1 an Introduction to Sociological Theories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

Conservation and the Myth of Consensus

Essays Conservation and the Myth of Consensus M. NILS PETERSON,∗ MARKUS J. PETERSON,† AND TARLA RAI PETERSON‡ ∗Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, 13 Natural Resources Building, East Lansing, MI 48824-1222, U.S.A., email [email protected] †Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258, U.S.A. ‡Department of Communication, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0491, U.S.A. Abstract: Environmental policy makers are embracing consensus-based approaches to environmental de- cision making in an attempt to enhance public participation in conservation and facilitate the potentially incompatible goals of environmental protection and economic growth. Although such approaches may pro- duce positive results in immediate spatial and temporal contexts and under some forms of governance, their overuse has potentially dangerous implications for conservation within many democratic societies. We suggest that environmental decision making rooted in consensus theory leads to the dilution of socially powerful con- servation metaphors and legitimizes current power relationships rooted in unsustainable social constructions of reality. We also suggest an argumentative model of environmental decision making rooted in ecology will facilitate progressive environmental policy by placing the environmental agenda on firmer epistemological ground and legitimizing challenges to current power hegemonies that dictate unsustainable practices. Key Words: democracy, environmental conflict, -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Ethnicity As a Construct in Leisure Research: a Rejoinder to Gobster

Joumat of Leisure Research Copyright 2007 2007, Voi 39, No. 3, pp. 554-566 National Recreation and Park Association Ethnicity as a Construct in Leisure Research: A Rejoinder to Gobster Garry Chick The Pennsylvania State University Chieh-lu Li The University of Hong Kong Harry C. Zinn The Pennsylvania State University James D. Absher The USDA Forest Service Alan R. Graefe The Pennsylvania State University Gobster addresses several issues in our paper. These include, first, a suggestion that the measure of cultural values that we used is not appropriate for understanding possible variations in racial and ethnic patterns of' outdoor leisure preferences and behavior. He claims, as well, that we limit our use of ethnicity to alleged cultural differences among groups and, specifically, to cultural values, unlike what most leisure researchers have done. Second, Gobster questions our concern with the use of common racial and ethnic labels because these are part and parcel of the way in which people look at others. Third, grouping people by racial and ethnic labels has often contrib- uted to social justice. Fourth, ethnic groups in the U.S. are growing and what may have been small differences between groups in the past may be mag- nified in the future due to these demographic shifts. Fifth, research is con- strained by resources that limit sampling designs and, therefore, collapsing smaller ethnic and/or racial groups into larger ones may be required for statistical comparisons of adequate power to be made. Sixth, Gobster ex- presses concern over our use of' cultural consensus analysis, a single method, in claiming that ethnicity may not be a useful concept. -

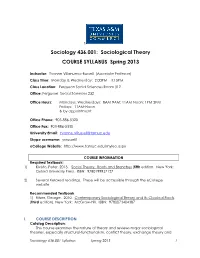

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise Max Coleman Oberlin College Sociology Department Senior Honors Thesis April 2014 Table of Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 I. What Is Anomie? Introduction 6 Anomie in The Division of Labor 9 Anomie in Suicide 13 Debate: The Causes of Desire 23 A Sidenote on Dualism and Neuroplasticity 27 Merton vs. Durkheim 29 Critiques of Anomie Theory 33 Functionalist? 34 Totalitarian? 38 Subjective? 44 Teleological? 50 Positivist? 54 Inconsistent? 59 Methodologically Unsound? 61 Sexist? 68 Overly Biological? 71 Identical to Egoism? 73 In Conclusion 78 The Decline of Anomie Theory 79 II. Why Anomie Still Matters The Anomic Nation 90 Anomie in American History 90 Anomie in Contemporary American Society 102 Mental Health 120 Anxiety 126 Conclusions 129 Soldier Suicide 131 School Shootings 135 III. Looking Forward: The Solution to Anomie 142 Sociology as a Guiding Force 142 Gemeinschaft Within Gesellschaft 145 The Religion of Humanity 151 Final Thoughts 155 Bibliography 158 2 To those who suffer in silence from the pain they cannot reveal. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Professor Vejlko Vujačić for his unwavering support, and for sharing with me his incomparable sociological imagination. If I succeed as a professor of sociology, it will be because of him. I am also deeply indebted to Émile Durkheim, who first exposed the anomic crisis, and without whom no one would be writing a sociology thesis. 3 Abstract: The term anomie has declined in the sociology literature. Apart from brief mentions, it has not featured in the American Sociological Review for sixteen years. Moreover, the term has narrowed and is now used almost exclusively to discuss deviance. -

Rights, Needs, and the Creation of Ethical Community Natalie Susan Gaines Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Rights, needs, and the creation of ethical community Natalie Susan Gaines Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Gaines, Natalie Susan, "Rights, needs, and the creation of ethical community" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2317. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2317 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RIGHTS, NEEDS, AND THE CREATION OF ETHICAL COMMUNITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Natalie Susan Gaines B.A., University of Louisville, 2005 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2011 ©Copyright 2011 Natalie Susan Gaines All rights reserved ii To my wonderful parents, Kenneth and Charlotte, without whose unfaltering love and encouragement this dissertation never would have been possible iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should probably begin by thanking the individual who set me on the road to academia, Dr. Gary L. Gregg, II at the University of Louisville. In my early years as an undergraduate, I was unsure of the path I would take after graduation. Dr. Gregg served as a wonderful mentor and opened my eyes to the vocation of teaching and the excitement of political theory. -

Contemporary Sociological Theory

Contemporary Sociological Theory An Integrated Multi-Level Approach Doyle Paul Johnson Contemporary Sociological Theory An Integrated Multi-Level Approach Doyle Paul Johnson Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX USA [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-387-76521-1 e-ISBN: 978-0-387-76522-8 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-76522-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008923257 © 2008 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 springer.com Preface This volume is designed as a basic text for upper level and graduate courses in contemporary sociological theory. Most sociology programs require their majors to take at least one course in sociological theory, sometimes two. A typical breakdown is between classical and contemporary theory. Theory is perhaps one of the broad- est areas of sociological inquiry and serves as a foundation or framework for more specialized study in specific substantive areas of the field. -

Book Reviews

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 76 | Issue 2 Article 6 1985 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Book Reviews, 76 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 512 (1985) This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/85/7602-512 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 76. No. 2 Copyright 0 1985 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in US.A. BOOK REVIEWS THE CONSENSUS-CONFLICT DEBATE. By Thomas J. Bernard. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983. Pp. 229. $28.00 (cloth), $14.00 (paper). Approximately fifteen years ago, a major debate raged in aca- demic sociology between theorists identified as consensus oriented and those defined as conflict oriented. A central theme of this great debate was whether social order was best described as emerging from a commonly held set of values and beliefs (the consensus posi- tion) or is, instead, due to power and coercion (the conflict posi- tion). Although much was written by both sides, the debate never attained satisfactory closure and the issue slowly faded from socio- logical attention. Now there appears in journals only scattered es- says related to the consensus-conflict debate. In his book, Thomas Bernard has not only resurrected the consensus-conflict debate, he has made it more general by examining the writings of classical moral and legal philosophers as well as sociologists.