TCRP Report 45: Passenger Information Services: a Guidebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammoth Summer Transit Map -2021

TOWN TROLLEY SERVICE Get across town with stops at Snowcreek Athletic Club, Minaret Village Shopping Center, The Village, Canyon Lodge and Juniper Springs Resort every 20 minutes. The open-air Lakes Basin Trolley leaves The Village for the Mammoth Lakes Basin every 30 minutes, MAMMOTH LAKES TRANSIT stopping at most of the lakes in the Mammoth Lakes Basin and providing access to area hiking trails. Also tows a 14-bike trailer for access to cycling. SUMMER SERVICE TROLLEY SERVICE ROUTE DATES TIMES FREQUENCY LOCATION TOWN Snowcreek Athletic Club May 28 – Jun 25 7 am – 10 pm Every 30 minutes See map inside COVID-19 REGULATIONS to The Village Jun 26 – Sep 6 7 am – 2 am Every 20 minutes (30 minutes after midnight) See map inside TROLLEY Masks are required. Please do not ride the bus if you are ill. to Canyon Lodge Sep 7 – Nov 19 7 am – 10 pm Every 30 minutes See map inside Schedules are subject to change without notice, please see TROLLEY SERVICE ROUTE DATES TIMES FREQUENCY LOCATION TIME LAST BUS estransit.com for current schedules. The Village to May 28 – Jun 25 9 am – 6 pm Weekends & holidays every 30 minutes, The Village / Stop #90 :00 and :30 5:00 LAKES BASIN WELCOME ABOARD! The Mammoth Transit summer system operates from TRANSIT MAP Lakes Basin weekdays every 60 minutes Lake Mary Marina / Stop #100 :19 and :49 5:19 TROLLEY Jun 26 – Aug 22 9 am – 6 pm Every 30 minutes Horseshoe Lake / Stop #104 :30 and :00 5:30 May 28 through November 19, 2021 and offers a convenient, fun and friendly (with 14-bike trailer) Aug 23 – Sep 6 9 am – 6 pm Weekends & holiday every 30 minutes, Tamarack Lodge (last bus)/Stop #95 :42 and :12 5:42 alternative to getting around Mammoth Lakes. -

Guidelines for the Safe Siting of School Bus Stops

Guidelines for the safe location of school bus stops 1. How are bus stops determined? Bus stops will be placed on public roadways and will avoid travel on private roads and/or driveways Bus routes are designed with buses traveling on main arterials with students picked up and dropped off at central locations. Visibility – Bus drivers need to have at least 500 feet of visible roadway to the bus stop. If there is not ample visibility (e.g. curve or hill) a “school bus stop ahead sign” is put in place before the stop in accordance with WAC 392-145-030 Bus drivers activate their school bus warning lights 300-100 feet before arriving at the bus stop, where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and under, and 500-300 feet before arriving at the bus stop where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and over. 2. Why are bus stops located at corners? Bus stops may be located at corners or intersections whenever possible. Corner stops are much more visible to drivers than house numbers. Students are generally taught to cross at corners rather than in the middle of the street. Traffic controls, such as stoplights or signs, are located at corners. These tend to slow down motorists at corners, making them more cautious as they approach intersections. The motoring public generally expects school buses to stop at corners rather than individual houses. Impatient motorists are also less likely to pass buses at corners than along a street. Cars passing school buses create the greatest risk to students who are getting on or off the bus. -

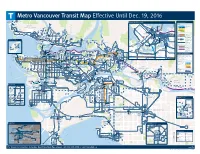

For Transit Information, Including Real-Time Next Bus, Please Call 604.953.3333 Or Visit Translink.Ca

Metro Vancouver Transit Map Effective Until Dec. 19, 2016 259 to Lions Bay Ferries to Vancouver Island, C12 to Brunswick Beach Bowen Island and Sunshine Coast Downtown Vancouver Transit Services £ m C Grouse Mountain Skyride minute walk SkyTrain Horseshoe Bay COAL HARBOUR C West End Coal Harbour C WEST Community Community High frequency rail service. Canada Line Centre Centre Waterfront END Early morning to late Vancouver Convention evening. £ Centre C Canada Expo Line Burrard Tourism Place Vancouver Millennium Line C Capilano Salmon Millennium Line Hatchery C Evergreen Extension Caulfeild ROBSON C SFU Harbour Evelyne Capilano Buses Vancouver Centre Suspension GASTOWN Saller City Centre BCIT Centre Bridge Vancouver £ Lynn Canyon Frequent bus service, with SFU Ecology Centre Art Gallery B-Line Woodward's limited stops. UBC Robson Sq £ VFS £ C Regular Bus Service Library Municipal St Paul's Vancouver Carnegie Service at least once an hour Law Edgemont Hall Community Centre CHINATOWN Lynn Hospital Courts during the daytime (or College Village Westview Valley Queen -

Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (Part B)

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 2 BUS TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. BUS CAPACITY BASICS ....................................................................................... 2-1 Overview..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 2-1 Types of Bus Facilities and Service ............................................................................ 2-3 Factors Influencing Bus Capacity ............................................................................... 2-5 Vehicle Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-5 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-13 Fundamental Capacity Calculations .......................................................................... 2-15 Vehicle Capacity................................................................................................... 2-15 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-22 Planning Applications ............................................................................................... 2-23 2. OPERATING ISSUES............................................................................................ 2-25 Introduction.............................................................................................................. -

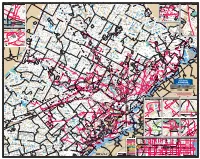

SEPTA Suburban St & Transit Map Web 2021

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA BB CC Stoneback Rd Old n d California Rd w d Rd Fretz Rd R o t n R d Dr Pipersville o Rd Smiths Corner i Rd Run Rd Steinsburg t n w TohickonRd Eagle ta Pk Rolling 309 a lo STOCKTON S l l Hill g R Rd Kellers o Tollgate Rd in h HAYCOCK Run Island Keiser p ic Rd H Cassel um c h Rd P Portzer i Tohickon Rd l k W West a r Hendrick Island Tavern R n Hills Run Point Pleasant Tohickon a Norristown Pottstown Doylestown L d P HellertownAv t 563 Slotter Bulls Island Brick o Valley D Elm Fornance St o i Allentown Brick TavernBethlehem c w Carversvill- w Rd Rd Mervine k Rd n Rd d Pottsgrove 55 Rd Rd St Pk i Myers Rd Sylvan Rd 32 Av n St Poplar St e 476 Delaware Rd 90 St St Erie Nockamixon Rd r g St. John's Av Cabin NJ 29 Rd Axe Deer Spruce Pond 9th Thatcher Pk QUAKERTOWN Handle R Rd H.S. Rd State Park s St. Aloysius Rd Rd l d Mill End l La Cemetery Swamp Rd 500 202 School Lumberville Pennsylvania e Bedminster 202 Kings Mill d Wismer River B V Orchard Rd Rd Creek u 1 Wood a W R S M c Cemetery 1 Broad l W Broad St Center Bedminster Park h Basin le Cassel Rockhill Rd Comfort e 1100 y Weiss E Upper Bucks Co. -

Directions from the Heathrow Terminals to the Airline Coach

Directions from the Heathrow Terminals to the Airline Coach Terminal 2 - Enter the arrivals area, here you will see lots of people waiting. - Exit the terminal building and walk to the elevators straight ahead - Take the elevator down to floor -1 - Turn right out of the elevator - Follow the signs to the Central Bus station - Take the travellator - You will see an elevator with signs on it to the Central Bus station and to the Chapel - Take the elevator up to floor 0 Central Bus station - Turn right out of the elevator and go to Exit A. - Go to Stand 15 and wait for the Airline coach Terminal 3 - Enter the arrivals area, here you will see lots of people waiting. - Straight ahead of you is a ramp. - Walk down the ramp following the signs to the Central Bus station - Take the travellator - Turn left to the Central Bus station - Turn left again following signs to the Central Bus station - Turn right - You will see an elevator with signs on it to the Central Bus station and to the Chapel - Take the elevator up to floor 0 Central Bus station - Turn right out of the elevator and go to Exit A. - Go to Stand 15 and wait for the Airline coach Terminal 4 - Enter the arrivals area, here you will see lots of people waiting. - Walk towards the sign that says ‘Meeting Point’ - Pass the shop called ‘Boots’ - Look for the sign which says ‘free transfer to all terminals’ - Pass the ticket machines and walk through the glass doorway. - Turn left towards the elevators and take the elevator down to floor -1 - Come out of the elevator and follow the signs -

Schedules & Route Maps

8/30/2021 Schedules & Route Maps NORTH KITSAP Save paper Scan the QR code to access this book online. COMPLETE GUIDE TO ROUTED BUS SCHEDULES 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 106, 301, 302, 307, 332, 333, 338, 344 & 390 Refer to the following individual schedules for additional service in this area: BI Ride • Kingston Ride • Kingston / Seattle Fast Ferry Do you have questions about a schedule? 360.377.BUSS (2877) 800.501.RIDE (7433) Email: [email protected] Connect with Us Kitsap Transit is Committed Visit Kitsap Transit online for the most up-to-date to Your Safety information and to subscribe to Rider Alerts. www.kitsaptransit.com Doing Our Part For assistance contact Customer Service In response to the pandemic, we’re doing everything 360.377.BUSS (2877) 800.501.RIDE (7433) we can to keep you healthy and safe when you ride. Email: [email protected] Face Coverings: Customers must wear Follow us @kitsaptransit a face covering to ride, unless exempt by law. Masks available upon request. Hablas español? Para obtener información sobre los servicios o tarifas de Kitsap Daily Disinfection: We disinfect Transit en español, llame al 1-800-501-7433 durante el horario regular de oficina. El personal de servicio al cliente le conectará a high-touch areas daily with a non-toxic un intérprete para ayudar a responder sus preguntas. cleaner certified to kill coronaviruses. Tagalog? Hand Sanitizer: Dispensers are Upang makakuha ng impormasyon tungkol sa mga serbisyo o singil ng Kitsap Transit sa wikang Tagalog, mangyaring installed on Routed and ACCESS buses. -

Transit Speed and Reliability Guidelines and Strategies

TRANSIT SPEED & RELIABILITY GUIDELINES & STRATEGIES AUGUST 2021 II KING COUNTY METRO SPEED AND RELIABILITY GUIDELINES AND STRATEGIES AUGUST 2021 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................1 5. CASE STUDIES ............................................................................ 99 2. OVERVIEW OF SPEED AND RELIABILITY ���������������������������������������3 5.1 RENTON, KENT, AUBURN AREA MOBILITY PROJECT ............... 100 2.1 WHAT ARE SPEED AND RELIABILITY? ........................................4 5.1.1 FORMING PARTNERSHIP .........................................................100 2.2 TYPES OF PROJECTS ..................................................................8 5.1.2 TOOLS IMPLEMENTED ............................................................101 2.3 BENEFITS OF SPEED AND RELIABILITY IMPROVEMENTS ...........12 5.1.3 LESSONS LEARNED ................................................................103 2.3.1 MEASURED BENEFITS .............................................................. 12 5.2 98TH AVENUE NE AND FORBES CREEK DRIVE QUEUE JUMP . 104 2.3.2 ACHIEVE REGIONAL AND LOCAL GOALS .................................. 14 5.2.1 FORMING PARTNERSHIP ........................................................104 2.3.3 SCALABLE SOLUTIONS ............................................................. 17 5.2.2 TOOLS IMPLEMENTED ............................................................106 2.3.4 BENEFITS TO OTHER MODES .................................................... 17 -

2017 Bus Stop Procedures Manual

2017 Bus Stop Procedures Manual GREENVILLE TRANSIT AUTHORITY dba GREENLINK Table of Contents Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Stop Parameters ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Bus Dimensions and turn radii .................................................................................................................. 3 Bus Stop Typology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Near-side ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Far-side .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Mid-block .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Stop Spacing and Placement ..................................................................................................................... 7 Service Delivery ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Stop Design/Environment ........................................................................................................................... -

BC Transit. "Design Guidelines for Accessible Bus Stops."

BC TRANSIT MUNICIPAL SYSTEMS PROGRAM DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR ACCESSIBLE BUS STOPS FORWARD -- MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS FOR DESIGNATION OF ACCESSIBLE BUS STOPS The guidelines for an accessible stop are: In areas where a sidewalk is the pedestrian right-of-way: The preferable roadside condition for a transit stop is a concrete barrier curb 150 mm (6 in) high, without indentation for a catch basin. The transit stop-waiting pad should be a clear minimum of 2.1 m (7 ft) x 1.98 m (6.5 ft). This is necessary in order to accommodate the wheelchair ramp deployment from the bus and to allow for wheelchair movement after clearing the ramp. Provide one or two paved connections from waiting pad to the sidewalk for a width of 1.5 m (5 ft). If street furniture or other such objects are provided (i.e. newspaper box, overhead signage), they must be located to provide a minimum clear width of 1.5 m (5 ft) and clear headroom of 2.0 m (6.5 ft) for the pedestrian path. They must be kept clear of the transit loading and unloading area. If a bench for seating is installed within bus stop areas, it should not be placed on a sidewalk after having a width of less than 2 m (6.5 ft), or within 6 m (20 ft) of any fire hydrant. In areas where no sidewalk exists, a concrete or asphalt pad on the shoulder of the road, as illustrated in Figure 6, is recommended. As illustrated, the pad must be elevated above road grade 150 mm. -

Explore: an Attraction Search Tool for Transit Trip Planning

Explore: An Attraction Search Tool for Transit Trip Planning Explore: An Attraction Search Tool for Transit Trip Planning Kari Edison Watkins, Brian Ferris, and G. Scott Rutherford University of Washington Abstract Publishing information about a transit agency’s stops, routes, schedules, and status in a variety of formats and delivery methods is an essential part of improving the usabil- ity of a transit system and the satisfaction of a system’s riders. A key staple of most transit traveler information systems is the trip planner, a tool that serves travelers well if the both origin and destination are known. However, sometimes the availabil- ity of transit at a location is more important than the actual destination. Given this premise, we developed an Attractions Search Tool to make use of an underlying trip planner to search online databases of local restaurants, shopping, parks and other amenities based on transit availability from the user’s origin. The ability to perform such a search by attraction type rather than specific destination can be a powerful aid to a traveler with a need or desire to use public transportation. Background Publishing information about a transit agency’s stops, routes, schedules, and status in a variety of formats and delivery methods is an essential part of improving the ease of use of a transit system and the satisfaction of a system’s riders. No longer the domain of just simple printed schedules, transit traveler information systems have grown to include route maps and timetables, trip planners, real-time track- ers, service alerts, and others tools made available across cell phones, web brows- ers, and new Internet devices as driven by rider demand (Multisystems 2003). -

Collaborative Research and Mapping for Public Transit Anywhere

Collaborative Research and Mapping for Public Transit Anywhere Application for IRU BUS Excellence Award July 2015 Vision/Goals Across the world, cities depend on buses as the critical core of their public transit system. In Africa, Asia, Latin America and elsewhere, transport authorities often do not exist and numerous operators run bus systems under the difficult conditions of high levels of informality. This means little to no information on routes, stops, fares and schedules (if they exist) is usually available. Yet this information is key to improving services, planning and providing basic passenger information important to smoother functioning of the system and higher customer satisfaction. This, in turn, is critical to a more sustainable, cleaner, low carbon future for these cities. Created to address this problem, Digital Matatus is a key player in the movement to leverage technological innovation, open data and collaborative networks to improve transportation in cities that depend on bus systems with high degrees of informality. We aim to make the bus services in these cities more visible, legible, service oriented, efficient, and open. Our work consists of engaging with operators, government, technology firms and civil society in a collaborative process to develop high quality open data on buses in standardized format that allows access to new tools. Through a collaborative process we support a community of users who can build on the data to generate innovation around transit applications, planning tools and passenger information systems. We support both the development of user-friendly technology for data collection Collaborative Research and Mapping for Public Transit Anywhere and local institutionalization of the knowledge and techniques of data collection to ensure long term, sustained data collection for bus improvements.