Mystical Transformation in James Hudson Taylor (1832–1905)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Conference Abstracts

ANNUAL CONFERENCE 14-17 April 2014 Arena and Convention Centre, Liverpool ABSTRACTS SGM ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 2014 ABSTRACTS (LI00Mo1210) – SGM Prize Medal Lecture (LI00Tu1210) – Marjory Stephenson Climate Change, Oceans, and Infectious Disease Prize Lecture Dr. Rita R. Colwell Understanding the basis of antibiotic resistance University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA as a platform for early drug discovery During the mid-1980s, satellite sensors were developed to monitor Laura JV Piddock land and oceans for purposes of understanding climate, weather, School of Immunity & Infection and Institute of Microbiology and and vegetation distribution and seasonal variations. Subsequently Infection, University of Birmingham, UK inter-relationships of the environment and infectious diseases Antibiotic resistant bacteria are one of the greatest threats to human were investigated, both qualitatively and quantitatively, with health. Resistance can be mediated by numerous mechanisms documentation of the seasonality of diseases, notably malaria including mutations conferring changes to the genes encoding the and cholera by epidemiologists. The new research revealed a very target proteins as well as RND efflux pumps, which confer innate close interaction of the environment and many other infectious multi-drug resistance (MDR) to bacteria. The production of efflux diseases. With satellite sensors, these relationships were pumps can be increased, usually due to mutations in regulatory quantified and comparatively analyzed. More recent studies of genes, and this confers resistance to antibiotics that are often used epidemic diseases have provided models, both retrospective and to treat infections by Gram negative bacteria. RND MDR efflux prospective, for understanding and predicting disease epidemics, systems not only confer antibiotic resistance, but altered expression notably vector borne diseases. -

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions William D. Taylor, Editor William Carey Library Pasadena, California, USA Editor: William D. Taylor Technical Editor: Susan Peterson Cover Design: Jeff Northway © 1994 World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying and recording, for any purpose, without the express written consent of the publisher. Published by: William Carey Library P.O. Box 40129 Pasadena, CA 91114 USA Telephone: (818) 798-0819 ISBN 0-87808-249-2 Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Preface Michael Griffiths . vii The World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission William D. Taylor . xiii 1 Introduction: Setting the Partnership Stage William D. Taylor . 1 PART ONE: FOUNDATIONS OF PARTNERSHIP 2 Kingdom Partnerships in the 90s: Is There a New Way Forward? Phillip Butler . 9 3 Responding to Butler: Mission in Partnership R. Theodore Srinivasagam . 31 4 Responding to Butler: Reflections From Europe Stanley Davies . 43 PART TWO: CRITICAL ISSUES IN PARTNERSHIPS 5 Cultural Issues in Partnership in Mission Patrick Sookhdeo . 49 6 A North American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Paul McKaughan . 67 7 A Nigerian Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Maikudi Kure . 89 8 A Latin American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Federico Bertuzzi . 93 9 Control in Church/Missions Relationship and Partnership Jun Vencer . 101 10 Confidence Factors: Accountability in Christian Partnerships Alexandre Araujo . 119 iii PART THREE: INTERNATIONALIZING AGENCIES 11 Challenges of Partnership: Interserves History, Positives and Negatives James Tebbe and Robin Thomson . 131 12 Internationalizing Agency Membership as a Model of Partnership Ronald Wiebe . -

Hudson Taylor's Spiritual Secret

Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret FOREWORD This record has been prepared especially for readers unfamiliar with the details of Mr. Hudson Taylor's life. Those who have read the larger biography by the present writers, or Mr. Marshall Broomhall's more recent presentation, will find little that is new in these pages. But there are many, in the western world especially, who have hardly heard of Hudson Taylor, who have little time for reading and might turn away from a book in two volumes, yet who need and long for just the inward joy and power that Hudson Taylor found. The desire of the writers is to make available to busy people the experiences of their beloved father—thankful for the blessing brought to their own lives by what he was, and what he found in God, no less than by his fruitful labors. Howard and Geraldine Taylor Philadelphia, May 21, 1932 Men are God's method. The church is looking for better methods; God is looking for better men. What the church needs today is not more machinery or better, not new organizations or more and novel methods, but men whom the Holy Ghost can use—men of prayer, men mighty in prayer. The Holy Ghost does not come on machinery, but on men. He does not anoint plans, but men—men of prayer . The training of the Twelve was the great, difficult and enduring work of Christ. It is not great talents or great learning or great preachers that God needs, but men great in holiness, great in faith, great in love, great in fidelity, great for God—men always preaching by holy sermons in the pulpit, by holy lives out of it. -

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays ABSTRACT Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. In many ways it is the most striking example of that resurgence. Along with Roman Catholics, as of the 1950s Chinese Protestants carried the heavy historical liability of association with Western domi- nation or imperialism in China, yet they have not only overcome that inheritance but have achieved remarkable growth. Popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. This article first traces the gradual extension of interest in Chinese Protestants from Christian circles to the scholarly world during the last two decades, and then discusses salient characteristics of the Protestant movement today. These include its size and rate of growth, the role of Church–state relations, the continuing foreign legacy in some parts of the Church, the strong flavour of popular religion which suffuses Protestantism today, the discourse of Chinese intellectuals on Christianity, and Protestantism in the context of the rapid economic changes occurring in China, concluding with a perspective from world Christianity. Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. Today, on any given Sunday there are almost certainly more Protestants in church in China than in all of Europe.1 One recent thoughtful scholarly assessment characterizes Protestantism as “flourishing” though also “fractured” (organizationally) and “fragile” (due to limits on the social and cultural role of the Church).2 And popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. -

PROVING GOD Financial Experiences of the China Inland Mission PROVING GOD Financial Experiences of the China Inland Mission

PROVING GOD Financial Experiences of the China Inland Mission PROVING GOD Financial Experiences of the China Inland Mission by PHYLLIS THOMPSON CHIN A INLAND MISSION Overseas Missionary Fellowship London, Philadelphia, Toronto, Melbourne, Thun, Cape Town and Singapore First published 1956 Second edition 1957 Made in Great Britain Published by the China Inland Mission, Newington Green, London, N.16, and printed by The Camelot Press Ltd., London and Southampton Trade Agents: The Lutterworth Press, 4 Bouverie Street,London, E.C.4 CONTENTS CHAP, FOREWORD 7 INTRODUCTION 13 I. A PLOT OF LAND 19 2. HELD BY THE ENEMY 31 3· THE FLEDGLINGS 44 4. "SHALL I NOT SEEK REST FOR THEE?" 57 5· EMERGENCY HEADQ.UARTERS 65 6. RAYENS IN CHINA 73 7. THE PEGGED EXCHANGE 87 8. PLENTY OF SILVER 95 9. MULTIPLIED MONEY 106 10. THE WITHDRAWAL II5 II. PLACES TO LIVE IN 131 FOREWORD oo is utterly trustworthy. His children can have intimate, personal transactions with Him. There is Gno conceivable situation in which it is not safe to trust Him utterly. Such is the thesis of this book. For six decades the apostle of faith of the last century, George Muller, conducted five large orphan homes in dependence on God alone, neither making nor permitting any appeal to man. Thousands of orphans were given home and education and brought to the Saviour. But beneficent as was this ministry, he did not conceive it to be the primary object of these institutions. To him they· provided a unique opportunity of bringing home to a generation to whom He had become remote, the unfailing faithfulness of God. -

The Church of God Mission

In the Summer 2014 issue of Japan Harvest magazine, the official publication of the Japan Evangelical Missionary Association (JEMA), we began publishing profiles of our member missions. This has been an ongoing process, both to assemble profiles of existing members, and gather those of new members. As a result, this current booklet is not in alphabetical order, rather in the order in which profiles were published in our magazine. As you read, please note the publishing date on the bottom of each page, and realize that for some missions their goals and activities may have changed since that time. Although most of our member missions are included in this file, it is not complete. As of this date 2017 JEMA Plenary (February 18, 2017), we have 44 member missions. Current members not represented in this document are: Evangelical Free Church of Canada Mission JEMAInternational Plenary Mission Session Board Roll 2017 The Redeemed Christian Church of God Member Mission Member Count Votes Delegates 1 Act Beyond (formerly Mission to Unreached Peoples) 4 1 - 2 Agape Mission 28 6 NICHOLAS SILLAVAN, Craig Bell 3 Asian Access 28 6 GARY BAUMAN, John Houlette 4 Assemblies of God Missionary Fellowship 35 7 BILL PARIS, Susan Ricketts 5 Christian Reformed Japan Mission 10 2 - 6 Church Missionary Society - Australia 10 2 - 7 Church of God Mission 8 2 - 8 Converge Worldwide Japan 10 2 JOHN MEHN 9 Evangelical Covenant Church 8 2 - 10 Evangelical East Asia Mission 4 1 KERSTIN DELLMING 11 Evangelical Free Church of America ReachGlobal 14 3 - Japan 12 Evangelical -

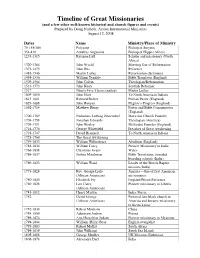

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

China with London Missionary Society Settled in Canton – Learnt Cantonese and Mandarin Became Translator with East India Company (1809)

Robert Morrison (1782-1834) 1807 Missionary to China with London Missionary Society Settled in Canton – Learnt Cantonese and Mandarin Became translator with East India Company (1809). Published the Bible in Chinese: New Testament (1814), Old Testament (1818) Established Anglo-Chinese college at Malacca (1820) Published Dictionary of the Chinese Language (1821) The association with the British East India Company had the detrimental effect of missionaries being looked up on as foreign devils. Robert Morrison died in Canton on August 1, 1834 At the time of Robert Morrison’s death there were only known to be 10 baptized believers in China. By 1842 this number was reduced to six. Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860) Prior to the opium wars merchants smuggled opium from India into China. The sale of opium to China provided a balance of trade for tea. 1839 The first opium war began. China 1856 The second opium war began destroyed opium which had been after a Chinese search of a British confiscated from British ships. registered ship. James Hudson Taylor (1832-1905) Founder: China Inland Mission Took the gospel into the interior of China. Used the principles of George Muller in financing the mission Would not ask for funds but relied upon unsolicited donations Born May 21, 1832. in Barnsley, North Yorkshire, England Not a healthy boy - Learnt at home. 15 years old. He began work as bank clerk but after 9 months quit – eyes became inflamed. 17 years old. Had a conversion experience after reading tract on ‘finished work of Christ’. After conversion he desired to be missionary in China Studied medicine with aim of going to China as a missionary. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY HUDSON TAYLOR AND THE CHINA INLAND MISSION 1. PRIMARY SOURCES: Publications by J.H. Taylor and the CIM 1.1 JAMES HUDSON TAYLOR China’s Spiritual Need and Claims (London: Morgan & Scott, 1865). Brief Account of the Progress of the China Inland Mission from May 1866 – May 1868 (London: Nisbet & Co.1868). The Arrangements of the CIM (Shanghai: CIM, 1886). Union and Communion or Thoughts on the Song of Solomon. (London: Morgan and Scott, 1894). After Thirty Years: Three Decades of the CIM (London: Morgan and Scott, 1895). Hudson Taylor’s Retrospect (London: OMF Books, Eighteenth Edition, 1974). Unfailing Springs (Sevenoaks: Overseas Missionary Fellowship, n.d.). Union and Communion (Ross-shire: Christian Focus, 1996). 1.2 CIM ARCHIVES (Held at THE SCHOOL FOR ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON and at OMF INTERNATIONAL (UK), BOROUGH GREEN, KENT, ENGLAND) JAMES HUDSON TAYLOR’S PAPERS: Section 1 1849 –1874 Boxes 1-3 Section 2 1853 Box 4 Section 3 1854-1856 Box 4 Section 4 1857-1865 Boxes 5 and 6 Section 5 1866-1870 Boxes 6-8 Section 6 1871-1882 Boxes 9 & 10 Section 7 1883-1886 Box 11 Section 8 1887-1890 Boxes 12 & 13 Section 9 1891-1898 Boxes 14 & 15 Section 10 1899-1905 Boxes 16 & 17 Section 11 General Papers Boxes 18-19 CHINA INLAND MISSION 1. LONDON COUNCIL Section 1-48 2. CIM CORPORATION Section 49-68 3. CHINA PAPERS Section 69-92 4. ASSOCIATE MISSIONS Section 93-96 5. PUBLICATIONS Section 97-433 Periodicals: CIM, Occasional Papers, London 1866-1867 CIM, Occasional Papers, London 1867-1868 CIM, Occasional Papers, London 1868-1869 CIM, Occasional Papers, London 1870-1875 CIM, China’s Millions, London 1875 – 1905 CIM Monthly Notes (Shanghai: CIM, 1908-1913) The China Mission Hand-Book (Shanghai: American Presbyterian Press, 1896). -

Collaboration, Christian Mission and Contextualisation: the Overseas Missionary Fellowship in West Malaysia from 1952 to 1977

Collaboration, Christian Mission and Contextualisation: The Overseas Missionary Fellowship in West Malaysia from 1952 to 1977 Allen MCCLYMONT A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Kingston University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Submitted June 2021 ABSTRACT The rise of communism in China began a chain of events which eventually led to the largest influx of Protestant missionaries into Malaya and Singapore in their history. During the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960), a key part of the British Government’s strategy to defeat communist insurgents was the relocation of more than 580,000 predominantly Chinese rural migrants into what became known as the ‘New Villages’. This thesis examines the response of the Overseas Missionary Fellowship (OMF), as a representative of the Protestant missionary enterprise, to an invitation from the Government to serve in the New Villages. It focuses on the period between their arrival in 1952 and 1977, when the majority of missionaries had left the country, and assesses how successful the OMF was in fulfilling its own expectation and those of the Government that invited them. It concludes that in seeking to fulfil Government expectation, residential missionaries were an influential presence, a presence which contributed to the ongoing viability of the New Villages after their establishment and beyond Independence. It challenges the portrayal of Protestant missionaries as cultural imperialists as an outdated paradigm with which to assess their role. By living in the New Villages under the same restrictions as everyone else, missionaries unconsciously became conduits of Western culture and ideas. At the same time, through learning local languages and supporting indigenous agency, they encouraged New Village inhabitants to adapt to Malaysian society, while also retaining their Chinese identity. -

Three Missionary Profiles the Life of Lottie Moon

http://home.snu.edu/~hculbert/ Here’s a “readers’ theatre” look at some missionaries. It can be used in a classroom with or without practice. All you need are some good readers. Three Missionary Profiles These brief plays profile the lives of Lottie Moon, C.T. Studd and the Hudson Taylors. It was originally performed as a single play in three acts. However, it can easily be broken up and performed or read as three separate one-act plays. These portrayals show these missionaries as real people with warts and frailties. It is hoped that people, on seeing these performances, will realize that one need not be a saint to go into global missions work. This play may be performed without charge by any school, church or religious group, provided no more than 5% of its original content is changed. Copyright © 1996 David Prata The Life of Lottie Moon Written by David Prata ANNOUNCER: (offstage) Lottie Moon was born in 1840 in Virginia where she grew up on her family's tobacco plantation. Some have said that a divine calling, an adventuresome spirit and a feminist impulse were the main factors in the nineteenth century that created a surge of single women into world missions. Indeed, those three things -- a sense of calling, adventuresome spirit and a feminist impluse -- were what thrust Lottie Moon into a fruitful life of missionary service. LOTTIE: (Entering from stage left, looking up for the voice of the announcer) Excuse me, but you are leaving a few things out. ANNOUNCER: And who, madam might you be? LOTTIE: I might be your great aunt Minnie, but as it happens, I am Lottie Moon, and I will tell this story myself if you don't mind, sir. -

Lives Worth Imitating – Hudson Taylor September 1, 2019

Lives Worth Imitating – Hudson Taylor September 1, 2019 This morning I want to explore the life of one Hudson Taylor. Most people I have mentioned his name to this past week have never heard of him. Hopefully you won’t be able to say that again after today. Hudson Taylor and the word, China, should always go hand in hand. His mother and father were fascinated with China, although they lived in England. When Hudson’s mother became pregnant, his parents prayed that God would raise him up to be a missionary to the Chinese. And when Hudson was only 4 years old he declared his intent to grow up and do just that. • Hudson Taylor was born on May 21, 1832 to James and Amelia Taylor who were devout Methodists. His father was a chemist and a local Methodist preacher. • Hudson was sold out to God at age 17. (But it came in a dramatic and creative way) When Hudson was 15 years old he started working as a junior clerk at one of the local banks. The fellow employees were quite worldly in their lifestyles and ridiculed Taylor’s views on God, which led him to question his conservative Christian upbringing. Over time, he adopted their perspective and concluded that he could live his life anyway he wanted, because there was no God to whom he must answer. Shortly after that he developed an eye infection which forced him to quit working at the bank and go to work for his father. His father became quite irritated by Taylor’s moodiness, but his mother looked deeper and was concerned with his spiritual condition and began praying for him to return to the Lord.