Something in Our Souls Above Fried Chicken Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Iron Jawed Angels

Voting Rights Under Attack: An NCJW Toolkit to Protect the Vote Film Screening and Discussion: Iron Jawed Angels Films can offer a good basis for discussion and further understanding of important subjects. A film program that includes a screening, facilitated discussion, and perhaps even a speaker, can be an excellent way for NCJW members and supporters to learn more about and get involved in an issue. Iron Jawed Angels, film by Katja von Garnier: In the early twentieth century, the American women’s suffrage movement mobilized and fought to grant women the right to vote. Watch Alice Paul (Hilary Swank) and Lucy Burns (Frances O’Connor) as they fight for women’s suffrage and revolutionize the American feminist movement. Preparation for the Film Screening: Ñ Remind participants to be prepared to discuss how the film relates to NCJW’s mission. Ñ Encourage participants to bring statistics and information about voter rights in your community. Ñ Confirm location and decide who is bringing snacks and beverages. Ñ Ensure a facilitator is prepared to ask questions and guide discussion. Ñ Download and print copies of NCJW’s Promote the Vote. Protect the Vote Resource Guide. Discussion Questions to Consider: Ñ Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Women’s Party conducted marches, picketed the White House, and held rallies. What ways can you mobilize and influence your local, state, and federal elected officials? Ñ Lucy Burns discusses the “dos and don’ts” of lobbying, which include knowing the background of the member, being a good listener, and not losing your temper. Do you think these www.ncjw.org June 2016 4 Voting Rights Under Attack: An NCJW Toolkit to Protect the Vote rules have changed in the past 100 years? If so, how? What other “dos and don’ts” can you think of? Ñ How did the film portray racism within the women’s suffrage movement? How did racism linger in the feminist movement? Ñ In the film, the methods of the National Women’s Party and the National American Women’s Suffrage Association are contrasted. -

“A Luncheon for Suffrage

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 16 (2012) Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, 75-90 A LUNCHEON FOR SUFFRAGE: THEATRICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF HETERODOXY TO THE ENFRANCHISEMENT OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN NOELIA HERNANDO REAL Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Received 27th September 2012 Accepted 14th January 2013 KEYWORDS: Heterodoxy; US woman suffrage; theater; Susan Glaspell; Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Marie Jenney Howe; Paula Jakobi; George Middleton; Mary Shaw. PALABRAS CLAVE: Heterodoxy; sufragio femenino en EEUU; teatro; Susan Glaspell; Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Marie Jenney Howe; Paula Jakobi; George Middleton; Mary Shaw. ABSTRACT: This article explores and discusses the intertextualities that are found in selected plays written in the circle of Heterodoxy in the 1910s, the Greenwich Village-based radical club for unorthodox women. The article examines some of the parallels that can be found in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Something to Vote For, George Middleton’s Back of the Ballot, Mary Jenney Howe’s An Anti-Suffrage Monologue and Telling the Truth at the White House, written in collaboration with Paula Jakobi, Mary Shaw’s The Parrot Cage and The Woman of It, and Susan Glaspell’s Trifles, Bernice, Chains of Dew and Woman’s Honor. The works are put in the context of the national movement for woman suffrage and focuses on the authors’ arguments for suffrage as well as on their formal choices, ranging from realism to expressionism, satire and parody. RESUMEN: El presente artículo explora y discute las intertextualidades que se encuentran en una selección de obras escritas en el círculo de Heterodoxy, el club para mujeres no-ortodoxas con base en Greenwich Village, en la década de 1910. -

Women's Suffrage Reading List

Women’s Suffrage Reading List BOOKS FOR CHILDREN How Women Won the Vote: Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and their Big Idea Susan Campbell Bartoletti | J 324.6 BAR A history of the iconic first women's march in 1913 and the suffragists who led the way to passing the 19th amendment, ideal for readers ages 8 to 12. What is the Women’s Rights Movement? Deborah Hopkinson | J 305.420973 HOP Tailored for an elementary school audience, this entry in the popular “What is” series provides an engaging overview of the women’s rights movement in the United States, from colonial times to the 20th century and beyond. Around America to Win the Vote Mara Rockliff | J PIC ROC This whimsical picture book recounts the adventures of two very determined women. In April 1916, Nell Richardson and Alice Burke set out on a bumpy, muddy, unmapped journey ten thousand miles long with a message for Americans all across the country: Votes for Women! Lillian’s Right to Vote Jonah Winter | J 324.620973 WIN An elderly woman embarks on the long uphill trek to her polling place and reflects on the arduous steps taken by her forebears and herself to bring her there. This book provides needed context that the 19th Amendment applied only to white women, and it would take another 45 years for Black women to gain the right to vote. Roses and Radicals: The Epic Story of How American Women Won the Right to Vote Susan Zimet & Todd Hasak-Lowy | J 324.6 ZIM The story of women's suffrage is epic, frustrating, and as complex as the women who fought for it. -

FEMINISM of ALICE PAUL in IRON JAWED ANGELS MOVIE 1Firdha Rachman, 2Imam Safrudi Sastra Inggris STIBA NUSA MANDIRI Jl. Ir. H. Ju

FEMINISM OF ALICE PAUL IN IRON JAWED ANGELS MOVIE 1Firdha Rachman, 2Imam Safrudi Sastra Inggris STIBA NUSA MANDIRI Jl. Ir. H. Juanda No. 39 Ciputat. Tangerang Selatan [email protected] ABSTRACT Most of women in the world are lack support for fundamental functions of a human life. They are less well nourished than men, less healthy, more vulnerable to physical violence and sexual abuse. They are much less likely than men to be literate, and still less likely to have professional or technical education. The objectives of this analysis are: (1) to know the characterization of Alice Paul as the main Character in Iron Jawed Angels Movie. (2) to find out the type of feminism in the main character. The method used is descriptive qualitative method and library research to collect the data and theories. The result of this thesis indicated that Alice has some great characterization such as smart, independent, brave, a great motivator, and educated woman. The type of her feminism in the main character is Liberal Feminism. Keywords: Feminism, Characterization, IRON JAWED ANGELS Movie I. INTRODUCTION the laws were made by men, women were not Most of women in the world are lack allowed to vote. They were always seen as a support for fundamental functions of a human certain role and known as the property. It life. They are less well nourished than men, less means, men thought women had things to do healthy, more vulnerable to physical violence like taking care of their children. It was difficult and sexual abuse. They are much less likely for women to fit in the society. -

2008-2009 Annual Report July 1, 2008-June 30, 2009

2008-2009 ANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2008-JUNE 30, 2009 KATHLEEN McHUGH DIRECTOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Director’s Overview 3 Staff, Advisory Committee, and Faculty Affiliates 5 Research and Programming 10 CSW Research 12 Faculty Research 16 Graduate Student Research 21 Undergraduates and Independent Scholars 27 List of Awards and Grants Recipients 29 Publications and Publicity 34 Faculty and Student Involvement 40 Administration 45 Space 45 Budget 46 Appendices 1. Meet the Authors 48 2. Events Summary 49 3. State of the Union 58 4. Thinking Gender Conference Program 62 5. Travel Grant Recipients 68 6. Research Scholars 69 7. Bibliography of Publications Enabled by CSW Support 72 8. Contents of CSW Newsletter 74 9. Podcast List 78 10. Contents of Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 2008-2009 83 11. Awards and Grants Committees 86 12. Staff and Personnel 87 13. Fiscal Summary 89 14. Development Funds 91 15. Comments From CSW Survey Respondents 92 16. Survey Summary 102 2 DIRECTOR’S OVERVIEW Academic year 2008-09 was the fourth of my directorship. This year, I sought to expand CSW’s research and fundraising capacities, having met the goals I set for the first three years of my directorship. I drew these initial goals from the guidelines and suggestions made in CSW’s Fifteen Year Review, completed in 2005 just before I became director. The review strongly recommended the separation of CSW from the Women’s Studies Program (their fusion, the reviewers observed, was operating “to the detriment of both programs”) and called for CSW to sharpen its focus on research; enhance its publication activities; and cultivate the participation of junior faculty. -

Thinking Gender

THINKING GENDER 24th Annual Graduate Student Research Conference Friday, February 7, 2014 7:30 am to 6:30 pm, UCLA FACULTY CENTER PROGRAM OVERVIEW 7:30 – 8:30 am Registration Opens/Breakfast 8:30 – 9:50 am Session 1 10:05 – 11:25 am Session 2 11:30 am – 12:45 pm Lunch Break 1:00 – 2:30 pm Plenary Session: Somatic Pleasures And Traumas: Seduction, Senses, And Sexuality, moderated by Kathleen McHugh 2:45 – 4:05 pm Session 3 4:20 – 5:40 pm Session 4 5:45 – 6:30 pm Reception Thinking Gender is an annual public conference highlighting graduate student research on women, sexuality, and gender across all disciplines and historical periods. *** Session 1: 8:30-9:50 AM HACIENDA CONTROVERSY, CONTRACTS, LAWS AND POLICY Moderator: Juliet Williams, Gender Studies, UCLA Ian M. Baldwin, History, UNLV, Housing the Liberation: Fair Housing and the Opening of American “Families” in Gay Liberation Los Angeles Jennifer M. Moreno, History and Theory of Contemporary Art, San Francisco Art Institute, Ethical Contradictions: The HRC’s Symbol of Equality and the Impossibility of Queer Desire Kacey Calahane, History, San Francisco State U, Women against Women’s Rights: Anti- Feminism, Reproductive Politics, and the Battle Over the ERA 1 Narges Pisheh, Center for Near Eastern Studies, UCLA, Muta: Fixed-term Islamic Marriage and Intimacy Politics SIERRA POLICING BODIES: SEX, VIOLENCE, AND THE STATE Moderator: Tzili Mor, School of Law Visiting Scholar, UCLA Ashley Green, Women’s Studies, San Diego State U, Hey Girl, Did You Know?: The Impact of Race and Class on -

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

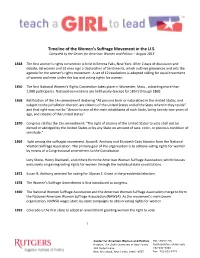

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

Women's Movement: the History and Timeline 1500S

WST 101: Women’s Studies Learning Unit 1: Handout Women’s Movement: The History and Timeline 1500s – 1600s Our country was founded by a group from England called the Puritans. They were known to be so religiously conservative that they were asked to leave England for the new world. Think about the story you know of Thanksgiving. This was the foundation for our country and for the status and treatment of women in our country. The Puritans believed: Social order lay in the authority of husband The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth over wife, parents over children, and masters by Jennie A. Brownscombe over servants. Women could not own property and lost their civil birth identity when they became married. A woman’s salvation (place in heaven) was ensured by the goodness exhibited in her children. The home was the only place women were allowed to exercise discipline. In public, they deferred to their husband or the patriarchy of the church and community. 1701 The first sexually integrated jury hears cases in Albany, New York. This was a social change despite the fact that women were generally excluded from civic responsibilities and legal activities of the time. 1769 The American colonies based their laws on English Common Law, which is what they were familiar with. English Common Law stated: “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person under law. The very being and legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least incorporated into that of her husband under whose wing and protection she performs everything.” 1774 Colonial delegates – all men – gather to discuss the treatment they were receiving from their Mother Country (England). -

A History of Veganism from 1806

1 World Veganism – past, present, and future By John Davis, former IVU Manager and Historian A collection of blogs © John Davis 2010-12 Introduction This PDF e-book is about 8mb, 219 pages A4, (equivalent to 438 page paperback book), so I strongly recommend that you save a copy to your own disk, then open it in the Adobe Acrobat Reader. That way, you won’t have to download it all again if you want to read more of it sometime later. Creating this as a PDF e-book has several advantages, especially if you are reading this on a device connected to the internet. For example: - in the blog about interviews on SMTV, just click on the links to watch the videos - in the bibliography click to read a complete scan of an original very old book. - on the contents page click a link to go direct to any item, then click ‘back to top’. - you can also, of course, use other features such as search, zoom etc. etc. - a great advance on printed books… It should work on any device, though an ipad/tablet is ideal for this as there are lots of big colour photos, or on smart-phones try rotating for best results, on a larger computer monitor try view/page display/two up, to read it like a book. The blogs were posted weekly from February 2010 to December 2012 and each is self- contained, with the assumption that readers might not have seen any of the others. So feel free to start anywhere, and read them in any order, no need to read from the beginning.