Pitcairn Kfz-Registrierungssystem Pitcairn Vehicle Registration System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Privy Council on Appeal from the Court of Appeal of Pitcairn Islands

IN THE PRIVY COUNCIL ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF PITCAIRN ISLANDS No. of 2004 BETWEEN STEVENS RAYMOND CHRISTIAN First Appellant LEN CALVIN DAVIS BROWN Second Appellant LEN CARLISLE BROWN Third Appellant DENNIS RAY CHRISTIAN Fourth Appellant CARLISLE TERRY YOUNG Fifth Appellant RANDALL KAY CHRISTIAN Sixth Appellant A N D THE QUEEN Respondent CASE FOR STEVENS RAYMOND CHRISTIAN AND LEN CARLISLE BROWN PETITIONERS' SOLICITORS: Alan Taylor & Co Solicitors - Privy Council Agents Mynott House, 14 Bowling Green Lane Clerkenwell, LONDON EC1R 0BD ATTENTION: Mr D J Moloney FACSIMILE NO: 020 7251 6222 TELEPHONE NO: 020 7251 3222 6 PART I - INTRODUCTION CHARGES The Appellants have been convicted in the Pitcairn Islands Supreme Court of the following: (a) Stevens Raymond Christian Charges (i) Rape contrary to s7 of the Judicature Ordinance 1961 and s1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (x4); (ii) Rape contrary to s14 of the Judicature Ordinance 1970 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956. Sentence 4 years imprisonment (b) Len Carlisle Brown Charges Rape contrary to s7 of the Judicature Ordinance 1961, the Judicature Ordinance 1970, and s1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (x2). Sentence 2 years imprisonment with leave to apply for home detention The sentences have been suspended and the Appellants remain on bail pending the determination of this appeal. HUMAN RIGHTS In relation to human rights issues, contrary to an earlier apparent concession by the Public Prosecutor that the Human Rights Act 1978 applied to the Pitcairn Islands, it would appear not to have been extended to them, at least in so far as the necessary protocols to the Convention have not been signed to enable Pitcairners to appear before the European Court: R (Quark Fisheries Ltd) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2005] 3 WLR 7 837 (Tab ). -

Explorers Voyage

JANUARY 2021 EXPLORERS VOYAGE TOUR HIGHLIGHTS A LEGENDARY SEA VOYAGE AND LANDED VISITS TO ALL FOUR ISLANDS STARGAZING IN MATA KI TE RANGI 'EYES TO THE SKY' INTERNATIONAL DARK SKY SANCTUARY UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE, HENDERSON ISLAND EXPLORING THE 3RD LARGEST MARINE RESERVE ON EARTH FIRSTHAND INSIGHT INTO LIVING HISTORY AND CULTURE JANUARY 2021 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE A rare journey to Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie & Oeno Pitcairn Islands Tourism and Far and Away Adventures are pleased to present a 2021 small group Explorers Voyage to Oeno, Pitcairn, Ducie, and Henderson Island. Lying in the central South Pacific, the islands of Henderson, Ducie and Oeno support remarkably pristine habitats and are rarely visited by non-residents of Pitcairn. Pitcairn Islands This will be the second ever voyage of its Group kind — visiting all four of the islands in the Pitcairn Islands Group! . The 18-night/19-day tour includes 11-days cruising around the remote Pitcairn Islands group, stargazing in Pitcairn's new International Dark Sky Sanctuary named Mata ki te Rangi meaning 'Eyes To the Sky', exploring the world’s third largest marine reserve, landings on UNESCO World Heritage site Henderson Island and seldom visited Oeno and Ducie Island, as well as a 4-day stay on Pitcairn Island, during Bounty Day 2021, home of the descendants of the HMAV Bounty mutineers since 1790. JANUARY 2021 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE About the Pitcairn Islands Group The Pitcairn Islands Group forms the UK’s only Overseas Territory in the vast Pacific Ocean. With a total population of 50 residents and located near the centre of the planet’s largest ocean, the isolation of the Pitcairn Islands is truly staggering. -

In the Pitcairn Islands Supreme Court T 1/2011 In

IN THE PITCAIRN ISLANDS SUPREME COURT T 1/2011 IN THE MATTER under the Constitution of Pitcairn and the Bill of Rights 1688 AND IN THE MATTER OF a challenge to the vires of parts of the Pitcairn Constitution being ultra vires the Bill of Rights 1688 AND IN THE MATTER OF a constitutional challenge and the refusal of the Magistrates Court to refer a constitutional challenge to the Supreme Court and the failure of the Supreme Court to consider an appeal from the Magistrates Court AND CP 1/2013 IN THE MATTER OF a judicial review of the Attorney General and Governor BETWEEN MICHAEL WARREN Applicant/Appellant AND THE QUEEN Respondent Hearing: 07 to 11 and 14 to 17 April 2014; 01 August 2014; 23 September 2014 Appearances: Kieran Raftery and Simon Mount for the Crown Tony Ellis and Simon Park (on 23 September 2014) for Applicant/Appellant Judgment: 28 November 2014 ______________________________________________________________________ JUDGMENT OF HAINES J ______________________________________________________________________ This judgment was delivered by me on 28 November 2014 at 10 am pursuant to the directions of Haines J Deputy Registrar Table of Contents Para Nr Introduction [1] Course of the hearing [11] The application for a stay on the grounds of abuse of process – the self- determination claim The submission [19] The right to self-determination – sources [22] Ius cogens [24] Internal self-determination – treaty obligations of the UK – the Charter of the United Nations [32] Internal self-determination – treaty obligations of the UK – -

The World Factbook Australia-Oceania :: Norfolk Island

The World Factbook Australia-Oceania :: Norfolk Island (territory of Australia) Introduction :: Norfolk Island Background: Two British attempts at establishing the island as a penal colony (1788-1814 and 1825-55) were ultimately abandoned. In 1856, the island was resettled by Pitcairn Islanders, descendants of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian companions. Geography :: Norfolk Island Location: Oceania, island in the South Pacific Ocean, east of Australia Geographic coordinates: 29 02 S, 167 57 E Map references: Oceania Area: total: 36 sq km country comparison to the world: 235 land: 36 sq km water: 0 sq km Area - comparative: about 0.2 times the size of Washington, DC Land boundaries: 0 km Coastline: 32 km Maritime claims: territorial sea: 12 nm exclusive fishing zone: 200 nm Climate: subtropical; mild, little seasonal temperature variation Terrain: volcanic formation with mostly rolling plains Elevation extremes: lowest point: Pacific Ocean 0 m highest point: Mount Bates 319 m Natural resources: fish Land use: arable land: 0% permanent crops: 0% other: 100% (2011) Irrigated land: NA Natural hazards: typhoons (especially May to July) Environment - current issues: NA Geography - note: most of the 32 km coastline consists of almost inaccessible cliffs, but the land slopes down to the sea in one small southern area on Sydney Bay, where the capital of Kingston is situated People and Society :: Norfolk Island Nationality: noun: Norfolk Islander(s) adjective: Norfolk Islander(s) Ethnic groups: Australian 79.5%, New Zealander 13.3%, Filipino -

The Bounty's Bible

v Word Up! | Lesson 3 | April 20, 2013 The Bounty ’s Bible Sabbath Afternoon | Today’s Reading 2 Timothy 3:16, 17 (New International Version ) “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work.” Hebrews 4:12 (Contemporary English Version ) “What God has said isn't only alive and active! It is sharper than any double edged sword. His word can cut through our spirits and souls and through our joints and marrow, until it discovers the desires and thoughts of our hearts.” Child Guidance , p. 506 “The truths of the Bible, received, will uplift the mind from its earthliness and debasement. If the Word of God were appreciated as it should be, both young and old would possess an inward rectitude, strength of principle that would enable them to resist temptation.” Thoughts from the Mount of Blessing , pp. 18, 19 "Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled." Matthew 5:6 . “Righteousness is holiness, likeness to God, and ‘God is love.’ 1 John 4:16. It is conformity to the law of God, for ‘all Thy commandments are righteousness’ (Psalm 119:172), and ‘love is the fulfilling of the law’ (Romans 13:10). Righteousness is love, and love is the light and the life of God. The righteousness of God is embodied in Christ. We receive righteousness by receiving Him. “Not by painful struggles or wearisome toil, not by gift or sacrifice, is righteousness obtained; but it is freely given to every soul who hungers and thirsts to receive it. -

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography By Gary Shearer, Curator, Pitcairn Islands Study Center "1848 Watercolours." Pitcairn Log 9 (June 1982): 10-11. Illus in b&w. "400 Visitors Join 50 Members." Australasian Record 88 (July 30,1983): 10. "Accident Off Pitcairn." Australasian Record 65 (June 5,1961): 3. Letter from Mrs. Don Davies. Adams, Alan. "The Adams Family: In The Wake of the Bounty." The UK Log Number 22 (July 2001): 16-18. Illus. Adams, Else Jemima (Obituary). Australasian Record 77 (October 22,1973): 14. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Gilbert Brightman (Obituary). Australasian Record 32 (October 22,1928): 7. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Hager (Obituary). Australasian Record 26 (April 17,1922): 5. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, M. and M. R. "News From Pitcairn." Australasian Record 19 (July 12,1915): 5-6. Adams, M. R. "A Long Isolation Broken." Australasian Record 21 (June 4,1917): 2. Photo of "The Messenger," built on Pitcairn Island. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (April 30,1956): 2. Illus. Story of Miriam and her husband who labored on Pitcairn beginning in December 1911 or a little later. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 7,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 14,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 21,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 28,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (June 4,1956): 2. Adams, Miriam. "Letter From Pitcairn Island." Review & Herald 91 (Harvest Ingathering Number,1914): 24-25. -

Pitcairn Islands Eco Voyage

BOOK NOW Exclusive offer limited to 10 travelers. EXPLORERS VOYGAGE O C T O B E R 2 0 1 9 TOUR HIGHLIGHTS A LEGENDARY SEA VOYAGE STARGAZING IN AN INTERNATIONAL DARK SKY SANCTUARY UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE, HENDERSON ISLAND 3RD LARGEST MARINE RESERVE ON EARTH FIRSTHAND INSIGHT INTO LIVING HISTORY AND CULTURE WWW.VISITPITCAIRN.PN OCTOBER 2019 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE We look forward to welcoming you to our islands... Pitcairn Islands Tourism is pleased to present our 2019 small group Explorers Voyage to Oeno, Pitcairn, Ducie, and Henderson Island. Lying in the central South Pacific, the islands of Henderson, Ducie and Oeno support remarkably pristine habitats and are rarely visited by non-residents of Pitcairn. Pitcairn Islands This will be the first ever multi-island voyage Group of its kind--visiting all four of the islands in the Pitcairn Islands Group! . The 18-night/19-day tour includes 11 days cruising around the remote Pitcairn Islands, the world’s 3rd largest marine reserve, visiting UNESCO World Heritage listed Henderson Island, seldom visited Oeno and Ducie Island, and a 4 day stay on Pitcairn Island, home of the descendants of the HMAV Bounty mutineers since 1790. OCTOBER 2019 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE About the Pitcairn Islands Group The Pitcairn Islands Group forms the UK’s only Overseas Territory in the vast Pacific Ocean. With a total population of 50 residents and located near the centre of the planet’s largest ocean, the isolation of the Pitcairn Islands is truly staggering. The island group lies around 2,200 km from Tahiti, 2,100 km from Easter Island, and over 5,000 km (approximately the distance from London to New York) away from both New Zealand and South America. -

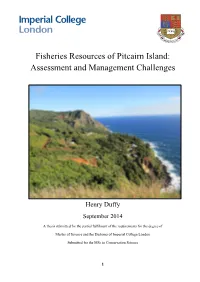

Fisheries Resources of Pitcairn Island: Assessment and Management Challenges

Fisheries Resources of Pitcairn Island: Assessment and Management Challenges Henry Duffy September 2014 A thesis submitted for the partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science and the Diploma of Imperial College London Submitted for the MSc in Conservation Science 1 Declaration of Own Work I declare that this thesis, “Fisheries Resources of Pitcairn Island: Assessment and Management Challenges”, is entirely my own work, and that where material could be construed as the work of others, it is fully cited and referenced, and/or with appropriate acknowledgement given. Signature Name of Student: Henry Duffy Names of Supervisors: Dr Heather Koldewey Dr Tom Letessier Robert Irving Professor Terry Dawson 2 Table of Contents List of Acronyms ................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Geography .................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 History ........................................................................................................................ -

The Youth's Instructor for 1953

INSTRUCTOR 14 --WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS MOOD It was March 2, and the District of Columbia was carpeted with snow, when the editor's schedule insisted on a spring- type editorial to be ready for the May 5 issue. After the first few bouts with seasonal reality, the vivid memories of Mr. Garrett's ranun- culuses helped span the miles and the months, and the writing was done. The plural of ranunculus, by the way, can be either ranun- culuses or ranunculi. ANSWER If you can give trusting assent to the prospects of a No answer to your prayer for life, you can claim a faith that is grown up and mature in every way. When such faith is found in the heart of a little girl, we think the story deserves a lead posi- tion in THE YOUTH'S INSTRUCTOR. We have given it just that. The story of Milly Jo, "When God Said Yes," was written by her Unseen Enemies maternal grandmother. Wherever springtime touches earth in this month of REPEAT Merlin L. Neff, author of the May, gentle showers abet a warm sun in the age-old wonder of Senior MV Book Club selection The Glory of the Stars (chapter excerpt beginning on bursting bud and springing flower. page 11), first appeared among Reading Out in Southern California a man takes pause to scan his Course authors in 1944 with the book Keepers fields. Acre on acre of brilliant blooms greet his eyes. Great of the Flame. Author Neff is the book editor patches of reds, whites, and blues make flag stripes across a field. -

The Legal History of Pitcairn Island, 1900-2010

LAW IN ISOLATION: THE LEGAL HISTORY OF PITCAIRN ISLAND, 1900-2010 Michael 0. Eshleman* I. THE WESTERN PACIFIC HIGH COMMISSION, 1898-1952..............22 II. CLAIMING ISLANDS: 1902 ............................... 23 III. IN WITH THE OLD: 1904.................................24 IV. NEILL'S DRAFT: 1937 ..................... ..... ......... 28 V. H.E. MAUDE: 1940-41 .................................. 30 VI. POST-WAR: 1952......................................36 VII. CONTINUED NEGLECT: 1950s ............................. 38 VIII. REENACTMENTS: 1960S....................... .......... 41 IX. You CAN'T GET THERE FROM HERE, 1960s To DATE.................43 X. FIJI INDEPENDENCE: 1970 ........................... 47 XI. RAPE INVESTIGATIONS: 1996.............................51 XII. THE GROWING STATUTE BOOK: 2000s............ .......... 55 XIII. RAPE PROSECUTIONS: 2003-06 .................... ...... 59 XIV. CONSTITUTION: 2010 ..................... ...... ........ 67 XV. THE NEXT STEPS ........................................ 69 XVI. A NOTE ON SOURCES .................................... 70 "Mis-ter Chris-tian!" is a bark echoing through the decades, a byword for insubordination, thanks to Charles Laughton's signature-and quite fanciful-performance as Captain William Bligh, R.N., commander of the Royal Navy's Bounty.' Her crew had just enjoyed seven months of leisure * Member of the Ohio Bar. J.D., University of Dayton School of Law; B.A. McMicken College of Arts & Sciences, University of Cincinnati. Former law clerk to Hon. Stephen A. Wolaver, Greene County Court of Common Pleas, Xenia, Ohio; formerly with Angstman Law Office, Bethel, Alaska. This article complements the Author's related A South Seas State of Nature: The Legal History ofPitcairnIsland, 1790- 1900, 29 UCLA PAC. BAsIN L.J. (forthcoming 2011), and The New Pitcairn Islands Constitution: Plenty of Strong Yet Empty Wordsfor Britain'sSmallest Colony, 24 PACE INT'L L. REv. (forthcoming 2012). 1. MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 1935); Charles Laughton, VARIETY, Dec. -

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography, Q to T

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography, Q to T By Gary Shearer, Curator, Pitcairn Islands Study Center Quintal, Flora (Obituary). Australasian Record 25 (May 16,1921): 10. On Norfolk Island. "Radio Station, Pitcairn Island." Australasian Record 43 (June 16,1939): 4. Picture of Andrew C. Young. Article from "Pacific Islands Monthly". "Radio Telephone for Pitcairn." Australasian Record 42 (March 28,1938): 3. Andrew Young, wireless operator. Raymond, Dale J. "Pitcairn Island Tracking Station, 1967." American Philatelist 107 (December 1993): 1126-1129. Illus. "Recent Actions of the Union Conference Committee." Australasian Record 28 (February 25,1924): 8. Voted that Pastor Robert Hare and wife be invited to work on Pitcairn. "Recent Impression of Pitcairn Islanders." Australasian Record 39 (January 28,1935): 3. "A Recent Letter From Pitcairn Island." Review & Herald 134 (November 21,1957): 32. A letter from Evelyn and Elwyn Christian to D.D. Fitch. "Recent Word From Pitcaairn." Review & Herald 132 (January 20,1955): 32. "Recently word came to us...." Australasian Record 37 (April 3,1933): 8. Pitcairners suffering a food shortage because of drought. Reilander, B. "The Ships of Pitcairn... A New Issue Backgrounder." Pitcairn Log 13 (March-May 1986): 5-7. "Relay of News from Norfolk and Pitcairn." Australasian Record 60 (October 1,1956): 5-6. "Report of the Island Mission Field of the Australasian Union Conference." Australasian Record 32 (October 15,1928): 1. Pitcairn article on page 1. Richards, H.M.S., Jr. "Pages of Power." Signs of the Times 101 (February 1974): 15-17. Illus. Includes a close-up photo of Bounty Bible. "Robert Pitcairn." Pitcairn Log 9 (June 1982): 8-9. -

Bounty Bible Made by the Island Council on the 30 November 2011 ______

GPI 028 Pitcairn Island Bounty Bible made by the Island Council on the 30 November 2011 ________ _________________________________________________________ ______ Background: Among all the books that arrived on Pitcairn onboard the Bounty in 1790 was the Bounty Bible . The Bounty Bible, donated by John Adams to a passing ship’s captain, was said to have been used by Mr Adams to teach the young ones, ended up in the archives of the Connecticut Historical Society. A century later a correspond ent with the late Roy Clark, managed to track down the Bounty Bible in 1945. A. W Moverley, school teacher to Pitcairn, wrote to the Society in 1948 and requested that the Bounty Bible be returned to Pitcairn. The Bible was consequently repaired and rebound in London then packed and sent first to Fiji where a wooden case was made for it with a glass top . I n February 1950 the Bible and the box was presented to the people of Pitcairn. The glass covered case, today, contains the Bible itself, a facsimile of William and Elizabeth Bligh’s marriage certificate, the standard flag used on the Pastor’s car during Prince Philip’s visit in 1971 and a New Testament in very small print donated to the church. In the drawer unde rneath the case are photos of the Bible before and after being rebound, some fragments of the old binding, and many letters written by the Hayden family relating to the Bounty Bible plus some newspaper clippings. The case containing all of the above was kept in the Seventh-Day Adventist Church but was moved to the museum in 2006.