Mycelial Networker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File Under Licence

THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CREDITS LINE DEVELOPER: Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan WRITING: Darren Pearce and Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Nathaniel Torson EDITING: Dominic McDowall-Thomas COVER: Paul Bourne GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Paul Bourne CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Dominic McDowall-Thomas ART DIRECTOR: Jon Hodgson SPECIAL THANKS: Georgie Britton and the BBC Team for all their help. “My First Begins With An Unearthly Child” The First Doctor Sourcebook is published by Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd (UK reg. no.6036414). Find out more about us and our games at www.cubicle7.co.uk © Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2013 BBC, DOCTOR WHO (word marks, logos and devices), TARDIS, DALEKS, CYBERMAN and K-9 (wordmarks and devices) are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used Sample file under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. Doctor Who logo © BBC 2009. TARDIS image © BBC 1963. Dalek image © BBC/Terry Nation 1963.Cyberman image © BBC/Kit Pedler/Gerry Davis 1966. K-9 image © BBC/Bob Baker/Dave Martin 1977. Printed in the USA THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE 4 CHAPTER SEVEN 89 Introduction 5 The Chase 90 Playing in the First Doctor Era 6 The Time Meddler 96 The Tardis 12 Galaxy Four 100 CHAPER TWO 14 CHAPTER EIGHT 104 An Unearthly Child 15 The Myth Makers 105 The Daleks 20 The Dalek’s Master Plan 109 The Edge of Destruction 26 The Massacre 121 CHAPTER THREE 28 CHAPTER NINE 123 Marco Polo 29 The Ark 124 The Keys of Marinus 35 The Celestial Toymaker 128 The -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 Nationaltheatre.Org.Uk Find Us Online How to Book the Plays

This cover was created with the Lighting Department. Lighting is used to create moments of stage magic. The choices a Lighting Designer makes about how a set and actors are lit have a major impact on the mood and atmosphere of a scene. The National’s Lighting department deploys everything from flood or spotlight to complex automated lights, controlled via a lighting data network. Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 nationaltheatre.org.uk Find us online How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm See p29 for Sunday and holiday opening times Hedda Gabler LOVE Amadeus Playing from 5 December 6 December – 10 January Playing from 19 October Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm for the following week’s performances Day Tickets £15 / £18 tickets available in person on the day of the performance No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Peter Pan The Red Barn A Pacifist’s Guide to Playing from 16 November 6 October – 17 January the War on Cancer 14 October – 29 November Access symbols used in this brochure Captioned Touch Tour British Sign Language Relaxed Performance Audio-Described TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre NT Future is Partner for Sponsored by in partnership -

Galilee Flowers

GALILEE FLOWERS The Collected Essays of Israel Shamir Israel Adam Shamir GALILEE FLOWERS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 5 WHY I SUPPORT THE RETURN OF PALESTINIANS.................................................................... 6 PART ONE....................................................................................................................................... 8 THE STATE OF MIND ................................................................................................................. 8 OLIVES OF ABOUD.................................................................................................................... 21 THE GREEN RAIN OF YASSOUF................................................................................................ 23 ODE TO FARRIS ........................................................................................................................ 34 THE BATTLE FOR PALESTINE.................................................................................................. 39 THE CITY OF THE MOON ......................................................................................................... 42 JOSEPH REVISITED................................................................................................................... 46 CORNERSTONE OF VIOLENCE.................................................................................................. 50 THE BARON’S BRAID............................................................................................................... -

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

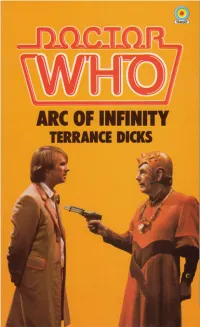

Doctor Returns to Gallifrey, He Learns That His Bio Data Extract Has Been Stolen from the Time Lords’ Master Computer Known As the Matrix

When the Doctor returns to Gallifrey, he learns that his bio data extract has been stolen from the Time Lords’ master computer known as the Matrix. The bio data extract is a detailed description of the Doctor’s molecular structure—and this information, in the wrong hands, could be exploited with disastrous effect. The Gallifreyan High Council believe that anti-matter will be infiltrated into the universe as a result of the theft. In order to render the information useless, they decide the Doctor must die... Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book Doctor Who — Time-Flight Doctor Who — Meglos Doctor Who — Four to Doomsday Doctor Who — Earthshock GB £ NET +001.35 ISBN 0-426-19342-3 UK: £1.35 *Australia: $3.95 *Recommended Price ,-7IA4C6-bjdecf-:k;k;L;N;p TV tie-in DOCTOR WHO ARC OF INFINITY Based on the BBC television serial by Johnny Byrne by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation TERRANCE DICKS A TARGET BOOK published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & WyndhamCompany 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB First published in Great Britain by W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd 1983 Novelisation copyright © Terrance Dicks 1983 Original script copyright © Johnny Byrne 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 19342 3 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Inside Outside in 2: an Outside in Extra!

INSIDE OUTSIDE IN 2: AN OUTSIDE IN EXTRA! Inside Outside In 2 as a compilation is ©2018 Robert Smith? All essays are ©2018 their respective authors. Outside In inside outside in 2 robert smith? (Originally published in the Nethersphere fanzine) Outside In Who The first two books cover Classic and New reviews, but with a twist. Well, technically a gimmickDoctor Who and storiesa twist. (including The gimmick Shada is). that, In the in second each volume, (recently there out is precisely one reviewer per story. So, in the first volume,Who there were 160 writers covering 160 Classic from ATB Publishing), that meant 125 writers Space/Timefor 125 New to Rainstories. Gods to How Time did Crash we toget Music to 125? of theWe Spherescounted. Notpretty to mentionmuch everything! all the televised So if it had stories a title of andcourse. a narrative, then it was included. Which meant everything from However, while a logistical triumph/headache/nightmareDoctor Who collection(delete asin appropriate), the gimmick is simply that: a way to anchor the collectionDoctor Who — making it, incidentally the most diverse professionally published existence — meaning that there are multiple styles. Much like itself, if you don’t like this week’s offering, somethingWho stories else will saying be along the shortly.same old things. So The twist though, is rather more delicious. The first volume was created as a hard.reaction Doctor to so Who many reviews of Classic the aim with that oneThe was Seeds to sayof Doom something different. Which, in a way, wasn’t that , like the weather, is endlessly discussable. -

A Graduate Project Submitted in Partial Satisfaction for the Degree of Master of Arts in Educational Psychology, Counseling and Guidance

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NJRTHRIIX:;E THE EFFECT OF LUNAR PERIODICI1Y ON HUMAN BEHAVIOR A graduate project submitted in partial satisfaction for the degree of Master of Arts in Educational Psychology, Counseling and Guidance by Janis Cash Graham May, 1984 The Gragua~roject of Janis Cash Graham is approved: Dr. Robert Docter Dr. Bernard NisenhOlZ Dr. Stan y Charnofsky ( ainnan) California State University, Northridge ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT . • • • • ~ • • . • . • ~ . • • • • . • • . • • . • v Chapter 1 INIRODUCTION 1 Purpose of the Project . • . 5 Limitations of the Project 6 Chapter 2 HISIDRY 8 Religion •.•...... 8 Folklore and Superstition. 14 Lycanthropy .......• 19 Chapter 3 IN SEARCH OF 'IHE ''LUNAR EFFECT'': PRESENT DAY INVESTIGATIONS • • • • 30 The Phases of the Moon 32 Case Studies • • . 34 Studies on Marine Life . 36 Biological Rhythms . 39 Medical Studies ..... 41 Studies of Human Behavior .. 44 The \IJork of Lieber and Sherin. 48 Chapter 4 MCDN AND MAN: 'IHEORIES . • . • 52 The Light of the moon. 52 The Geophysical Environment. 55 The Biological Tides Theory. 60 Other Theories of Man and the Moon 66 Chapter 5 APPLICATION AND St.M1ARY 71 Application to Research and Clinical Psychology. 71 Conceptual Application . 76 S'llii.llilary . • . • . • . 83 iii ~-' ' Page REFERENCES. 89 APPENDICES A DEFINITION OF TERMS 93 B ''A PERS01':W... NOTE'' • • 97 iv ABS'IRACT 'lliE EFFECT OF LUNAR PERIODICITY ON HUMAN BEHAVIOR by Janis Cash Graham Master of Arts in Educational Psychology Counseling and Guidance The belief in the power of the moon to influence life on our planet has existed from earliest recorded history, and plays an important role in the history of religion, folklore, and superstition. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Cat's Cradle Time's Crucible by Marc Platt Doctor Who: Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible by Marc Platt

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Cat's Cradle Time's Crucible by Marc Platt Doctor Who: Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible by Marc Platt. THIS STORY TAKES. PLACE BETWEEN THE NOVEL "TIMEWYRM: THE BIG FINISH AUDIO. RECOMMENDED. OFFICIAL VIRGIN 'NEW. ADVENTURE' PAPERBACK. (ISBN 0-426-20365-8) RELEASED IN FEBRUARY. The TARDIS is invaded. by an alien presence. and destroyed. The. Ace finds herself in a. bizarre deserted city. ruled by A leech-like. monster known as the. Lost voyagers drawn. forTH from Ancient. Gallifrey perform. obsessive rituals. in the ruins. strands of time are. tangled in a cat�s. cradle of dimensions. Only the Doctor can. challenge the rule. of the Process and. restore the stolen. But the Doctor was. destroyed long ago, before Time began. As popular as Ghost Light was, truncated into three episodes with its exposition on the cutting room floor, Marc Platt�s atmospheric television serial never quite worked for me. With this novel, however, the written word allows Platt the freedom to tell his story at a slower pace, making it easier for the reader to follow not only the broad strokes but also the intricate subtleties of his plot. For me, the brilliance of Cat�s Cradle: Time�s Crucible can be summed up in just one word: Gallifrey. This novel is the first story since The Deadly Assassin to really get to grips with. the rudiments of Time Lord civilisation, and the first story ever to flesh out the culture of this fascinating race in any sort of satisfactory fashion. -

Oxford Doctor Who Society

OXFORD DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY Michaelmas Term 2019 EPISODE SCREENINGS! QUIZZES! RECONSTRUCTIONS! FOOD! TIMEY-WIMEY STUFF! WEEK Spearhead from Space Thursday 17th October, 8pm, Seminar Room, Corpus Christi College To kick off the academic year we’re watching the first episode with the Third Doctor, in which he fights a plastic-controlling alien which will no 1 doubt be familiar to most Freshers that grew up on the new series. For a bit of context, the Doctor has been sent to and trapped on Earth by his own kind as a punishment. Newly regenerated, he is found by UNIT during a somewhat suspicious meteorite shower. Along with Liz Shaw and the Brigadier, the Doctor must work to thwart this would-be colonising alien. Quiz of Rassilon Sunday 20th October, 7pm, Sebright Arms, Coate St., London This monthly quiz, based in a London pub, is usually centred around a few particular Doctor Who episodes, which WhoSoc members marathon during the day on Sunday (or occasionally the day before too if there’s lots to cover) before travelling up to London with life-size Eccleston in tow to battle it out in the quiz against other Doctor Who fans from across the country. This time around, the stories featured will be those from Series 9 of so-called “Nu-Who” and the epic Colin Baker saga The Trial of a Time Lord, with a round specifically focussing on Peri, one of his companions. All are welcome to join us for the quiz up in London, or just pop along for the marathon (we understand that many of you freshers might have a matriculation to suffer through!). -

Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SCORE ADDITIONAL CUES FOR 4-PART VERSION 01 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors) 0.36 34 End of Episode 1 (Sarah Falls) 0.11 02 New Console 0.24 35 End of Episode 2 (Cybermen III variation) 0.13 03 The Eye of Orion 0.57 36 End of Episode 3 (Nothing to Fear) 0.09 04 Cosmic Angst 1.18 05 Melting Icebergs 0.40 37 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue (Premix) 1.22 06 Great Balls of Fire 1.02 07 My Other Selves 0.38 08 No Coordinates 0.26 09 Bus Stop 0.23 10 No Where, No Time 0.31 11 Dalek Alley and The Death Zone 3.00 12 Hand in the Wall 0.21 13 Who Are You? 1.04 14 The Dark Tower / My Best Enemy 1.24 15 The Game of Rassilon 0.18 16 Cybermen I 0.22 17 Below 0.29 18 Cybermen II 0.58 19 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen III 0.34 20 Raston Robot 0.24 21 Not the Mind Probe 0.10 22 Where There’s a Wind, There’s a Way 0.43 23 Cybermen vs Raston Robot 2.02 24 Above and Between 1.41 25 As Easy as Pi 0.23 26 Phantoms 1.41 27 The Tomb of Rassilon 0.24 28 Killing You Once Was Never Enough 0.39 29 Oh, Borusa 1.21 30 Mindlock 1.12 31 Immortality 1.18 32 Doctor Who Closing Theme - The Five Doctors Edit 1.19 33 Death Zone Atmosphere 3.51 SPECIAL EDITION SCORE 56 The Game of Rassilon (Special Edition) 0.17 57 Cybermen I (Special Edition) 0.22 38 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors Special Edition) 0.35 58 Below (Special Edition) 0.43 39 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue 1.17 59 Cybermen II (Special Edition) 1.12 40 The Eye of Orion / Cosmic Angst (Special Edition) 2.22 60 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen