Sharing Education Without Oppression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TL 16.1.4.Indd

THE TEACHING LIBRARIAN The magazine of the Ontario School Library Association volume 16, number 1 ISSN 1188679X 21st-Century Learning @ your library™ THE TEACHING LIBRARIAN volume 16, number 1 ISSN 1188679X 21st-Century Learning @ your library™ 14 Library Updating Tips Sue Anderson 10 School Libraries People for Education and Gay Stevenson 20 Times are Changing Gillian Hartley 22 How we walk the talk in the library at Stephen Lewis Secondary School in Mississauga Mary-Ann Budak-Gosse 19 19 Food Force Julie Marshall 24 Beyond Reading Aloud Cynthia Graydon 26 Wikis and Blogs for Student Learning – Why Not? Bobbie Henley and Kate McGregor 29 Videoconferencing @ your library Deborah Kitchener 30 ABEL Technology @ your library Rob Baxter 32 Moodle @ Maple HS 34 Nadia Sturino and Themi Drekolias 34 Meet the Author: Vicki Grant Wendy D’Angelo 38 2008 Forest of Reading Festival of Trees – Photo Essay 42 Student Writing Contest Aids the Homeless Anita DiPaolo-Booth 7 The Editor’s Notebook 16 Professional Resources Brenda Dillon 8 President’s Report Lisa Radha Weaver 33 Book Buzz Martha Martin 40 12 The Connected Library Brenda Dillon 36 Drawn to the Form Christopher Butcher 13 School Library Seen Callen Schaub The Teaching Librarian volume 16, no. 1 3 Discover NORTH AMERICA’S #1 Educational Search Engine Trusted by More Than 12 Million Students, Teachers, and Librarians Worldwide. Connect. Educators and students to a wealth of standards- based K-12 online resources, organized by readability and grade level. Protect. Your entire district from inappropriate and irrelevant content, every search, every school day – from school and from home. -

The York Region Board of Education Board

THE YORK REGION BOARD OF EDUCATION BOARD MEETING - PUBLIC SESSION SEPTEMBER 27, 1993 The Board Meeting - Public Session of The York Region Board of Education was held in the Board Room of the Education Centre - Aurora at 8:20 p.m. on Monday, September 27, 1993 with Chair B. Crothers presiding and the following members present; Trustees Barker, Bennett, Bowes, Caine, Dunlop, French, Hackson, Hogg, Irish, Jonsson, Kadis, Krever, Middleton, Nightingale, Pengelly, Sinclair, Stevenson, Wakeling and Wallace. INVOCATION Trustee N. Dunlop opened the meeting with the invocation. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 1. Moved by D. Caine, seconded by R. Wallace: That the Agenda be approved with the changes announced by the Board Chair. - Carried - APPROVAL OF MINUTES 2. Moved by P. Bennett, seconded by J. Jonsson: That the Minutes of the Board Meeting - Public Session, of August 30, 1993 be approved as written. ROUTINE REPORTS 3. Moved by K. Barker, seconded by B. Hogg: That the following routine reports be adopted in accordance with Board procedure. CHAIRS’ COMMITTEE REPORT #9, SEPTEMBER 20, 1993 1) Trustee Conference Registration That the Board approve the following requests for Trustee conference registration. Trustee Conference, Date and Location Expenditure Approval Policy #120.0 L. Pengelly The Canadian Institute Clause 2(a) Violence in Schools Toronto, November 17 & 18, 1993 Board Minutes - Public Session Page 2 September 27, 1993 2) Selection Committee - Superintendent of Employee Services That the following trustees be appointed to the Selection Committee for the Superintendent of Employee Services; B. Crothers, N. Dunlop and H. Krever. 3) Committee to Review Board Structure and Reporting Process That the following trustees be appointed to the Committee to Review the Board Structure and Reporting Process; B. -

Indigenous Peoples' Right to Adequate Housing

Indigenous peoples’ right to adequate housing A global overview United Nations Housing Rights Programme Report No. 7 United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Nairobi, 2005 This publication has been reproduced without formal editing by the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the United Nations, and a failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. Excerpts from the text may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Cover design: Sukhjinder Bassan, UN-HABITAT. Cover photo credits: Miriam Lopez Villegas. Printing: UNON Printshop, Nairobi. UN-HABITAT Nairobi, 2005. HS/734/05E ISBN 92-1-131713-4 (printed version) ISBN 92-1-131522-0 (electronic version) ISBN 92-1-131664-2 (UNHRP report series, printed version) ISBN 92-1-131513-1 (UNHRP report series, electronic version) An electronic version of this publication is available for download from the UN-HABITAT web-site at (http://www.unhabitat.org/unhrp/pub). The electronic version – in compiled HTML format, allowing complex text searches – requires Microsoft Windows 98 or later; or Microsoft Windows 95 plus Microsoft Internet Explorer (version 4 or later). -

Teaching Identities: Lessons from Aujuittuq (The Place That Never Thaws)

CHAPTER 21 Teaching Identities: Lessons from Aujuittuq (The Place That Never Thaws) Heather McLeod and Dale Vanelli Introduction Heather is an arts educator at Memorial University in Newfoundland, Can- ada, and Dale is a writer. We are spouses. In this chapter the everyday life that comes under our scrutiny is our past teaching in Aujuittuq (the place that never thaws), or the hamlet of Grise Fiord, Nunavut, (pop. 150) (cf. McLeod & Vanelli, 2015). Canada’s most northern civilian community on the southern tip of Ellesmere Island, it is 3,460 km north of Ottawa in the High Arctic. Using a duoethnographic approach (Sawyer & Norris, 2013) we examine how this landscape inscribed our bodies, and how we opened both ourselves and the discourses in which we interacted to the possibilities of change; we ask how were our teaching identities constructed in a new landscape and climate (Davies, 2000; Davies & Gannon, 2006)? Aujuittuq and Colonization in the High Arctic In Aujuittuq most inhabitants are Inuit and their first language is Inuktitut. At 76 degrees 25 north latitude, when a compass is pointed due North the nee- dle will point Southwest since it is above the magnetic North Pole. It is too far north to see the Northern Lights. A huge geographical landmass, Ellesmere Island is considered so remote that many maps of Canada omit it altogether. The hamlet is perched at the bottom of a steep glacial mountain on the very edge of Jones Sound and, for much of the year, the frozen sea ice is referred to as the land. The Canadian government created the community in 1953 for two calculated reasons. -

2015-2016 OFSAA Championship Calendar Character Athlete Award

WINTER 2015 CHAMPIONSHIP RESULTS SPRING 2015 The Bulletin 2015-2016 OFSAA Championship Calendar Character Athlete Award Winners New OFSAA Rules and Policies EDUCATION THROUGH SCHOOL SPORT LE SPORT SCOLAIRE UN ENTRAINEMENT POUR LA VIE www.ofsaa.on.ca 1 Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations 3 Concorde Gate, Suite 204 Toronto, Ontario M3C 3N7 Website: www.ofsaa.on.ca Phone: (416) 426-7391 Fax: (416) 426-7317 Email: see below Publications Mail Agreement Number: 40050378 Honorary Patron of OFSAA: The Honourable Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario STAFF Executive Director Doug Gellatly Ext. 4 [email protected] Assistant Director Shamus Bourdon Ext. 3 [email protected] Assistant Director Lexy Fogel Ext. 2 [email protected] Communications Coordinator Devin Gray Ext. 5 [email protected] Office Administrator Beth Hubbard Ext. 1 [email protected] Special Projects Coordinator Peter Morris 905.826.0706 [email protected] Special Projects Coordinator Diana Ranken 416.291.4037 [email protected] Special Projects Coordinator Jim Barbeau 613.967.0404 [email protected] Special Projects Coordinator Brian Riddell 416.904.6796 [email protected] EXECUTIVE COUNCIL President Jim Woolley, Waterloo Region DSB P: 519.570.0003 F: 519.570.5564 [email protected] Past President Lynn Kelman, Banting Memorial HS P: 705.435.6288 F: 705.425.3868 [email protected] Vice President Ian Press, Bayside SS P: 613.966.2922 F: 613.966.4565 [email protected] Metro Region Patty Johnson, CHAT P: 416.636.5984 F: 416.636.5984 [email protected] East -

High School Menactra® Clinic Schedule – 2015

Community and Health Services Department Public Health Branch Regional Municipality of York School Immunization Program High School Menactra® Clinic Schedule – 2015 School Clinic School Phone # Town Date Public High Schools Alexander Mackenzie High School 905-884-0554 Richmond Hill 17-Feb-15 Aurora High School 905-727-3107 Aurora 23-Feb-15 Bayview Secondary School 905-884-4453 Richmond Hill 11-Feb-15 Bill Crothers Secondary School 905-477-8503 Unionville 24-Feb-15 Bur Oak Secondary School 905-202-1234 Markham 23-Feb-15 Dr. G.W. Williams Secondary School 905-727-3131 Aurora 24-Feb-15 Dr. J.M. Denison Secondary School 905-836-0021 Newmarket 10-Feb-15 Emily Carr Secondary School 905-850-5012 Woodbridge 12-Feb-15 Huron Heights Secondary School 905-895-2384 Newmarket 3-Mar-15 Keswick High School 905-476-0933 Keswick 9-Feb-15 King City Secondary School 905-833-5332 King City 11-Feb-15 Langstaff Secondary School 905-889-6266 Richmond Hill 23-Feb-15 Maple High School 905-417-9444 Maple 18-Feb-15 Markham District High School 905-294-1886 Markham 25-Feb-15 Markville Secondary School 905-940-8840 Markham 17-Feb-15 Middlefield Collegiate Institute 905-472-8900 Markham 25-Feb-15 Milliken Mills High School 905-477-0072 Unionville 25-Feb-15 Newmarket High School 905-895-5159 Newmarket 18-Feb-15 Pierre Elliott Trudeau High School 905-887-2216 Markham 2-Mar-15 Richmond Green Secondary School 905-780-7858 Richmond Hill 24-Feb-15 Richmond Hill High School 905-884-2131 Richmond Hill 4-Mar-15 Sir William Mulock Secondary School 905-967-1045 Newmarket 9-Feb-15 -

KANATA Vol.2 Fall 2009

KANATA VOLUME 2 UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF THE INDIGENOUS STUDIES COMMUNITY OF MCGILL 1 KANATA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF THE INDIGENOUS STUDIES COMMUNITY OF MCGILL VOLUME 2 FALL 2009 McGILL UNIVERSITY MONTREAL, QUEBEC 2 Acknowledgements Faculty & Scholarly: Support and Advisors Kathryn Muller, Donna-Lee Smith, Michael Loft, Michael Doxtater, Like Moreau, Marianne Stenbaeck, Luke Moreau, Waneek Horn-Miller, Lynn Fletch- er, Niigenwedom J. Sinclair, Karis Shearer, Keavy Martin, Lisa E. Stevenson, Morning Star, Rob Innes, Deanna Reder, Dean Jane Everett, Dean Christopher Manfredi, Jana Luker, Ronald Niezen Organisational Support McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC); First Peoples House (FPH); Borderless Worlds Volunteers (BWV); McGill University Joint Senate Board Subcommittee on First peoples’ Equity (JSBC-FPE); Anthropology Students Association(ASA); Student Society of McGill University 3 KANATA EXECUTIVE PRESIDENT, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PAMELA FILLION EXECUTIVE BOARD, EDITORIAL BOARD JAMES ROSS Paumalū CASSIDAY CHARLOTTE BURNS ALANNA BOCKUS SARA MARANDA-GAUVIN KRISTIN FILIATRAULT NICOLAS VAN BEEK SCOTT BAKER CASSANDRA PORTER SOPHIA RASHID KAHN CRYSTAL CHAN DESIGN EDITORS JOHN AYMES PAUL COL To submit content to Kanata, contact [email protected] 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword- Editor’s Note Pamela Fillion 6 Guest Editorial Reflections on the Utility of Color & Possibility of Coalitions (or Are White People Evil?) Hayden King, McMaster University 8 McMaster University Pow Wow Photos by Danielle Lorenz 16 Diabetes, the -

NEWMARKET HIGH SCHOOL Theatre Presentations: 6:30 Pm Principal’S Welcome Guidance Presentation About Newmarket High School Transition Team Message

GRADE 8 INFORMATION EVENING & OPEN HOUSE Wed. Dec. 12, 2018 NEWMARKET HIGH SCHOOL Theatre Presentations: 6:30 pm Principal’s Welcome Guidance Presentation About Newmarket High School Transition Team Message Newmarket High School is firmly rooted in its community; as such, NHS builds on a 7:15 pm long-standing tradition, which enables its staff and students to respond effectively to French Immersion Program new demands and challenges brought on by a changing environment. Throughout all presentation changes, the school’s community is aware of the importance of maintaining a warm family atmosphere, which supports the needs of its students. 7:30 pm Gifted Program presentation Newmarket High School addresses the concerns and needs of the whole person through its regular programming, additional supports and co-curricular activities. The school 7:45 pm strives to maintain a positive environment in which cognitive and physical development High Performance Athlete (HPA) Program presentation of its students are promoted in association with an awareness of appropriate values, both moral and societal. School Open House: 7:00 pm—8:30 pm Newmarket High School nurtures a climate for school life in which interpersonal, as well Visit with departments and clubs! as school and community, relationships may grow. The school not only promotes open communication between staff and students, but also fosters the same attitude in its communication with parents and with the community at large. Programs at NHS > French Immersion Program > Gifted Program NEWMARKET HIGH SCHOOL > High Performance Athlete Program > Co-operative Education & Specialist High Skills Major Program - Business sector - Construction sector - Health & Wellness sector >Additional opportunities include - Advanced Placement Courses - Dual Credit Courses 505 Pickering Cres. -

Indigenous Homelessness in Canada

Defnition of Indigenous Homelessness in Canada Jesse A. Thistle About The Defnition’s Design The colour scheme (red, black, white and yellow) and the representation of the colours as the four directions are used on the cover and within this report to embody signifcant meanings that exist within First Nations, Métis and Inuit Indigenous cultures. A central philosophy for many Indigenous Peoples is connectedness. Across Indigenous cultures, the circle serves as a recurring shape that represents interconnectivity, as seen with Indigenous medicine wheels and the Indigenous perspective of “All My Relations.” This is the circle of life. “All My Relations” is represented by the circular placement of the freweed, sweetgrass and mayfowers. It is a phrase that encompasses the view that all things are connected, linked to their families, communities, the lands that they inhabit and the ancestors who came before them. Therefore, all beings—animate and inanimate—are viewed as worthy of respect and care and in possession of a purpose are related. Fireweed is a symbol of Indigenous resistance and perseverance; it is also used as a medicine by many Indigenous cultures across Turtle Island. Its young shoots provide springtime nourishment, its mature stems provide a tough fbre for string and nets, and its fowers produce sweet nectar for bees and other insects. Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) grows virtually everywhere in North America, as does sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata) and so these plants were chosen to represent of all three Indigenous Peoples. Moreover, braided sweetgrass is burned as an incense in various Indigenous ceremonies and can be counted as one of the most sacred medicines of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples on Turtle Island. -

References Cited

This is an excerpt from Aboriginal Policy Research Volume 7, published by Thompson Educational Publishing. Not to be sold or redistributed without permission. References Cited Abbas, Rana F. Windspeaker: We’ve heard it all before� Edmonton: Issue 3, Volume 21, June 2003. Allard, Jean. “The Rebirth of Big Bear’s People: The Treaties: A New Foundation for Status Indian Rights in the 21st Century.” Unpublished manuscript, c. 2000. Allard, Jean. “Big Bear’s Treaty: The Road to Freedom.” Inroads, Issue 11, 2002. Allen, Robert C. “The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755–1830.” Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History 14. Ottawa: Thorne Press Limited, 1975. Allen, Robert S. His Majesty’s Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in the Defence of Canada, 1774– 1815. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1992. Allen, Robert (Aber Dole Associates). The Council at Chenail Ecarté. Prepared for the Treaty Policy and Review Directorate, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1995. Archives of Ontario. F 1027-1-3 North-West Angle Treaty #3. RG 4-32, File 1904, No. 680. Assembly of First Nations. “AFN Press Release.” May 19, 2009 <www.afn.ca/article.asp?id=4518> Backhouse, Constance. “Race Definition Run Amok: ‘Slaying the Dragon of Eskimo Status’ in Re Eskimo, 1939.” Colour Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900–1950. Toronto: UTP, 1999: 18–55. Bankes, N. D. “Forty Years of Canadian Sovereignty Assertion in the Arctic 1947–87.” Arctic 40, 4 (December 1987) 285–291. Barnsley, Paul. Windspeaker: Governance Act dead, for now-Nault. Edmonton: Issue 8, Volume 21, November 2003. -

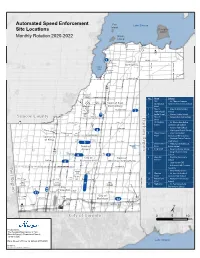

Automated Speed Enforcement Site Locations

Automated Speed Enforcement Fox Lake Simcoe Island Georgina Site Locations Island Monthly Rotation 2020-2022 Snake Island Metro Road North Black River Road Dalton Road Road Kennedy High Baseline Road Street 48 Pefferlaw Road Old Homestead Road Metro Road Old Homestead Road 1South Town of Morton Avenue Georgina Cook's Park RoadPark Bay Glenwoods Avenue Weirs Sideroad Victoria Road The Queensway South Ravenshoe Road Weirs Sideroad 404 Kennedy Road e Queensville Sideroad West Queensville Sideroad No. Road School Ho Woodbine Avenu La lla • 1 Old Street St. Thomas Aquinas n Doane Doane Bathurst R d n o i d Road a n Road Town of East d g Homestead Catholic Elementary School McCowan Road Bradford Street Gwillimbury Road Highway 11 Leslie Street Mount Albert Road 2 Mount • Mount Albert Public 2 Albert Road School Green Lane 2nd Concession Road 3 3 Leslie Street • Sharon Public School West Green Lane East Simcoe County Durham Region 4 Mulock • Newmarket High School Drive s Drive iDav Davis Drive West 5 Wellington • St. Maximilian Kolbe 9 Street Catholic High School Yonge Street Street Prospect • Aurora High School Lloydtown/Aurora Road Mulock Drive Vivian Road • Wellington Public School 4 Lloydtown/Aurora 18th 6 Bloomington • Ecole Secondaire Road Sideroad St Johns Sideroad Warden Avenue Road Catholique Renaissance Township • Cardinal Carter Catholic Wellington Wellington of King Street West Street East Aurora Road High School 5 7 Bloomington • Whitchurch Highlands Musselman Town of Road Public School Lake Aurora 8 King Road • King City Public School 400 • King City Secondary 15th Sideroad Bloomington Road School 6 7 CIty of Town of 9 Bayview • Bayview Secondary King Road Avenue School Bathurst Street Richmond Hill Whitchurch-Stouffville 8 • Jean Vanier CHS • King Vaughan Road Richmond Hill Christian Peel Region Stouffville Road Yonge Street Academy Highway 27 Jane Street Kennedy Road Weston Road • Holy Trinity School Gamble 19th Bayview Avenue Road Avenue 10 Weston • St. -

Resolute Bay

Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community Histories 1950–1975 Resolute Bay Qikiqtani Inuit Association Published by Inhabit Media Inc. www.inhabitmedia.com Inhabit Media Inc. (Iqaluit), P.O. Box 11125, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 1H0 (Toronto), 146A Orchard View Blvd., Toronto, Ontario, M4R 1C3 Design and layout copyright © 2013 Inhabit Media Inc. Text copyright © 2013 Qikiqtani Inuit Association Photography copyright © 2013 Library and Archives Canada, Northwest Territories Archives, and Tim Kalusha Originally published in Qikiqtani Truth Commission: Community Histories 1950–1975 by Qikiqtani Inuit Association, April 2014. ISBN 978-1-927095-62-1 All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law. We acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Book Fund program. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. Please contact QIA for more information: Qikiqtani Inuit Association PO Box 1340, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 Telephone: (867) 975-8400 Toll-free: 1-800-667-2742 Fax: (867) 979-3238 Email: [email protected] Errata Despite best efforts on the part of the author, mistakes happen. The following corrections should be noted when using this report: Administration in Qikiqtaaluk was the responsibility of one or more federal departments prior to 1967 when the Government of the Northwest Territories was became responsible for the provision of almost all direct services. The term “the government” should replace all references to NANR, AANDC, GNWT, DIAND.