Download for the Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foodservice Toolkit Potatoes Idaho® Idaho® Potatoes

IDAHO POTATO COMMISSION Foodservice Table of Contents Dr. Potato 2 Introduction to Idaho® Potatoes 3 Idaho Soil and Climate 7 Major Idaho® Potato Growing Areas 11 Scientific Distinction 23 Problem Solving 33 Potato Preparation 41 Potato101.com 55 Cost Per Serving 69 The Commission as a Resource 72 Dr. Potato idahopotato.com/dr-potato Have a potato question? Visit idahopotato.com/dr-potato. It's where Dr. Potato has the answer! You may wonder, who is Dr. Potato? He’s Don Odiorne, Vice President Foodservice (not a real doctor—but someone with experience accumulated over many years in foodservice). Don Odiorne joined the Idaho Potato Commission in 1989. During his tenure he has also served on the foodservice boards of United Fresh Fruit & Vegetable, the Produce Marketing Association and was treasurer and then president of IFEC, the International Food Editors Council. For over ten years Don has directed the idahopotato.com website. His interest in technology and education has been instrumental in creating a blog, Dr. Potato, with over 600 posts of tips on potato preparation. He also works with over 100 food bloggers to encourage the use of Idaho® potatoes in their recipes and videos. Awards: The Packer selected Odiorne to receive its prestigious Foodservice Achievement Award; he received the IFEC annual “Betty” award for foodservice publicity; and in the food blogger community he was awarded the Camp Blogaway “Golden Pinecone” for brand excellence as well as the Sunday Suppers Brand partnership award. page 2 | Foodservice Toolkit Potatoes Idaho® Idaho® Potatoes From the best earth on Earth™ Idaho® Potatoes From the best earth on earth™ Until recently, nearly all potatoes grown within the borders of Idaho were one variety—the Russet Burbank. -

Starter Main Course Dessert Healthy-Drink Healthy-Snack Menu

Menu Estonia Starter Salad Main Course Dessert Healthy-Drink Kama Healthy-Snack BLACK BREAD WITH BALTIC SPRATS Healthy Recipes Salad Ingredients Salad Chopped tomatoes Ingredients Dressing Celery Olive oil Spring onions Balsamic vinegar or Sliced cucumbers fresh-squeezed lemo- Sliced radishes ne juice Small amount of cheese Fresh spices Tuna Cauliflower Broccoli Carrots Preparation Add chopped tomatoes, celery, spring onions, sliced cucumbers and sliced radishes. Add a small amount of cheese. Cheese is high in calories and fat, so use sparingly. Add tuna. Then combine a variety of vegetables like cauliflower, broccoli, carrots. Toss the vegetable combination in- to the salad. Top off your salad by sprinkling on a homemade dressing (olive oil is very good for you when not heat- ed), balsamic vinegar or fresh-squeezed lemon juice. For a different taste, throw in some fresh spices like dill, oregano, basil or garlic. Page 2 ESTLAND Healthy Body Healthy Mind Main Course Ingredients sauer kraut potatoes, peeled beef roast different spices (pepper, mustard, etc.) salt water, 1 cup mustard, for serving Preparation Preheat oven to 180 °C. Place the beef on a roasting pan, rub with spices and salt. Add the water and put it into the oven for 120-160 mins. While the beef is cooking, boil the potatoes in a salted water and heat up the sauerkraut. When ready, set the table and call everyone in for the meal! The meat will taste best with a touch of mustard. You can drink whatever beverage you prefer. Page 3 Healthy Body Healthy Mind ESTLAND Dessert Ingredients 100 gr butter 1 dl dark Muscovado sugar 3 spoonful kama flour 3 dl oatmeal (cereals) 1 egg 100 gr white chocolate Preparation Mix the sugar, egg, cereals and kama flour with butter (butter has to be in room temperature). -

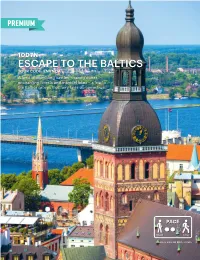

Escape to the Baltics

PREMIUM 10D7N ESCAPE TO THE BALTICS TOUR CODE: ENVNOA A land of crumbling castles, soaring dunes, enchanting forests and magical lakes – a trip to the Baltics proves that fairy tales do come true. 123RF AERIAL VIEW OF RIGA, LATVIA PHOTO: 34 Northern Europe | EU Holidays Helsinki HIGHLIGHTS Tallinn LITHUANIA 2 Estonia VILNIUS • Vilnius Cathedral Basilica Flight path Parnu • Pilies Street Traverse by coach • St. Anne’s, Bernardine’s and St. Michael’s Traverse by cruise Churches Featured destinations 2 • Orthodox Church Overnight stays 1 2 3 Riga Latvia • Gate of Dawn • Vilnius University Lithuania LATVIA 2 RIGA • Dome Cathedral (entrance included) Vilnius • St. Peter’s Tower • Old Guild Houses Poland • Riga Castle 1 • Swedish Gate Warsaw ESTONIA TALLINN • Old Town tour • Gothic Town Hall • Toompea • Alexander Nevski Cathedral DAY 1 among bogs, stumble upon old Soviet ruins HOME → HELSINKI like an abandoned submarine station and see DELICACIES Meals on Board exquisite centuries-old manor houses. Assemble at the airport and take-off to the Meal Plan city of Helsinki, Finland’s southern capital, DAY 4 7 Breakfasts, 3 Lunches, 4 Dinners sits on a peninsula in the Gulf of Finland. TALLINN → PÄRNU → RIGA Breakfast, Latvian Dinner Specialities DAY 2 Join a short sightseeing tour in Pärnu, the Estonian Cuisine HELSINKI TALINN Estonian resort town. The summer capital, Lativan Cuisine → Meals on Board, Estonian Dinner Pärnu, is a town of parks, alleys, beaches, Lithuanian Cuisine Upon arrival, free at leisure till time to board a warm shallow waters and health spas ferry to Tallinn, Estonia’s capital on the Baltic offering various curative treatments including Sea, is the country’s cultural hub. -

A Plant-Based Cook's Guide to Potatoes

A Beginner's Guide to Potatoes By April 28 2021 Everything you need to know about one of the best-loved, most versatile foods in the world: potatoes. With potato selection and storage tips, basic cooking methods, blueprint recipes, and a rundown of which varieties are best for what, this guide has got you covered. Are Potatoes Vegetables? In the field or garden, a potato is a tuberous root vegetable. It’s a member of the nightshade family of plants along with tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers. Nutritionally speaking, potatoes are considered a carbohydrate because their flesh is primarily made up of starch. Potatoes vs. Sweet Potatoes Sweet potatoes and yams are also root vegetables, though they belong to a different botanical family altogether. Sweet potatoes are very similar to potatoes when it comes to nutritional makeup, but they have about 50 percent more fiber than potatoes. Are Potatoes Healthy? Potatoes sometimes get a bad rap thanks to their association with greasy french fries and potato chips. But it’s not the potatoes that make those foods unhealthy; it’s the oil and salt. Potatoes, in and of themselves, are as nutritious as they are delicious, an incredibly healthful source of starchy satisfaction (which is why they’re a foundation of a whole-food, plant-based diet). And no, carb-rich whole plant foods such as potatoes will not make you gain weight, as long as they’re prepared healthfully. Can You Eat Them Raw? No, you can’t eat potatoes raw—but why would you want to? If you’ve ever crunched into an undercooked potato (it happens), then you know raw potatoes are mealy and bitter. -

Best of British Best

Foo d and Tr a vel June 2011 Issue No 137 Estonia, Suffolk, Mongolia, Osijek, Mainz, Toulouse, Seaside Rentals vel June 2011 Issue No 137 Estonia, Suffolk, Mongolia, Osijek, Mainz, Toulouse, , Food Festivals, Raymond Blanc, Broad Beans WORLD FOOD from China, Estonia and Morocco Raymond Blanc Horseback adventures in shares his kitchen secrets Mongolia Why it's worth indulging in Taste the experience – taste Taste CITY BREAKS California wine France, Germany and Croatia £3.95 BEST OF BRITISH FOOD FESTIVALS GOURMET TRAVEL SEASIDE RENTALS SAVING HONEY JUNE 2011 001_Food cover repro OPTION.indd 1 15/4/11 15:35:36 SEAN - PLEASE PLACE NEW COVERS THX 26 On the cover 28 Estonia 38 Mongolia WO RL D FOOD from China, Estonia and Morocco Horseback adventures in M o n g o l i a 47 Raymond Blanc 65 Best of British s s Raymond Blanc shares his kitchen secrets WO RL D FOOD from China, Estonia a n d Mo r o c c o Raymond Blanc 74 Seaside rentals Horseback adventures in shares his kitchen secrets Why it's worth indulging in Mo n g o l i a Why it's worth indulging in California w i n e C I T Y BR EAKS California wine France, Germany and Croatia C I T Y BR EAKS £3.95 £3.95 France, Germany and Croatia 93 City breaks BEST OF BRITISH BEST OF BRITISH F O O D FE S T I V A L S GOU RM E T T RAVEL SE A S I D E RE N T A L S SAVIN G H O N E Y F O O D FESTIVALS GOU RM E T T RAVEL SE A S I D E RENTALS SAVIN G H O N E Y JUNE 2011 JUNE 2011 113 California wine 66 t t Regulars Features 7 Arrivals 28 Baltic flavours 00 The latest food, drink and travel Francis Pearce samples -

Das Große MENÜ-Regisfer 1

Das große MENÜ-Regisfer 1. Alphabetisches Stichwortverzeichnis ln diesem Stichwortverzeichnis finden Sie in alphabetischer Reihenfolge alle Rezepte, Warenkunden und Tips aus 10 MENÜ-Bänden. Die erste Zahl hinter dem Stichwort gibt die Bandzahl an, die zweite Zahl die Seitenzahl. Fettgedruckte Seitenzahlen weisen auf einen Tip hin. Ein (W) hinter der Seitenzahl be deutet, daß es sich hier um eine Warenkunde handelt, ein (H) steht für Hinweis und (PS) weist auf einen Rezept-Nachtrag hin. Albertkekse 1/13 Ananaskraut 1/29 - s. auch Alcazar-Torte 1/14 Ananasmelone, Horsd’cBüvre 4/297 (W) Alexander-Cocktail 1/15 s. Melone 6/310 (W) - s. auch Sachgrup Aachener Printen 1/1 Alice-Salat 1/15 6/311 penregister Aal aus der Provence 1/1 Alicot, s. Puterra Ananas-Partyspieße 1/30 Vorspeisen - blau 1/1 gout kanadisch 8/75 Ananas-Pumpernik- - s. auch Schweden - Frikassee von 3/298 Allgäuer Käse kel-Dessert 1/30 platte 9/287 - gebraten 1/2 spatzen 1/16 Ananas-Salat auf Aperitif An isette 1/41 - gekocht, s. Aal - Käsesuppe 1/16 Äpfeln 1/30 Apfel, Adams- 1/11 schnitten ait- - Suppenknödel 1/17 - Colmar 1/32 Äpfel »Bolette« 1/42 hoiländisch 1/7 Altdeutscher Topf 1/20 - Käse- 5/222 - bosnisch 1/42 - geräuchert 1/2 Altenglischer Punsch 1/20 - Zwiebel- 10/300 - bulgarisch 1/43 - grün auf flämi Altholländische Ananas-Schnitzel 1/32 - Eierkuchen mit 2/337 sche Art 1/4 Aalschnitten 1/7 Ananas-Schokolade - Eskimo- 3/70 - häuten 1/4 Alufolie 3/78 Schnitten 1/33 - flambiert» 1/43 1/6 Aluko Chop, s. -

To View Online Click Here

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: What I love about the little town of Harmi, Estonia, is that it has a lot of heart. Its residents came together to save their local school, and now it’s a thriving hub for community events. Harmi is a new partner of our Grand Circle Foundation, and you’ll live a Day in the Life here, visiting the school and a family farm, and sharing a farm-to-table lunch with our hosts. I love the outdoors and I love art, so my walk in the woods with O.A.T. Trip Experience Leader Inese turned into something extraordinary when she led me along the path called the “Witches Hill” in Lithuania. It’s populated by 80 wooden sculptures of witches, faeries, and spirits that derive from old pagan beliefs. You’ll go there, too (and I bet you’ll be as surprised as I was to learn how prevalent those pagan practices still are.) I was also surprised—and saddened—to learn how terribly the Baltic people were persecuted during the Soviet era. -

Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-180 ISSUE 16, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Copyright Page Issue 16, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 16, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Table of Contents 1. -

2007 Recipe Index. a Fresh Borlotti Bean & Spring Seared Sirloin Salad with Barley, Apricots Vegetable Soup

annual recipe index. 2007 recipe index. a fresh borlotti bean & spring seared sirloin salad with barley, apricots vegetable soup ............................Sep:162 grapes & sumac ............................Mar:85 apricot & apple charlotte ..................Aug:71 garlic green beans ............................May:67 soy beef with tatsoi salad ...............Mar:132 baked apricot chicken with parsnip Greek bean & silverbeet stew ........Mar:138 spicy beef, olive & onion pie ............. Jun:10 and pumpkin ............................... Apr:136 green bean & asparagus salad steak & mushroom pie .....................May:38 baked lamb & apricot couscous...... Jun:78 with sesame dressing ....................Oct:78 steak Diane ...................................... Jun:106 artichoke pesto ....................................May:106 green beans with basil dressing ....Dec:125 steak tagliata with roast tomatoes ...May:68 asparagus green beans with hot feta dressing .. Feb:98 steak with anchovy asparagus, artichoke & grape tomato green beans with red onion and & red wine butter .......................... Jun:88 salad with cottage cheese......... .Nov:206 redcurrants ................................. Apr:118 steak with lemon pepper potatoes . Feb:135 asparagus, ham & mascarpone grilled whiting with summer beef salad ......................... Feb:130 tarts ............................................ Dec:154 Mediterranean bean salad ......... Feb:133 teriyaki beef & beans ........................ Feb:84 asparagus risotto ............................Nov:191 -

Toomas Hendrik Ilves

Dec.9 - Dec.11, 2011 Vienna – Austria Toomas Hendrik Ilves President of the Republic of Estonia President of the Republic of Estonia Toomas Hendrik Ilves was born on the 26th of December, 1953, in the Swedish capital Stockholm, and has spent much of his life living and working in a total of five different countries. The Estonian values prevalent in his childhood home, the education gained at one of the US ’s best universities, the jobs connected with Estonia’s present and future over the last quarter of the century – this is what has shaped Toomas Hendrik Ilves as a person and president of a small European country in the 21 st century. Born on December 26, 1953 in Stockholm, Kingdom of Sweden Married to Evelin Ilves Children: son Luukas Kristjan (1987), daughters Juulia (1992) and Kadri Keiu (2003) Education 1978 Pennsylvania University (USA), MA in psychology 1976 Columbia University (USA), BA in psychology Career and public service 2006- President of the Republic of Estonia 2004-2006 Member of the European Parliament 2002-2004 Member of the Parliament of the Republic of Estonia 1999-2002 Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Estonia 1998 Chairman, North Atlantic Institute 1996-1998 Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Estonia 1993-1996 Ambassador of the Republic of Estonia to the United States of America, Canada, and Mexico 1988-1993 Head of the Estonian desk, Radio Free Europe in Munich, Germany 1984-1988 Analyst and researcher for the research unit of Radio Free Europe in Munich, Germany 1983-1984 Lecturer in Estonian Literature and Linguistics, Simon Fraser University, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, Vancouver, Canada 1981-1983 Director and Administrator of Art, Vancouver Arts Center, Canada 1979-1981 Assistant Director and English teacher, Open Education Center, Englewood, New Jersey, USA 1974-1979 Research Assistant, Columbia University department of Psychology, USA Publications Compilation of speeches and writings from 1986-2006: "Eesti jõudmine. -

Hospitality Asia 2019 Issue • Volume 1 Pp 8897/05/2013(032307) • Mci (P) 072/08/2019

HOSPITALITY ASIA HOSPITALITY 2019 ISSUE • VOLUME 1 2019 ISSUE • VOLUME PP 8897/05/2013(032307) • MCI (P) 072/08/2019 hospitality asia ~ 2019 Issue Volume 1 Page C Hot Stamp C M Y K M-iClean H Welcome to dishwashing paradise A machine that works like magic, making dishwashing so quick and easy that it feels like being in paradise! Welcome to the world of professional warewashing technology made by MEIKO. The M-iClean H is the latest leap forward in warewashing excellence from the experts in clean solutions. As well as being fantastically easy to use, it also offers outstanding efficiency and sustainability. Check it out for yourself! www.meiko-asia.com hospitality asia ~ 20192018 Issue Volume 12 Page PageIFCC31 C C M Y K LHPD & LSP Hapa Magazine Generic Ad 205mm(W) x 255mm(H) - Mar 2019_OL.pdf 1 25/03/2019 3:38 PM hospitality asia ~ 2019 Issue Volume 1 PagePage 1 1 C M Y K PubsNote A Time For Change The greatest inevitability in life is change. While some claim that time changes things, in reality it is us who must change. Here, we like to lead rather than follow, to set the trends and to create the change. As such, we are proud to announce a name change to HAPA Group Sdn. Bhd. to surge us forward. The name change comes as we celebrate 25 years of serving the industry and I am proud that we have been able to do this and to be recognised as a leader in all various facets of our operations. -

CMN / EA International Provider Network HOSPITALS/CLINICS

CMN / EA International Provider Network HOSPITALS/CLINICS As of March 2010 The following document is a list of current providers. The CMN/EA International Provider Network spans approximately 200 countries and territories worldwide with over 2000 hospitals and clinics and over 6000 physicians. *Please note that the physician network is comprised of private practices, as well as physicians affiliated with our network of hospitals and clinics. Prior to seeking treatment, Members must call HCCMIS at 1-800-605-2282 or 1-317-262-2132. A designated member of the Case Management team will coordinate all healthcare services and ensure that direct billing arrangements are in place. Please note that although a Provider may not appear on this list, it does not necessarily mean that direct billing cannot be arranged. In case of uncertainty, it is advised Members call HCCMIS. CMN/EA reserves the right, without notice, to update the International Provider Network CMN/EA International Provider Network INTERNATIONAL PROVIDERS: HOSPITALS/CLINICS FacilitY Name CitY ADDRess Phone NUMBERS AFGHanistan DK-GERman MedicaL DiagnOstic STReet 66 / HOUse 138 / distRict 4 KABUL T: +93 (0) 799 13 62 10 CenteR ZOne1 ALBania T: +355 36 21 21 SURgicaL HOspitaL FOR ADULts TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 T: +355 36 21 21 HOspitaL OF InteRnaL Diseases TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 T: +355 36 21 21 PaediatRic HOspitaL TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 ALGERia 4 LOT. ALLIOULA FOdiL T: +213 (21) 36 28 28 CLiniQUE ChahRAZed ALgeR CHÉRaga F: +213 (21) 36 14 14 4 DJenane AchaBOU CLiniQUE AL AZhaR ALgeR