Through the Looking-Glass. the Wooster Group's the Emperor Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember)

THE WOOSTER GROUP NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember) DIRECTOR’S NOTE Our work on this piece began when filmmaker Ken Kobland and I set out to make an archival video reconstruction of The Wooster Group’s 1978 piece Nayatt School. Nayatt School featured Spalding Gray’s first experiments with the monologue form and included scenes from T.S. Eliot’s play The Cocktail Party. Nayatt School was the third part of a trilogy of pieces that I directed that were made around Spalding’s autobiography: his family history, his life in the theater, and his mother’s suicide. As Ken and I worked with the Nayatt School materials, we found that the surviving video and audio recordings were too fragmentary, and their original quality too poor, to make a full reconstruction. So I decided to remount Nayatt School with our present company – especially while a few of us, who were there, could still remember. We could at least fill in the gaps for an archival record and, at the same time, demonstrate our process for devising our work. Of course, in reanimating Nayatt School, we have discovered that when it is placed in a new time and context, new possibilities and resonances emerge. I recognize that we are not just making an archival record — we are in the process of making a new piece. That is the work in progress that you are about to see. work-in-progress theatro-film THE PERFORMING GARAGE May 2019 NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember) with Ari Fliakos, Gareth Hobbs, Erin Mullin, Suzzy Roche, Scott Shepherd, Kate Valk, Omar Zubair Composed by the -

6. Emperor Jones As Expressionist Drama

EMPEROR JONES AS AN EXPRESSONIST DRAMA Vijayalakshmi Srinivas The Emperor Jones (written in 1920 and a great theatrical success) is about an American Negro, a Pullman porter who escapes to an island in the West Indies 'not self-determined by White Marines'. In two years, Jones makes himself 'Emperor' of the place. Luck has played a part and he has been quick to take advantage of it. A native tried to shoot Jones at point-blank range once, but the gun missed fire; thereupon Jones announced that he was protected by a charm and that only silver bullets could harm him. When the play begins, he has been Emperor long enough to amass a fortune by imposing heavy taxes on the islanders and carrying on all sorts of large-scale graft. Rebellion is brewing. The islanders are whipping up their courage to the fighting point by calling on the local gods and demons of the forest. From the deep of the jungle, the steady beat of a big drum sounded by them is heard, increasing its tempo towards the end of the play and showing the rebels' presence dreaded by the Emperor. It is the equivalent of the heart-beat which assumes a higher and higher pitch; while coming closer it denotes the premonition of approaching punishment and the climactic recoil of internal guilt of the black hero; he wanders and falters in the jungle, present throughout the play with its primeval terror and blackness. The play consists of a total of eight scenes arranged in hierarchical succession. The first and the last scenes are realistic in the manner of O'Neill's early plays. -

Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain a Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): Pionera Del Teatro Experimental

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 14 | 2017 Early American Surrealisms, 1920-1940 / Parable Art Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain A Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): pionera del teatro experimental. Trifles, los Provincetown Players y el teatro de vanguardia” (“Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): The Pioneer of Experimental Theatre. Trifles, the Provincetown Players and the Avant-garde Theatre”) Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10102 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.10102 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori, “Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain”, Miranda [Online], 14 | 2017, Online since 18 April 2017, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/10102 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.10102 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain 1 Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain A Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): pionera del teatro experimental. Trifles, los Provincetown Players y el teatro de vanguardia” (“Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): The Pioneer of Experimental Theatre. Trifles, the Provincetown Players and the Avant-garde Theatre”) Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori The International Susan Glaspell Society: Website 1 http://blogs.shu.edu/glaspellsociety/ Miranda, 14 | 2017 Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain 2 [Figure 1] Poster design by Noelia Hernando Real; photography by Nicholas Murray. Susan Glaspell, Trifles and the Hossack Case 2 Susan Glaspell was born in 1876 in Davenport, Iowa. -

The Emperor Jones

1 l1111•n" \J 11,•ill•ru1.Jeni• o'nrUJ•t>ugenr O•neUl•eugP.ne o'nrUl•r.ugene o'neUl•eugene o'nelll*eugene o'nolll*eugene •014,•� •l'nnlll•c>uqen,• o'm�Ul•Pugen<1 o'nelll•eugene o'nC!Ul•eugene o'neiU•eugene o'ne11l•eugena o'nellt•eugene •rugC'nC! o'neLU•eugC!ne o'neill•eugene o'nelll•eugene o'nelll•eugene o'nelll•e·u9ene •eugt"ne o'neUJ•eugene o'nelU•eugene o'neUl•eugene o'nelll*C!ugene o'nelll•eugene 1•iM1qon(' o'nelll*eugene o'n@tll• rine o'ne\U•eugene o•.,9 nlfl o'nell)•C!ugenia ·, �111•0'\l<Qo •n f'\O o· •111•,tllQ(tr) t•m19 servant - MARGIE M. DEAN DWYER harry smithers - LAURENCE O' ABOUT THE AUTOOR brutus jones - WILLIAM McGHEE haints or phantoms Often called America's foremost dramatist, Eugene O'Neill was the winner of three Pulitzer Prizes and the Nobel jeff - THEODORE (TED) MITCHELL P�ize for literature. Son of a famous actor, prison guard and auctioneer Eugene left - SOL JACKSON formal studies for the life of a coDDDOn seaman. After - TITUS ANDREWS five desperate and health-wrecking convicts, years of sailoring he slave - JIMMY L. ALLEN entered a TB sanatorium to regain his health. At enforced - MICHAEL TOLDEN 1:f!St, he turned to the literature of the stage for read - MISS DEAN ing. His brilliant t.n:iting career began upon his discharge - MR. TOLDEN witch doctor £rom the sanatorium. Although never in vigorous health , O'Neill wrote extensively. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Eugene O'neill's Strange Interlude

This dissertation has been 61-4507 microfilmed exactly as received WINCHESTER, Otis William, 1933- A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1961 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE ŒADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY OTIS WILLIAM WINCHESTER Tulsa, Oklahoma 1961 A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE APPROVEDB^ DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PREFACE Rhetoric, a philosophy of discourse and a body of theory for the management of special types of discourse, has been variously defined. Basic to any valid definition is the concept of persuasion. The descrip tion of persuasive techniques and evaluation of their effectiveness is the province of rhetorical criticism. Drama is, in part at least, a rhe torical enterprise. Chapter I of this study establishes a theoretical basis for the rhetorical analysis of drama. The central chapters con sider Eugene O'Neill's Strange Interlude in light of the rhetorical im plications of intent, content, and form. Chapter II deals principally with O'Neill's status as a rhetor. It asks, what are the evidences of a rhetorical purpose in his life and plays? Why is Strange Interlude an especially significant example of O'Neill's rhetoric? The intellectual content of Strange Interlude is the matter of Chapter III. What ideas does the play contain? To what extent is the play a transcript of con temporary thought? Could it have potentially influenced the times? Chapter IV is concerned with the specific manner in which Strange Interlude was used as a vehicle for the ideas. -

The Emperor Jones

The Emperor Jones Eugene O'Neill The Emperor Jones Table of Contents The Emperor Jones...................................................................................................................................................1 Eugene O'Neill...............................................................................................................................................1 SCENE ONE..................................................................................................................................................2 SCENE TWO...............................................................................................................................................10 SCENE THREE...........................................................................................................................................12 SCENE FOUR.............................................................................................................................................12 SCENE FIVE...............................................................................................................................................14 SCENE SIX..................................................................................................................................................15 SCENE SEVEN...........................................................................................................................................16 SCENE EIGHT............................................................................................................................................17 -

“A Luncheon for Suffrage

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 16 (2012) Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, 75-90 A LUNCHEON FOR SUFFRAGE: THEATRICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF HETERODOXY TO THE ENFRANCHISEMENT OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN NOELIA HERNANDO REAL Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Received 27th September 2012 Accepted 14th January 2013 KEYWORDS: Heterodoxy; US woman suffrage; theater; Susan Glaspell; Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Marie Jenney Howe; Paula Jakobi; George Middleton; Mary Shaw. PALABRAS CLAVE: Heterodoxy; sufragio femenino en EEUU; teatro; Susan Glaspell; Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Marie Jenney Howe; Paula Jakobi; George Middleton; Mary Shaw. ABSTRACT: This article explores and discusses the intertextualities that are found in selected plays written in the circle of Heterodoxy in the 1910s, the Greenwich Village-based radical club for unorthodox women. The article examines some of the parallels that can be found in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Something to Vote For, George Middleton’s Back of the Ballot, Mary Jenney Howe’s An Anti-Suffrage Monologue and Telling the Truth at the White House, written in collaboration with Paula Jakobi, Mary Shaw’s The Parrot Cage and The Woman of It, and Susan Glaspell’s Trifles, Bernice, Chains of Dew and Woman’s Honor. The works are put in the context of the national movement for woman suffrage and focuses on the authors’ arguments for suffrage as well as on their formal choices, ranging from realism to expressionism, satire and parody. RESUMEN: El presente artículo explora y discute las intertextualidades que se encuentran en una selección de obras escritas en el círculo de Heterodoxy, el club para mujeres no-ortodoxas con base en Greenwich Village, en la década de 1910. -

Kate Valk and Her Work with the Wooster Group

KATE VALK AND HER WORK WITH THE WOOSTER GROUP, YESTERDAY AND TODAY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University‐San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of ARTS by Melissa E. Jackson, B.A. San Marcos, Texas May 2009 KATE VALK AND HER WORK WITH THE WOOSTER GROUP, YESTERDAY AND TODAY Committee Members Approved: ______________________________ Debra Charlton, Chair ______________________________ Sandra Mayo ______________________________ Richard Sodders Approved: ____________________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Melissa E. Jackson 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Debra Charlton, Dr. Sandra Mayo, Dr. Richard Sodders, Dr. John Fleming, Texas State University-San Marcos, the Department of Theatre and Dance, and all my family and friends for their contributions to the writing of this thesis. This thesis was submitted on March 27, 2009. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................1 2. THE SERVANT ...........................................................................................18 3. THE NARRATOR........................................................................................31 4. THE PHYSICAL PERFORMER...................................................................48 5. CONCLUSION.............................................................................................60 -

Downloaded by Michael Mitnick and Grace, Or the Art of Climbing by Lauren Feldman

The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century by Gregory Stuart Thorson B.A., University of Oregon, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre This thesis entitled: The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century written by Gregory Stuart Thorson has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Dance _____________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland ____________________________________ Dr. James Symons Date ____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 12-0485 iii Abstract Thorson, Gregory Stuart (Ph.D. Department of Theatre) The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland New play development is an important component of contemporary American theatre. In this dissertation, I examined current models of new play development in the United States. Looking at Lincoln Center Theater and Signature Theatre, I considered major non-profit theatres that seek to create life-long connections to legendary playwrights. I studied new play development at a major regional theatre, Denver Center Theatre Company, and showed how the use of commissions contribute to its new play development program, the Colorado New Play Summit. I also examined a new model of play development that has arisen in recent years—the use of small black box theatres housed in large non-profit theatre institutions. -

Spring 2015 Issue of the Foundation’S Newsletter

April 2015 SOCIETY BOARD PRESIDENT Jeff Kennedy [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT J. Chris Westgate [email protected] SECRETARY/TREASURER Beth Wynstra [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY – ASIA: Haiping Liu [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY – Provincetown Players Centennial, 4-5 The Iceman Cometh at BAM, 6-7 EUROPE: Marc Maufort [email protected] GOVERNING BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIR: Steven Bloom [email protected] Jackson Bryer [email protected] Michael Burlingame [email protected] Robert M. Dowling [email protected] Thierry Dubost [email protected] Eugene O’Neill puppet at presentation of Monte Cristo Award to Nathan Lane, 8-9 Eileen Herrmann [email protected] Katie Johnson [email protected] What’s Inside Daniel Larner President’s message…………………..2-3 ‘Exorcism’ Reframed ……………….12-13 [email protected] Provincetown Players Centennial…….4-5 Member News………………….…...14-17 Cynthia McCown The Iceman Cometh/BAM……….……..6-7 Honorary Board of Directors..……...…17 [email protected] The O’Neill, Monte Cristo Award…...8-9 Members lists: New, upgraded………...17 Anne G. Morgan Comparative Drama Conference….10-11 Eugene O’Neill Foundation, Tao House: [email protected] Calls for Papers…………………….….11 Artists in Residence, Upcoming…...18-19 David Palmer Eugene O’Neill Review…………….….12 Contributors…………………………...20 [email protected] Robert Richter [email protected] EX OFFICIO IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT The Eugene O’Neill Society Kurt Eisen [email protected] Founded 1979 • eugeneoneillsociety.org THE EUGENE O’NEILL REVIEW A nonprofit scholarly and professional organization devoted to the promotion and Editor: William Davies King [email protected] study of the life and works of Eugene O’Neill and the drama and theatre for which NEWSLETTER his work was in large part the instigator and model. -

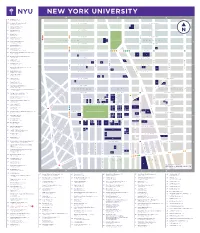

Nyu-Downloadable-Campus-Map.Pdf

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY 64 404 Fitness (B-2) 404 Lafayette Street 55 Academic Resource Center (B-2) W. 18TH STREET E. 18TH STREET 18 Washington Place 83 Admissions Office (C-3) 1 383 Lafayette Street 27 Africa House (B-2) W. 17TH STREET E. 17TH STREET 44 Washington Mews 18 Alumni Hall (C-2) 33 3rd Avenue PLACE IRVING W. 16TH STREET E. 16TH STREET 62 Alumni Relations (B-2) 2 M 25 West 4th Street 3 CHELSEA 2 UNION SQUARE GRAMERCY 59 Arthur L Carter Hall (B-2) 10 Washington Place W. 15TH STREET E. 15TH STREET 19 Barney Building (C-2) 34 Stuyvesant Street 3 75 Bobst Library (B-3) M 70 Washington Square South W. 14TH STREET E. 14TH STREET 62 Bonomi Family NYU Admissions Center (B-2) PATH 27 West 4th Street 5 6 4 50 Bookstore and Computer Store (B-2) 726 Broadway W. 13TH STREET E. 13TH STREET THIRD AVENUE FIRST AVENUE FIRST 16 Brittany Hall (B-2) SIXTH AVENUE FIFTH AVENUE UNIVERSITY PLACE AVENUE SECOND 55 East 10th Street 9 7 8 15 Bronfman Center (B-2) 7 East 10th Street W. 12TH STREET E. 12TH STREET BROADWAY Broome Street Residence (not on map) 10 FOURTH AVE 12 400 Broome Street 13 11 40 Brown Building (B-2) W. 11TH STREET E. 11TH STREET 29 Washington Place 32 Cantor Film Center (B-2) 36 East 8th Street 14 15 16 46 Card Center (B-2) W. 10TH STREET E. 10TH STREET 7 Washington Place 17 2 Carlyle Court (B-1) 18 25 Union Square West 19 10 Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (A-1) W. -

The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity Brenda Murphy Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521838525 - The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity Brenda Murphy Frontmatter More information The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity The Provincetown Players was a major cultural institution in Greenwich Village from 1916 to 1922, when American Modernism was being conceived and developed. This study considers the group’s vital role and its wider significance in twentieth- century American culture. Describing the varied and often contentious response to modernity among the Players, Murphy reveals the central contribution of the group of poets around Alfred Kreymborg’s Others magazine, including William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Mina Loy, and Djuna Barnes, and such modernist artists as Marguerite and William Zorach, Charles Demuth, and Bro¨r Nordfeldt, to the Players’ developing modernist aesthetics. The impact of their modernist art and ideas on such central Provincetown figures as Eugene O’Neill, Susan Glaspell, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, and a second generation of artists, such as e. e. cummings and Edmund Wilson, who wrote plays for the Provincetown Playhouse, is evident in Murphy’s close analysis of over thirty plays. BRENDA MURPHY is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Connecticut. She is the author of O’Neill: Long Day’s Journey into Night (2001), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film and Television (1999), Miller: Death of a Salesman (1995), Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), and American Realism and American Drama, 1880–1940 (1987), all published by Cambridge University Press. She has edited Understanding Death of a Salesman (with Susan Abbotson, 1999), The Cambridge Companion to American Women Playwrights (1999), and A Realist in the American Theatre: Selected Drama Criticism of William Dean Howells (1992).