Three Essays on Social Assistance in Canada: a Multidisciplinary Focus on Ontario Singles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C. Dewar Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 53, Number/numéro 1, Winter/hiver 2019, pp. 178-196 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719555 Access provided by Mount Saint Vincent University (19 Mar 2019 13:29 GMT) Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d’études canadiennes Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent KENNETH C. DEWAR Abstract: This article argues that the lines separating different modes of thought on the centre-left of the political spectrum—liberalism, social democracy, and socialism, broadly speaking—are permeable, and that they share many features in common. The example of Tom Kent illustrates the argument. A leading adviser to Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Kent argued for expanding social security in a way that had a number of affinities with social democracy. In his paper for the Study Conference on National Problems in 1960, where he set out his philosophy of social security, and in his actions as an adviser to the Pearson government, he supported social assis- tance, universal contributory pensions, and national, comprehensive medical insurance. In close asso- ciation with his philosophy, he also believed that political parties were instruments of policy-making. Keywords: political ideas, Canada, twentieth century, liberalism, social democracy Résumé : Cet article soutient que les lignes séparant les différents modes de pensée du centre gauche de l’éventail politique — libéralisme, social-démocratie et socialisme, généralement parlant — sont perméables et qu’ils partagent de nombreuses caractéristiques. -

1965-66-Rapport-Annuel.Pdf

RAPPORT ANNUEL DU CONSEIL DES ARTS DU CANADA 1965-1966 CONSEIL DES ARTS DU CANADA Neuvième rapport annuel 19651966 L'honorable Judy LaMarsh, Secrétaire d'Etat du Canada, Ottawa, Canada. Madame, J'ai l'honneur de vous transmettre, pour présentation au Parlement, le rapport du Conseil des Arts du Canada pour l'exercice financier qui s'est terminé le 31 mars 1966, conformément B l'article 23 de la Loi sur le Conseil des Arts du Canada (5-6 Elisabeth II, 1957, chapitre 3). Veuillez agréer, Madame, l'expression de mes sentiments distingués. Le president, i”-yZ, Le 30 juin 1966. Table des matières page 1 Avant-propos 4 Première partie: Les arts 4 Le grand jeu 6 Sondages 8 Le Programme de développement des arts de la scène 11 Séminaire ‘66 et considérations diverses 14 L’interpénétration des arts 17 Nouveaux mentors 19 Deuxième partie: Les humanités et les sciences sociales 20 Bourses de doctorat 21 Bourses de travail libre 21 Subventions à la recherche 23 Collections de recherche des bibliothèques 24 Aide à l’édition et aux conférences 25 Troisième partie: Programmes spéciaux 25 Bourses en génie, en médecine et en sciences 2.5 Echanges avec les pays francophones 26 Prix Molson 27 Quatrième partie: Le programme de construction 28 Cinquième partie: La Commission canadienne pour Wnesco 28 Activités durant l’année 29 Publications 30 Statuts et composition 30 Le Canada et 1’Unesco 32 Sixième partie: Finances 32 Placements 32 Caisse de dotation 34 Caisse des subventions de capital aux universités 3.5 Caisse spéciale 35 Etat des placements: revenus, -

The Role of House Leaders in the Canadian House of Commons Author(S): Paul G

Société québécoise de science politique The Role of House Leaders in the Canadian House of Commons Author(s): Paul G. Thomas Source: Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Mar., 1982), pp. 125-144 Published by: Canadian Political Science Association and the Société québécoise de science politique Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3230296 Accessed: 02/09/2009 08:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cpsa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Canadian Political Science Association and Société québécoise de science politique are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique. -

SUPERIOR COURT (Class Action Division) CANADA PROVINCE of QUÉBEC DISTRICT of MONTREAL N° : 500�06�000076�980 500�06�000070�983

SUPERIOR COURT (Class Action Division) CANADA PROVINCE OF QUÉBEC DISTRICT OF MONTREAL N° : 500-06-000076-980 500-06-000070-983 DATE : June 9, 2015 ________________________________________________________________ PRESIDING: THE HONORABLE BRIAN RIORDAN, J.S.C. ________________________________________________________________ No 500-06-000070-983 CÉCILIA LÉTOURNEAU Plaintiff v. JTI-MACDONALD CORP. (" JTM ") and IMPERIAL TOBACCO CANADA LIMITED. (" ITL ") and ROTHMANS, BENSON & HEDGES INC. (" RBH ") Defendants (collectively: the " Companies ") AND NO 500-06-000076-980 CONSEIL QUÉBÉCOIS SUR LE TABAC ET LA SANTÉ and JEAN-YVES BLAIS Plaintiffs v. JTI-MACDONALD CORP. and IMPERIAL TOBACCO CANADA LIMITED. and ROTHMANS, BENSON & HEDGES INC. Defendants JUDGMENT CORRECTING CLERICAL ERRORS JR1353 IN PARAGRAPHS 1114 and 1209 through 1213 500-06-000076-980 PAGE: 2 500-06-000070-983 INDEX SECTION PAGE RÉSUMÉ DU JUGEMENT // SUMMARY OF JUDGMENT 8 I. THE ACTIONS 11 A. The Parties and the Common Questions 11 B. The alleged bases of liability 15 C. The Companies' view of the key issues 18 II. IMPERIAL TOBACCO CANADA LTD. 19 A. Did ITL manufacture and sell a product that was dangerous and harmful to the health of consumers? 19 B. Did ITL know, or was it presumed to know, of the risks and dangers associated with the use of its products? 22 B.1 The Blais File 22 B.1.a As of what date did ITL know? 22 B.1.b As of what date did the public know? 28 B.1.b.1 The Experts' opinions: the Diseases and Dependence 28 B.1.b.2 The effect of the Warnings: the Diseases and Dependence 34 B.2 The Létourneau File 38 B.2.a As of what date did ITL know? 38 B.2.b As of what date did the public know? 39 C. -

Identification of Material

Identification of Material The following has been provided as reference material only. The information provides background information regarding the facilities in question as well as additional information on policies and requirements of PWGSC. The Bidder Information Package contains the following: 1. Active Space with Occupancy Information 2. Asset Management Plan Procedure 3. Building Management Plan Call Letter 4. Building Heritage Information 5. Commercial Lettings 6. Energy Consumption 7. Historical Financials 8. Policies not available to public 9. Service Call Reports Report Title: Listing of Buildings and their Occupants Selection Criteria: All active assets in the Facilities Inventory System for windows (WinFIS) as of the run date : September 6, 2012. The potential annual rent only represents an estimated revenue based on 100% occupancy and agreements being in place. For actual revenues, a report from OIS can be generated for this purpose. The total rentable m² is based on current occupancy regardless of the accommodation status (either occupied by federal client, by a third party client or is vacant). Includes assets in the operational and commissioned stages. Excludes land, livable and parking areas. RPU Name = DND Data Ctr. Ottawa Bldg. #16 - Tunney's Pasture - 40000527; Health Protection Building #7 - Tunney's - 40001098 Ministerial Name = Third Party Notes: Only usable space categories as per the Framework for Office Accommodation and Accommodation Services are selected. The Office area refers to the space categories: A- Office, B- Retail and E- Computer. The percentage of occupancy represents the total rentable area occupied by the client in relation to the total rentable area of the building. Sort: RPU Name - group by, page break Occupant Name Report: Regional\Inventory\Asset Listing\Buildings & Occupants | d_b-05_bldg_occ (n22a) Page 1 of 2 Listing of Buildings and their Occupants As of September 6, 2012 National Capital Area Rentable Area (m²) Related Total Activity Current AFD Cost Resp. -

Shadow Cabinet Organization in Canada

SHADOW CABINET ORGANIZATION IN CANADA 1963-78 by KAREN ORT B.A., (Honours), Queen's University at Kingston, 1977 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1978 © Karen Ort, 1978 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date September 5» 1978 i i ABSTRACT The .study, focuses on shadow cabinet organization, the practice; of appointing members to shadow the activities of cabinet ministers by Opposition parties. This practice is analyzed in Canada between 1963 and 1978, a period of continual Progressive Conservative Opposition. The under• lying question is whether shadow cabinet organization has become more or less institutionalized during the period. In the introduction Samuel Huntington's four tests of institutionalization are outlined. They were used in assessing Canadian shadow cabinet institutionalization. To operationalize the tests for this study it proved use• ful to analyze the institution of the Canadian cabinet system along these dimensions. -

How Canada's History Hall Has Evolved Over 50 Years

Wallace-Casey, C. (2018) ‘Constructing patriotism: How Canada’s History Hall has evolved over 50 years’. History Education Research Journal, 15 (2): 292–307. DOI https://doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.15.2.10 Constructing patriotism: How Canada’s History Hall has evolved over 50 years Cynthia Wallace-Casey* – University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract In this article, I illustrate how the national narrative in Canada’s Museum of History has evolved over 50 years. Located in the national capital of Ottawa, the new Canada’s History Hall presents a concise overview of a nation, stretching from time immemorial to the present. It was opened on 1 July 2017 as a signature exhibition in celebration of Canada’s sesquicentennial. It also represents a fourth manifestation of a national museum narrative for Canada. From humble beginnings in 1967 (when Canada celebrated its centennial), the narrative has changed substantially in response to national policies and societal values. Adopting a critical discourse analysis methodology, and drawing from archival evidence, I analyse how this national narrative has evolved. Canada’s History Hall presents Canadian students with a concise national template for remembering Canada’s past. Over the past 50 years, this narrative has changed, as curators have employed artefacts and museum environments to construct patriotic pride in their nation. Until 2017, this narrative was blatantly exclusionary of Indigenous voices. More recently, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has called for reconciliation in education, including public forums for education. The Canadian Museum of History has responded to this call by weaving Indigenous voices into the national narrative of the new Canadian History Hall. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Partial Histories: Constituting a Conflict between Women's Equality Rights and Indigenous Sovereignty in Canada Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59c8k7c0 Author Painter, Genevieve Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Partial Histories: Constituting a Conflict between Women's Equality Rights and Indigenous Sovereignty in Canada by Genevieve Painter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge Professor Calvin K. Morrill, Chair Professor Leti P. Volpp Professor Marianne Constable Fall 2015 Abstract Partial Histories: Constituting a Conflict between Women's Equality Rights and Indigenous Sovereignty in Canada by Genevieve Painter Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Calvin K. Morrill, Chair This dissertation is a history of an idea, a retelling of a simple story about an idea as a complicated one, and an explanation of the effects of believing the simple story. From 1869 to 1985, to be an Indian in the eyes of the Canadian state – to be a “status Indian” – a person had to have a status Indian father. The Canadian government registered a population of Indigenous people as status Indians and decided that Indian status passed along the male line. If an Indian man married a non-Indian woman, his wife gained status and their children were status Indians. In contrast, if a status Indian woman married a non-Indian man, she lost her Indian status, and her children were not status Indians. -

Pharmaceutical Policy Reform in Canada: Lessons from History

Health Economics, Policy and Law (2018), 13, 299–322 © Cambridge University Press 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S1744133117000408 Pharmaceutical policy reform in Canada: lessons from history KATHERINE BOOTHE* Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada Abstract: Canada is the only country with a broad public health system that does not include universal, nationwide coverage for pharmaceuticals. This omission causes real hardship to those Canadians who are not well-served by the existing patchwork of limited provincial plans and private insurance. It also represents significant forgone benefits in terms of governments’ ability to negotiate drug prices, make expensive new drugs available to patients on an equitable basis, and provide integrated health services regardless of therapy type or location. This paper examines Canada’s historical failure to adopt universal pharmaceutical insurance on a national basis, with particular emphasis on the role of public and elite ideas about its supposed lack of affordability. This legacy provides novel lessons about the barriers to reform and potential methods for overcoming them. The paper argues that reform is most likely to be successful if it explicitly addresses entrenched ideas about pharmacare’s affordability and its place in the health system. -

The Public Dimension of Broadcasting: Learning from the Canadian Experience

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 294 535 IR 013 080 AUTHOR Raboy, Marc TITLE The Public Dimension of Broadcasting: Learning from the Canadian Experience. PUB DATE Jul 86 NOTE 47p.; Paper presented at the International Television Studies Conference (London, England, July 10-12, 1986). PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Industry; Communications; Community Role; Cultural Influences; Foreign Countries; Government Role; History; *Mass Media; Nationalism; *Political Attitudes; Programing (Broadcast); *Public Service; Television Research IDENTIFIERS *Canada; *Private Sector ABSTRACT The political context surrounding Canadian broadcasting dramatically changed following the election of a conservative government in 1984, and Canada's current broadcasting debate is marked by national and special interest concerns. While an important social aspect of the system is its profoundly undemocratic nature, the constituent elements of a democratic public medium exist. In dealing with the democratization of communications, it is first necessary to clarify the place of communications in democratic public life, then recognize the public character of the media. The Canadian broadcasting experience has contributed its share to obscuring the emancipatory potential of broadcasting, but it also contains the seeds of its own antithesis, and the struggles around it provide many instructive elements of an alternative approach to broadcasting based on a reconstituted public dimension. This public dimension can be fully realized only if a number of critical areas are transformed. From a critical analysis of the Canadian experience and the alternative practices and proposals that have marked it, there emerge some elements of a more coherent, responsive, direct system of public broadcasting. -

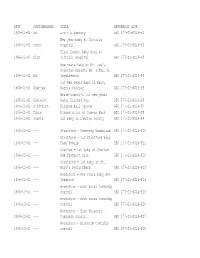

DATE PHOTOGRAPHER TITLE REFERENCE CODE 1966-01-01 Ed. Levee a Armoury AFC 177-S1-SS14-F1 1966-01-01 Chute New Year Baby at Victo

DATE PHOTOGRAPHER TITLE REFERENCE CODE 1966-01-01 Ed. Levee a Armoury AFC 177-S1-SS14-F1 New year baby at Victoria 1966-01-01 Chute Hospital AFC 177-S1-SS14-F2 First London baby born at 1966-01-01 Dick Victoria Hospital AFC 177-S1-SS14-F3 New Years baby at St. Joe's hospital parents Mr. & Mrs. B. 1966-01-01 Ed. Szymkiewicz AFC 177-S1-SS14-F4 1st New Years baby in Kent, 1966-01-01 Chatham Barrie Crozier AFC 177-S1-SS14-F5 Bruce county's 1st new years 1966-01-01 Cantelon baby, Fischer boy AFC 177-S1-SS14-F6 1966-01-01 Stratford Kingdom Hall opened AFC 177-S1-SS14-F7 1966-01-01 Chute Presentation at Queens Park AFC 177-S1-SS14-F8 1966-02-01 Sarnia 1st baby in Lambton county AFC 177-S1-SS14-F9 1966-02-01 --- Stratford - Cemetery Vandalism AFC 177-S1-SS14-F10 Stratford - 1st Stratford baby 1966-02-01 --- Faye Fowlie AFC 177-S1-SS14-F11 Chatham - 1st baby at Chatham 1966-02-01 --- PGH Thompson girl AFC 177-S1-SS14-F12 Stratford - 1st baby at St. 1966-02-01 --- Mary's David Sharp AFC 177-S1-SS14-F13 Woodstock - New Years baby Ann 1966-02-01 --- Crawford AFC 177-S1-SS14-F14 Woodstock - East Zorra township 1966-03-01 --- council AFC 177-S1-SS14-F15 Woodstock - West Zorra township 1966-03-01 --- council AFC 177-S1-SS14-F16 Woodstock - East Nissouri 1966-03-01 --- township council AFC 177-S1-SS14-F17 Woodstock - Blenheim township 1966-03-01 --- council AFC 177-S1-SS14-F18 1966-03-01 --- Chatham council inaugural AFC 177-S1-SS14-F19 Thames Secondary school, 1966-03-01 Lee opening day activities AFC 177-S1-SS14-F20 Sarnia - CIL construction at 1966-03-01 --- Courtright AFC 177-S1-SS14-F21 1966-03-01 --- Sarnia - Old hotel at Sombra AFC 177-S1-SS14-F22 Woodstock - North Oxford 1966-03-01 --- township council AFC 177-S1-SS14-F23 Sarnia - Demolition of salt 1966-03-01 --- plant AFC 177-S1-SS14-F24 St. -

Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War: First

Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War ⁄ Comité Canadien de l' Histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale The first conference ⁄ La première conférence at ⁄ au Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean 20 - 22 Oct 1977 Proceedings Compte rendu CANADIAN COMMITTEE FOR THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR Proceedings of the First Conference Held at Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean Saint-Jean, Quebec 20-22 October, 1977 These proceedings are being distributed with the permission of the authors of the various papers given at our first conference. because of the disparate nature of the subjects it was considered preferable not to seek a publisher for the proceedings, but rather to limit distribution to members of the Canadian Committee and certain other interested people, such as the president and secretary of the international committee. Consequently no attempt has been made to link the papers to an overall theme, and there has not been the rigorous editing that would have accompanied publication. It was a suggestion to hold a conference on the Dieppe landings in 1942 that prompted these meetings. When it was found that there was inadequate interest among historians in Canada for an exhaustive examination of the Dieppe question, or even of a reconsideration of Canadian military operations in the Second World War, we decided to build a conference around the most active research under way in Canada. This meant that there was no theme as such, unless it could be called "The Second World War: Research in Canada Today". Even that would have been inaccurate because there was no way of including all aspects of such research, which is in various stages of development in this country, in one relatively small and intimate conference.