Acoustics Towards Italian Opera Houses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARLA DELFRATE Direttore D’Orchestra

CARLA DELFRATE direttore d’orchestra curriculum Nata a Parma si è diplomata in oboe e direzione d’orchestra al Conservatorio “A. Boito” della sua città sotto la guida dei maestri Piero Guarino e Daniele Gatti. Nel 1987 ha Fondato l’orchestra da camera “Il Divertimento Musicale” con la quale ha diretto numerosi concerti anche con strumenti solisti in diverse città italiane. Nel 1992 è stata nominata direttore stabile dell’Orchestra Femminile Europea esibendosi in sedi prestigiose quali i Conservatori di Milano e Torino e partecipando a concerti televisivi sulle reti Rai e Mediaset. Dopo aver lavorato diversi anni come maestro sostituto al Teatro Regio di Parma, ha debuttato nella direzione dell’opera lirica dirigendo diversi titoli : OrFeo ed Euridice di Gluck al Teatro di Documenti di Roma con la regia di Luciano Damiani; Il barbiere di Siviglia di Paisiello al WexFord Festival Opera; Andrea Chénier di Giordano, Tosca di Puccini, Lucia di Lammermoor di Donizetti, La Forza del destino, Attila, Un ballo in maschera di Verdi al Teatro Magnani di Fidenza; Luisa Miller e Rigoletto al Teatro Verdi di Busseto; L’enfant prodigue di Debussy e Cavalleria Rusticana di Mascagni per l’inaugurazione della stagione lirica 2013 del Teatro delle Muse di Ancona; Così Fan tutte di Mozart nei teatri Coccia di Novara, Alighieri di Ravenna, Municipale di Piacenza con la regia di Giorgio Ferrara; Le nozze di Figaro di Mozart al Teatro Sociale di Mantova, Lucrezia Borgia al Teatro Sociale di Bergamo nell’ambito del Festival Donizetti Opera 2019. Dal 1998 al 2000 è stata assistente musicale della Fondazione “Arturo Toscanini” di Parma, sede dell’omonima orchestra, con la quale ha diretto numerosissimi programmi sinfonici e lirici tra cui due edizioni del Concorso Voci Verdiane di Busseto. -

Il Barbiere Di Siviglia Soci Fondatori

TEATRO MUNICIPALE PIACENZA STAGIONE 2020 GIOACHINO ROSSINI IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA SOCI FONDATORI COMUNE DI PIACENZA CONSIGLIO DIRETTIVO Presidente Patrizia Barbieri Consiglieri Giuseppina Campolonghi Barbara Zanardi COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI Davide Cetti Annamaria Marenghi Umberto Tosi con il contributo di MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI Direttore e Direttore Artistico Cristina Ferrari 20 DICEMBRE 2020 ore 15.30 GIOACHINO ROSSINI IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA Melodramma buffo in due atti di Cesare Sterbini dalla commedia omonima di Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (Edizione Edwin F. Kalmus) Conte d’Almaviva MANUEL AMATI Don Bartolo MARCO FILIPPO ROMANO Rosina GIUSEPPINA BRIDELLI Figaro ROBERTO DE CANDIA Don Basilio MATTIA DENTI Berta STEFANIA FERRARI Fiorello FRANCESCO CASCIONE Ambrogio MICHELE ZACCARIA Un ufficiale SIMONE TANSINI direttore NIKOLAS NÄGELE regia BEPPE DE TOMASI ripresa da RENATO BONAJUTO scene POPPI RANCHETTI costumi ARTEMIO CABASSI luci MICHELE CREMONA ORCHESTRA DELL’EMILIA-ROMAGNA ARTURO TOSCANINI CORO DEL TEATRO MUNICIPALE DI PIACENZA CORRADO CASATI maestro del coro coproduzione Teatro Regio di Parma, Teatro Municipale di Piacenza Direttore di scena Ermelinda Suella Maestro di sala e clavicembalo Gianluca Ascheri Maestri collaboratori di palcoscenico Patrizia Bernelich, Ko Gaboon Maestro alle luci Paolo Burzoni Responsabile tecnico Michele Cremona Scene Laboratori di scenotecnica del Teatro Regio di Parma Attrezzeria Teatro Regio di Parma, Rancati Milano Costumi e parrucche Arte Scenica, Reggio Emilia Calzature -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

Stefano Trespidi

Stefano Trespidi Curriculum Vitae A) DATI PERSONALI DATA E LUOGO DI NASCITA 23 maggio 1970 Verona B) COMPETENZE LINGUISTICHE Oral Written ITALIAN Excellent Excellent ENGLISH Good Good FRENCH Good Medium SPANISH Good Medium GERMAN Basic Not Sufficient ARABIC First course No C) STUDI Laurea in Giurisprudenza presso l’ Università degli Studi di Trento 110/110 Laurea in Scienza delle Comunicazioni presso l’ Università degli Studi di Verona 108/110 Laureando in Economia Aziendale presso l’ Università degli Studi di Verona MASTER IN Criminal Justice al John Jay College, New York VISITING SCHOLAR alla Universitad Interamericana de Puertorico, Aguadilla VISITING SCHOLAR al Trinity College, Dublin VISITING SCHOLAR alla Cujas Library, Paris D) Principali esperienze lavorative al di fuori del teatro d’opera 1996 – 1999 Pratica legale presso Studio Turri Via A. Sciesa 9 Verona. +39.0458001929 2001 – 2003 Direttore delle Risorse Umane presso C.S.A. central security agency Via Ca’ di Cozzi 41 Verona. +39.0458302572 E) ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE NEL CAMPO DELL’OPERA LIRICA E1) 2005-2017 Responsabile Settore Regia Fondazione Arena di Verona E2) REGISTA TRISTAN UND ISOLDE (R.Wagner) Filarmonico di Verona 2004 TRAVIATA (G. Verdi) Filarmonico di Verona 2005 PARLATORE ETERNO (A. Ponchielli) Filarmonico di Verona 2006 NOZZE DI FIGARO (W.A. Mozart) Teatro de Amarante 2007 GALA DOMINGO (G.Verdi; G. Bizet) Arena di Verona 2009 AIDA (G.Verdi) Tokyo International Forum 2010 MACBETH (G.Verdi) Filarmonico di Verona 2012 GALA VERDI (G. Verdi) Arena di Verona -

Download the Things to Do in Palermo PDF

Things to do in Palermo Palermo is the regional capital of Sicily, which is the largest and most heavily populated (about 5,000,000) island in the Mediterranean. The area has been under numerous dominators over the centuries, including Roman, Carthaginian, Byzantine, Greek, Arab, Norman, Swabian and Spanish masters. Due to this past and to the cultural exchange that for millennia has taken place in the area, the city is still an exotic mixture of many cultures. Many of the monuments still exist and are giving the city an unique appearance. The city of Palermo, including the province of Palermo, has around 1,300,000 inhabitants and has about 200 Km of coastline. The old town of Palermo is one of the largest in Europe, full of references to the past. Palermo reflects the diverse history of the region in that the city contains many masterpieces from different periods, including romanesche, gothic, renaissance and baroque architecture as well as examples of modern art. The city also hosts it's rich vegetation of palm trees, prickly pears, bananas, lemon trees and so on. The abundance of exotic species was also noticed by the world- famous German writer Goethe who in April 1787 visited the newly opened botanical gardens, describing them as "the most beautiful place on earth". Below, we would like to provide you with some useful information and advices about things to do and see during your stay in Palermo. We are happy to provide any further information you might require. Best regards The Organizing Secretary of Euroma2014 Conference MUSEUM The Gallery of Modern Art Sant'Anna or GAM is a modern art museum located in Via Sant'Anna, in Kalsa district of the historical centre of Palermo. -

Stephen Medcalf Stage Director

Stephen Medcalf Stage Director Stephen Medcalf’s current and future engagements include UN BALLO IN MASCHERA and DIE WALKÜRE Grange Park Opera, LEONORE and IDOMENEO Buxton Festival, HERCULANUM Wexford Festival Opera, MANON LESCAUT Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía in Valencia and Asociación Bilbaina de amigos de la Ópera in Bilbao, FALSTAFF Accademia della Scala on tour to Royal Opera House Muscat in Oman and AIDA and ARIODANTE Landestheater Niederbayern. Recent new productions include NORMA Teatro Lirico Cagliari, AIDA The Royal Albert Hall, A VILLAGE ROMEO AND JULIET and Foroni’s CRISTINA REGINA DI SVEZIA Wexford Festival, FALSTAFF Teatro Farnese, Parma, ALBERT HERRING, ARIADNE AUF NAXOS and DEATH IN VENICE Salzburger Landestheater, LA FINTA GIARDINIERA Landestheater Niederbayern, EUGENE ONEGIN, LA BOHEME FANCIULLA DEL WEST and CAPRICCIO Grange Park Opera, Bellini’s IL PIRATA and Menotti’s THE SAINT OF BLEECKER STREET Opéra Municipal Marseille, LUCREZIA BORGIA, LUISA MILLER, MARIA DI ROHAN, Gluck’s ORFEO ED EURYDICE and Mascagni’s IRIS Buxton Festival, CARMEN and AIDA Teatro Lirico di Cagliari, CARMEN Teatro Nacional de São Carlos, Cesti’s LE DISGRAZIE D’AMORE Teatro di Pisa and a revival of his DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía in Valencia. Career highlights include PIKOVAYA DAMA Teatro alla Scala, LE NOZZE DI FIGARO Glyndebourne Opera House (televised and released on video/DVD), MANON LESCAUT and DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE (released on DVD) Teatro Regio di Parma, and DIE ENTFUHRUNG AUS DEM SERAIL for Teatro delle Muse, Ancona, which was subsequently seen at the Teatro Massimo, Palermo, Teatro Lirico di Cagliari and the Theatre Festival of Thessaloniki. -

Eric Greene Baritone

Eric Greene Baritone Eric Greene’s current and future engagements include ESCAMILLO Carmen Liceu Barcelona, WOTAN Das Rheingold Birmingham Opera Company, Rigoletto (title role) Opera North, and his main-stage Royal Opera House, Covent Garden debut in a new production of Rigoletto. Most recent engagements include RICHARD NIXON Nixon in China Scottish Opera, PORGY Porgy and Bess English National Opera and Theater an der Wien, AMONASRO Aida Opera North, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchcestra conducted by Sir Simon Rattle, the leading role of OBERON Hans Gefors‘ Der Park Malmö Opera, TRINITY MOSES Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny Salzburger Landestheater, BILL Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny Teatro dell’opera di Roma, HENRY DAVIS Weill’s Street Scene Teatro Real, Mozart Requiem Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the leading role of JANITOR Tansy Davies’ Between Worlds (world premiere) English National Opera at the Barbican, DONNER Das Rheingold and GUNTHER Götterdämmerung Teatro Massimo in Palermo, CROWN Porgy and Bess Lyric Opera of Chicago, Atlanta Opera, Sydney Symphony and Spoleto Festival, Porgy and Bess Suite Teatro Nacional de São Carlos Lisbon, The Knife of Dawn (world premiere) Roundhouse, IVAN KHOVANSKY Khovanshschina, AENEAS Dido and Aeneas and SEGISMUNDO Jonathan Dove’s Life is a Dream (world premiere) Birmingham Opera, BILLY BIGELOW Carousel Opera North at the Barbican, GUNTHER Götterdämmerung Opera North, ESCAMILLO Carmen Portland Opera, QUEEQUEG Moby Dick Washington National Opera, MELOT Tristan und Isolde Casals Festival with the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra. Other performances have included ESCAMILLO Carmen Virginia Opera, ROBERT GARNER in Danielpour’s Margaret Garner (world premiere) Michigan Opera Theater, Opera Company of Philadelphia and Opera Carolina, ESCAMILLO La Tragédie de Carmen Augusta Opera, SOLOIST Kirke Mechem’s Songs to the Slave and Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Dona nobis pacem Bel Canto Chorus Milwaukee, SOLOIST Richard Danielpour’s Pastime Northwestern University. -

Emilia Romagna Il Tavolino Degli Hipster

EMILIA ROMAGNA IL TAVOLINO DEGLI HIPSTER. ottobre 2010 freetimeguide DIR. RESPONSABILE: Come lavorano i cacciatori di nuove tendenze di oggi, Nicola Brillo i cool hunter? COORDINAMENTO DI EDIZIONE: Giorgio Govi ([email protected]) Mariagiovanna Bonesso Un paio di anni fa, ad una delle riunioni dei cool hunter ART DIRECTION: di FFWDblog.it, il ritratto del cool hunter degli anni No- Daniele Vian ([email protected]) IMPAGINAZIONE & GRAFICA: vanta ci aveva dato un globetrotter con zaino in spalla 4 Diana Lazzaroni, Riki Kontogianni, e macchina fotografica in mano. L’identikit di quello del Speciale Giorgia Vellandi nuovo millennio aveva tratteggiato un esperto surfer An Up and Down Motion HANNO COLLABORATO: Elisabetta Pasqualetti, Roberta Ambrosini, della rete, consumatore onnivoro di riviste, notizie Federica Iacobelli, Valentina Marchesi, virtuali e segnali deboli da captare attraverso i più Elena Ferrarese, Lorenzo Tiezzi, improbabili post di blog e siti specializzati. 16 Gabriele Vattolo, Paolo Braghetto. Live music / concerti gratis COPERTINA: Daniele Vian Due anni nel mondo delle tendenze sono però equiva- STAMPA: Chinchio Industria lenti a secoli (chi aveva l'iPhone nel giugno del 2008?) Grafica - Rubano (PD) 22 e molti dei cool hunter di allora sono finiti a condurre Bologna attività con più certezze come la lettura dei tarocchi nei canali dopo900 di Sky. Quelli che sono rimasti sono tornati a monitorare le strade e i locali dove si 32 AREA COMMERCIALE costruisce la nightlife, perché la necessità di toccare Modena & PUBBLICITA’: con mano e vedere con i propri occhi ha sopravanzato [email protected] - [email protected] gli stimoli virtuali. 36 testata reg. -

Anna Irene Del Monaco

The Shri Radha-Radhanath Temple of Understanding in the formerly Indian township of Chatsworth, Durban. Photo: Anna Irene Del Monaco. 120 Theaters and cities. Flânerie between global north-south metropolis on the traces of migrant architectural models ANNA IRENE DEL MONACO, FRANCESCO MENEGATTI Sapienza Università di Roma; Politecnico di Milano [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: Theaters around the world are linked by architectural features besides programs and music. (AIDM: A.I. Del Monaco; FM: Francesco Menegatti) The conversation begins by commenting on the concert by Martha Argerich and Daniel Baremboim with the Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala held in Piazza Duomo on May 12, 2016 in Milan. The Concerto in Sol by Ravel is scheduled in the program. The hybrid Neoclassicism of theaters in the modern city between the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries: the Teatro alla Scala in Milan - the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires - the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow - the Sans Souci Theater in Kolkata - the Teatro Massimo in Palermo. AIDM: The Argerich-Baremboim concert and the La Scala Philharmonic Orchestra set up in Piazza Duomo en plein air with 40,000 spectators seems to have been a great success. The two ultra-seventies artists, born in Argentina, seemed at their ease ... two classical music stars within the scenography of Milan urban scenes ... the Cathedral on the right of the stage and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in front of the orchestra. This shows how the urban architecture of Italian historical cities, even when it is composed of architectures from different eras, is able to represent a perfect stage, both formal and informal, and the music is always done on the street, en plein air, as we learn, among other things, from the quintet of Luigi Boccherini of 1780 Night music on the streets of Madrid. -

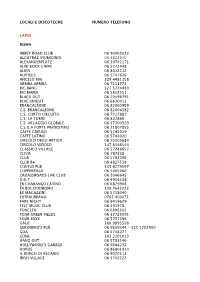

Database Locali Live

LOCALI E DISCOTECHE NUMERO TELEFONO LAZIO ROMA ABBEY ROAD CLUB 06 90405022 ALCATRAZ (FIUMICINO) 06 4823650 ALEXANDERPLATZ 06 39742171 ALIBI ROCK CAFFE 06 5743448 ALIEN 06 8412212 ALPHEUS 06 5747826 ANGELO MAI 329 4481358 ARRIBA ARRIBA 06 7213772 BIG BANG 327 5724480 BIG MAMA 06 5812551 BLACK OUT 06 70496791 BLUE KNIGHT 06 6630011 BRANCALEONE 06 82000959 C.S. BRANCALEONE 06 82004382 C.S. CORTO CIRCUITO 06 7217682 C.S. LA TORRE 06 822869 C.S. VILLAGGIO GLOBALE 06 57300329 C.S.O.A FORTE PRENESTINO 06 21807855 CAFFE CARUSO 06 5745019 CAFFE LATINO 06 5744020 CIRCOLO DEGLI ARTISTI 06 70305684 CIRCOLO VIZIOSO 347 8146544 CLASSICO VILLAGE 06 57288857 CLIVIS 06 787838 CLUB 06 5782390 CLUB 84 06 4827538 COETUS PUB 335 6279097 COPPERFIELD 0 6 5 4 0 5 0 6 0 CROASSROADS LIVE CLUB 06 3046645 D.D.T. 06 4958338 ER CHARANGO LATINO 06 6879908 EX BOCCIODROMO 339 7642222 EX MAGAZZINI 06 5758040 EXTRAURBANO 0765 400071 FARE NIGHT 06 9419629 FELT MUSIC CLUB 06 491978 FONCLEA 06 6896302 FOUR GREEN FIELDS 06 37725091 FOUR XXXX 06 5757296 GALU' 388 9995598 GERONIMO'S PUB 06 9309344 - 333 3202900 GOA 06 5748277 GONE 393 2101013 HANG OUT 06 5783146 HOLLYWOOD’S GARAGE 06 9344232 HORUS 06 86801410 IL BORGO DI ASCANIO 06 9070113 IRISH VILLAGE 06 5742222 JAILBREAK 06 4063155 L.O.A ACROBAX PROJECT 340 2501155 LANIFICIO 159 06 41734052 - 329 4492185 LE IENE 06 5431878 LINUX CLUB 06 57250551 LO SPAZIO EBBRO 340 5497763 LOCANDA ATLANTIDE 06 44704540 MAHALIA 06 78850225 - 06 7883898 MICCA CLUB 06 87440079 - 349 5532135 MOON CLUB 06 41731307 NEW MISSISIPI JAZZ CLUB 06 68806348 -

E Delle Colline Moreniche

Dipende GIORNALEe delle del Colline GARDA Moreniche MENSILE DI CULTURA MUSICA TEATRO ARTE POESIA ENOGASTRONOMIA OPINIONI INTORNO AL GARDA DA BRESCIA A TRENTO DA VERONA A MANTOVA DA MILANO PASSANDO PER CREMONA FINO A VENEZIA GIORNALE DEL GARDA mensile edito da A.C.M. INDIPENDENTEMENTE via delle rive,1 Desenzano (BS) Tel. 030.9991662 E-mail: [email protected] MARZO 2010 Reg.Stampa Trib.diBrescia n.8/1993del29/03/1993 Poste Italiane S.p.A. - Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale - D.L.353/2003 (conv.L.27/02/2004 n.46) art.1, DCB Brescia - Abbonamento annuale 20 Euro n. 187 anno XVII copia omaggio www.dipende.it www.giornaledelgarda.com www.giornaledelgarda.net Tutti gli appuntamenti del Garda Editoriale 03 Servizi turistici del Garda 04 Promozione Garda unico 05 No al traforo delle Torricelle 06 Sostenibilità: architettura verde 07 Addio difensore civico? 08 CDO Brescia 09 Attualità 10 Dipende Voci del Garda 11 Festa della donna 12-13 Cultura 14 Enogastronomia 15 Strada dei Vini del Garda 16 Come se fa... El salàm 17 Il tortellino di Valeggio 17 Il biscotto di Pozzolengo 18 108^ fiera di San Giuseppe 19 Nautincontro 2010 20 Sirmione 2: il porto 21 Spettacoli 22 Eventi nel Garda bresciano 23-25 Eventi in Val Sabbia 26 Eventi di Mantova e provincia 27 Eventi del Garda veronese 28 Peschiera del Garda 29 Eventi del Garda Trentino 30 Incanto d'oriente 31 Gallerie intorno al Garda 31 Mostre 32-33 Musica: Charlie Cinelli 34 Musica live 35 Musica classica 36 Sport 37-38 foto R. Visconti Dipende 1 Dipende 2 REGISTRO OPERATORI della CO- editoriale MUNICAZIONE Iscrizione N.5687 Dipende a Monaco di Baviera per la promozione del Garda Unico associato alla Unione Stampa Periodica Italiana SINTONIZZATI Editore: Associazione Culturale Multimediale Indipendentemente ALL’INTERNAZIONALITÀ Direttore Responsabile: Giuseppe Rocca Una delegazione delle nostre di direzionalità espressiva della testata, che gira Direttore Editoriale: e si raccorda ad ampio respiro con un territorio in Raffaella Visconti Curuz testate ha affiancato i costante e progressiva evoluzione programmatica. -

Yes, Virginia, Another Ballo Tragico: the National Library of Portugal’S Ballet D’Action Libretti from the First Half of the Nineteenth Century

YES, VIRGINIA, ANOTHER BALLO TRAGICO: THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF PORTUGAL’S BALLET D’ACTION LIBRETTI FROM THE FIRST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro, M.F.A., M.A., B.F.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Karen Eliot, Adviser Nena Couch Susan Petry Angelika Gerbes Copyright by Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro 2015 ABSTRACT The Real Theatro de São Carlos de Lisboa employed Italian choreographers from its inauguration in 1793 to the middle of the nineteenth century. Many libretti for the ballets produced for the S. Carlos Theater have survived and are now housed in the National Library of Portugal. This dissertation focuses on the narratives of the libretti in this collection, and their importance as documentation of ballets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, from the inauguration of the S. Carlos Theater in 1793 to 1850. This period of dance history, which has not received much attention by dance scholars, links the earlier baroque dance era of the eighteenth century with the style of ballet of the 1830s to the 1850s. Portugal had been associated with Italian art and artists since the beginning of the eighteenth century. This artistic relationship continued through the final decades of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century. The majority of the choreographers working in Lisbon were Italian, and the works they created for the S. Carlos Theater followed the Italian style of ballet d’action.