DAVI COUTINHO MAIA Em espera 17 1288431 ROSANA DA SILVA SA FREIRE Em espera 18 1147218 CLARISSA LOUISE DE SOUZA LAPA DOS SANTOS Em espera 19 1230964 VINICIUS SOARES FERNANDES DE FREITAS Em espera 20 1089471 JORGE LUIZ LONTRA CARDOZO Em espera 21 1062840 RODRIGO CESAR DE SOUSA Em espera 22 1291742 RAFAEL BARBOSA FERREIRA Em espera Válido até: 20/10/2011 Administrador de Edifícios - ADER - Rio de Janeiro (Ampla Concorrência) Classif Inscrição Nome Situação 1 1104721 ALEXANDRE DA FONSECA TAVARES VITORINO Convocado 2 1250388 VICTOR HUGO VAZ DE CARVALHO DOS SANTOS Convocado 3 1303244 CARLOS ALBERTO REI SOARES Convocado Válido até: 20/10/2011 Administrador de Edifícios - ADER - Rio de Janeiro (Ampla Concorrência) -

Dialogue of Cultures and Partnership of Civilizations

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF EDUCATION ST. PETERSBURG INTELLIGENTSIA CONGRESS ST. PETERSBURG UNIVERSITY OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES under the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia DIALOGUE OF CULTURES AND PARTNERSHIP OF CIVILIZATIONS May 15–20, 2014 The Conference is held in accordance with The conference, originally called ‘The Days of Sci - the Decree of President of Russia V. V. Putin en ce in St. Petersburg University of the Humanities ‘On perpetuating the memory and Social Sciences’ is the 22nd in number of Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov’ and the 14th in the status of the International No 587, dated from May 23, 2001 Likhachov Scientific Conference To implement the project ‘The 14th International Likhachov Scientific Conference’ state funds are used. The funds are allocated as a grant in accordance with the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of March 29, 2013 No 115–rp and the tender held by the Association “Znaniye” of Russia St. Petersburg 2014 ББК 72 Д44 Scientifi c editor A. S. Zapesotsky, Chairman of the Organizing Committee of the International Likhachov Scientifi c Conference, corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Dr. Sc. (Cultural Studies), Professor, Scientist Emeritus of the Russian Federation, Artist Emeritus of the Russian Federation Recommended to be published by the Editorial and Publishing Council of St. Petersburg University of the Humanities and Social Sciences Dialogue of Cultures and Partnership of Civilizations: the 14th Inter national Д44 Likha chov Scientifi c Conference, May 15–20, 2014. St. Peters burg : SPbUHSS, 2014. — 174 p., il. ISBN 978-5-7621-0792-1 In the collection there were materials of the 14th Likhachov’s International Scientifi c Readings published, it was held on May 15–20, 2014 in SPbUHSS in accordance with the Decree of the Presi- dent of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin “On perpetuating the memory of Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov”. -

Parliament Rsa Joint Committee on Ethics And

PARLIAMENT RSA JOINT COMMITTEE ON ETHICS AND MEMBERS' INTERESTS REGISTER OF MEMBERS' INTERESTS 2013 Abrahams, Beverley Lynnette ((DA-NCOP)) 1. SHARES AND OTHER FINANCIAL INTERESTS No Nature Nominal Value Name of Company 100 R1 000 Telkom 100 R2 000 Vodacom 2. REMUNERATED EMPLOYMENT OUTSIDE PARLIAMENT Nothing to disclose. 3. DIRECTORSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS Directorship/Partnership Type of Business Klip Eldo's Arts Arts 4. CONSULTANCIES OR RETAINERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 5. SPONSORSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 6. GIFTS AND HOSPITALITY Nothing to disclose. 7. BENEFITS Nothing to disclose. 8. TRAVEL Nothing to disclose. 9. LAND AND PROPERTY Description Location Extent House Eldorado Park Normal House Eldorado Park Normal 10. PENSIONS Nothing to disclose. Abram, Salamuddi (ANC) 1. SHARES AND OTHER FINANCIAL INTERESTS No Nature Nominal Value Name of Company 2 008 Ordinary Sanlam 1 300 " Old Mutual 20 PLC Investec Unit Trusts R47 255.08 Stanlib Unit Trusts R37 133.56 Nedbank Member Interest R36 898 Vrystaat Ko -operasie Shares R40 000 MTN Zakhele 11 Ordinary Investec 2. REMUNERATED EMPLOYMENT OUTSIDE PARLIAMENT Nothing to disclose. 3. DIRECTORSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 4. CONSULTANCIES OR RETAINERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 5. SPONSORSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 6. GIFTS AND HOSPITALITY Nothing to disclose. 7. BENEFITS Nothing to disclose. 8. TRAVEL Nothing to disclose. 9. LAND AND PROPERTY Description Location Extent Erf 7295 Benoni +-941sq.m . Ptn 4, East Anglia Frankfurt 192,7224ha Unit 5 Village View Magaliessig 179sq.m. Holding 121 RAH 50% Int. in CC Benoni +-1,6ha Stand 20/25 Sandton 542sq.m. Unit 21 Benoni 55sq.m. Erf 2409 Benoni 1 190sq.m. -

Karen Keslen Kremes.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE PONTA GROSSA SETOR DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA KAREN KESLEN KREMES CULTURA GEEK E TECNOLOGIA: REFLEXÕES SOBRE OS HÍBRIDOS DE VIDEOGAME E CINEMA INTERATIVO PONTA GROSSA 2018 KAREN KESLEN KREMES CULTURA GEEK E TECNOLOGIA: REFLEXÕES SOBRE OS HÍBRIDOS DE VIDEOGAME E CINEMA INTERATIVO Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do título de Mestre em História na Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Área de História, Cultura e Identidades. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Patrícia Camera Varella PONTA GROSSA 2018 Dedico a Deus. A Ele toda honra. Para sempre. AGRADECIMENTOS Palavras jamais poderão expressar toda minha inteira gratidão à Aquele que é o primeiro lugar em minha vida: Deus. Muito obrigada, Senhor, por me dar forças, coragem e capacidade para cursar o mestrado. Tudo isto faz parte do Seu caminho e dos planos que o Senhor tem para minha vida. Agradeço eternamente por esta oportunidade e que eu possa usar todo esse conhecimento com sabedoria. Obrigada a família maravilhosa que tenho ao meu lado. Pessoas essenciais que me deram ânimo todos os dias através de conselhos com bom-humor e me acompanharam nesta longa caminhada. Vocês são demais! Obrigada as boas pessoas que Deus colocou em meu caminho. Professores, funcionários e amigos que estão ao meu lado desde minha graduação. Obrigada pela amizade e gentileza, vocês são uma benção para mim e jamais esquecerei esses anos de trabalho e diversão que passei junto de vocês. Obrigada a minha orientadora pela paciência e colaboração. Foram muitos percalços ao longo deste caminho, mas essa investigação não seria realidade sem sua ajuda. Obrigada aos professores da minha banca de qualificação e de defesa por disponibilizarem de seu tempo para contribuir com essa pesquisa e por acreditarem neste tema como parte integrante da historiografia. -

Fr. Romeu Godinho

God has bestowed a Golden Occasion upon the Diocesan Catechetical Centre Fr. Romeu Godinho The Diocesan Catechetical Centre is celebrating the 50th year of its birth. God has bestowed upon us a Golden Occasion. We thank God for all the beautiful work of faith formation done during these 50 years in our parishes and schools, and for all the blessings received from God. The formal inauguration of the jubilee year was done with the celebration of a solemn Eucharist on 3rd June, 2018, at the Basilica of Bom Jesus, Old Goa. The inaugural was held at the Basilica because St. Francis Xavier is the Patron Saint of the Diocesan Catechetical Centre. The Holy Eucharist was presided over by Rev. Fr. Almir de Souza. Fr. Almir was one of the members of the first diocesan Catechetical Committee. The Diocesan Catechetical Centre was established by the then Apostolic Administrator of the Archdiocese of Goa, Daman and Diu, Msgr. Francisco Xavier da Piedade Rebello, who through a Decree dated 7th March, 1969, substituted it for the Secretariat of the Christian Doctrine which was established on 25th September, 1952. Christianity in Goa: Though the Christian faith was brought to India in the first century by the Apostle St. Thomas, and probably also by St. Bartholomeu,1 the glorious chapter of the expansion of the Catholic Church in the East can be said to have begun after the European discovery of the sea route to India in 1498. This helped the advent of the European missionaries to these lands,2 one of them being St. -

Knowing Fr Agnelo

Messages Of Support Collection of Letters and Messages received from supporters. May it be an inspiration to us all to continue in our Prayers and Work towards the Beatification Process Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 1 Dear Friends of the Venerable Fr. Agnelo, I would like first of all to congratulate you on this important milestone in your history - the silver jubilee of your foundation. It is wonderful to see how the association has grown and developed over the last twenty five years. Secondly, I would like to thank all of you for all the great work you have done in our parishes here in London helping people be aware of the great witness to Christ that Fr. Agnelo gave in his life and the various ways you have embodied his spirit of prayer, penance and good works. Finally, I join with in thanking god for the gift of Fr. Agnelo's unstinting devotion to Christ and the Church. He continues to be an inspiration to all of us. With every good wish and blessing, + Bishop Patrick Lynch SS.CC. Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 2 Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 3 A Message from Bishop Howard Tripp On the occasion of the Silver Jubilee of the Founding in the United Kingdom of the Association of the Friends of the Venerable Father Agnelo SFX I send my greetings to the members of the Association of the Friends of the Venerable Father Agnelo established here in the United Kingdom twenty five years ago. -

ST JOSEPH News Letter 23Rd. May 2021

ST JOSEPH'S CATHOLIC CHURCH 63 High Street, Colliers Wood, London, SW19 2JF - Parish Office Tel No 020 8542 8082 - Email: [email protected] All correspondence to The Presbytery: 30 Park Road, Colliers Wood, London, SWl9 2HS - Tel No. 020 8540 3057 Parish Priest Fr Agnelo de Souza 020 8540 3057 Parish Secretary : 07970157922 E: [email protected] Safeguarding Contacts; Mobile number 07485189950 Helen McHugh email; [email protected] Vincent Bolt email; [email protected] St George’s Hospital Chaplaincy via the switchboard on 020 8672 1255 or contact the Catholic Chaplain, Direct Line 020 8725 3069. Email: [email protected] . Confessions: Sat 5.30-5.50pm. (or at reasonable request). Hall bookings: 020 8542 3288(suspended)Web address www.stjosephscollierswood.co.uk PENTECOST SUNDAYOF EASTER Saturday 22nd.May Mass 6.00pm Intentions of Rosanne &Michael Sunday 23rd. May Mass 9.00am Dini Siby 50th. Birthday Sunday 23rd. May Mass10.45am Kim and Sandra Kwong.Thank you God for good health. Monday 24th. May Devotion 9.00am Mass 9.30am Jakub Dankiewicz RIP Tuesday 25th. May Devotion 9.00am Mass 9.30am Jakub Dankiewicz Wednesday 26th. May Devotion 9.00am Tony Kimming Birthday Thursday 27th. May Devotion 9.00am Mass 9.30am Marjorie Fidge RIP Friday 28th. May Devotion 9.00am Mass 9.30am. Jakub Dankiewcz RIP Saturday 29th. May Mass 6.00pm Kevin McGowan RIP Sunday 30th. May Mass 9.00am Intentions of Janina Sunday 30th. May. Mass11.00am. Confirmation Mass (candidates and family members) Please note that due to confirmation taking place at 11am.