University of Warwick Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lie of the Land' by Toby Whithouse - TONE DRAFT - 22/11/16 1 PUBLIC INFORMATION FILM

DOCTOR WHO SERIES 10 EPISODE 8 "X" by Toby Whithouse TONE DRAFT (DRAFT TWO) 22/11/16 (SHOOTING BLOCK 6) DW10: EP 8 'The Lie of the Land' by Toby Whithouse - TONE DRAFT - 22/11/16 1 PUBLIC INFORMATION FILM. 1 Space. The sun rising over the peaceful blue Earth. VOICE OVER The Monks have been with us from the beginning. Primordial soup: a fish heaves itself from the swamp, its little fins work like pistons to drag itself up the bank, across the sandy earth. The most important and monumental struggle in the planet’s history. It bumps into the foot of a Monk, waiting for it. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They shepherded humanity through its formative years, gently guiding and encouraging. Cave paintings: primitive man. Before them, what can only be a Monk. It holds a spear, presenting it to the tribe of men. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) Like a parent clapping their hands at a baby's first steps. Another cave painting: a herd of buffalo, pursued by the men, spears and arrows protruding from their hides. Above and to the right, watching, two Monks. Benign sentinels. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They have been instrumental in all the advances of technology and culture. Photograph: Edison, holding a lightbulb. The arm and shoulder of a Monk next to him, creeping into the frame. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They watched proudly as man invented the lightbulb, the telephone, the internet... Photograph: the iconic shot of Einstein halfway through writing the equation for the theory of relativity on a blackboard. -

Mcsporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction

McSporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the winter in: myth revision and the winter solstice in fantasy fiction. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5812/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction Cathy McSporran Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature, University of Glasgow Submitted October 2007 @ Cathy McSporran 2007 Abstract Letting the Winter In: Myth-Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction This is a Creative Writing thesis, which incorporates both critical writing and my own novel, Cold City. The thesis explores 'myth-revision' in selected works of Fantasy fiction. Myth- revision is defined as the retelling of traditional legends, folk-tales and other familiar stories in such as way as to change the story's implied ideology. (For example, Angela Carter's 'The Company of Wolves' revises 'Red Riding Hood' into a feminist tale of female sexuality and empowerment.) Myth-revision, the thesis argues, has become a significant trend in Fantasy fiction in the last three decades, and is notable in the works of Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman and Philip Pullman. -

A Young-Old Face : out with the New and in with the Old Hewett, RJ

A young-old face : out with the new and in with the old Hewett, RJ Title A young-old face : out with the new and in with the old Authors Hewett, RJ Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/34862/ Published Date 2018 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. PART ONE THE DOCTOR AND HIS COMPANIONS 1 1 A Young-Old Face Out with the New and in with the Old in Doctor Who Richard Hewett Introduction ‘I approve of your new face, Doctor - so much more like mine.’ This line, spoken by the now ancient, enervated and seemingly dying Davros in ‘The Magician’s Apprentice’, is just one of many age-related barbs directed at the Twelfth Doctor during Peter Capaldi’s reign, serving as a constant reminder that the Time Lord is no longer (if, indeed, his on-screen self ever was)1 a young man. Throughout his tenure, friends and foes alike highlighted the latest incarnation’s wrinkled, somewhat cadaverous visage, grey hair, and scrawny body, the Doctor being variously described as a ‘desiccated man crone’ (‘Robot of Sherwood’), a ‘grey-haired stick insect’ (‘Listen’), and a ‘skeleton man’ (‘Last Christmas’). -

The Fellowship of the Ring

iii THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING being the first part of THE LORD OF THE RINGS by J.R.R. TOLKIEN Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky, Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone, Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die, One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie. One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie. CONTENTS Note on the Text ix Note on the 50th Anniversary Edition xviii Foreword to the Second Edition xxiii Prologue Concerning Hobbits, and other matters 1 book one I A Long-expected Party 27 II The Shadow of the Past 55 III Three is Company 85 IV A Short Cut to Mushrooms 112 V A Conspiracy Unmasked 128 VI The Old Forest 143 VII In the House of Tom Bombadil 161 VIII Fog on the Barrow-downs 176 IX At the Sign of The Prancing Pony 195 X Strider 213 XI A Knife in the Dark 230 XII Flight to the Ford 257 book two I Many Meetings 285 II The Council of Elrond 311 III The Ring Goes South 354 viii contents IV A Journey in the Dark 384 V The Bridge of Khazad-duˆm 418 VI Lothlo´rien 433 VII The Mirror of Galadriel 459 VIII Farewell to Lo´rien 478 IX The Great River 495 X The Breaking of the Fellowship 515 Maps 533 Works By J.R.R. -

Translation Rights List FICTION May 2019

Translation Rights List Including FICTION May 2019 Contents • Rights Department p.3 • Little, Brown Imprints p.4 • General p.5 • Literary p.15 • Commercial p.20 • Crime, Mystery & Thriller p.26 • Sci-Fi & Fantasy p.36 • Rights Representatives p.44 Key • Rights sold displayed in parentheses indicates that we do not control the rights • An asterisk indicates a new title since previous Rights list • Titles in italics were not published by Little, Brown Book Group. 2 Rights Department ANDY HINE Rights Director Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America and the Baltic States [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6545 KATE HIBBERT Rights Director USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East, the Netherlands, Flemish Belgium and the Indian Subcontinent [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6619 HELENA DOREE Senior Rights Manager France, French Belgium, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Macedonia [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6598 HENA BRYAN Rights Trainee [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 0693 Little, Brown Book Group Follow us on Twitter: Carmelite House @LBBGRights 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ UNITED KINGDOM 3 Little, Brown Imprints 4 General Highlights INHERITANCE A LINE OF DESIRE LIBERATION AFTER THE END 5 * THE BOOK OF KOLI by M.R. Carey Contemporary Fiction | Orbit | 416pp | april 2020 | Korea: Duran Kim | Japan: Japan Uni This is the tale of Koli – a young man who lives in the village of Mythen Rood. This is a future Britain, but one which is barely recognisable now. -

That Attempts to Illustrate How Environmental Education and Basis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 319 SO 024 144 AUTHOR Fien, John, Ed. TITLE Teaching for a Sustainable World. Environmental and Development Education Project for Teacher Education. INSTITUTION Australian Association for Environmental Education, Inc., Brisbane. SPONS AGENCY Australian International Development Assistance Bureau.; Griffith Univ. Nathan, Brisbane (Australia). REPORT NO ISBN-0-9589087-2-9 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 519p.; Photographs in handout material may not copy adequately. AVAILABLE FROMAustralian Association for Environmental Education, Inc., Faculty of the Environmental Sciences, Griffith University, Nathan, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 4111 ($100 Australian, plus postage). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Conservation (Environment); *Ecology; *Economic Development; Elementary Secondary Education; "Environmental Education; Foreign Countries; *Futures (of Society); Higher Education; Preservice Teacher Education; Sustainable Development; *Teacher Workshops; Waste Disposal IDENTIFIERS Australia ABSTRACT This document is a curriculum for preservice teachers that attempts to illustrate how environmental education and development education are related and to provide practical assistance for teacher educators who would like to include these important fields in their programs. The project provides a focus for discussion of environmental and development education issues in teacher education in Australia. The particular audience for this project is preservice teacher -

September Cl Assic Movie Night 9 2Nd 1666

~ ~ Montpelier Montpelier consider the key aims of most private clients to be: The creation of wealth. The protection of wealth. The minimisation of taxation on wealth. Montpelier are strongly focused in providing clients with advice which enables them to meet these - Operating in over 10 countries with over 200 staff and over 19,000 clients, Montpelier are the ~ leaders in Private Wealth Management for expatriates. WWW.MONTPELIERGROUP.COM Setting Standards With a Global Presence London- Isle of Man-Bangkok- Kuala Lumpur-Hong Kong-Brussels-New York-Birmingham-Toky(X:) -- Montpelier (Thailand) Ltd, 75/68 Richmond Office Tower, 19th Fir, 75 Sukhumvit 26, Klongtoey, 8angko Tel: 02 661 5150 Fax: 02 661 5190 Email: [email protected] shrewsbury nternatio n a l s choo l reflection b7ossom shre w sbury international school, 1922 charoen krung road , w at prayakrai , bang kholame , b angkok 101 2 0 tel : (662) 675 1888 Fa x: (662) 675 3606 e - mail : enquiries @shrewsbur y.a c . th www. shre wsbur y . ac .th For more information about Accredited by: your child's future please contact the Admissions Office Tel: +66 (0) 2503 7222 Ext 1127, 1129, 1130 Fax: +66 (0) 2503 8286 Email: [email protected] HARROW Web: www.harrowschool.ac.th I TER ATIO AL SCHOOL One of our more interesting reciprocal clubs, the Explorer s Club serves as a meeting point and unifying force for explorers and scientists worlmvide. See NTE pages 36-37. ld London always had a problem with fi re. Following from the Chairman 5 the Norman Conquest in 1066, King Wi ll iam the OConqueror insisted that all fires in London should be from the new CEO 5 put out at night to reduce the risk of fire in houses with straw 'carpets' and thatched roofs. -

Beyond Gender?

Beyond gender? Abstract The purpose of this project is to look at the importance gender in the BBC show Doctor Who. This has been achieved by selecting ten focus characters for close analysis; five companions and five incarnations of the Doctor. The chosen characters are; Barbara Wright and the First Doctor, Tegan Jovanka and the Fifth Doctor, Ace and the Seventh Doctor, Rose Tyler and the Ninth Doctor, and finally Donna Noble and the Tenth Doctor. The analysis was based on a poststructuralist approach to the selected storylines of the show, in particular how the characters are influenced by gender roles and gender expectations. What this analysis showed was a tendency to stay close to the socially accepted norms of behaviour by males and females individually, although examples of pushing the boundary is also present. Based on the analysis, the discussion looked first at what values and personality traits which are shared by the selected companions, and secondly how the character of the Doctor has changed through the more than 50 years the show has existed. Interestingly enough, in both cases a tendency of a more mixed approach towards gender was uncovered, rather than an actual progress with the goal of achieving gender equality for the Time Lord and his companions. The overall purpose of this project is to answer; What is the importance of gender in relations to the characterisation of the Doctor and his female companions, in BBC’s Doctor Who, and how have these followed the progress of gender relations during the 54 years the show has been produced? 1 Table of content 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ -

Doctor with Confidence

BY COLIN BRAKE ISBN: 0-563-48652-X Contents Prologue 19 THREE 31 FOUR 43 FIVE 49 SIX 63 SEVEN 71 EIGHT 85 NINE 95 TEN 107 ELEVEN 121 TWELVE 131 THIRTEEN 141 FOURTEEN 153 FIFTEEN 165 Acknowledgements 173 About the Author 175 It was another perfect day in paradise. Sister Serenta could feel the warm golden sand between her toes as she walked barefoot along the beach, her moccasins in her hand. Saxik, the Fire Lord, was high in the sky, making the waves shimmer as they rolled gently on to the shore, sending bubbling sheets of sparkling water dancing over her feet. A gentle breeze cooled her brow, tempering the heat. Half a dozen cream-coloured sea birds were whirling in the sky. Serenta thought they looked as if they were playing some kind of game, chasing each other, zooming high and low and then floating without effort on the hot thermal currents. Sometimes, when she had been younger, Serenta had wondered how it would feel to fly like a bird, but now she was almost an adult she knew how silly that idea was. She glanced down at the wicker basket she was carrying. A few juicy red glasnoberries rolled around at the bottom, but only a handful. She knew she should have had a full basket by now. Laylora provides, she thought to herself with a smile, but we still have to do our bit. She started back into the forest to find the others. Her brother, Purin, and his friend Aerack were digging a new killing pit – the animal traps the Tribe of the Three Valleys used to catch wild pigs. -

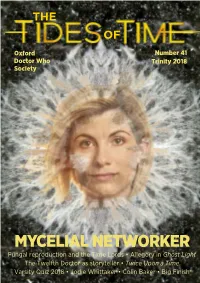

Mycelial Networker

THE OF Oxford Number 41 Doctor Who Trinity 2018 Society MYCELIAL NETWORKER Fungal reproduction and the Time Lords • Allegory in Ghost Light The Twelfth Doctor as storyteller • Twice Upon a Time Varsity Quiz 2018 • Jodie Whittaker • Colin Baker • Big Finish Number 41 Trinity Term 2018 Published by the OXFORD DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY [email protected] Contents 3 Editorial: ‘Change was possible. Change was here’ 4 Xenobiology Special: The Science of Whittaker J A 6 ‘Once Upon A Time, The End’: the Twelfth Doctor, Storyteller W S 11 Haiku for Smile W S 12 ‘Nobody here but us chickens’: The Empty Child B H 14 Running Towards the Future: new and old novelizations J W 20 The Doctor Falls No More: regeneration in Twice Upon a Time I B 23 Fiction: A Stone’s Throw, Part Three J S 29 2018 Varsity Quiz J A M K 36 The Space Museum W S 37 Looming Large S B R C 44 Paradise Lost: John Milton, unsuspected Doctor Who fan R B 46 The Bedford Boys: Bedford CharityCon 4-I I B 48 Mad Dogs and TARDIS Folk: the Doctor in Oxford J A 54 Mike Tucker: Bedford Charity Con 4-II I B 56 Big Who Listen: The Sirens of Time J S, R C, I B, A K, J A, M G, J P. M, P H 64 The Bedford Tales: Bedford CharityCon 4-III A K 67 Terror of the Zygons W S 68 Jodie Whittaker is the Doctor and the World is a Wonderful Place G H 69 The Mysterious Case of Gabriel Chase: Ghost Light A O’D Edited by James Ashworth and Matthew Kilburn Editorial address [email protected] Editorial assistance from Ian Bayley, Nancy Epton, Stephen Bell and William Shaw. -

1457900189981.Pdf

Table of Contents Cover Title Page Warhammer Map Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Epilogue About The Author Legal eBook license This is a dark age, a bloody age, an age of daemons and of sorcery. It is an age of battle and death, and of the world’s ending. Amidst all of the fire, flame and fury it is a time, too, of mighty heroes, of bold deeds and great courage. At the heart of the Old World sprawls the Empire, the largest and most powerful of the human realms. Known for its engineers, sorcerers, traders and soldiers, it isa land of great mountains, mighty rivers, dark forestsand vast cities. And from his throne in Altdorf reignsthe Emperor Karl Franz, sacred descendant of thefounder of these lands, Sigmar, and wielder of his magical warhammer. But these are far from civilised times. Across the length and breadth of the Old World, from the knightly palaces of Bretonnia to ice-bound Kislev in the far north, come rumblings of war. In the towering Worlds Edge Mountains, the orc tribes are gathering for another assault. Bandits and renegades harry the wild southern lands ofthe Border Princes. There are rumours of rat-things, the skaven, emerging from the sewers and swamps across the land. And from the northern wildernesses there is the ever-present threat of Chaos, of daemons and beastmen corrupted by the foul powers of the Dark Gods. -

Title Call No. Collection(Usage)

Title Call No. collection(Usage) Unexplained mysteries of the 20th century / AG243 .B63 1989 GEN 15 Dictionary of symbolism : cultural icons and the meanings behindAZ108 them .B5313/ 1994 GEN 14 A dictionary of symbols / AZ108 .C57 2002 c.2 GEN 52 The wisdom of Confucius, B128 .C7 L5 GEN 13 A short history of Confucian philosophy / B128 .C8 L58 1955 GEN 16 An introduction to Greek philosophy / B171 .L83 1992 GEN 16 Animal minds and human morals : the origins of the Western debateB187 / .M55 S67 1993 GEN 15 The philosophy of existentialism. B2430.S32 E5 1965 GEN 11 The will to power. B3313 .N5 1967 GEN 26 The last days of Socrates : Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo / B358 .T7 2003 GEN 23 Phaedo / B379 .A5 G34 1993 GEN 10 Symposium / B385 .A5 N44 1989 GEN 13 The Cambridge companion to Plato / B395 .C28 1992 GEN 15 An examination of Plato's doctrines. B395 .C7 v.1 GEN 16 Plato's theory of man; an introduction to the realistic philosophyB395 of culture, .W67 1964 GEN 13 Aristotle, from Natural science, Psychology, The Nicomachean ethics;B407 .W5 GEN 11 Sovereign virtue : Aristotle on the relation between happiness andB491 prosperity .H36 W45 / 1992GEN 13 The art of happiness; or, The teachings of Epicurus. B512 .S4 1933 GEN 11 Critical thinking and communication : the use of reason in argumentBC177 / .W35 1989 GEN 14 New knowledge in human values. BD232 .M34 GEN 17 Your sixth sense : activating your psychic potential / BF1031 .N35 1997 GEN 19 Memories, dreams, reflections. BF109 .J8 A33 GEN 24 Dark moon mysteries : wisdom, power, and magic