“A Luncheon for Suffrage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Through the Looking-Glass. the Wooster Group's the Emperor Jones

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 17 (2013) Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, pp.61-80 THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS. THE WOOSTER GROUP’S THE EMPEROR JONES (1993; 2006; 2009): REPRESENTATION AND TRANSGRESSION EMELINE JOUVE Toulouse II University; Champollion University. [email protected] Received April 26th, 2013 Accepted July 18th , 2013 KEYWORDS The Wooster Group; theatrical and social representation; boundaries of illusions; race and gender crossing; spectatorial empowerment. PALABRAS CLAVE The Wooster Group; representación teatral y social; fronteras de las ilusiones; cruzamiento racial y genérico; empoderamiento del espectador ABSTRACT In 1993, the iconoclastic American troupe, The Wooster Group, set out to explore the social issues inherent in O’Neill’s work and to shed light on their mechanisms by employing varying metatheatrical strategies. Starring Kate Valk as a blackfaced Brutus, The Wooster Group’s production transgresses all traditional artistic and social norms—including those of race and gender—in order to heighten the audience’s awareness of the artificiality both of the esthetic experience and of the actual social conventions it mimics. Transgression is closely linked to the notion of emancipation in The Wooster Group’s work. By crossing the boundaries of theatrical illusion, they display their eagerness to take over the playwright’s work in order to make it their own. This process of interpretative emancipation on the part of the troupe appears in its turn to be a source of empowerment for the members of the audience, who, because the distancing effects break the theatrical illusion, are invited to adopt an active writerly part in the creative process and thus to take on the responsibility of interpreting the work for themselves. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain a Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): Pionera Del Teatro Experimental

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 14 | 2017 Early American Surrealisms, 1920-1940 / Parable Art Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain A Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): pionera del teatro experimental. Trifles, los Provincetown Players y el teatro de vanguardia” (“Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): The Pioneer of Experimental Theatre. Trifles, the Provincetown Players and the Avant-garde Theatre”) Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10102 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.10102 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori, “Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain”, Miranda [Online], 14 | 2017, Online since 18 April 2017, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/10102 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.10102 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain 1 Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain A Review of the Exhibition “Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): pionera del teatro experimental. Trifles, los Provincetown Players y el teatro de vanguardia” (“Susan Glaspell (1876-1948): The Pioneer of Experimental Theatre. Trifles, the Provincetown Players and the Avant-garde Theatre”) Quetzalina Lavalle Salvatori The International Susan Glaspell Society: Website 1 http://blogs.shu.edu/glaspellsociety/ Miranda, 14 | 2017 Celebrating Susan Glaspell and Trifles in Spain 2 [Figure 1] Poster design by Noelia Hernando Real; photography by Nicholas Murray. Susan Glaspell, Trifles and the Hossack Case 2 Susan Glaspell was born in 1876 in Davenport, Iowa. -

Iron Jawed Angels

Voting Rights Under Attack: An NCJW Toolkit to Protect the Vote Film Screening and Discussion: Iron Jawed Angels Films can offer a good basis for discussion and further understanding of important subjects. A film program that includes a screening, facilitated discussion, and perhaps even a speaker, can be an excellent way for NCJW members and supporters to learn more about and get involved in an issue. Iron Jawed Angels, film by Katja von Garnier: In the early twentieth century, the American women’s suffrage movement mobilized and fought to grant women the right to vote. Watch Alice Paul (Hilary Swank) and Lucy Burns (Frances O’Connor) as they fight for women’s suffrage and revolutionize the American feminist movement. Preparation for the Film Screening: Ñ Remind participants to be prepared to discuss how the film relates to NCJW’s mission. Ñ Encourage participants to bring statistics and information about voter rights in your community. Ñ Confirm location and decide who is bringing snacks and beverages. Ñ Ensure a facilitator is prepared to ask questions and guide discussion. Ñ Download and print copies of NCJW’s Promote the Vote. Protect the Vote Resource Guide. Discussion Questions to Consider: Ñ Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Women’s Party conducted marches, picketed the White House, and held rallies. What ways can you mobilize and influence your local, state, and federal elected officials? Ñ Lucy Burns discusses the “dos and don’ts” of lobbying, which include knowing the background of the member, being a good listener, and not losing your temper. Do you think these www.ncjw.org June 2016 4 Voting Rights Under Attack: An NCJW Toolkit to Protect the Vote rules have changed in the past 100 years? If so, how? What other “dos and don’ts” can you think of? Ñ How did the film portray racism within the women’s suffrage movement? How did racism linger in the feminist movement? Ñ In the film, the methods of the National Women’s Party and the National American Women’s Suffrage Association are contrasted. -

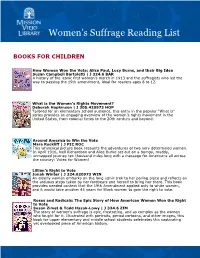

Women's Suffrage Reading List

Women’s Suffrage Reading List BOOKS FOR CHILDREN How Women Won the Vote: Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and their Big Idea Susan Campbell Bartoletti | J 324.6 BAR A history of the iconic first women's march in 1913 and the suffragists who led the way to passing the 19th amendment, ideal for readers ages 8 to 12. What is the Women’s Rights Movement? Deborah Hopkinson | J 305.420973 HOP Tailored for an elementary school audience, this entry in the popular “What is” series provides an engaging overview of the women’s rights movement in the United States, from colonial times to the 20th century and beyond. Around America to Win the Vote Mara Rockliff | J PIC ROC This whimsical picture book recounts the adventures of two very determined women. In April 1916, Nell Richardson and Alice Burke set out on a bumpy, muddy, unmapped journey ten thousand miles long with a message for Americans all across the country: Votes for Women! Lillian’s Right to Vote Jonah Winter | J 324.620973 WIN An elderly woman embarks on the long uphill trek to her polling place and reflects on the arduous steps taken by her forebears and herself to bring her there. This book provides needed context that the 19th Amendment applied only to white women, and it would take another 45 years for Black women to gain the right to vote. Roses and Radicals: The Epic Story of How American Women Won the Right to Vote Susan Zimet & Todd Hasak-Lowy | J 324.6 ZIM The story of women's suffrage is epic, frustrating, and as complex as the women who fought for it. -

Downloaded by Michael Mitnick and Grace, Or the Art of Climbing by Lauren Feldman

The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century by Gregory Stuart Thorson B.A., University of Oregon, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre This thesis entitled: The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century written by Gregory Stuart Thorson has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Dance _____________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland ____________________________________ Dr. James Symons Date ____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 12-0485 iii Abstract Thorson, Gregory Stuart (Ph.D. Department of Theatre) The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland New play development is an important component of contemporary American theatre. In this dissertation, I examined current models of new play development in the United States. Looking at Lincoln Center Theater and Signature Theatre, I considered major non-profit theatres that seek to create life-long connections to legendary playwrights. I studied new play development at a major regional theatre, Denver Center Theatre Company, and showed how the use of commissions contribute to its new play development program, the Colorado New Play Summit. I also examined a new model of play development that has arisen in recent years—the use of small black box theatres housed in large non-profit theatre institutions. -

Spring 2015 Issue of the Foundation’S Newsletter

April 2015 SOCIETY BOARD PRESIDENT Jeff Kennedy [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT J. Chris Westgate [email protected] SECRETARY/TREASURER Beth Wynstra [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY – ASIA: Haiping Liu [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY – Provincetown Players Centennial, 4-5 The Iceman Cometh at BAM, 6-7 EUROPE: Marc Maufort [email protected] GOVERNING BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIR: Steven Bloom [email protected] Jackson Bryer [email protected] Michael Burlingame [email protected] Robert M. Dowling [email protected] Thierry Dubost [email protected] Eugene O’Neill puppet at presentation of Monte Cristo Award to Nathan Lane, 8-9 Eileen Herrmann [email protected] Katie Johnson [email protected] What’s Inside Daniel Larner President’s message…………………..2-3 ‘Exorcism’ Reframed ……………….12-13 [email protected] Provincetown Players Centennial…….4-5 Member News………………….…...14-17 Cynthia McCown The Iceman Cometh/BAM……….……..6-7 Honorary Board of Directors..……...…17 [email protected] The O’Neill, Monte Cristo Award…...8-9 Members lists: New, upgraded………...17 Anne G. Morgan Comparative Drama Conference….10-11 Eugene O’Neill Foundation, Tao House: [email protected] Calls for Papers…………………….….11 Artists in Residence, Upcoming…...18-19 David Palmer Eugene O’Neill Review…………….….12 Contributors…………………………...20 [email protected] Robert Richter [email protected] EX OFFICIO IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT The Eugene O’Neill Society Kurt Eisen [email protected] Founded 1979 • eugeneoneillsociety.org THE EUGENE O’NEILL REVIEW A nonprofit scholarly and professional organization devoted to the promotion and Editor: William Davies King [email protected] study of the life and works of Eugene O’Neill and the drama and theatre for which NEWSLETTER his work was in large part the instigator and model. -

FEMINISM of ALICE PAUL in IRON JAWED ANGELS MOVIE 1Firdha Rachman, 2Imam Safrudi Sastra Inggris STIBA NUSA MANDIRI Jl. Ir. H. Ju

FEMINISM OF ALICE PAUL IN IRON JAWED ANGELS MOVIE 1Firdha Rachman, 2Imam Safrudi Sastra Inggris STIBA NUSA MANDIRI Jl. Ir. H. Juanda No. 39 Ciputat. Tangerang Selatan [email protected] ABSTRACT Most of women in the world are lack support for fundamental functions of a human life. They are less well nourished than men, less healthy, more vulnerable to physical violence and sexual abuse. They are much less likely than men to be literate, and still less likely to have professional or technical education. The objectives of this analysis are: (1) to know the characterization of Alice Paul as the main Character in Iron Jawed Angels Movie. (2) to find out the type of feminism in the main character. The method used is descriptive qualitative method and library research to collect the data and theories. The result of this thesis indicated that Alice has some great characterization such as smart, independent, brave, a great motivator, and educated woman. The type of her feminism in the main character is Liberal Feminism. Keywords: Feminism, Characterization, IRON JAWED ANGELS Movie I. INTRODUCTION the laws were made by men, women were not Most of women in the world are lack allowed to vote. They were always seen as a support for fundamental functions of a human certain role and known as the property. It life. They are less well nourished than men, less means, men thought women had things to do healthy, more vulnerable to physical violence like taking care of their children. It was difficult and sexual abuse. They are much less likely for women to fit in the society. -

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements By Laura K. Nelson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Robin Einhorn Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Laura K. Nelson 1 Abstract The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements by Laura K. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair This dissertation challenges the widely accepted historical accounts of women's movements in the United States. Second-wave feminism, claim historians, was unique because of its development of radical feminism, defined by its insistence on changing consciousness, its focus on women being oppressed as a sex-class, and its efforts to emphasize the political nature of personal problems. I show that these features of second-wave radical feminism were not in fact unique but existed in almost identical forms during the first wave. Moreover, within each wave of feminism there were debates about the best way to fight women's oppression. As radical feminists were arguing that men as a sex-class oppress women as a sex-class, other feminists were claiming that the social system, not men, is to blame. This debate existed in both the first and second waves. Importantly, in both the first and the second wave there was a geographical dimension to these debates: women and organizations in Chicago argued that the social system was to blame while women and organizations in New York City argued that men were to blame.