The Intersections of American Experimental Theatre and Absurd Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Siemund

Veranstalter: Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich Off-Off-Broadway and Beyond: Experimental Theatre Thema: and Avant-Garde Performance 1945–1970 [AA-A3, ENG-7, AA-W] Art der Veranstaltung: Seminar Ib Veranstaltungsnummer: 53-561 Zeit: Mo 18-20 Raum: Phil 1269 Beginn: 17. Oktober 2011 Course Description: The early developing OFF-OFF- BROADWAY MOVEMENT of the 1950s and 1960s sought freedom from the various constraints — aesthetically and otherwise — of conventional theatre. Mainstream theatre at the time was dominated by the musical and the psycho- logical drama, spawning pro- ductions that were conceived as business ventures and, if successful, packaged and toured. The notion of theatre as a packaged commodity offended the avant-garde sensibilities of artists who observed the psycho- logical and physical constraints built within the theatrical space itself. Instead, they enthusi- astically turned to alternative sites and experimental forms, eventually collapsing the dis- tinction between theatre and PERFORMANCE ART. While con- ventional theatre taught the spectator to lose herself in the fictional onstage time, space, and characters, avant-garde theatre and performance relied on the spectator’s complete consciousness of the present, i.e. the real time and space shared by audience and performers. The primary importance of the spectator’s consciousness of the present is that she is an active force in creating the theatrical event rather than a passive observer of a ready-made production. To approach this phenomenon, we will be looking closely at three significant avant-garde moments in postwar American theatre and performance: THE LIVING THEATRE, HAPPENINGS/FLUXUS, and the BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT. We will analyze and discuss experimental plays that still work within the confines of theatrical space, like The Connection (1959) and Dutchman (1964), semi-improvisational and interactive plays, like Paradise Now (1967), as well as Happenings and other ‘far-out’ performances. -

News Release for Immediate

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 30, 2020 OFF-BROADWAY CAST OF “THE WHITE CHIP”, SEAN DANIELS’ CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED PLAY ABOUT HIS UNUSUAL PATH TO SOBRIETY, WILL DO A LIVE ONLINE READING AS A BENEFIT Performance Will Benefit The Voices Project and Arizona Theatre Company and is dedicated to Terrence McNally. In line with Arizona Theatre Company’s (ATC) ongoing commitment to bringing diverse creative content to audiences online, the original Off-Broadway cast of The White Chip will perform a live reading of Artistic Director Sean Daniels’ play about his unusual path to sobriety as a fundraiser for The Voices Project, a grassroots recovery advocacy organization, and Arizona Theatre Company. The benefit performance will be broadcast live at 5 p.m. (Pacific Time) / 8 p.m. (Eastern Time), Monday, May 11 simultaneously on Arizona Theatre Company’s Facebook page (@ArizonaTheatreCompany) and YouTube channel. The performance is free, but viewers are welcome to donate what they can. The performance will then be available for four days afterwards through ATC’s website and YouTube channel. All donations will be divided equally between the two organizations. A New York Times Critics’ Pick, The White Chip was last staged Off-Broadway at 59E59 Theaters in New York City, from Oct. 4 - 26, 2019. Tony Award-nominated director Sheryl Kaller, Tony Award-winning sound designer Leon Rothenberg and the original Off- Broadway cast (Joe Tapper, Genesis Oliver, Finnerty Steeves) will return for the reading. The Off-Broadway production was co-produced with Tony Award-winning producers Tom Kirdahy (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown) and Hunter Arnold (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown). -

Through the Looking-Glass. the Wooster Group's the Emperor Jones

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 17 (2013) Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, pp.61-80 THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS. THE WOOSTER GROUP’S THE EMPEROR JONES (1993; 2006; 2009): REPRESENTATION AND TRANSGRESSION EMELINE JOUVE Toulouse II University; Champollion University. [email protected] Received April 26th, 2013 Accepted July 18th , 2013 KEYWORDS The Wooster Group; theatrical and social representation; boundaries of illusions; race and gender crossing; spectatorial empowerment. PALABRAS CLAVE The Wooster Group; representación teatral y social; fronteras de las ilusiones; cruzamiento racial y genérico; empoderamiento del espectador ABSTRACT In 1993, the iconoclastic American troupe, The Wooster Group, set out to explore the social issues inherent in O’Neill’s work and to shed light on their mechanisms by employing varying metatheatrical strategies. Starring Kate Valk as a blackfaced Brutus, The Wooster Group’s production transgresses all traditional artistic and social norms—including those of race and gender—in order to heighten the audience’s awareness of the artificiality both of the esthetic experience and of the actual social conventions it mimics. Transgression is closely linked to the notion of emancipation in The Wooster Group’s work. By crossing the boundaries of theatrical illusion, they display their eagerness to take over the playwright’s work in order to make it their own. This process of interpretative emancipation on the part of the troupe appears in its turn to be a source of empowerment for the members of the audience, who, because the distancing effects break the theatrical illusion, are invited to adopt an active writerly part in the creative process and thus to take on the responsibility of interpreting the work for themselves. -

Scenic Design for the Musical Godspell

Scenic design for the musical Godspell Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Sugarbaker Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2009 Master’s Examination Committee: Professor Dan Gray, M.F.A. Advisor Professor Mandy Fox, M.F.A. Professor Kristine Kearney, M.F.A. Copyright by Sarah Sugarbaker 2009 Abstract In April of 2009 the Ohio State University Theatre Department produced Godspell, a musical originally conceived by John‐Michael Tebelak with music by Stephen Schwartz. This production was built and technically rehearsed in the Thurber Theatre, and then moved to the Southern Theatre in downtown Columbus, OH. As the scenic designer of this production I developed an environment in which the actors and director created their presentation of the text. Briefly, the director’s concept (Appendix A) for this production was to find a way to make the production relevant to the local population. Godspell centers around the creation and support of a community, so by choosing to reference the City Center Mall, an empty shopping center in downtown Columbus, the need for making a change as a community was emphasized. This environment consisted of three large walls that resembled an obscured version of the Columbus skyline, inspired by advertisements within the shopping center. Each wall had enlarged newspapers that could be seen under a paint treatment of vibrant colors. The headlines on these papers referenced articles that the local paper has written about the situation at the shopping center, therefore making the connection more clear. -

Download Download

Teresa de Lauretis Futurism: A Postmodern View* The importance of Modernism and of the artistic movements of the first twenty or so years of this century need not be stressed. It is now widely acknowledged that the "historical avant-garde" was the crucible for most of the art forms and theories of art that made up the contemporary esthetic climate. This is evidenced, more than by the recently coined academic terms "neoavanguardia" and "postmodernism," 1 by objective trends in the culture of the last two decades: the demand for closer ties between artistic perfor- mance and real-life interaction, which presupposes a view of art as social communicative behavior; the antitraditionalist thrust toward interdisciplinary or even non-disciplinary academic curri- cula; the experimental character of all artistic production; the increased awareness of the material qualities of art and its depen- dence on physical and technological possibilities, on the one hand; on the other, its dependence on social conventions or semiotic codes that can be exposed, broken, rearranged, transformed. I think we can agree that the multi-directional thrust of the arts and their expansion to the social and the pragmatic domain, the attempts to break down distinctions between highbrow and popular art, the widening of the esthetic sphere to encompass an unprecedented range of phenomena, the sense of fast, continual movement in the culture, of rapid obsolescence and a potential transformability of forms are issues characteristic of our time. Many were already implicit, often explicit, in the project of the historical avant-garde. But whereas this connection has been established and pursued for Surrealism and Dada, for example, Italian Futurism has remained rather peripheral in the current reassessment; indeed one could say that it has been marginalized and effectively ignored. -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

BOOK &MUSIC by Joe Kinosian BOOK

BOOK & MUSIC by Joe Kinosian BOOK & LYRICS by Kellen Blair DIRECTED by Scott Schwartz Printer’s Ad Printer’s Ad LEARNING & EDUCATION USING THEATRE AS A CATALYST TO INSPIRE CREATIVITY “ATC’S EDUCATION DEPARTMENT HAS BEEN NOTHING SHORT OF A MIRACLE.” -Cheryl Falvo, Crossroads English Chair / Service Learning Coordinator Theatre skills help support critical thinking, decision-making, teamwork and improvisation. It can bridge the gap from imagination to reality. We inspire students to feel that anything is possible. LAST SEASON WE REACHED OVER 11,000 STUDENTS IN 80 SCHOOLS ACROSS 8 AZ COUNTIES For more information about our Learning & Education programs, visit EDUCATION.ARIZONATHEATRE.ORG IN THIS ISSUE November-December 2014 Title Page ............................................................................5 The Cast ............................................................................. 6 About the Play .......................................................................12 About Arizona Theatre Company .......................................................15 ATC Leadership .....................................................................20 The Creative Team ................................................................... 28 Staff forMurder for Two ..............................................................36 Board of Trustees ...................................................................40 Theatre Information ................................................................. 47 Corporate and Foundation Donors ....................................................49 -

The Sixth Act: an Event History

The Sixth Act: An Event History 2004-2005 Academic Workshop: The Sixth Act: A New Drama Initiative This workshop will officially launch The Sixth Act, MCC's new Drama Initiative, so in addition to mocking a rehearsal for Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, we also will talk about the initiative and its goals. Everyone interested in drama--for personal, political, artistic, and/or pedagogical reasons-- is invited! Academic Workshop: Mamet, Harassment, and the Stage The workshop will focus on interdisciplinary approaches to a dramatic text, using David Mamet’s provocative, challenging play Oleanna as a case study. Oleanna, which is widely taught and performed, tells the story of a college student who issues a formal sexual harassment complaint against her college professor. The play is difficult in part because it’s difficult to tell which character is the real victim—raising real questions about different forms of power. More than one version of a key scene will be shown and then a group of MCC colleagues from different academic perspectives will offer insight into the text based on their individual backgrounds. The idea is that a single dramatic text can yield multiple readings, and that we all are better equipped to approach a dramatic text when we have a wider understanding of some of these readings. Academic Workshop: "Unpack My Heart With Words": Using Dramatic Techniques to Understand Shakespeare's Language This interactive workshop will help students, teachers, and drama enthusiasts use performance to interpret the multiple dimensions of Shakespeare's words. Academic Workshop: Stagecraft 101: Understanding the Fundamentals of Design This hands-on workshop will familiarize participants with the language of scenic, sound, lighting, costume, and property design-providing important insight into practical as well as metaphoric applications of the stage. -

M E D I a R E L E A

PRESS CONTACT: PRESS CONTACT: Kate Kerns Leslie Crandell Dawes 503.445.3715 [email protected] [email protected] MEDIA RELEASE JOCELYN BIOH’S BREAKOUT HIT SCHOOL GIRLS; OR, THE AFRICAN MEAN GIRLS PLAY COMES TO PORTLAND IN HISTORIC CO-PRODUCTION “Ferociously entertaining and as heartwarming as it is hilarious.” – The Hollywood Reporter Previews Begin Jan. 18 | Opening Night is Jan. 24 | Closes Feb. 16 Dec. 26, 2020 — PORTLAND, OR. Jocelyn Bioh’s hit comedy School Girls; Or, The African Mean Girls Play, comes to Portland this January in a historic co-production between Artists Repertory Theatre and Portland Center Stage at The Armory. Inspired in part by Bioh’s mother’s time in a boarding school in Ghana, and Bioh’s own experience in at a boarding school in Pennsylvania, School Girls tells the story of Paulina, the reigning Queen Bee at Ghana’s most exclusive boarding school. Her dreams of winning the Miss Universe pageant are threatened by the arrival of Ericka, a new student with undeniable talent, beauty … and lighter skin. The New York Times called Bioh’s biting play about the challenges facing teenage girls across the globe “a gleeful African makeover of an American genre.” “Oftentimes, the stories about Africa that are being served up are usually tales of extreme poverty, struggle, strife, disease, and war,” said Bioh. “This narrative is a dangerous and calculated one, and it has always been my goal to present the Africa I know and love so dearly. School Girls was my first produced play, and I’m so thrilled at the reception.” Lava Alapai, who will direct School Girls, spoke to the importance of a comedic story centering Black teenage girls: “We seldom get to see Black women on stages that allow space for joy and community.” This production marks the first time that Artists Repertory Theatre and Portland Center Stage at The Armory have co-produced a show. -

Cultural Solidarity Coalition Opens Microgrant Applications for NYC Artists and Cultural Workers

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release February 16, 2021, New York City Contact: Hanna Stubblefield-Tave, [email protected] Cultural Solidarity Coalition Opens Microgrant Applications for NYC Artists and Cultural Workers Right now, 62% of arts and cultural workers are entirely unemployed, including more than 69% of Black and Indigenous artists and artists of color. Creative workers faced an average individual loss of $22,000 each in 2020. In response, NYC arts and cultural organizations created the new Cultural Solidarity Coalition to take care of their own communities. Now, the CULTURAL SOLIDARITY FUND will award $500 relief microgrants to individual artists and cultural workers to ensure that they make it through this critical time. Applications will open for one week from February 26, 2021, at 9:00 am, to March 5, 2021, at 5:00 pm. The short application is estimated to take no more than 10 minutes to complete and will be available online in both English and Spanish at culturalsolidarityfund.org/get-a-grant. The Cultural Solidarity Fund will initially open applications with $100,000 raised to support 200 artists and cultural workers. Organizations and individuals are invited to join the Coalition and increase the Fund’s capacity by sponsoring one or more artists/cultural workers with a donation: culturalsolidarityfund.org/sponsor. If additional funds are received, a new round of grants and/or lottery will be announced weekly. Cultural Solidarity Fund grants are open for artists and cultural workers who resided in the five boroughs of New York City as of April 1, 2020: Actors, Administrators, Choreographers, Custodians, Curators, Dancers, Designers, Directors, Drivers, Dramaturgs, Front of House, Guards, Janitors, Installers, Musicians, Playwrights, Production Managers, Receptionists, Technical Crew and Art Handlers, Stage Managers, Teaching Artists, Technicians, Ushers, Visual Artists, and anyone working in any capacity in the arts/cultural non-profit or community-based sector. -

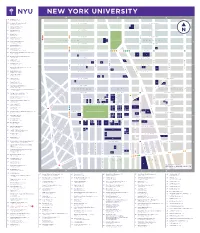

Nyu-Downloadable-Campus-Map.Pdf

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY 64 404 Fitness (B-2) 404 Lafayette Street 55 Academic Resource Center (B-2) W. 18TH STREET E. 18TH STREET 18 Washington Place 83 Admissions Office (C-3) 1 383 Lafayette Street 27 Africa House (B-2) W. 17TH STREET E. 17TH STREET 44 Washington Mews 18 Alumni Hall (C-2) 33 3rd Avenue PLACE IRVING W. 16TH STREET E. 16TH STREET 62 Alumni Relations (B-2) 2 M 25 West 4th Street 3 CHELSEA 2 UNION SQUARE GRAMERCY 59 Arthur L Carter Hall (B-2) 10 Washington Place W. 15TH STREET E. 15TH STREET 19 Barney Building (C-2) 34 Stuyvesant Street 3 75 Bobst Library (B-3) M 70 Washington Square South W. 14TH STREET E. 14TH STREET 62 Bonomi Family NYU Admissions Center (B-2) PATH 27 West 4th Street 5 6 4 50 Bookstore and Computer Store (B-2) 726 Broadway W. 13TH STREET E. 13TH STREET THIRD AVENUE FIRST AVENUE FIRST 16 Brittany Hall (B-2) SIXTH AVENUE FIFTH AVENUE UNIVERSITY PLACE AVENUE SECOND 55 East 10th Street 9 7 8 15 Bronfman Center (B-2) 7 East 10th Street W. 12TH STREET E. 12TH STREET BROADWAY Broome Street Residence (not on map) 10 FOURTH AVE 12 400 Broome Street 13 11 40 Brown Building (B-2) W. 11TH STREET E. 11TH STREET 29 Washington Place 32 Cantor Film Center (B-2) 36 East 8th Street 14 15 16 46 Card Center (B-2) W. 10TH STREET E. 10TH STREET 7 Washington Place 17 2 Carlyle Court (B-1) 18 25 Union Square West 19 10 Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (A-1) W. -

Itinera N. 3, 2012

Futurism and Experimentation in Italian Theater in the Late 20th Century di Alberto Bentoglio Abstract This paper aims to understand whether and to which extent the Futur- ism theory of theatre and its practices have influenced the Italian con- temporary scene. Common opinion still has it that Futurism has left lit- tle to no legacy in the Italian theatre, and we cannot properly speak of neo-futurism or of an active Futurist avant-garde. Nonetheless, taking a closer look at some of most significant figures in Italian experimental theatre (for example, Ivrea Manifesto’s project, Carmelo Bene, Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio) this paper aims to underline the many elements that trace back to Futurist’s theatre, suggesting the need to re-read futurist artistic experiences – at least in the field of performing arts – as con- structive practices aimed at the building of a new kind of theatre. In this paper I shall try to understand whether and to which extent the shades of Futurism in and on theatre have been present on the Italian scene. Common opinion still has it that Futurism has left little legacy in the practices of contemporary Italian theatre. Differently from the visual arts, architecture and literature, futurist influences have often been local. According to Silvio D’Amico’s and Renato Simoni’s old and, in my opinion, no more valid belief, they are limited exclusively to sce- nography: «Forse, nel campo del teatro, le influenze futuriste più appa- riscenti si sono avute in materia di scenografia […]. Da ricordare a questo proposito il nome del pittore Enrico Prampolini» (Probably, in the field of theatre, the most evident futurist influences concern sceno- graphy […].